CHAPTER 5 Integrative Neuromuscular Acupoint System

INTRODUCTION

The INMAS protocol resonates with the Western practitioner, thus facilitating its incorporation into pain management. Mechanisms of acupuncture are clarified in terms of their peripheral and central effects (see Chapters 3 and 4) and are explained using basic neuroscientific terminology and concepts that are based on the scientific and clinical discoveries of the last 40 years.

THREE TYPES OF ACUPOINTS

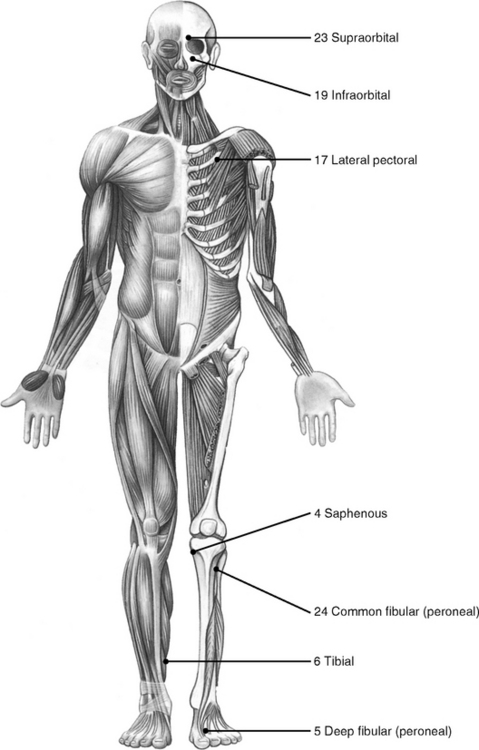

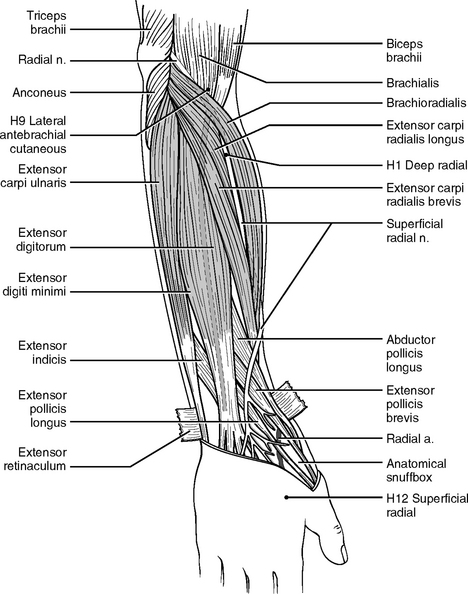

A chronic pathological condition can gradually result in more than 100 tender HAs in the body. Usually other tender HAs develop around what are known as the 24 primary HAs that appear first in the body. For instance, the H1 deep radial acupoint (Figure 5-1) is tender in almost everyone. If homeostasis declines or if an elbow or arm is injured, more tender acupoints appear along the deep radial nerve from H1 distally toward the wrist. Thus, the practitioner need only remember the 24 primary HAs to know all other potential HAs.

The combination of the three types of acupoints forms a universally standardized protocol for all pain symptoms; at the same time this protocol ensures an individualized approach, as is practiced in TCM, by identifying and treating the specific SAs of each patient. In other words, when treating patients, primary HAs are the same for every patient, whereas SAs are individualized symptomatic points. Different SAs require different PAs according to their neurosegmental connection. Thus this protocol contains both standardization and individualization.

The following example explains how we can use one principal protocol to treat two different pain symptoms, elbow pain and knee pain. More detailed instruction is provided in Chapter 6.

| Patient A (with elbow pain) | Patient B (with knee pain) | |

|---|---|---|

| HAs | Primary HAs | Primary HAs (same as patient A) |

| SAs | Locate SAs in elbow and arm | Locate SAs in the knee, thigh, and leg |

| PAs | Use PAs along C4-T1 | Use PAs along L2-5 |

THE RANDOM AND PREDICTABLE PATTERNS OF TENDER ACUPOINT FORMATION

All acupoints consist of peripheral nerve fibers, including the sensory and postganglionic nerve fibers and other soft tissues (see Chapter 1). Acupoints become tender in two distinguishing patterns: the random pattern of SAs and the predictable pattern of HAs.

As previously explained, when homeostasis declines, homeostatic acupoints are gradually transformed from a latent phase (nonsensitive) to passive or active phases. In general, HAs appear symmetrically in predictable locations and predictable sequential order in the human body, and this is referred to as the predictable pattern of tender HA formation. There can be more than 100 HAs in some patients; the first 24 HAs are shown in Figure 5-1. All other HAs appear around these 24 primary HAs, as discussed previously.

The three pathophysiologic phases of acupoints reveal the quantitative and qualitative dynamics of an acupoint: when pathologic factors persist, the number, size, and sensitivity of tender HAs and SAs increase. With proper treatment, the number of tender acupoints decreases and the sensitivity of each acupoint subsides (see Chapters 2 and 3). In the absence of proper treatment or when the self-healing potential is impaired, the size of an acupoint will increase and it will finally become a permanent pathologic structure such as a palpable nodule in the muscle.

There are no “sham” acupoints (see Chapter 4). Stimulated by acupuncture needling, any sensory nerve fiber, sensitized or not sensitized, will produce and send electrical signals to the spinal cord and the brain. Important acupoints, such as the 24 primary acupoints, provide stronger signals, and “sham” acupoints provide weaker signals.

