CHAPTER 52

Adhesive Capsulitis of the Hip

Definition

Adhesive capsulitis of the hip joint is a condition of unknown etiology characterized by the gradual loss of passive and active hip motion, which is a result of retraction of the fibrous joint capsule.

Lequesne and colleagues [1] classified adhesive capsulitis into primary and secondary forms. Primary adhesive capsulitis is characterized by idiopathic, progressive, painful loss of both active and passive range of motion. Secondary adhesive capsulitis results from known intrinsic or extrinsic causes. Hannafin [2] reported that secondary adhesive capsulitis has a histopathologic appearance similar to that of primary adhesive capsulitis but can be associated with any one of multiple medical conditions (Table 52.1).

Table 52.1

Medical Conditions Associated with Adhesive Capsulitis

Recurrent minor trauma [12,38]

Diabetes mellitus (juvenile and adult onset) [39–41]

Female gender (> 70%) [18]

Age (> 40 years) [38]

Prolonged immobilization of a joint [23]

Coronary artery disease [25]

Autoimmune disorders [17]

After hip surgery

Intra-articular loose bodies

Osteoid osteoma

Synovial chondromatosis

Osteoarthritis

Dupuytren contracture

Elevated C-reactive protein level, positive HLA-B27/serum IgA level

Myocardial infarction

Pulmonary tuberculosis

Bronchitis

Stroke with hemiparesis

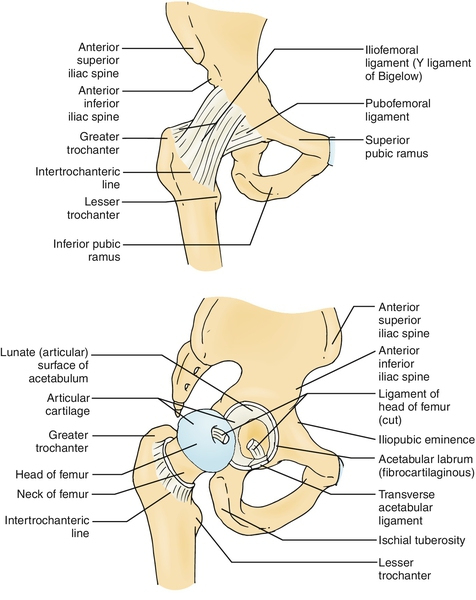

The hip joint is functionally and structurally complex, consisting of the femoral articulation, acetabulum, supporting soft tissue, muscles, and cartilaginous structures (Fig. 52.1). It is a multiaxial synovial ball-and-socket joint [3,4].

The femoral articulation forms roughly two thirds of a sphere, approximately 40% of which is covered by the acetabulum. Articular (hyaline) cartilage covers the femoral articulation except at the fovea capitis, a depression on the central surface.

The acetabulum is formed by fusion of the ilium, ischium, and pubis. It is hemispheric in shape and projects anterolaterally and inferiorly. The lunate surface is the articular portion, and the nonarticular portion constitutes the floor (acetabular fossa). The acetabular fossa (covered by synovium) is continuous with the acetabular notch, which lies between the ends of the lunate surface. The acetabular fossa lies in the inferomedial portion, close to the ligamentum teres (round ligament), which attaches to the fovea capitis. The depth of the acetabulum is increased by the dense fibrocartilaginous labrum, which attaches to the rim of the acetabulum except at the acetabular notch.

The transverse ligament bridges the acetabular notch and in combination with the acetabular labrum forms a complete ring around the acetabulum. It converts the acetabular notch into a foramen through which the intra-articular vessels pass to supply the head of the femur [3,4].

The fibrous capsule of the hip joint attaches to the labrum to form a circular recess, which encloses the joint and most of the femoral neck (Fig. 52.1). Medially, it attaches to the base of the acetabulum and extends to the innominate. Inferiorly, it attaches to the transverse acetabular ligament. Laterally, it attaches to the femur anteriorly and extends along the intertrochanteric line and along the femoral neck posteriorly and inferiorly. The fibrous capsule is reinforced by the pubofemoral, ischiofemoral, and iliofemoral ligaments, which are considered thickening of the fibrous capsule and help to stabilize the hip joint. The capsular fiber consists of both superficial bands and deep bands. The deep circular bands from the iliofemoral ligament form the zona orbicularis, which divides the synovial cavity into medial and lateral recesses. The hip joint is dynamically stabilized by numerous muscles.

Neviaser introduced the term adhesive capsulitis and described pathologic changes in the synovium and subsynovium [5,6]. Evidence supports the hypothesis that the underlying pathologic process involves synovial inflammation with reactive capsular fibrosis, thus making adhesive capsulitis both an inflammatory and a fibrosing condition [2,5–9].

