CHAPTER 51

Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

Zacharia Isaac, MD; Richard Feeney, DO

Definition

Although chronic low back pain is more commonly attributed to the lumbar intervertebral disc and the zygapophyseal joints, the sacroiliac joint remains a significant cause of low back and buttock pain. However, diagnosis and treatment of sacroiliac joint dysfunction are a clinical challenge. The diagnosis of sacroiliac dysfunction should be considered only after careful exclusion of many separate distinct pathologic entities. Sacral fractures, sacroiliac joint inflammation (such as is seen with various seronegative spondyloarthropathies), metastatic disease, and even infectious seeding of the sacroiliac joint are but a few known pathologic conditions that deserve investigation. Imaging studies are often unhelpful and nonspecific in sacroiliac joint dysfunction. In addition, because of its redundant and variable innervation, sacroiliac joint dysfunction can be manifested with a variable pain referral pattern [1]. Thus, one must consider pathologic changes of neighboring structures sharing pain referral regions with the sacroiliac joint before deciding on the diagnosis of sacroiliac joint dysfunction.

The prevalence of sacroiliac joint dysfunction in those with low back pain complaints is thought to be between 10% and 25%, although during pregnancy the sacroiliac joint is the source of low back or posterior pelvic pain in 20% to 80% of cases [2]. As such, sacroiliac joint dysfunction may be more common in women than in men, and various studies demonstrate a female-to-male ratio of approximately 3:1 to 4:1 [1,3,4]. Moreover, in comparing causes of chronic low back pain, female gender and low body mass index are associated with sacroiliac joint dysfunction [5].

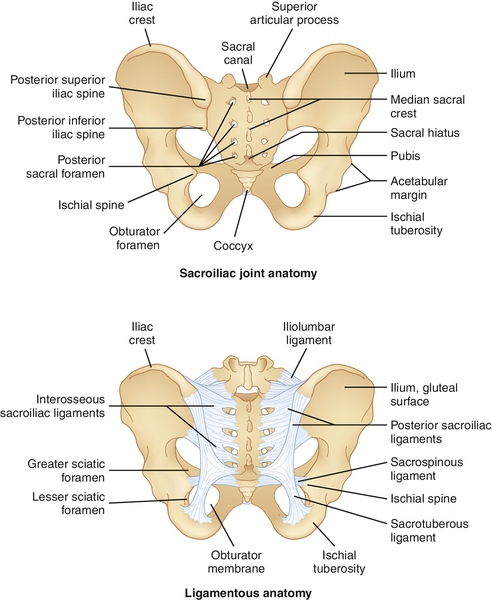

Adjoining the axial and appendicular skeleton, the sacroiliac joint occupies a critical biomechanical position (Fig. 51.1). It is thought that joint dysfunction occurs with structural change to the joint or positional changes relative to the sacrum and pelvis [6]. One can appreciate such changes in pregnancy-related instability [7] or with joint misalignment in adolescents, both of which are known sources of sacroiliac joint pain and dysfunction [8]. Pain associated with changes in position or the joint anatomy itself may be mediated by intra-articular, capsular, and ligamentous structures.

The sacroiliac joints are the bilateral weight-bearing joints that connect the articular surface of the sacrum with the ilium. The anterior and inferior third of the joint is synovial; the remainder of the joint space is syndesmotic. The sacroiliac joint is bordered on its ventral and superior edges by the ventral sacroiliac ligament and on its dorsal and inferior surfaces by the interosseous and dorsal sacroiliac ligaments. The articular capsule of the sacroiliac joint is thin and stabilized anteriorly by the ventral sacroiliac ligament. The strong extracapsular fibers of the dorsal sacroiliac and interosseous ligaments contribute principally to the stability of the joint. Further anchoring of the sacroiliac joint is conferred by the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments, which provide additional connections between the pelvis and sacrum. Innervation of the sacroiliac joint remains an area of active study, and differing descriptions of sacroiliac joint innervation exist. Anatomic studies have described innervation primarily through dorsal rami of spinal nerve roots L5-S4. However, recent studies indicate that the sacroiliac joint receives its innervation from the ventral rami of L4 and L5, the superior gluteal nerve, and the dorsal rami of L5, S1, and S2 or that it is almost exclusively derived from the sacral dorsal rami [9]. Yet others suggest that dorsal innervation to the sacroiliac joint is from the L5 dorsal ramus and the S1-S3 lateral branches, whereas the ventral innervation derives from the ventral rami of L4 and L5 [10].

