Section 5 Chronic complications

Ocular complications

Clinically significant ocular complications associated with diabetes include:

• transient visual disturbances secondary to osmotic changes (or briefer episodes secondary to hypoglycaemia)

• retinopathy – the predominant cause of blindness in type 1 diabetes

• cataracts – develop earlier in diabetic patients

Diabetic retinopathy

Pre-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Pre-proliferative diabetic retinopathy is characterized by:

• vascular changes consisting of venous changes in the form of ‘beading’, ‘looping’ and ‘sausage-like’ segmentation. The arterioles may also be narrowed and even obliterated, resembling a branch retinal artery occlusion.

• cotton-wool spots, caused by capillary occlusion in the retinal nerve fibre layer. Interruption of axoplasmic flow caused by the ischaemia, and subsequent build-up of transported material within the nerve axons, is responsible for the white appearance of these lesions.

• dark blot haemorrhages, which represent haemorrhagic retinal infarcts.

• intraretinal microvascular anomalies (IRMAs), representing either dilated pre-existing vessels or early intraretinal new vessels. They are found within an area of capillary non-perfusion.

Classification of diabetic retinopathy

Conventionally involvement of retina in patients with diabetes has been classified as background, pre-proliferative retinopathy and proliferative retinopathy. Macula may be involved (maculopathy) with any of the above forms of retinopathy (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 Grading system used for screening for diabetic retinopathy (UK National Guidelines)

| RETINOPATHY (R) |

|

The presence of at least one of any of the following features anywhere: • Four or more blot haemorrhages in one hemi-field only (inferior and superior hemi-fields delineated by a line passing through the centre of the fovea and optic disc) Any of the following features: Any of the following features: |

IRMA, intraretinal microvascular anomaly.

Another commonly used grading system is the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) system (Table 5.2).

Table 5.2 The Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) system

| Grade | Features |

|---|---|

| NPDR | |

| None | Normal retina |

| Early | Microaneurysms only |

| Mild | Microaneurysms plus: |

| Moderate | Mild; NPDR plus: |

| Severe | Moderate NPDR plus 4/2/1 rule: |

| Very severe | Any two or more of the ‘severe categories’ |

| PDR | |

| PDR without HRC | NVE or NVD < ½DD |

| PDR with HRC | NVE or NVD > ½DD plus preretinal and/or vitreous haemorrhages |

DD, disc diameter; HRC, high-risk changes; IRMA, intraretinal microvascular anomaly; NPDR, non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy; NVD, new vessels on the disc; NVE, new vessels elsewhere in the retina; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Screening

Grading and quality assurance

Automated grading can operate as the initial screener to exclude a majority of images with ‘no retinopathy’ before manual grading. The specificity of automated grading is lower than for manual grading, for equivalent sensitivity. Automated grading may be used for distinguishing no retinopathy from any retinopathy in a screening programme providing validated software is used. It has a similar sensitivity for detecting referable retinopathy, but may be less sensitive at detecting diabetic maculopathy (Table 5.3).

General principles of management of diabetic retinopathy

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Neovascularization is the hallmark of PDR. New vessels are commonly seen along the retinal arcades, but can occur at the optic disc or elsewhere in the retina. As a general rule, the retina distal to the neovascularization should be considered as ischaemic, and it has been estimated that more than one-quarter of the retina has to be non-perfused before neovascularization occurs. Ischaemia upregulates the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) that stimulates neovascularization. New vessels start as endothelial proliferations, and pass through the internal limiting membrane to lie in the potential plane between the retina and the posterior vitreous face. PDR can result in visual deterioration from ischaemia, haemorrhage and tractional retinal detachment involving the macula (Table 5.4).

Table 5.4 Guidelines for referral for specialist assessment of diabetic retinopathy

| Clinical problem | Urgency (within) |

|---|---|

| Sudden loss of vision | 1 day |

| Evidence of retinal detachment | 1 day |

| New vessel formation (on the disc or elsewhere) | 1 week |

| Vitreous or pre-retinal haemorrhage | 1 week |

| Rubeosis iridis | 1 week |

| Hard exudates within 1DD of the fovea or clinically significant macular oedema | 4 weeks |

| Unexplained drop in visual acuity | 4 weeks |

| Unexplained retinal findings | 4 weeks |

| Severe or very severe non-proliferative retinopathy is present | 4 weeks |

Diabetic maculopathy

Diabetic maculopathy can present in the following patterns:

• Focal – focal leakage, characterized usually by the presence of a cluster of microaneurysms surrounded by retinal thickening and a complete or incomplete ring of hard exudates

• Diffuse – diffuse retinal thickening and exudation from capillaries often involving the fovea. Cystoid changes suggest chronicity of the condition

• Ischaemic – diagnosed ideally by fluorescein angiography, representing an enlarged or irregular foveal avascular zone. Clinically it may lack features; however, the hallmarks are reduced visual acuity, deep blot haemorrhages and IRMAs.