The histologic changes of adhesive capsulitis seen in the hip are similar to those in the shoulder. There is chronic inflammatory reaction in the capsule and synovium with subsequent adherence to the femoral neck [2,8,10,11]. Biopsy tissue shows evidence of edematous, fibrotic synovial tissue with partial or complete loss of synovial lining [2,12].

Many authors acknowledge that adhesive capsulitis is a relatively common clinical syndrome when it occurs in the shoulders (2% to 5% of the general population) but is infrequently described in other joints, such as the wrist, hip, and ankles [2,12–14].

Symptoms

The diagnosis of hip adhesive capsulitis is based on clinical findings of decreased passive and active range of motion in all planes of the hip joint, with no abnormal radiographic findings [5,15]. The patient may describe gradual onset of stiffness with hip movements, resulting in difficulty in crossing the leg or sitting in certain positions. Patients may describe difficulty with lower extremity dressing, such as putting on socks, or with hygiene, such as clipping of toenails.

Pain is usually a presenting symptom, especially with extreme external rotation or abduction, and is usually the reason for seeking medical evaluation. Gait difficulty may or may not be present, but it is usually not to the severity that a gait aid is required.

The diagnosis of hip adhesive capsulitis is rarely made, possibly because the hip joint can sustain range of motion loss without significant disability, whereas even a mild loss of motion in the shoulders can result in significant difficulty with performance of routine activities of daily living [12,13,15].

Physical Examination

Hip pain can be caused by different intra-articular and extra-articular structures. Differentiating the specific pathologic structures can be challenging, but it is critical for appropriate medical management. The history, physical examination, and adjuvant imaging are crucial in identifying the source of pain. In patients with adhesive capsulitis of the hip, the clinical examination findings may be minimal. The patient may or may not exhibit an antalgic gait pattern. The neuromuscular and neurovascular examination findings are usually unremarkable. The back examination is usually benign unless there is a concomitant spinal condition. Provocative maneuvers of the hip joint (i.e., Stinchfield and FABERE tests) may generate nonspecific groin discomfort. The hallmark finding on physical examination is limitation of range of motion of the hip joint in all planes (flexion-extension, internal and external rotation, and abduction-adduction) [16].

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations may differ, depending on the severity of pain and range of motion deficits. Difficulty with activities of daily living are limited to the lower extremities. This can be manifested as difficulty with lower extremity dressing, such as donning or doffing pants, socks, or shoes. There is difficulty in crossing one leg over the other or sitting in a tailor’s position. There may be difficulty in sleeping on one side or the other or standing with the hip externally rotated and abducted. There may be difficulty with prolonged sitting or driving a car, especially if a manual shift is used.

The onset of pain and inflammation causes reflex inhibition of the muscles around the joint, which can subsequently lead to loss of mobility and compensatory abnormal movement of the joint. If gait pattern is affected, recreational and vocational activities that require prolonged ambulation can be affected (i.e., golfing, tennis, or power walking for exercise). With time, there is resolution of pain, but residual range of motion deficits and limitation of function can remain. This persistent loss of mobility and dysfunction can lead to psychosocial issues, such as irritability, depression and anxiety, and disordered sleep patterns.

Diagnostic Studies

Laboratory studies are important in the initial evaluation of intra-articular hip abnormalities. They help assess for autoimmune and rheumatologic conditions. The results of laboratory studies, including blood cell counts, electrolyte values, chemistry panels, acute phase reactants, and rheumatologic screening studies (such as antinuclear antibodies, double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, and HLA-B27 antibodies), are usually normal in patients with adhesive capsulitis of the hip [17,18].

Multiple imaging modalities are available to assess the pelvis and hip joint and surrounding soft tissues. Conventional radiography including anteroposterior views remains the initial imaging modality of choice in assessing patients with groin pain and dysfunction. These studies, however, are of limited value if there is internal derangement as the cause of hip pain because findings are typically normal in those circumstances. In hip adhesive capsulitis, results of these studies are usually normal except for possible diffuse osteopenia, most likely related to pain and decreased range of motion from underlying disease [19]. Griffiths and colleagues [12] reported on a series of patients who had adhesive capsulitis of the hips related to mild trauma or repetitive activity. In all of the patients, the conventional radiographs were unremarkable.

Bone scans can show increased uptake in the areas of osteopenia, but this is usually nonspecific. Focal accumulation of radionuclide reflects an alteration of balanced bone turnover due to changes in bone blood flow and can occur in several conditions [20].

