CHAPTER 5 Child, Adolescent, and Adult Development

MAJOR THEORIES OF DEVELOPMENT

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939)

Freud’s developmental theory is closely tied to his drive theory, which is best described in his 1905 work, Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality.1 In these essays, Freud outlined his theory of childhood sexuality and portrayed child development as a process that unfolds across discreet, universal, stages. He posited that infants are born as polymorphously perverse, meaning that the child has the capacity to experience libidinal pleasure from various areas of the body. Freud’s stages of development were based on the area of the body (oral, anal, or phallic) that is the focus of the child’s libidinal drive during that phase (Table 5-1). According to Freud, healthy adult function requires successful resolution of the core tasks of each developmental stage. Failure to resolve the tasks of a particular stage leads to a specific pattern of neurosis in adult life.

| Sigmund Freud: Psychosexual Phases | Erik Erickson: Psychosocial Stages | Jean Piaget: Stages of Cognitive Development |

|---|---|---|

| Oral (birth-18 mo) | Trust vs. Mistrust (birth-1 yr) | Sensorimotor (birth-2 yr) |

| Anal (18 mo-3 yr) | Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt (1-3 yr) | Preoperational (2-7 yr) |

| Phallic (3-5 yr) | Initiative vs. Guilt (3-6 yr) | |

| Latency (5-12 yr) | Industry vs. Inferiority (6-12 yr) | Concrete operations (7-12 yr) |

| Genital (12-18 yr) | Identity vs. Role Confusion (12-20 yr) | Formal operations (11 yr-adulthood) |

Around 18 months of age, the oral phase gives way to the anal phase. During this phase, the focus of the child’s libidinal energy shifts to his or her increasing control of bowel function through voluntary control of the anal sphincter. Failure to successfully negotiate the tasks of the anal phase can lead to the anal-retentive character type; affected individuals are overly meticulous, miserly, stubborn, and passive-aggressive, or the anal-expulsive character type, described as reckless and messy.

Around 3 years of age, the child enters into the phallic phase of development, during which the child becomes aware of the genitals and they become the child’s focus of pleasure.2 The phallic phase, which was described more fully in Freud’s later work, has been subjected to greater controversy (and revision by psychoanalytic theorists) than the other phases. Freud believed that the penis was the focus of interest by children of both genders during this phase. Boys in the phallic phase demonstrate exhibitionism and masturbatory behavior, whereas girls at this phase recognize that they do not have a phallus and are subject to penis envy.

Late in the phallic phase, Freud believed that the child developed primarily unconscious feelings of love and desire for the parent of the opposite sex, with fantasies of having sole possession of this parent and aggressive fantasies toward the same-sex parent. These feelings are referred to as the Oedipal complex after the figure of Oedipus in Greek mythology, who unknowingly killed his father and married his mother. In boys, Freud posited that guilt about Oedipal fantasies gives rise to castration anxiety, which refers to the fear that the father will retaliate against the child’s hostile impulses by cutting off his penis. The Oedipal complex is resolved when the child manages these conflicting fears and desires through identification with the same-sex parent. As part of this process, the child may seek out same-sex peers. Successful negotiation of the Oedipal complex provides the foundation for secure sexual identity later in life.3

At the end of the phallic phase, around 5 to 6 years of age, Freud believed that the child’s libidinal drives entered a period of relative inactivity that continues until the onset of puberty. This period is referred to as latency. This period of calm between powerful drives allows the child to further develop a sense of mastery and ego-strength, while integrating the sex-role defined in the Oedipal period into this growing sense of self.1

With the onset of puberty, around 11 to 13 years of age, the child enters the final developmental stage in Freud’s model, called the genital phase, which continues into young adulthood.3 During this phase, powerful libidinal drives resurface, causing a reemergence and reworking of the conflicts experienced in earlier phases. Through this process, the adolescent develops a coherent sense of identity and is able to separate from the parents.