The sacroiliac joint undergoes changes throughout life that affect the biomechanics of the joint. During childhood and adolescence, the joint is more mobile, absorbing forces throughout the gait cycle. With normal aging, the joints develop uneven opposing surfaces, and the joints are thought to gradually fuse in later years [11]. Movements around the sacroiliac joints are small in magnitude yet complex in nature. As body weight is transmitted downward through the first sacral vertebra, the sacrum is pushed downward and forward, causing its lower end to rotate upward and backward. Although there are no muscles that directly control movements around the joint, imbalance of the musculature surrounding the sacroiliac joint can affect stresses through the joint. Muscles anterior to the sacroiliac joint, including the psoas and iliacus, can influence movement of the sacrum [12]. Weakness in posterior muscles, such as the gluteus maximus and medius, can affect pelvic posture during weight bearing, thereby altering stresses through the joint.

Symptoms

By far the most common presenting symptom of sacroiliac joint dysfunction is low back and gluteal pain, which can be indolent and refractory to traditional interventions and therapies. Pain referral from sacroiliac joint dysfunction is not limited to the lumbosacral region or buttocks, however. Presenting complaints often include pain that is aggravated by prolonged standing, asymmetric weight bearing, or stair climbing. Pain can also stem from running, large strides, or extreme postures [13]. Because of the complex and extensive innervation of the sacroiliac joint as detailed before, dysfunction within the joint may be manifested with pain localizing to several rather removed regions, such as the thigh, groin, and leg. Sacroiliac joint dysfunction does not cause pain by neural compression. However, because of the anatomic proximity of spinal nerve roots to the lumbar and sacral plexuses, pain referral patterns can mimic a variety of neurologic pathologic processes. In a retrospective study of 50 patients with positive diagnostic response to fluoroscopically guided sacroiliac joint injection, investigators sought to characterize the most common presenting symptoms experienced by the cohort. The most common symptoms were buttock pain (94%), lower lumbar pain (72%), and lower extremity pain (50%). Pain in the distal leg and pain in the foot were also reported, as was low abdominal pain and groin pain [1]. Interestingly, the sacroiliac joint is recognized as the most likely source of low back pain after lumbar fusion [14].

Physical Examination

A thorough assessment of the low back, hips, and pelvis, including musculoskeletal and neurologic testing, is essential in isolating back pain caused by sacroiliac joint dysfunction and to exclude other common diagnoses. Examination should include measurement of leg length and assessment of pelvic symmetry by inspection of the posterior superior iliac spine, anterior superior iliac spine, gluteal folds, pubic tubercles, ischial tuberosities, and medial malleoli. The sacral sulcus is palpated and inspected with the patient prone, and any muscle atrophy in the gluteal muscles or distal extremity is noted. Atrophy in the limb implicates a lumbar radiculopathy more than sacroiliac joint syndrome. Palpation of the bony sacrum, subcutaneous tissues, muscles, and ligaments also helps to complete the examination.

Provocative tests have long been used by clinicians to differentiate sacroiliac joint–derived back pain from other regional pain generators. However, repeated clinical studies have suggested that when they are considered separately, the most commonly used provocative tests have low specificity for sacroiliac dysfunction [15–18]. One possible explanation for this is poor inter-rater reliability. Others suggest that both the minimal range of motion around the joints and the difficulty in simulating physiologic stresses through the joints make it more likely that provocative tests will elicit pain from surrounding structures [13]. Such structures include the lumbar intervertebral disc, zygapophyseal joint, and hip joint. Several investigators have shown that in the diagnosis of sacroiliac joint disease, a multitest regimen is more clinically useful than any isolated finding. Recent research suggests that three or more positive findings on provocative tests are 82% to 85% sensitive and 57% to 79% specific for sacroiliac joint disease [18,19]. There is some evidence, in fact, that patients with low back pain who point to the posterior superior iliac spine or within 2 cm from this landmark are more likely to respond to periarticular sacroiliac joint blockade, thus making the patient’s ability to pinpoint the pain a potentially useful tool.

Provocative Tests

Gaenslen Test

With the patient supine, lying close to the edge of the examination table with the buttock of the tested side over the edge of the table, the patient’s leg is dropped off the table such that the thigh and hip are in hyperextension. The contralateral knee is then maximally flexed. Pain or discomfort with this maneuver suggests sacroiliac joint disease, although a false-positive result can be seen in patients with an L2-L4 nerve root lesion [20], spondylolisthesis, sacral fractures, lumbar compression fractures, or spinal stenosis (Fig. 51.2).

Patrick Test (also called FABER Test)

With the patient supine on a level surface, the thigh is flexed and the ankle placed above the patella of the opposite extended leg. Downward pressure is applied simultaneously to the flexed knee and the opposite anterior superior iliac spine as the ankle maintains its position above the knee. Pain or discomfort in the gluteal region reflects sacroiliac disease; pain in the groin or thigh may be suggestive of hip disease (Fig. 51.3).

Gillet Test

With the patient standing, the examiner palpates both the spinous process of the second sacral vertebra and the posterior superior iliac spine of the affected side. The patient is asked to maximally flex the hip on the involved side. A positive test result is indicated by a reproduction of pain and the failure of the palpated posterior superior iliac spine to move inferiorly in relation to the second sacral vertebra [2].