NEUROANATOMY OF 24 PRIMARY HOMEOSTATIC ACUPOINTS

For 30 years Dr. H.C. Dung studied the pathophysiology of HAs in both clinical practice and laboratory research. He found that as many as 110 HAs may develop when homeostasis declines. Of these, 24 acupoints are the most important, as discussed previously.1

This discovery of HAs and their quantitative relation to homeostasis makes it possible to evaluate the pathophysiological condition (the self-healing potential) of a patient and predict the duration and prognosis of the acupuncture treatment (Chapter 6).

The 24 primary acupoints are named with their homeostatic sequence number, followed by the name of the related peripheral nerves or anatomic landmarks (see Figure 5-1). Consider, for example, the H1 deep radial acupoint. H1 means that this acupoint is the first of all the HAs to become tender on the body, and deep radial indicates that this acupoint is located on the deep radial nerve. Acupoint H19 infraorbital is located on the infraorbital foramen where the infraorbital nerve emerges and usually becomes tender after the H18 iliotibial point.

All the acupuncture needling methods described in the following section apply to prone or supine positions. The actual location of an acupoint varies in different patients. To achieve the best results, a practitioner should always palpate the body to locate the actual acupoints before needling them. The 24 primary homeostatic acupoints (see Figure 5-1) are described below according to body region.

Homeostatic Acupoints on the Head and Neck

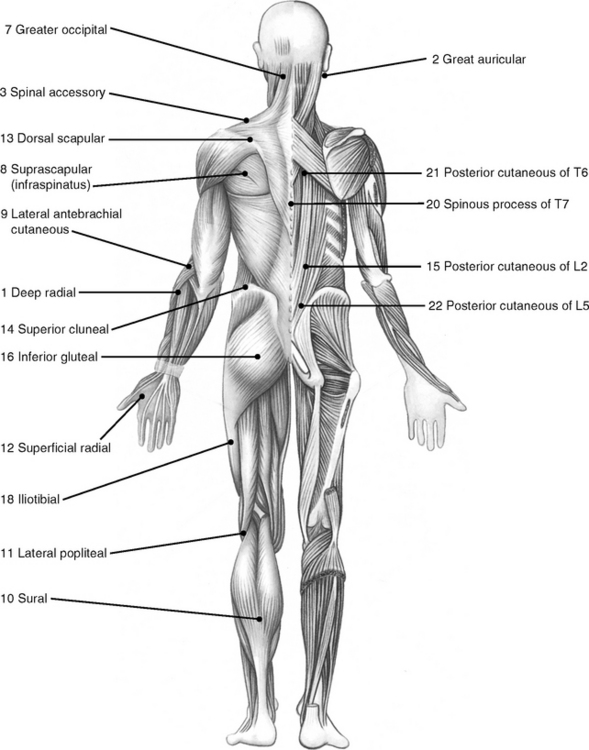

H19 Infraorbital

This acupoint is located exactly on the infraorbital foramen (Figure 5-2). The infraorbital nerve, a cutaneous nerve from the maxillary branch (V2) of the trigeminal nerve, passes the foramen and innervates the facial skin. To avoid hematoma use 38- or 36-gauge needles (diameter, 0.18 or 0.20 mm, respectively). The depth for needling ranges from 2 to 5 mm.

H23 Supraorbital

This acupoint is formed right on the supraorbital notch, which is the passage for the supraorbital nerve (see Figure 5-2). This cutaneous nerve from the ophthalmic branch (V1) of the trigeminal nerve extends to the top of the head. The method of needling this point is similar to the H19 infraorbital.

Clinical Notes

Because the supraorbital nerve is smaller than the infraorbital nerve, the H23 supraorbital becomes tender after the H19 infraorbital does (see Chapter 1). For example, the H19 infraorbital is always tender in a patient with a slight headache. If the headache lingers for some time, the H23 supraorbital becomes tender, too. If the headache continues to deteriorate, other points in the face, such as the mental nerve (V3), the zygomaticofacial nerve (V2), and the zygomaticotemporal nerve, also appear tender. More tender points indicate that the symptom is more chronic and more severe and requires more treatments.

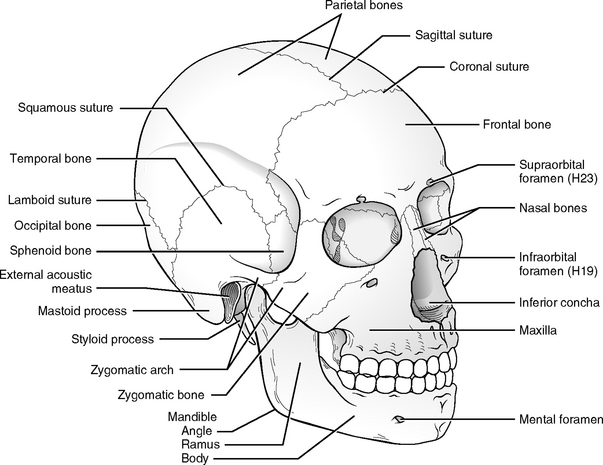

When treating patients with facial problems such as temporomandibular pain, chronic sinus pain, or facial paralysis, other points innervated by the facial nerve (VII) (Figure 5-3) should be carefully palpated and selectively needled according to the individual symptom.

H2 Greater Auricular

This acupoint is located just behind the earlobe and on the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (see Figure 5-3). The greater auricular nerve is one of the four branches from the cervical nerve plexus (CNP, C2-4). The anterior rami of C2 to C4 interconnect to form the cervical nerve plexus. The CNP lies deep below the internal jugular vein and the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Four cutaneous branches from the CNP emerge around the middle of the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

The greater auricular nerve curves over and ascends obliquely toward the earlobe and the angle of the mandible. This nerve bundle surfaces through the investing fascia just below the earlobe and divides into branches to supply the skin on the inferior part of the ear and the area extending from the mandible to the mastoid process. The three acupoints formed by the CNP are shown in Figure 5-3.