Vitrectomy

• Patients with type 1 diabetes and persistent vitreous haemorrhage should be referred for early vitrectomy.

• Vitrectomy should be performed in patients with tractional retinal detachment threatening the macula and should be considered in patients with severe fibrovascular proliferation.

• Patients with type 2 diabetes and vitreous haemorrhage that is too severe to allow photocoagulation should be referred for consideration of a vitrectomy.

Cataract extractions in patients with diabetes

Cataract

Diabetic neuropathy

Age

Diabetic neuropathy can manifest with a wide variety of sensory, motor and autonomic symptoms:

• Sensory symptoms may be negative or positive, diffuse or focal.

• Motor problems may include distal, proximal, or more focal weakness.

• The autonomic nervous system is composed of nerves serving the heart, skin, eyes, gastrointestinal system and genitourinary system. Autonomic neuropathy can affect any of these organ systems.

Classification of neuropathy

Symmetrical polyneuropathies

Symmetrical polyneuropathies involve multiple nerves diffusely and symmetrically:

• Distal symmetrical polyneuropathy:

• Diabetic autonomic neuropathy:

• Diabetic neuropathic cachexia:

Asymmetrical neuropathies

• Diabetic thoracic radiculoneuropathy:

• Diabetic radiculoplexus neuropathy:

Treatment

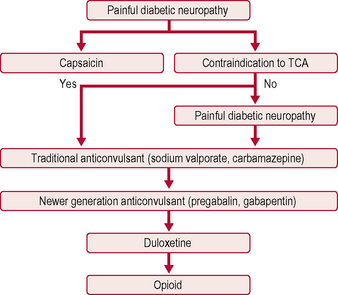

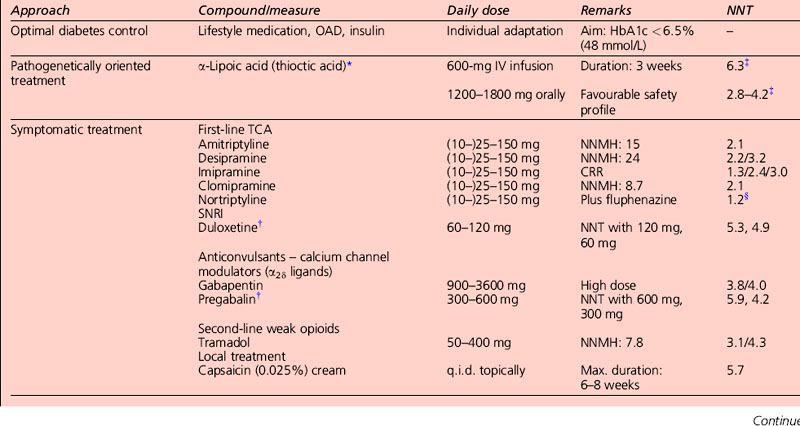

The only two drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for diabetic peripheral neuropathy are the antidepressant duloxetine and the anticonvulsant pregabalin (Fig. 5.1). Before trying a systemic medication, people with localized diabetic periperal neuropathy occasionally get relief from their symptoms with lidocaine patches.

Antiepileptic drugs

AEDs, especially gabapentin and the related pregabalin, have emerged as first-line treatment for painful neuropathy. Gabapentin compares favourably with amitriptyline in terms of efficacy, and is clearly safer. Its main side-effect is sedation, which does not diminish over time and may in fact worsen. It needs to be taken three times a day, and sometimes causes weight gain, which can worsen glycaemic control. Carbamazepine is effective but is associated with side-effects at higher doses. Topiramate has not been studied in diabetic neuropathy, but has the beneficial side-effect of causing mild anorexia and weight loss, and is anecdotally beneficial (Table 5.5).

Other treatments

Acupuncture may be of some benefit.

Sativex, a cannabis-based medication, has not been found to be effective for diabetic neuropathy.

Diabetic autonomic neuropathy

Diabetic foot disease

Motor neuropathy with the associated small muscle wasting can lead to clawing of toes and subluxation of the small joints that in turn cause pressure ulcers. Peripheral vascular disease in the form of macrovascular or microvascular disease is a component cause of one-third of foot ulcers, and is an important risk factor for recurrent ulcers. Patients with significant autonomic neuropathy may have bounding foot pulses yet severe microvascular disease in the distal limb (Table 5.6).

| Autonomic neuropathy | Motor neuropathy |

|---|---|

| Abnormal response to temperature | Intrinsic muscle weakness |

| Disorders of sweating | Claw toes |

| Brittle, dry skin | Retracted toes |

| Atrophy of fatty fibro-padding | Pes cavus |

| Oedema – arteriovenous shunting | Corn/callous |

• Nature of the colonizing flora: certain Gram-positive cocci such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes secrete a number of toxins and adhesion factors that allow them to colonize, invade and damage the tissues. Other β-haemolytic streptococci, such as those belonging to Lancefield group C, F and G, can also cause pyogenic infections. On the other hand, coagulase-negative staphylococci are often harmless commensals. Gram-negative organisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Proteus spp can lead to active infection and impair wound healing.