POSH Test (Posterior Shear Test)

With the patient supine, the examiner flexes the hip of the involved side to 90 degrees and adducts the thigh toward midline, providing axial pressure along the femur, directed into the table. This maneuver produces a shear force across the sacroiliac joint and reproduces pain in a symptomatic patient [2].

REAB Test (Resisted Abduction)

With the patient supine, the hip of the involved side is placed in 30 degrees of abduction with the knee extended. The patient is asked to provide an isometric abduction contraction while the examiner resists at the lateral ankle. Reproduction of pain in the region of the sacroiliac joint is a positive test result. The test is thought to stress the cephalad aspect of the joint [2].

Distraction Test (also called the Gapping Test)

With the patient supine, pressure is applied downward and laterally to the bilateral anterior superior iliac spines. This maneuver stretches the ventral sacroiliac ligaments and joint capsule while placing pressure on the dorsal sacroiliac ligaments.

Compression Test

With the patient lying in the lateral recumbent position, the examiner stands behind the patient and applies pressure downward on the uppermost iliac crest, compressing the pelvis. This stretches the dorsal sacroiliac ligaments and compresses the ventral sacroiliac ligaments.

Yeoman Test

With the patient positioned prone, the knee is flexed to approximately 90 degrees and the hip is extended by the examiner. The sacroiliac joint ipsilateral to the extended hip is being tested. Reproduction of familiar gluteal or pelvic pain is considered a positive test result (Fig. 51.4).

Pressure over the Sacral Sulcus

Application of pressure to the gluteal region causing familiar gluteal pain can be suggestive of sacroiliac joint dysfunction. This is commonly seen and is a nonspecific finding; it is often seen in discogenic axial pain, radicular pain, sacral fractures, facet syndrome, and piriformis syndrome.

Active Straight-Leg Raise

While lying supine, the patient lifts the lower extremity, one at a time with the knee extended, approximately 20 cm above the horizontal surface. Pain over the posterior pelvic girdle on either side represents a positive test result suggestive of sacroiliac joint dysfunction. This test has been validated against a prior test of posterior pelvic pain after pregnancy, in which excessive motion at the sacroiliac joint is thought to play a role [21].

Functional Limitations

Patients with sacroiliac joint dysfunction can have a range of functional limitations. There can often be difficulty with sitting, standing, walking, lying, bending, lifting, or sustaining any one position. Thus, their ability to work certain jobs will be limited. These functional limitations can be mild or incapacitating. Known sequelae of chronic pain conditions, including sacroiliac joint dysfunction, are insomnia, depression, globalization of pain syndrome, psychological pain behavior, and symptom magnification. These sequelae can have additional or disproportionate associated functional limitations.

Diagnostic Studies

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction has no valid or reliable diagnostic imaging studies. The purpose of obtaining imaging is to evaluate for alternative diagnoses. Plain radiography can reveal osteologic causes of sacroiliac joint–mediated pain, such as infection and inflammatory or degenerative arthritis. Plain radiographic views, including Ferguson views and anteroposterior views, can help identify sacroiliac joint erosions. Bone scan and computed tomography can detect bone changes caused by entities such as fracture, infection, tumor, sacroiliac joint erosions, and arthritis. Magnetic resonance imaging can reveal these entities as well as show soft tissue disease and marrow changes in sacroiliitis with its associated erosions. Recently, ultrasound has emerged as a modality capable of not only detecting pathologic changes within posterior ligamentous structures of the sacroiliac joint but also providing guidance for accurate intra-articular needle placement for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes [22]. However, true sacroiliac joint dysfunction can often be seen in the presence of normal imaging, and thus it is often defined clinically.

Fluoroscopically guided diagnostic intra-articular injection of anesthetics is considered by some the “gold standard” for diagnosis of sacroiliac joint–derived low back pain [4,17,23,24]. However, numerous investigators have shown anesthetic leakage from the joint space after injection, and there is speculation that overlap to adjacent neural structures may yield erroneous diagnoses of sacroiliac dysfunction. A placebo effect and other nonspecific factors also can lead to improper diagnosis. For these reasons, confirmatory studies should be performed after informed consent has been obtained and the patient is educated about the reasons for confirmatory studies. These confirmatory studies include a patient-blinded, placebo versus anesthetic injection and a variable-duration anesthetic time-dependent block. Despite these measures, reviews of the American Pain Society guidelines suggest that there is only fair to poor evidence for sacroiliac joint blocks to diagnose sacroiliac joint pain [25]. Recent evidence suggests that extracapsular structures, the dense ligamentous network comprising the sacroiliac joint complex, may be a principal cause of persistent pain. In a 2009 study by Dreyfuss and coworkers [10], anesthetic injections performed on asymptomatic individuals provided a strong case for comparative, multisite, multidepth lateral branch blocks as a diagnostic tool before radiofrequency neurotomy, a promising technique for refractory sacroiliac joint pain.