Clinical Notes

Several acupoints on the neck are formed by three other nerves derived from the CNP. These nerves are the (1) lesser occipital nerve, which forms an acupoint located on the insertions between the sternocleidomastoid and the trapezius muscles on the occipital bone; (2) the transverse cervical nerve, which curves around the middle of the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid and then passes transversely to the anterior border of the same muscle (several acupoints are formed over the anterior triangle of the neck); and (3) the supraclavicular nerve, which divides into medial, intermedial, and lateral branches. These nerves send small branches to the skin of the neck and then emerge from deep fascia just superior to the clavicle to supply the skin over the anterior aspect of the chest and shoulder. When needling tender acupoints in this area, a practitioner always should pay attention to the direction and depth of the needling so as not to puncture the lung. A safe needling method is suggested later in this chapter.

H7 Greater Occipital

This acupoint is located at the base of the occipital region, 2 or 3 cm from the midline (see Figure 5-1). This acupoint can be palpated easily because it is tender in more than 95% of patients. The dorsal rami of the C2 spinal nerve form the greater occipital nerve. This nerve emerges between the posterior arch of the atlas (C1) and the lamina of the axis (C2), below the small muscle obliquus capitis inferior. It then surfaces to supply the skin of the occipital region.

Clinical Notes

The H7 great occipital is frequently used because many symptoms can be traced to the problems of the neck. Neck-related problems are discussed in detail in Chapter 9. For effective treatment, we usually use needles of gauge 34 (diameter: 0.22 mm). The depth varies from 2 to 4 cm, depending on the thickness of the patient’s neck tissues.

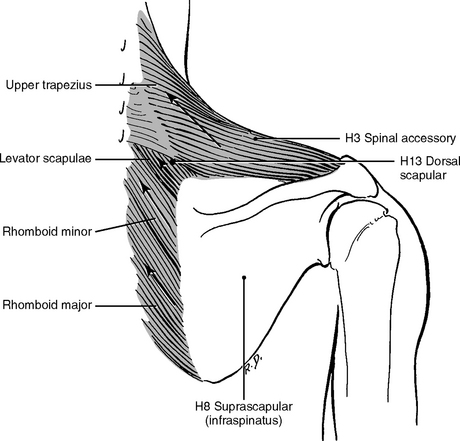

H3 Spinal Accessory

The spinal accessory nerve (XI) originates from both cranial roots (nucleus ambiguus in medulla) and spinal roots (C1 to C6), and it contains both afferent (sensory) and efferent (motor) fibers. The branch of the spinal accessory nerve enters the trapezius muscle at the point over the shoulder bridge in the middle of the front edge of the upper trapezius muscle (see Figure 5-1). This acupoint is a neuromuscular attachment point.

Clinical Notes

The H3 spinal accessory appears tender in more than 98% of the population. We use a needle no more than 2.5 cm long and insert the needle perpendicularly to the skin. Practitioners should be extremely careful when needling this point because the apex of the lung is just below this point. We suggest four needling methods in Chapter 9. A practitioner can choose the method he or she is most comfortable with or explore other safe methods. Another branch of the spinal accessory nerve also innervates the sternocleidomastoid muscle, but the acupoints formed in that muscle are less important.

Other Facial Acupoints

Two cranial nerves, the trigeminal nerve (V) and the facial nerve (VII; see Figure 5-3), are involved in the formation of facial acupoints. The trigeminal nerve contains both sensory (afferent) and motor (efferent) nerves and is responsible for general sensations in the skin of the face and front of the head as well as controlling the chewing muscles. The two types of facial muscles are the muscles of mastication (chewing) and the muscles of facial expression. Two important muscles of mastication, the temporalis and masseter muscles, are innervated by the motor nerves of the trigeminal nerve. The acupoints formed in those two muscles are essential in treating some headaches and facial symptoms such as temporomandibular joint syndrome (TMJ) and facial paralysis.

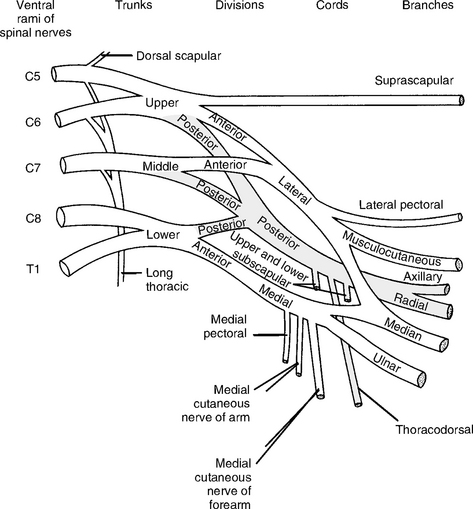

Homeostatic Acupoints on the Upper Extremity

The large nerve network of the brachial plexus supplies the upper extremities. The brachial plexus is formed by the union of the ventral rami of nerves C5 to C8 and most of the ventral ramus of T1 (Figure 5-4). To supply the upper extremities, these five rami interconnect to form three nerve trunks: upper (C5-6), middle (C7), and lower (C8 and T1). Each trunk splits into anterior and posterior divisions. All the posterior divisions unite to become the posterior cord, which has two major nerves, the axillary and radial nerves. The anterior divisions form the lateral cord and the medial cord. The lateral cord becomes the musculocutaneous nerve, and the medial cord the ulnar nerve. The union of fibers from both the lateral and the medial cords forms the median nerve. The small branches from the upper trunk and the three cords supply the shoulder (back and front); the five major terminal nerves are made up of the three cords innervating the free arm. Six primary homeostatic acupoints are located in the upper extremities: one on the chest, two on the shoulder, two on the forearm, and one on the hand. Here we discuss only the major nerves that give rise to the primary homeostatic acupoints.