Erik Erikson

Erik H. Erikson (1902-1994) modified the ideas of Freud and formulated his own psychoanalytic theory based on phases of development.4 Erikson came to the United States just before World War II; as the first child analyst in Boston. He studied children at play, as well as Harvard students, and he studied a Native American tribe in the American West. Like Freud, he presented his theory in stages; and like Freud, he believed that problems present in adults are largely the result of unresolved conflicts of childhood. However, Erikson’s stages emphasize not the person’s relationship to his or her own sexual urges and instinctual drives, but rather, the relationship between a person’s maturing ego and both the family and the larger social culture in which he or she lives.

Erikson proposed eight developmental stages that cover an individual’s entire life.4 Each stage is characterized by a particular challenge, or what he called a “psychosocial crisis.” The resolution of the particular crisis depends on the interaction between an individual’s characteristics and the surrounding environment. When the developmental task at each stage has been completed, the result is a specific ego quality that a person will carry throughout the other stages. (For example, when a baby has managed the initial stage of Trust vs. Mistrust, the resultant ego virtue is Hope.)

It should be noted that Erikson did not believe that a person could be “stuck” at any one stage; in his theory, if we live long enough we must pass through all of the stages. The forces that push a person from stage to stage are biological maturation and social expectations. Erikson believed that success at earlier stages affected the chances of success at later ones. For example, the child who develops a firm sense of trust in his or her caretakers is able to leave them and to explore the environment, in contrast to the child who lacks trust and who is less able to develop a sense of autonomy. But, whatever the outcome of the previous stage, a person will be faced with the tasks of the subsequent stage.

Jean Piaget

Like Erikson, Jean Piaget (1896–1980) was another developmental stage theorist. Piaget was the major architect of cognitive theory, and his ideas provided a comprehensive framework for an understanding of cognitive development. Piaget first began to study how children think while he was working for a laboratory, designing intelligence testing for children. He became interested not in a child answering a question correctly, but rather, when the child’s answer was wrong, why it was wrong.5 He concluded that younger children think differently than do older children. Through clinical interviews with children, watching children’s spontaneous activity, and close observations of his own children, he developed a theory that described specific periods of cognitive development.

Piaget maintained that there are four major stages: the sensorimotor intelligence period, the preoperational thought period, the concrete operations period, and the formal operations period (see Table 5-1).6 Each period has specific features that enable a child to comprehend certain kinds of knowledge and understanding. Piaget believed that children pass through these stages at different rates, but maintained that they do so in sequence, and in the same order.

These “mental actions” enable children to think systematically and with logic; however, their use of logic is limited to mostly that which is tangible.6 The final stage of Piaget’s cognitive theory is formal operations, which occurs around age 11 and continues into adulthood. In this stage, the early adolescent and then the adult is able to consider hypothetical and abstract thought, can consider several possibilities or outcomes, and has the capacity to understand concepts as relative rather than absolute. In formal operations, a young adult is able to discern the underlying motivations or principles of something (such as an idea, a theory, or an action) and can apply them to novel situations.

Lawrence Kohlberg

Lawrence Kohlberg (1927-1987) elaborated on Piaget’s work on moral reasoning and cognitive development, and identified a stage theory of moral thinking that is based on the idea that cognitive maturation affects reasoning about moral dilemmas. Kohlberg described six stages of moral reasoning, determined by a person’s thought process, rather than the moral conclusions the person reaches.7 He presented a person with a moral dilemma and studied the person’s response; the most famous dilemma involved Heinz, a poor man whose wife was dying of cancer. A pharmacist had the only cure, and the drug cost more money than Heinz would ever have.