Ultrasonography of the hip has been widely accepted as a useful diagnostic tool in patients with hip pain or limited range of motion. It allows evaluation of different anatomic and pathologic structures, such as joint recess, bursa, tendons, and muscles. It also allows evaluation of the osseous structures of the joint, ischial tuberosity, and greater trochanter. It is useful for guided procedures in the hip joint and periarticular soft tissue under direct visualization.

Ultrasonography has considerable advantages over computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); these include absence of radiation, good visualization of the joint cavity, quantification of soft tissue abnormalities, multiple joint scanning, and rapid side-to-side anatomic comparison. It also has relatively low cost, good patient compliance, and dynamic real-time study of multiple planes. Direct contact with the patient allows maneuvers that elicit symptoms to be evaluated while the study is being performed. Direct ultrasonographic visualization offers the possibility of guided procedures in the hip joint and periarticular soft tissues. The limited size and number of acoustic windows make detailed examination of some structures extremely difficult (i.e., femoral cartilage and hip capsule) [21]. It is not recommended for evaluation of hip adhesive capsulitis, in which there is retraction of the fibrous joint capsule with little or no fluid in the synovial space.

Supplemental imaging with CT or MRI is often used to further evaluate the pelvis and hip to rule out the presence of simple, nondisplaced avulsion to complex fractures and to assess for displacement, comminution, and locations of fragments. MRI is helpful in diagnosis of occult injuries and stress fractures and in the evaluation of the soft tissue and musculature of the pelvis and hip [19,22]. In adhesive capsulitis, CT scans are usually unremarkable and MRI shows capsular thickening with little or no fluid in the synovial space. If the clinical examination or a nonarthrographic CT or MRI study suggests a possible labral or intra-articular hip disease, direct magnetic resonance arthrography is performed [4,23].

Computed tomographic or magnetic resonance arthrography is the preferred examination for evaluation of the joint capsule, labrum, and articular cartilage. Intra-articular needle placement is confirmed under fluoroscopic guidance before 15 mL of 1:200 dilution of a gadolinium contrast agent and normal saline is injected into the joint [4]. Characteristic arthroscopic findings show a hip joint with low volume and loss of normal recesses, high intracapsular pressure, and a thick capsule (Figs. 52.2 and 52.3). There is usually reduction of intra-articular capacity of at least one third (< 10 mL). In the series reported by Griffiths, the patients who underwent arthrography all had small-volume joint space (< 8 mm) with a thick capsule and increased intra-articular pressure. Cone and associates [24] prospectively monitored intracapsular pressure during arthrographic evaluation of 10 patients with a painful hip prosthesis and radiographic evidence of loosening. Fifty percent of patients had restriction of the intra-articular space around the neck of the femoral component during arthroscopy. The contrast agent exhibited irregular appearance related to fibrosis and scarring of the capsule consistent with adhesive capsulitis. In those patients in whom an arthrographic abnormality was demonstrated, the intra-articular pressure was three times greater than normal.

Lequesne described seven patients with pain and limitation of movement in the hip, which he called idiopathic capsular constriction of the hip [1]. Plain radiographs were unremarkable, but hip arthrography suggested diminished articular volume. There was absence of filling of the normal recesses, and the joint had a smaller capacity (< 10 mL) than a normal joint (14-20 mL) [12]. It has been said that if an experienced radiologist has difficulty entering the hip joint, adhesive capsulitis is often the cause [25].

Treatment

Treatment of adhesive capsulitis of the hip is controversial. There are many studies, in both the rheumatologic and orthopedic literature, regarding treatment of the shoulder, but not much is written about treatment of the hips. Neviaser [6–9] and Hannafin [2] have stressed the importance of an individualized program in the treatment of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder based on the understanding of the clinical stages of the disease. The same should apply to the treatment of the hip. However, the diagnosis of hip capsulitis is rarely made, and when it is made, it is usually in the latter stages of the disease based on the time interval. It is exceedingly difficult to accurately quantify stages of the disease in the hip and therefore to correlate a treatment plan based on those stages.

Conservative treatment is recommended as the disease is self-limited. Spontaneous recovery time on average is approximately 13 months, with a range of 5 to 18 months [1,13,26,27]. Chard and Jenner [13] described three middle-aged patients with pain and stiffness in the hips. No evidence of systemic disease, local infection, or lumbar spine disease was found. Bone scan indicated increased uptake in two patients, but the results of hip arthrography and laboratory studies were normal. The patients recovered spontaneously after a few months.

Initial

Pain control can be achieved early with use of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug or oral steroid. If this is not beneficial, an analgesic can be tried. Activity modification is recommended to prevent irritation of the involved extremity. Physical modalities, such as ice massage, superficial moist heat, transcutaneous nerve stimulation, interferential current therapy, and ultrasound, can be applied to help with pain control, swelling, and facilitation of physical therapy.