Figure 5-4 Diagram of the brachial plexus. The small nerve to the subclavius, from the upper trunk, is omitted.

(Modified from Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders.)

H17 Lateral Pectoral

As one of the small terminal branches of the lateral cord, the lateral pectoral nerve (C5-7) pierces the clavipectoral fascia and enters the pectoralis major muscle at the spot about 4 to 5 cm inferior to the middle point of the clavicular bone (collarbone) (see Figure 5-1). A commonly used acupoint is formed at this neuromuscular attachment point.

Clinical Notes

The lateral pectoral nerve also sends a branch laterally to the medial pectoral nerve, which supplies the pectoralis minor muscle and forms an acupoint. The lateral pectoral nerve is so named because it arises from the lateral cord of the brachial plexus. Note that H17 lateral pectoral acupoint is located medially on the pectoralis major and the medial pectoral nerve is on the pectoralis minor lateral to the H17 lateral pectoral acupoint.

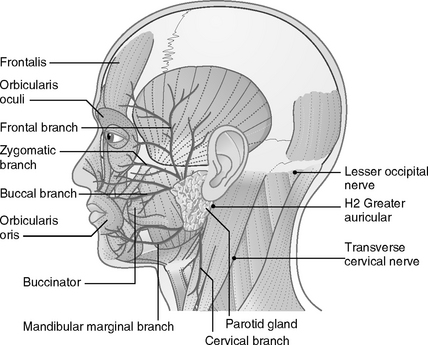

H9 Lateral Antebrachial Cutaneous

This acupoint is located at the lateral end of the skin crest at the elbow joint and is easy to detect when the forearm is flexed at a 90-degree angle (Figure 5-5). The musculocutaneous nerve (C5-7) from the lateral cord of the brachial plexus courses along the lateral side of the arm and pierces the deep fascia at the lateral edge of the cubital fossa to become the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve. An acupoint is formed at the location where the nerve pierces the deep fascia.

H1 Deep Radial

The H1 deep radial can be detected by palpation in more than 99% of the population (see Figure 5-5). The deep radial nerve (C5-8 and T1) is one of the terminal branches from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus (see Figure 5-4). This nerve provides the major nerve supply to the extensor muscles of the upper extremities: triceps, anconeus, brachioradialis, and all the extensor muscles of the forearm. It also supplies cutaneous sensation to the skin of the extensor region, including the hand.

The radial nerve leaves the axilla and runs posteriorly, inferiorly, and laterally between the long and medial heads of the triceps muscle. It enters the radial groove in the humerus. The radial nerve penetrates the lateral intermuscular septum of the arm and divides into two terminal branches: the deep and the superficial radial nerves. The first tender HA of our body is located at the branching spot, which is about 4 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle between the brachioradialis muscle and the extensor carpi radialis longus muscle. Here the deep radial nerve is accompanied by the radial artery and vein and their tributaries. As the deep radial nerve runs distally to the wrist from this point, it sequentially gives branches to nine muscles.

Clinical Notes

The H1 deep radial is the first acupoint to become tender in our body, and it can be used in every treatment to improve homeostasis; however, its clinical value rests more in diagnosis. Remember that the efficacy and prognosis of acupuncture therapy depend first on the self-healing capability of the body. As homeostasis declines, the self-healing potential drops, and more tender points gradually display along the deep radial nerve distally from the H1 deep radial. Thus the number of tender points appearing on the deep radial nerve provides quantitative information about the body’s homeostasis and self-healing potential. The diagnostic method is detailed in Chapter 6. The H1 deep radial acupoint can be needled all the way down to the bone below.

H13 Dorsal Scapular

The dorsal scapular nerve branches from the ventral ramus of C5 and descends from the cervical region down to the medial border of the scapula. It innervates three muscles: the levator scapulae, the rhomboid major, and the rhomboid minor. This nerve enters the levator scapulae muscle about 1 cm superior to the base of the spine of the scapula (Figure 5-6). The H13 dorsal scapular acupoint is formed at this neuromuscular attachment.

Clinical Notes

H8 Infraspinatus

This acupoint (Figures 5-1 and 5-6) is so named because it is located right on the infraspinatus muscle. The infraspinatus and the supraspinatus muscles are all innervated by the same nerve: the suprascapular nerve.

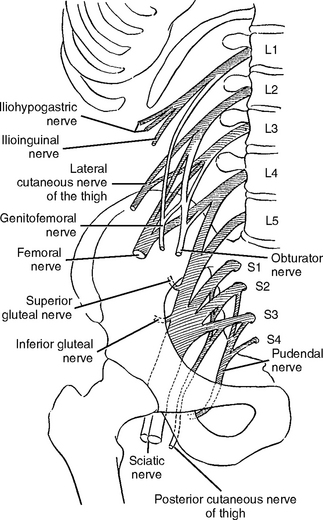

Homeostatic Acupoints on the Lower Extremities

The lower extremity, its bone, joints, muscles, and skin are innervated by nerves from both the lumbar nerve plexus (LNP) and the sacral nerve plexus (SNP). All the spinal nerves have dorsal and ventral rami. Only ventral rami of the lumbar and sacral spinal nerves are interconnected to form the LNP and SNP. Collectively we call them the lumbosacral plexus (LSP) (Figure 5-7). Just like the brachial plexus, the LSP divides to give off the anterior and the posterior divisions. The posterior divisions form the two major nerves: the femoral and the common fibular nerves. The anterior divisions form the two major nerves: the obturator and the tibial nerves. The tibial nerve gives two terminal branches: the medial plantar and the lateral plantar nerves. The common fibular and tibial nerves compose the sciatic nerve on the thigh region.