Heinz went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he could only get together about half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said “No.” The husband got desperate and broke into the man’s store to steal the drug for his wife. Should the husband have done that? Why?7

Kohlberg is not without his critics, who view his schema as Western, predominantly male, and hierarchical. For example, in many non-Western ethnic groups the good of the family or the well-being of the community takes moral precedence over all other considerations.8 Such groups would not score well at Kohlberg’s post-conventional level. Another critic, Carol Gilligan, sees Kohlberg’s stages as biased against women. She believed that Kohlberg did not take into account the gender differences of how men and woman make moral judgments, and as such, his conception of morality leaves out the female voice.9 She has viewed female morality as placing a higher value on interpersonal relationships, compassion, and caring for others than on rules and rights. However, despite important differences between how men and women might respond when presented with an ethical dilemma, research has shown that there is not a significant moral divide between the genders.10

Attachment Theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth

Bowlby argued that human infants are born with a powerful, evolutionarily derived drive to connect with the mother.11 Infants exhibit attachment behaviors (such as smiling, sucking, and crying) that facilitate the child’s connection to the mother. The child is predisposed to psychopathology if there are difficulties in forming a secure attachment, for example, in a mother with severe mental illness, or there are disruptions in attachment (such as prolonged separation from the mother). Bowlby described three stages of behavior in children who are separated from their mother for an extended period of time.12 First, the child will protest by calling or crying out. Then the child exhibits signs of despair, in which he or she appears to give up hope of the mother’s return. Finally, the child enters a state of detachment, appearing to have emotionally separated himself or herself from the mother and initially appearing indifferent to her if she returns.

Mary Ainsworth (1913–1999) studied under Bowlby and expanded on his theory of attachment. She developed a research protocol called the strange situation, in which an infant is left alone with a stranger in a room briefly vacated by the mother.13 By closely observing the infant’s behavior during both the separation and the reunion in this protocol, Ainsworth was able to further describe the nature of attachment in young children. Based on her observations, she categorized the attachment relationships in her subjects as secure or insecure. Insecure attachments were further divided into the categories of insecure-avoidant, insecure-resistant, and insecure-disorganized/disoriented. Trained raters can consistently and reliably classify an infant’s attachments into these categories based on specific, objective patterns of behavior. Ainsworth found that approximately 65% of infants in a middle-class sample had secure attachments by 24 months of age.

BRAIN DEVELOPMENT

The mature human brain is believed to have at least 100 billion cells. Neurons and glial cells derive from the neural plate, and during gestation new neurons are being generated at the rate of about 250,000 per minute.14 Once they are made, these cells migrate, differentiate, and then establish connections to other neurons. Brain development occurs in stages, and each stage is dependent on the stage that comes before. Any disruption in this process can result in abnormal development, which may or may not have clinical relevance. It is believed that disruptions that occur in the early stages of brain development are linked to more significant pathologyy and those that occur later are associated with less diffuse problems.15

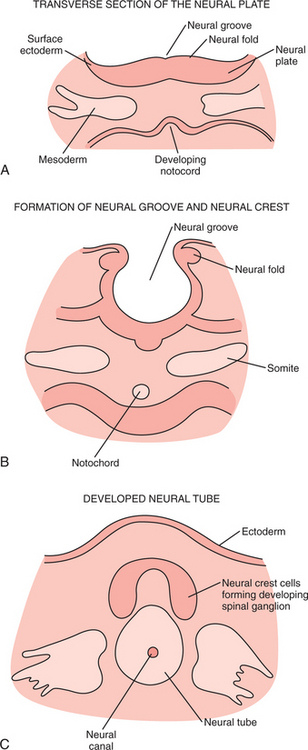

By around day 20 of gestation, primitive cell layers have organized to form the neural plate, which is a thickened mass comprised primarily of ectoderm. Cells are induced to form neural ectoderm in a complicated series of interactions between them. The neural plate continues to thicken and fold, and by the end of week 3 the neural tube (the basis of the nervous system) has formed (Figure 5-1).16