Treatment

Initial

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction is treated initially with relative rest and avoidance of provocative activities. Local modalities, such as ice and heat, or topical analgesics, such as lidocaine in patch form, can be applied for symptomatic relief. Manipulative therapy can alleviate pain and help with muscle spasms but does not change joint alignment significantly. Approximately only 2 degrees of rotation and 0.77 mm of translation occur with stress or manipulation [26,27]. Despite this, there is some evidence that the combination of high-velocity low-amplitude manipulation to both the sacroiliac joint and lumbar spine may provide improvements in pain and functional disability 1 month after intervention for those with sacroiliac dysfunction [28].

Commonly used pharmacologic interventions include acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and muscle relaxants. Chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided because of gastric, renal, and possibly cardiac side effects. Opiates in rare instances can be considered for short-term use but carry potential risks of sedation, constipation, physical dependence, and addiction. Patients with true sacroiliitis related to a seronegative spondyloarthropathy may be candidates for the use of biologic tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor drugs or other disease-modifying agents.

Rehabilitation

Physical therapy is directed toward lumbar core muscle strength and hip girdle flexibility. Modalities such as ice massage, heat, electrical stimulation for the alleviation of pain or muscle spasm, sacroiliac joint mobilization techniques, and postural education exercises may be employed. Sacroiliac joint belts can be helpful and are worth an initial trial to address symptoms. Addressing hip girdle muscle strength, hip range of motion, tight iliotibial band, hip or knee osteoarthritis, trochanteric bursitis, leg length discrepancy, or pelvic obliquity can have adjunctive benefit. Given that most patients undergo rehabilitation for their low back pain without a specific diagnosis, it is difficult to determine whether physical therapy outcomes for sacroiliac joint dysfunction are any more or less effective than for other causes of low back pain. It stands to reason that exercise therapy aimed at improving strength, range of motion, and cardiovascular endurance can only benefit the patient overall and prevent the inherent trend toward deconditioning and activity avoidance behavior.

Procedures

Fluoroscopically guided intra-articular steroid injection can have therapeutic benefit. One study has suggested that up to two thirds of patients with sacroiliac joint dysfunction may attain significant pain relief [29], although the American Pain Society still regards the current evidence behind this therapy as poor [30]. Whenever possible, injection therapy should be complemented with a therapeutic exercise regimen.

Radiofrequency neurotomy has also been described as an effective treatment of sacroiliac joint dysfunction [31]. Interest and study have grown tremendously in this area of late. A recent meta-analysis endorses radiofrequency ablation as beneficial for sacroiliac joint pain for up to 6 months [32]. It is generally accepted that cooled rather than conventional or pulsed radiofrequency ablation is more effective at achieving pain relief [33,34]. Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that multisite, multidepth lateral branch blocks are physiologically effective at a rate of 70%, making this a valuable technique in diagnosis and in deciding to proceed with radiofrequency ablation to manage extra-articular sacroiliac joint pain [10].

Neuromodulatory therapies with an electrical stimulator implanted at the third sacral nerve root in a limited number of subjects with sacroiliac joint pain have also been effective in the management of refractory cases [35]. Prolotherapy has also been described for the treatment of sacroiliac joint dysfunction [16]. Well-designed randomized controlled trials are lacking for nearly all sacroiliac joint dysfunction treatments.

Surgery

Surgery is very rarely performed for sacroiliac joint dysfunction. A thorough workup is required before surgery with minimally invasive diagnostic anesthetization of the sacroiliac joint and to exclude discogenic, facet, radicular, and hip-mediated pain. Surgical intervention involves fusion of the sacroiliac joint with hardware.

Potential Disease Complications

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction, like other causes of chronic pain, can produce pain-related insomnia, depression, anxiety, globalization of pain, and disability. Older patients with gluteal pain should be evaluated for fracture or tumor, and younger patients should be evaluated for seronegative spondyloarthropathy. Degenerative causes of sacroiliac pain are more prevalent in women, whereas inflammatory causes predominate in men.

Potential Treatment Complications

Pharmacologic measures can have numerous side effects. Acetaminophen can be hepatotoxic in large doses. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy is well known to be associated with gastrointestinal and renal side effects along with increased cardiac risk. Manipulation therapy or therapeutic exercise can increase pain in some patients. Intra-articular steroid injection can be associated with temporary increase in pain and local bleeding. Potential systemic steroid effects include increase in serum blood glucose concentration, hypertension, psychosis, and fluid retention. Local steroid injection can cause fatty atrophy, potential infection, and skin depigmentation.