Figure 5-7 Diagram of the lumbosacral plexus.

(From Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders.)

H16 Inferior Gluteal

The H16 inferior gluteal is located in the center of the gluteal region (see Figure 5-1). The inferior gluteal nerve arises from the posterior divisions of the ventral rami of L5, S1, and S2. It leaves the pelvis through the inferior part of the greater sciatic foramen and inferior to the piriformis muscle, accompanied by the gluteal artery. This nerve enters the gluteus maximus muscle deeply from underneath.

H18 Iliotibial

This acupoint can be palpated on the lateral surface of the thigh, about halfway between the hip and the knee on the iliotibial tract (see Figure 5-1). Possibly the sciatic nerve sends cutaneous branches to innervate the iliotibial tract.

Clinical Notes

The H18 iliotibial is used in treating lower back and lower extremity problems. It should be noted that as the symptoms become worse or chronic, more tender points appear on the iliotibial tract. These secondary or tertiary points should be palpated and needled to achieve better and faster results. The needling depth can be all the way to the bone.

H11 Lateral/Medial Popliteal

These acupoints are located either on the lateral side of the tendon of the semitendinosus muscle (H11 medial popliteal) or on the medial side of the tendon of the biceps femoris (H11 lateral popliteal) (see Figure 5-1). The tenderness of these points can be palpable in most patients on the lateral side, the medial side, or on both sides.

H4 Saphenous

The H4 saphenous is easily palpable on the medial side of the knee below the medial condyle of the tibia (see Figure 5-1). This point is tender in almost every patient.

The H4 saphenous is formed at the site where the saphenous nerve emerges from the deep fascia. The saphenous nerve is a cutaneous branch of the femoral nerve that descends through the femoral triangle. This nerve accompanies the femoral artery and vein, and its branches supply the skin and fascia of the anterior and medial surface of the knee and leg as far as the medial malleolus.

H24 Common Fibular (Peroneal)

The H24 common fibular is located just anteroinferior to the head of the fibula (see Figure 5-1). The common fibular nerve is one of the two terminal branches of the sciatic nerve. The finger-width sciatic nerve, the largest nerve in the body, is formed by the ventral rami of L4 to S3. It leaves the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen and runs inferolaterally deep to the gluteus maximus. As it descends in the midline of the thigh, this nerve is overlapped posteriorly by the adjacent margins of the biceps femoris and semimembranosus muscles. In the lower third of the thigh, it divides into the tibial and the common fibular nerves.

H10 Sural

This acupoint is palpable around the middle of the posterior aspect of the leg, between the two heads of the gastrocnemius muscle (see Figure 5-1). As mentioned, the sciatic nerve contains two nerves, the common fibular and the tibial. These two nerves separate before they enter the popliteal fossa, where the common tibial nerve forms a branch termed the lateral sural nerve, and the tibial nerve forms the medial sural nerve. These two branches descend and unite between the two heads of the gastrocnemius muscle to form the sural nerve. The sural nerve pierces the deep fascia around the middle of the posterior leg where the acupoint is formed. The sural nerve is then joined by the fibular communicating branch of the common fibular nerve.

H6 Tibial

The H6 acupoint is palpable on the medial aspect of the leg, about 6 to 8 cm above the medial malleolus (see Figure 5-1). The tibial nerve is the larger terminal branch of the sciatic nerve (L4 to S3). The tibial nerve descends through the middle of the popliteal fossa, straight down the median plane of the calf, deep to the soleus muscle, and it supplies all the muscles in the posterior compartment of the leg. In addition, the tibial nerve gives off a cutaneous branch to form the sural nerve. The tibial nerve comes close to the medial skin about 6 to 8 cm above the medial malleolus, where the important H6 tibial acupoint is formed. From this point the tibial nerve courses down and passes deep to the flexor retinaculum between the medial malleolus and calcaneus. Here the tibial nerve divides into the medial and lateral plantar nerves and the calcaneal branches, which supply the skin of the sole and heel.

Homeostatic Acupoints on the Back

H20 Spinous Process of T7

This acupoint is located right on the spinous process of T7 (see Figure 5-1). The tenderness at this point is palpable in 80% of patients. The tissues of this acupoint are mainly innervated by small branches from the posterior primary ramus of the seventh thoracic spinal nerve.

H21 Posterior Cutaneous of T6

The H21 posterior cutaneous acupoint is located about 3 cm lateral from the spinous process of C6 (see Figure 5-1). It is tender in 80% of our patients. This acupoint is supplied by the cutaneous branch and the medial branch of the posterior primary ramus of the T6 spinal nerve. A 2.5-cm-long needle should be tilted toward the midline and inserted to a depth of about 2 cm.

H15 Posterior Cutaneous of L2

This acupoint is tender in about 90% of patients (see Figure 5-1). In most patients it lies on the lateral border of the lower back muscle (erector spinae), level with the narrowest part of the waist. In patients with much subcutaneous fat, a practitioner can palpate the lowest edges of the rib cage on both sides and draw an imaginary line between them. This point lies on the crossing point of this line and the lateral border of the erector spinae muscle. An experienced practitioner can easily locate the spinous process of L2 and find this acupoint quickly by palpating the erector spinae muscle in the lumbar region.