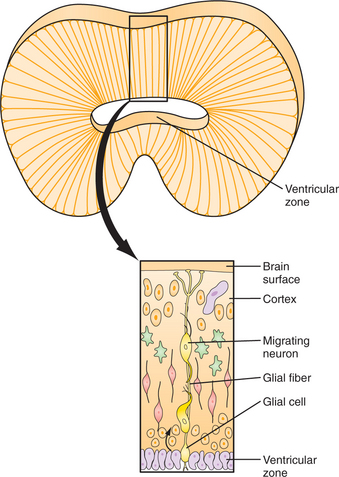

The neuroepithelial cells that make up the neural tube are the precursors of all central nervous system (CNS) cells, including neurons and glial cells. As the embryo continues to develop, cells of the CNS differentiate, proliferate, and migrate. Differentiation is the process whereby a primitive cell gains specific biochemical and anatomical function. Proliferation is the rapid cellular division (mitosis) that occurs near the inner edge of the neural tube wall (ventricular zone) and is followed by migration of these cells to their “correct” location. As primitive neuroblasts move out toward the external border of the thickening neural tube, this “trip” becomes longer and more complicated. This migration results in six cellular layers of cerebral cortex, and each group of migrating cells must pass through the layers that formed previously (Figure 5-2). It is believed that alterations in this process can result in abnormal neurodevelopment, such as a finding at autopsy of abnormal cortical layering in the brains of some patients with schizophrenia.17

Postnatal brain development is a period of both continued cellular growth and fine-tuning the established brain circuitry with processes of cellular regression (including apoptosis and pruning).15 While the human brain continues to grow and to mature into the mid-twenties, the brain at birth weighs approximately 10% of the newborn’s body weight, compared to the adult brain, which is about 2% of body weight. This growth is due to dendritic growth, myelination, and glial cell growth.

There are “critical periods” of development when the brain requires certain environmental input to develop normally. For example, at age 2 to 3 months there is prominent metabolic activity in the visual and parietal cortex, which corresponds with the development of an infant’s ability to integrate visual-spatial stimuli (such as the ability to follow an object with one’s eyes). If the baby’s visual cortex is not stimulated, this circuitry will not be well established. Synaptic growth continues rapidly during the first year of life, and is followed by pruning of unused connections (a process that ends sometime during puberty).

Newer imaging techniques have made it possible to continue to study patterns of brain development into young adulthood. In one longitudinal study of 145 children and adolescents, it was found that there is a second period of synaptogenesis (primarily in the frontal lobe) just before puberty that results in a thickening of gray matter followed by further pruning.18 Perhaps this is related to the development of executive-function skills noted during adolescence. In another study, researchers found that white matter growth begins at the front of the brain in early childhood and moves caudally, and subsides after puberty. Spurts of growth from ages 6 to 13 were seen in the temporal and parietal lobes and then dropped off sharply, which may correlate with the critical period for language development.19

Social and emotional experiences help contribute to normal brain development from a young age and continue through adulthood. Environmental input can shape neuronal connections that are responsible for processes (e.g., memory, emotion, and self-awareness).20 The limbic system, hippocampus, and amygdala continue to develop during infancy, childhood, and adolescence. The final part of the brain to mature is the prefrontal cortex, and adulthood is marked by continued refinement of knowledge and learned abilities, as well as by executive function and by abstract thinking.

Infancy (Birth to 18 Months)

Winnicott famously remarked, “There is no such thing as a baby. There is only a mother and a baby.”21 In this statement, we are reminded that infants are wholly dependent on their caretakers in meeting their physical and psychological needs. At birth, the infant’s sensory systems are incompletely developed and the motor system is characterized by the dominance of primitive reflexes. Because the cerebellum is not fully formed until 1 year of age, and myelination of peripheral nerves is not complete until after 2 years of age, the newborn infant has little capacity for voluntary, purposeful movement. However, the infant is born with hard-wired mechanisms for survival that are focused on the interaction with the mother. For instance, newborns show a visual preference for faces and will turn preferentially toward familiar or female voices. The rooting reflex, in which the infant turns toward stimulation of the cheek or lips, the sucking reflex, and the coordination of sucking and swallowing allow most neonates to nurse successfully soon after birth. Though nearsighted, a focal length of 8 to 12 inches allows the neonate to gaze at the mother’s face while nursing. This shared gaze between infant and mother is one of the early steps in the process of attachment.