Rehabilitation

Physical therapy is the treatment of choice. The goal of treatment is primarily to restore mobility. Passive mobilization techniques are used to restore the optimal joint kinematics. These techniques can involve lateral translation, distraction, and anteroposterior glide. These maneuvers are done with the patient lying supine; the proximal thigh is palpated while the distal leg rests over the therapist’s shoulder. The hip joint is distracted by the application of various forces parallel to the neck of the femur. Initially, the mobilization techniques should be gentle, keeping within the range of pain and reactive muscle spasm. The intensity of the exercises can be adjusted according to the irritability of the joint. Ultimately, stronger passive mobilization techniques may be required in which the joint is taken strongly and specifically to the physiologic limit of range to restore the full function of the hip joint. Stretching of the muscles around the hip joint, which tend to shorten, is important. Active mobilization techniques can be used to restore the optimal length of the erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, hamstrings, rectus femoris, iliopsoas, tensor fascia lata, hip adductors, piriformis, and deep external rotators of the hip. Strengthening of the core muscles, gluteals, and hip groups should be done to address strength, endurance, and timing of recruitment of those muscle groups. Miller and coworkers [28] reviewed the cases of 50 patients in a 10-year period and found that the majority of the patients regained motion with minimal residual deficits after conservative treatment with physical therapy and oral medications. In contrast, Shaffer and colleagues [29] reported that 50% of patients had pain or residual stiffness at 7 years after treatment. A specific home exercise program should be included with continued range of motion and flexibility exercises to prevent recurrence of hip adhesive capsulitis.

Procedures

Trigger point injection and intra-articular injection can be tried in recalcitrant cases not responding to conservative treatment. Trigger point injection can be helpful if there is associated muscle pain and spasm. Ultrasound-guided intra-articular injection with long-acting local anesthetic and corticosteroid has been used for pain control. Several randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials have shown improvement of pain and hip disability after intra-articular injection of corticosteroids [30]. Fluoroscopically guided hip injection with contrast material to confirm intra-articular needle placement has been tried; alternatively, the hip joint can be injected during computed tomographic or magnetic resonance arthroscopy.

Manipulation under anesthesia is widely used for adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder but is rarely used in treatment of hip adhesive capsulitis. Luukkainen and associates [31] reported the case of a man with adhesive capsulitis of the hip treated successfully with manipulation under anesthesia and pressure dilation of the joint space by use of isotonic sodium chloride. The patient failed to respond to physical therapy, pharmacotherapy, and intra-articular hip injection with triamcinolone and lidocaine during a period of 3 years.

Surgical intervention may be deemed appropriate if conservative treatment fails and the symptoms persist for more than 15 months with interference of activities of daily living. Arthroscopic release is rarely performed. Mont and colleagues [27] described a patient with adhesive capsulitis who failed to respond to conservative treatment with oral medications, physical therapy, and injection trials. The patient underwent hip capsulectomy through an anterolateral approach 1 year after initial presentation. Continuous passive motion was used during the early postoperative period to maintain range of motion. The anterior approach was used to preserve femoral head vascularity and to limit postoperative bleeding.

Potential Disease Complications

Disease complications are usually related to the range of motion deficits and associated pain that accompanies hip adhesive capsulitis. Functional limitations, which vary from patient to patient, may develop. The loss of mobility at the hip joint can result in difficulties with prolonged stance, ambulation, and sitting. Sleeping postures can also be affected as the patient may not be able to sleep on either side.

Potential Treatment Complications

Pharmacotherapy can lead to treatment complications. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-documented side effects related to the gastrointestinal and renal systems. Oral steroids, if they are used at high doses for a prolonged time, can have systemic effects, such as easy bruising, weight gain, and osteoporosis. The pharmacotherapy complications can be minimized by closely observing the patient’s ongoing medical issues, medication use, and response and potential for drug interactions.

Local injections can cause allergic reactions, infection at the injection site, hematoma, nerve damage, or tendon rupture with inadvertent injection into a nerve or tendon. Physical therapy can result in increased pain and dysfunction if it is not supervised by a well-trained, board-certified physical therapist. Manipulation under anesthesia can lead to an increased risk for chondrolysis and vascular and neurologic insult. Surgical complications are numerous and can include excessive blood loss and postsurgical infection. Compromise of the vascular supply to the femoral head can lead to avascular necrosis and the need for additional surgical procedures. Surgery can result in a cosmetically unpleasant incision around the hip.