H22 Posterior Cutaneous of L5

To locate this point, it is better to locate the H15 posterior cutaneous of the L2 or spinous process of L2 first and then palpate down to locate the spinous processes of L4 and L5. This point is located about 3 cm from the spinous process of L5 (see Figure 5-1) on the bulge of the erector spinae muscle. In some people this point is closer to L4 and in others it is closer to L5. This point is innervated by the muscular branch of the posterior primary ramus of the spinal nerve of L5.

H14 Superior Cluneal

This point is located at the highest point of the iliac crest (see Figure 5-1). First the iliac crest should be palpated to locate this acupoint, which is tender in about 90% of patients. The lateral branches of the posterior primary rami of the first three lumbar nerves unite to form the superior cluneal nerves. The superior cluneal nerves take an oblique downward course to the buttock region and emerge from the deep fascia just superior to the iliac crest. These nerves supply the skin on the superior two thirds of the buttock.

SYMPTOMATIC (OR ASHI) ACUPOINTS AND THEIR SPINAL MECHANISMS

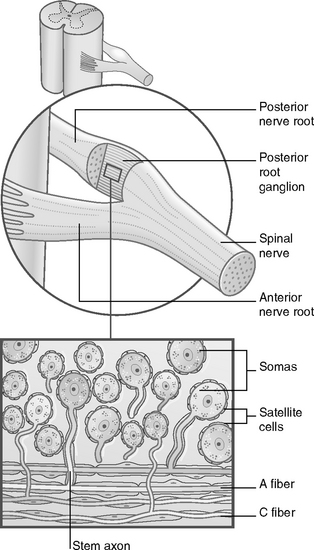

The body of a sensory neuron is housed in the dorsal (posterior) root ganglion (DRG), which is outside the spinal cord (Figure 5-8). This sensory neuron sends the nerve fiber peripherally to the skin or muscle and an axon centrally to the spinal cord gray matter. Pain is perceived by the brain if the peripheral nerve fibers are sensitized by pathological factors and send nociceptive signals to the brain.

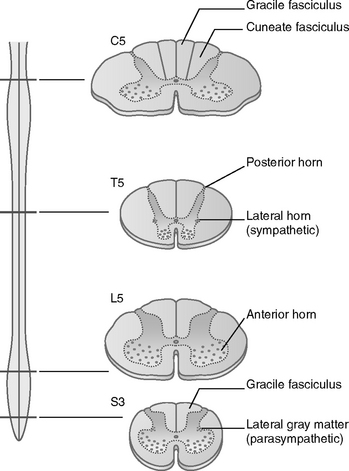

The spinal cord gray matter contains different neurons and is divided into three parts: the dorsal (posterior) horn, the lateral horn, and the ventral (anterior) horn (Figure 5-9). The neurons in the dorsal (posterior) horn form a synapse with the axons from the sensory neuron of the DRG.

The motor ventral horn controls muscle movement. It is important to keep in mind that the sensitized sensory fibers will, in their turn, sensitize the motor neurons, which will cause muscle shortening or stiffness of the muscles (see Chapter 3). The shortened muscles on the back can lead to blocked vertebral joints, resulting in stiffness of the neck and back, or they can create injuries to other shortened skeletal muscles and restrict the power of normal movement.

This spinal sensitization causes increased sympathetic activity, which affects the motor nerves and the postganglionic nerves. This process leads to vasoconstriction (constriction of the blood vessels) and muscle tension. Once this vicious circle is established, the local nerve fibers become more sensitive and influence more nerve fibers and other soft tissues and finally result in the local tissues reacting abnormally to mechanical, thermal, and chemical stimuli (see Chapter 3).

This pathologic phenomenon is named hyperalgesia (painful sensation) or hyperesthesia (sensation of discomfort). Local tender points are created by the acute onset of diseases/injuries or chronic diseases.

Treatment Protocol

Healthy people may have only a few tender homeostatic acupoints with minimal sensitivity, and the neurons in their spinal cord may be barely sensitized. If acute symptoms develop, the number and sensitivity of the local tender acupoints will increase. At this acute stage, the peripheral nerve fibers of the acupoints become sensitized but the neurons in the corresponding segment of the spinal cord are still not sensitized. For such patients a few acupuncture sessions will desensitize the peripheral nerve fibers and the symptoms will be permanently cured.

Thus, to treat chronic symptoms, we needle both SAs and HAs. The needling will activate the spinal segmental (SAs) and supraspinal (HAs) mechanisms (see Figure 3-2, p. 33). In other words, to treat chronic pain, we need to desensitize both peripheral nerves and the spinal cord. This is why chronic pain requires more acupuncture treatments than acute pain.

Now it is clear why acupuncture sometimes produces “miracles” in reasonably healthy persons experiencing acute pain: a few needles and two to four sessions can cure the problems permanently. More treatment sessions will be required to reduce symptoms in chronic pain patients, and the symptoms are likely to recur after some time. For a few patients with severely impaired homeostasis, acupuncture therapy provides little or no relief no matter how many treatments are offered. The difference between these three groups of patients (strong, average, and weak responders to acupuncture) is that the neurons responsible for pain perception in their spinal cords and brains have different pathologic sensitivities.