Temperament

Infants demonstrate significant variability in their characteristic patterns of behavior and their ways of responding to the environment. Some of these characteristics appear to be inborn, in that they can be observed at an early age and remain fairly constant throughout the life span. The work of Stella Chess and Alexander Thomas in the New York Longitudinal Study helped capture this variability in their description of temperament.22 Temperament, as defined by Chess and Thomas, refers to individual differences in physiological responses to the environment. Chess and Thomas described nine behavioral dimensions of temperament, as outlined in Table 5-2.

| Activity Level | The level of motor activity demonstrated by the child and the proportion of active to inactive time |

| Rhythmicity | The regularity of timing in the child’s biological functions such as eating and sleeping |

| Approach or Withdrawal | The nature of the child’s initial response to a new situation or stimulus |

| Adaptability | The child’s long-term (as opposed to initial) response to new situations |

| Threshold of Responsiveness | The intensity level required of a stimulus to evoke a response from the child |

| Intensity of Reaction | The energy level of a child’s response |

| Quality of Mood | The general emotional quality of the child’s behavior, as measured by the amount of pleasant, joyful, or friendly behavior versus unpleasant, crying, or unfriendly behavior |

| Distractibility | The effect of extraneous stimuli in interfering with or changing the direction of the child’s activity |

| Attention Span and Persistence | The length of time the child pursues a particular activity without interruption and the child’s persistence in continuing an activity despite obstacles |

Chess and Thomas hypothesized that different parenting styles would be optimal for children of different temperaments.23 They coined the term goodness of fit to describe the degree to which an individual child’s environment is compatible with the child’s temperament in a way that allows the child to achieve his or her potential and to develop healthy self-esteem. When the child’s temperament is not accommodated, there is a poorness of fit that may lead to negative self-evaluation and to emotional problems later in life.

Motor Development in Infancy

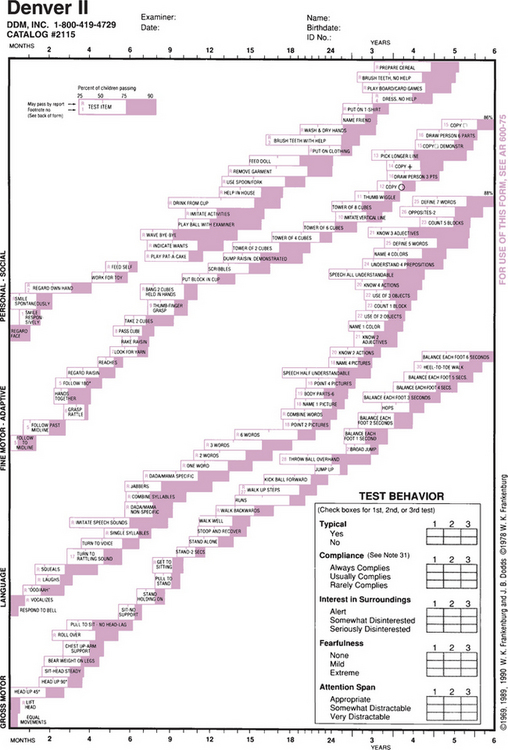

The tonic neck reflex, in which turning the newborn’s head to one side produces involuntary extension of the limbs on the same side and flexion of the limbs on the opposite side, begins to fade at 4 months of age, giving way to more symmetrical posture and clearing the way for continued gross motor development. The infant begins to show increasing head control at 1 to 2 months, and increased truncal control allows the infant to roll from front to back around 4 months of age. However, in recent years, with infants spending less time on their stomachs (in large part due to the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations that infants sleep on their backs), the typical development of rolling occurs closer to 6 months of age. The ability to sit without support develops at 6 months. Many infants begin to crawl around 8 months of age and can pull to stand around 9 months. Cruising, walking while holding onto objects (such as coffee tables and chairs), precedes independent walking, which begins around 12 months of age. Major developmental milestones are illustrated in Figure 5-3, the Denver II Developmental Assessment.24