• Extent of tissue colonization: microbes that commonly lead to superficial colonization can nonetheless cause infections at deeper sites. Thus, coagulase-negative staphylococci that commonly colonize skin and its appendages can cause serious bone and joint infections provided they get an entry into these deeper areas of the body.

• Host defence mechanisms: if host defense mechanisms are compromised, a relatively non-virulent organism can occasionally cause quite severe infection.

Evaluation/screening of patients of the diabetic foot

The nature of the local pathology (both wound and the associated limb), assessment of the severity of infection, and presence of systemic illness each affect the ultimate outcome in an individual case. Earlier classification systems such as the Wagner dysvascular foot classification included all infections within a single category. More recently, the consensus classification developed by the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (Table 5.7) uses grades of severity as a tool in classifying the foot infections. Successful management of diabetic foot infections involves recognition that infection is by no means one entity. Rather, this patient-centred approach lays great emphasis on making distinctions based on response to infection, and not infection itself. For example, systemic illness categorizes patients in grade 4 severity although the local wound may be only moderately inflamed. This classification also removes ambiguity with regards to terms such as ‘complicated’ wound.

Table 5.7 Clinical classification of diabetic foot infection

| Clinical manifestation | Infection severity | PEDIS grade* |

|---|---|---|

| Wound lacking purulence or any manifestation of inflammation | Uninfected | 1 |

| Two or more manifestations of inflammation, but cellulitis or erythema extends ≤ 2 cm around the ulcer with infection limited to the skin or superficial subcutaneous tissues. No other local complications and no systemic illness | Mild | 2 |

| Infection as above in a patient who is systemically well and metabolically stable but with one or more of the following: cellulitis extending > 2 cm, lymphangitic streaking, spread beneath the superficial fascia, deep tissue abscess, gangrene, and involvement of muscle, tendons joint or bone | Moderate | 3 |

| Infection in a patient with systemic toxicity and metabolic instability (e.g. fever, chills, tachycardia, hypotension, confusion, vomiting, leukocytosis, acidosis, severe hyperglycaemia, azotaemia) | Severe | 4 |

* PEDIS is an acronym for perfusion, extent, depth, infection, sensation.

Preventive management

Patient education

• buying well-fitting new shoes with low heels (no more than 1¼ inches)

• where possible the uppers should be made of natural materials (e.g. leather)

• trying on both shoes before purchase

• checking their shoes for sharp objects and for wear and tear, buying a well-fitting shoe, boot or trainer with laces or a strap fastening.

Management of active foot disease

Diabetic nephropathy

Definitions

With the advent of reporting of estimated GFR (eGFR), increasing numbers of people are being identified with a sustained low GFR. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the absence of proteinuria would not previously be classified as having diabetic kidney disease (Table 5.8).

| Stage | Description | GFR (ml per min per 1.73 m2) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kidney damage* with normal or raised GFR | ≥ 90 |

| 2 | Kidney damage* with mild decrease in GFR | 60–89 |

| 3A | Moderately lowered GFR | 45–59 |

| 3B | 30–44 | |

| 4 | Severely lowered GFR | 15–29 |

| 5 | Kidney failure (endstage renal disease) | < 15 |

If proteinuria (24-h urine > 1 g per day or urine protein/creatinine ratio (PCR) > 100 mg/mmol) is present, the suffix P may be added. Patients on dialysis are classified as stage 5D. The suffix T indicates patients with a functioning renal transplant (can be stages 1–5).

GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

* Kidney damage defined as abnormalities on pathologic, urine, blood, or imaging tests.

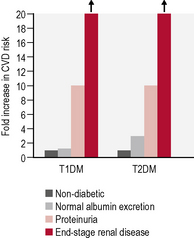

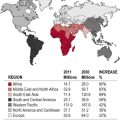

Prevalence and progression of kidney disease in diabetes

The number of patients with diabetes requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT) is increasing.