The following are some examples of SA formation. The respiratory symptoms from allergy, lung infection, or asthma will make acupoints tender on the front of the chest and the upper back. These points are often innervated by the cutaneous and muscular nerves from anterior and posterior rami of the spinal nerves of T1 to T8 (see Figure 5-13). An acute or chronic gastritis gives tender points just below the front rib cage on the rectus abdominis muscle and on the back along T5 to T11. If an athlete sprains an ankle, tender or even painful points appear around the injured ankle area, which is innervated by the fibular and tibial nerves derived from L3 to S3. Tennis elbow and carpal tunnel syndrome are related to the brachial plexus from C5 to T1. All these points are caused by either exogenous injuries or endogenous diseases, and they are locally restricted. If, however, the treatment of the pathologic condition is delayed, that is, if the SAs persist for some time, more tender points may develop far from the original symptomatic points. For example, some acute lower back pain produces tender points only on the lower back area or the gluteal region. If not properly treated, new tender points may appear on the thighs or legs and acute lower back pain will become chronic lower back pain, which will require more treatments to alleviate and may be subject to a relapse.

More clinical techniques and procedures are detailed in Chapter 6.

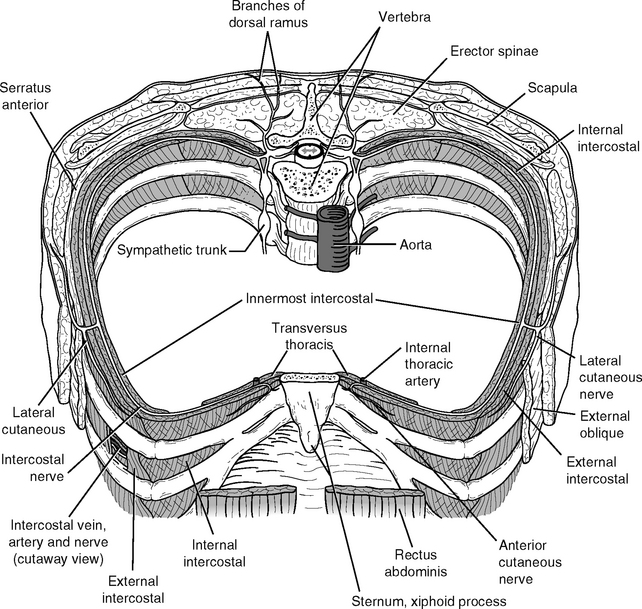

NEUROANATOMY OF THE PARAVERTEBRAL POINTS

Every spinal nerve divides into two primary rami: posterior (dorsal) and anterior (ventral) (Figure 5-10). The anterior primary ramus gives two branches: the lateral cutaneous and the anterior cutaneous nerves. Each cutaneous nerve separates into two end branches to supply side and anterior parts of the same dermatome.

The posterior primary ramus also separates into two end branches: lateral and medial. In the thoracic region, the lateral branches are muscular and the medial branches are cutaneous. Each end branch may form an acupoint when it penetrates the fascia to supply the skin. Thus a spinal nerve may form six tender acupoints in its dermatome at the locations where each of the branches penetrates the fascia. From the cervical region to the sacral region of the spine, there are 33 pairs of spinal nerves.

All facial acupoints are formed on the cranial nerves, and all body acupoints are associated with the spinal nerves. Once the spinal nerve leaves the intervertebral foramen, it divides into two major branches: the anterior primary ramus and the posterior primary ramus (see Figure 5-10).

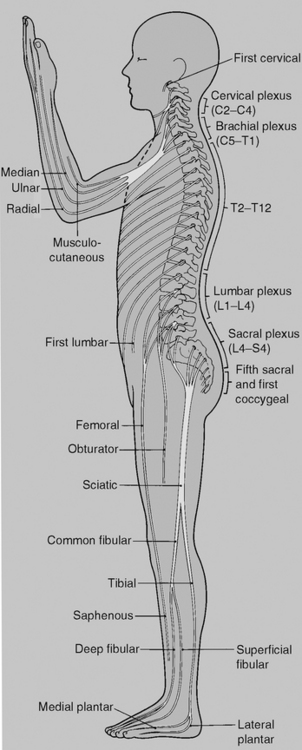

Most symptomatic and homeostatic acupoints are formed on the terminal branches of the anterior primary rami. A posterior primary ramus goes to the back and divides into two terminal branches: the medial branch and the lateral branch. In the thoracic region, the medial branch supplies the skin and the lateral branch supplies the muscles. The posterior primary ramus also sends small branches to innervate the vertebral joints. In general, there is a total of 33 posterior primary rami from the neck to the sacral region: 8 from cervical vertebrae (C1-8), 12 from thoracic vertebrae (T1-12), five from lumbar vertebrae (L1-5), 4 from sacral vertebrae (S1-4), and four (or three in some cases) from the coccygeal bones (Figure 5-11). The coccygeal spinal nerves are very small and are needled only in treating pain in the coccygeal regions.

Figure 5-11 Diagram of the distribution of the anterior rami of the spinal nerve. The posterior rami are short and innervate the muscles and skin of the back (not shown on this diagram but can be seen in Figure 5-10).

(Modified from Gosling J, et al: Human anatomy: color atlas and text, ed 4, Edinburgh, 2002, Mosby.)