Cognitive Development in Infancy

In Piaget’s theory, described previously, the infant progresses through the sensorimotor stage in the first 2 years of life.6 During this time, the infant learns about himself or herself and the external environment through sensory input and uses developing motor skills to learn to manipulate the environment. A major milestone during this stage is the development between 9 and 12 months of object permanence, in which the infant gradually realizes that objects continue to exist when they cannot be seen. Before this stage, infants will quickly give up looking for an object that has been dropped if it is not seen. Following the development of object permanence, an infant will look for a toy that had been visible to the infant and is now hidden under a blanket.

Language Development in Infancy

Communication in the first months of life is achieved through nonverbal means. However, the infant is attuned to language at birth. Newborns have been shown to preferentially attend to human voices. There is some evidence that even in utero the fetus shows a stronger response to the mother’s voice compared to the voices of other females.25 By 6 months infants can detect phonetic differences in speech sounds that are played to them. At 9 months, infants begin to demonstrate comprehension of individual words. By 13 months, they have a receptive vocabulary of approximately 20 to 100 words.

Social and Emotional Development in Infancy

Once a young child’s motor skills have developed sufficiently, the child begins to use his or her newfound mobility to explore the environment. In Mahler’s theory of separation-individuation, this phase of exploration is called the practicing subphase, which corresponds to roughly 10 to 16 months of age.26 Early in this stage, the child experiences a mood of elation as he or she develops a sense of self and his or her abilities. However, these early explorations are characterized by the need to frequently reestablish contact with the mother, which may be achieved physically (by returning to her), visually (by seeking eye contact), or verbally (by calling out to her). This contact with the mother allows the child to regain the sense of security that he or she needs to continue explorations. The degree to which the child seeks out the mother during this phase is variable and dependent on the child’s individual temperament.

Many children will identify a transitional object to help soothe them during the process of separating from the parents. This frequently occurs around 1 year of age and generally takes the form of a soft object (such as a blanket or stuffed animal) that has some association with the mother. Winnicott hypothesized that such objects provide a physical reminder of the mother’s presence before the child has fully developed an internal representation of the mother and the ability to separate without anxiety.27 Most children will surrender their transitional object by age 5, though there is considerable variability in children’s behavior in this area.

Preschool Years (2½ to 5 Years)

Cognitive Development in the Preschool Years

Cognitive development in the preschool years is characterized by increasing symbolic thought. In Piaget’s model, age 2 marks the end of the sensorimotor stage of development and the beginning of the preoperational stage.6 During this stage, children show an increase in the use of mental representations in their thinking. They learn to represent an object or idea with a symbol, such as a drawing, a mental image, or a word. The growth of symbolic thinking is evident in the preschooler’s increased use of language, imaginary play, and drawing.

Language Development in the Preschool Years

Language development in the preschool years is highly variable, with a broad range of abilities that could be considered normal. Development is largely influenced by environmental influences, such as the amount of speech to which the child is exposed and the degree to which adults in the child’s environment engage the child linguistically using questions, description, and encouragement of the child’s efforts toward expressing himself or herself.28

Problems in language development usually occur during this time of rapid acquisition of language.28 Stuttering affects up to 3% of preschool-age children. While this problem usually resolves on its own, prolonged or severe stuttering may require referral to a speech therapist for treatment.29

Social and Emotional Development in the Preschool Years

Theory of mind is a term used to indicate the child’s capacity to represent and to reflect on the feelings and mental states of others. Important steps in the development of a child’s theory of mind occur between 3½ and 5 years of age. At age 3, the typical child has difficulty understanding that other people have mental states that are distinct from his or her own. This can be demonstrated in a paradigm called the false-belief task, described by Wimmer and Perner.30 In this paradigm, the child is presented with a story in which a character has a mistaken belief about the location of an object, and the child is asked to predict where the character will look for that object. To answer correctly on the false-belief task, a child must be able to assume the perspective of a character in the story. Between ages 3½ and 5, children’s performance on this task improves as they are increasingly able to represent the mental states of others and accurately predict behavior on this basis. This capacity to appreciate the perspective of others allows for the development of more complex social interactions, empathy, and cooperation regarding the needs and feelings of others.