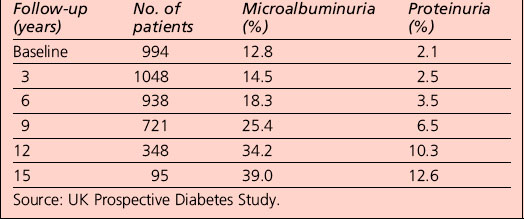

Microalbuminuria and proteinuria

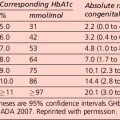

In people with type 1 diabetes, the cumulative incidence of microalbuminuria at 30 years’ disease duration is approximately 40%. For microalbuminuric patients, the relative risk of developing proteinuria is 9.3 compared with that in normoalbuminuric patients. Some 25% of individuals who were in the conventional arm of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) had proteinuria, raised serum creatinine levels (> 177 μmol/L) and/or were on RRT after 30 years of diabetes. Data from type 2 patients is available from the UKPDS and is presented in Table 5.9.

Management of diabetic nephropathy

Management of established diabetic kidney disease

Diabetic cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular risk factors

Pharmacological therapy

Antihypertensive therapy

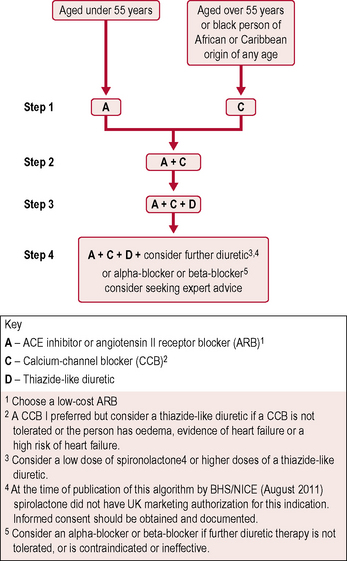

The British Hypertension Society A/CD algorithm (Fig. 5.3) has been accepted as the best method of defining combination drug therapy. It specifies the use of ACE inhibitors (or ARBs if intolerant), calcium channel blockers and thiazide-type diuretics.

Patients with diabetes requiring antihypertensive treatment should be commenced on:

Acute coronary syndromes

Primary coronary angioplasty

Patients with ST elevation acute coronary syndrome should be treated immediately with primary PCI.

Management of patients with diabetes and stable angina

Acute stroke

Patients should be given information to help them recognize the following risk factors:

Treatment of acute stroke

Secondary treatment

• Patients with diabetes and new or established CVD should be offered treatment similar to the secondary prevention of coronary artery disease.

• Patients should be encouraged to take advantage of all cardiac rehabilitation programmes offered.

• The Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events (CAPRIE) study showed that the combination of clopidogrel with aspirin was superior to aspirin alone.

• Aggressive lipid lowering with LDL targets < 100 mg/dL (4 mmol/L) and preferably < 70 mg/dL (2 mmol/L) have been advocated.

• Patients with carotid artery disease benefit from carotid end-arterectomy or stenting if the degree of stenosis is > 70%.

• Patients with diabetes with atrial fibrillation should be anticoagulated.

Dermatological features of diabetes mellitus

• Type A – genetic defects in the insulin receptor or postreceptor mechanisms

• Type B – acquired insulin resistance, due to autoantibodies directed against the insulin receptor.

Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disease

Fibroproliferative disorders of soft tissue

Skeletal disease in diabetes

Infection and diabetes

Predisposing factors

• Physical factors. Severe invasive infections may develop because of particular predisposing factors that arise from the diabetic state. For example, chronic complications such as foot ulcers provide a portal of entry of microorganisms to soft tissues and bone. Polymicrobial infections are usual in this situation. Autonomic neuropathy (see p. 187) predisposes to urinary stasis and ascending infections. Pyelonephritis is occasionally complicated by necrosis and sloughing of renal papillae demonstrable on retrograde pyelography. Necrotizing otitis externa may be encountered, particularly in elderly diabetic patients.

• Metabolic factors. The ability of neutrophil leukocytes to migrate, ingest and kill organisms may be compromised by hyperglycaemia; overactivity of the polyol pathway is implicated. Through stimulation of counter-regulatory hormone secretion and cytokine release (tumour necrosis factor-α and interleukins induce insulin resistance), infections may lead to a deterioration in metabolic control; infections are the commonest identifiable precipitating cause of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) (see p. 143).

Attainment of good metabolic control is therefore important in the management of infections in diabetic patients; this may necessitate temporary insulin therapy in diet- or tablet-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. The association between the rare and serious complication of invasive infection with the saprophytic Mucor species (rhinocerebral mucormycosis) with DKA (see p. 143) is noteworthy; this condition is encountered in some other states associated with severe metabolic acidosis.

Viral infections

As discussed in Section 1, some viruses (rubella, mumps, Coxsackie B4) have been implicated in the aetiology of type 1 diabetes. Intrauterine rubella infection leads to autoimmune type 1 diabetes in 20–40% of children. Recent concerns that immunization against common childhood infections might lead to an increased risk of type 1 diabetes have not been substantiated.