PRINCIPLES OF USING SPINAL SEGMENTATION IN ACUPUNCTURE THERAPY

How to Select Paravertebral Acupoints

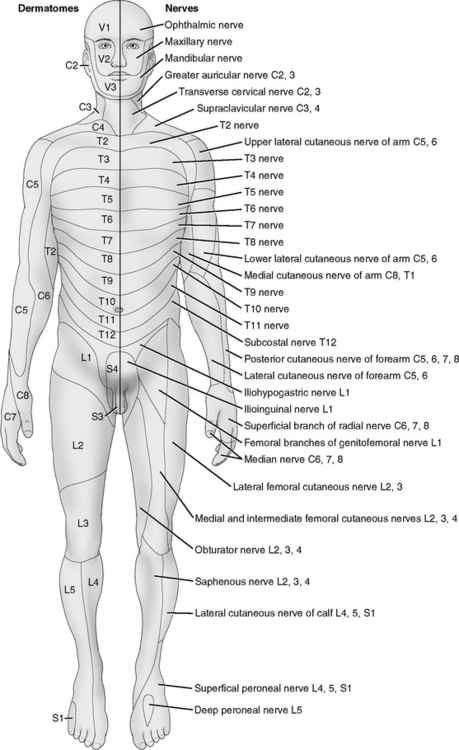

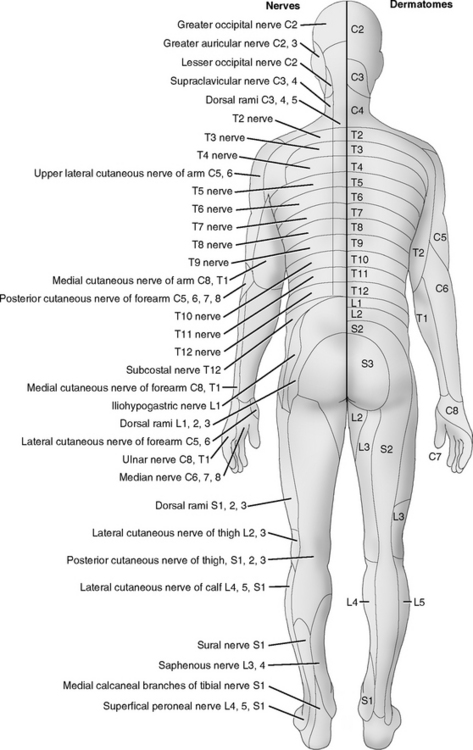

PAs are selected to match the corresponding SAs according to spinal segmentation. For symptoms of the upper extremity, needle PAs from C4 to T1. For lower-extremity disorders, use PAs along L2 to S3. PAs along T1 to T7 are used for problems of upper back and chest and PAs from T8 to L1 for problems of the abdominal region (Figures 5-11 to 5-13).

Segmental Innervation of the Skin: Dermatomes

In the trunk the cutaneous segmentation is in the form of dermatomes, which are arranged in regular bands from T2 to L1 (Figure 5-12). A few body marks can help with remembering the dermatomes: T2 is at the sternal angle, T10 at the level of the umbilicus, and L1 in the region of the groin. As mentioned, there is considerable overlap between neighboring dermatomes of the trunk. Thus, for clinical simplicity and efficacy, it is important to treat both affected dermatomes and their neighboring dermatomes. For example, if postherpetic neuralgia is associated with T5 and T6, the PAs of dermatome from T4 to T7 should be needled together.

Segmental Innervation of the Musculature: Myotomes

For clinical practicality and efficacy, acupuncture practitioners do not need to remember which single muscle is supplied by which single segmental nerve, but we do need to know what portion of the segments are related to the particular muscles. For example, elbow flexors are innervated by C5 and C6, extensors by C7 and C8. When we treat any elbow pain or even any upper-extremity problems, we simply needle PAs from C4 to T1. Table 5-1 is designed for this purpose. Readers may consult textbooks of neuroanatomy to study myotomes in more detail.

| Musculature of the Body Region | Segments of the Spinal Cord |

|---|---|

| Upper extremity (including shoulder) | C4-T1 |

| Lower extremity (including hip) | T12-S3 |

| Trunk | |

| Diaphragm | C1-5 |

| Other trunk and abdominal muscles | Regular segmental pattern from C5-S2 |

Segmental Innervation of the Skeletal System: Sclerotomes

Some patients seek acupuncture therapy for pain on the bones that may involve the inflammation of the periosteum. One common example is the pain on the shin bone (tibia). Knowledge of the segmental supply by the spinal nerves (sclerotomes) helps to select the proper PAs. Readers will find that the principle of using sclerotomes is actually very similar to that of myotomes (Table 5-2).

| Bones of the Body Region | Segments of the Spinal Cord |

|---|---|

| Cervical vertebrae | C1-8 |

| Upper extremity (including shoulder) | C4-T1 |

| Lower extremity (including hip) | T12-S3 |

| Trunk | |

| Costae | Regular pattern from T1-12 |

| Thoracic and lumbar vertebrae | Regular segmental pattern from T1-5 |

Segmental Innervation of the Internal Organs: Viscerotome

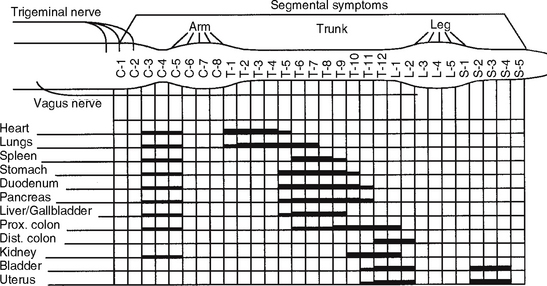

Some patients complain that their pain is related to internal organs such as stomach, kidneys, or gallbladder. Whereas the visceral pain can be relieved by acupuncture, these patients should be referred to internists. However, knowledge of segmental innervation of internal organs helps to select correct PAs to relieve pain or muscle spasm of the internal organs (Figure 5-13).

Figure 5-13 shows that most important internal organs are innervated by both cervical and thoracic nerves (including kidneys). Thus it is important to needle the cervical PAs when treating disorders of these organs.