School-Age Years (5 to 12 Years)

As a child grows from preschool-age to school-age, the developmental challenges become more varied and complex. The child’s world expands beyond the primarily home-centered environment to other, more social arenas (such as nursery school and kindergarten), activities such as Cub Scouts or gymnastics, and play dates with peers. The preschooler matures from the egocentric toddler to a young child with the capacity to think logically, to empathize with others, and to exercise self-control. The child’s cognitive style gradually evolves from magical thinking to one based more in logic, with an ability to understand cause and effect and to distinguish between fantasy and reality. As a child becomes more autonomous, peer relationships begin to play an increasingly important role in the young child’s social and emotional development. Maturation (including increasing language acquisition, improved motor skills, continued cognitive growth, and the capacity for self-regulation) help equip the preschool-age child for these challenges.

Language Development in the School-age Years

By age 7, a child has a basic grasp of grammar and syntax. Unlike the preschool child, whose use of language is primarily based on specific concepts and rules, the school-age child begins to comprehend variations of those rules and various constructions. The child’s vocabulary continues to increase, although not as rapidly as during the preschool years. A child in this age-group is able to understand and manipulate semantics and enjoy word play; for example, in the Amelia Bedelia series of books, Amelia throws dirt on the family couch when she is asked to “dust the furniture.”31 Language becomes an increasingly effective means of self-expression as the school-age child is able to tell a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end. This mastery of language and expression also helps young children modulate affect, as they can more readily understand and explain their frustrations.

Motor Development in the School-age Years

Steady physical growth continues into middle childhood, but at a slower rate than during early childhood. Boys are on average slightly larger than girls until around age 11, when girls are likely to have an earlier pubertal growth spurt.32 It can be a period of uneven growth, and some children may have an awkward appearance; however, for most children of this age there is a relatively low level of concern about their physical appearance (especially for boys.) However, both peers and the media can influence how a child feels about his or her body, and even prepubertal girls can begin to exhibit symptoms of eating disorders and body image distortions. Gross motor skills (such as riding a bicycle) continue to improve and to develop, and by around age 9 these skills do not require specific thought or concentration, but are instead performed with ease. In this age-group mastery of specific athletic skills may emerge and can be seen by peers and family alike as a measure of competence. For the child who is less proficient at these skills, this may be a source of stress or frustration.

Cognitive Development in the School-age Years

In middle childhood children will develop specific interests, hobbies, and skills. Children often will collect all kinds of objects, from sports cards to dolls to rocks. Hobbies might include making model cars or craft projects (such as sewing). Anna Freud suggested that hobbies are “halfway between work and play,” because they involve mental skills (such as categorization or the skill to build an object), yet are also expressions of fantasy.33

Social and Emotional Development in the School-age Years

In middle childhood, friendships and relationships with peers take on a larger significance. Children become concerned about the opinions of their classmates, and depend on their peers for companionship, as well as for validation and advice. Close bonds are often developed between same-gender peers, usually based on perceived common interests (which might include living in the same neighborhood). Children tend to pick best friends who share similar values and cultural boundaries; from ages 3 to 13, close friendships increasingly involve children of the same sex, age, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.34 Further, having a best friend who is not the same age or gender correlates with being rejected or ignored by one’s classmates.35

Moral Development in the School-age Years

Kohlberg described children of this age having achieved varying levels of moral development.7 Children continue to internalize societal norms, but the fear of punishment or earned reward that motivates the preschooler gives way to hope for approval or positive feedback from adults and peers. Some middle-schoolers adopt an inflexible acceptance of rules of behavior that are to be followed. A school-age child will often become fixated on concepts of right and wrong, and lawfulness; it would be typical, for example, for a 9-year-old child to point out to her carpool driver that she was driving above the speed limit. The middle-school child assimilates the values and norms of his or her parental figures and culture, and the result is a reasonably well-formed superego and conscience. The child gains mastery of cognitive skills (such as considering two variables at one time), and he or she will begin to appreciate other points of view. In games, he or she learns that rules are mutually agreed on and, in special circumstances, can be altered (“Since we only have three people, let’s play with four outs instead of three.”).

Adolescence (12 to 20 Years)

Physical Development during Adolescence

Puberty is the beginning of adolescence, and physical changes are accompanied by a heightened consciousness about one’s body and sexuality. It is a time of drastic physical change. In the United States, puberty begins for girls between ages 8 and 13 years with breast bud development and continues through menarche; for boys it begins around age 14 and is marked by testicular enlargement followed by growth of the penis.36 There are of course variations in these ages, and several factors can affect the timing of puberty and associated stages of growth, including health, weight, nutritional status, and ethnicity. For example, as a group, African American girls enter puberty earliest, followed by Mexican Americans and Caucasians.36

With the onset of puberty for both sexes there are periods of rapid gains in height and weight, and for boys, muscle mass. Similarly, hormonally mediated physical changes include increased sebaceous gland activity that can result in acne. Girls often experience a growth spurt up to 2 years earlier than boys.37 There can be an associated period of clumsiness or awkwardness, because linear limb growth may not be proportional to increased muscle mass. Furthermore, some girls experience the weight gain of puberty as problematic; in one study, 60% of adolescent girls reported that they were trying to lose weight. Physical development does not occur smoothly or at the same rate for all adolescents, and at a time when the desire to “fit in” and be “normal” is paramount, this can be a source of considerable stress.

Other physical changes that occur with early adolescence include an increased need for sleep (on average, teenagers need about 9½ hours of nightly sleep) and a shift in the sleep-wake cycle, such that they tend to stay up later and wake up later.38 Of course, with the demands of school and extracurricular activities, most adolescents do not get the amount of sleep they need. This can result in daytime sleepiness, which can in turn impair motor function and cognitive performance.

Cognitive Development during Adolescence

By mid-adolescence, most teenagers have developed the capacity for abstract thinking. Piaget termed this stage as formal operations, where a person can evaluate and manipulate the data and emotions in his or her environment in a constructive manner, using his or her experience, as well as abstract thought.6 The capacity to think abstractly, that is, to be able to consider an idea in a hypothetical, “what if” manner, is the hallmark of formal operations. This skill enables adolescents to navigate more complicated situations and to comprehend more complex ideas.

Moral Development during Adolescence

An adolescent’s moral principles mirror the primary developmental task of this age, namely, to separate oneself from dependence on caregivers and family. In late childhood, maintaining the rules of the group has become a value; during adolescence there is a move toward an autonomous moral code that has validity with both authority and the individual’s own beliefs of what is right and wrong. Teenagers often “test” their parents’ moral code. Role models are important, and while younger children might choose them for their superhuman powers, the early adolescent selects his or her heroes based on realistic and hoped-for ideals, talents, and values.

Sexual Development during Adolescence

The task of mid-adolescence is to manage a likely strong sexual drive with peer and cultural expectations. Sexual activity in and of itself is value-neutral and developmentally normal. In several industrialized countries, the age at first sexual intercourse has become increasingly younger over the past two decades. In one study, 45% of high school students acknowledged being sexually active.39 Most mid-adolescents engage in some kind of sexual activity, the extent of which depends on factors including cultural influences and socioeconomic status. For example, black and socioeconomically disadvantaged youth are more likely to be sexually active.40

Adult Development

Young Adulthood

Development does not cease with the end of adolescence. Young adulthood (generally defined as ages 20 to 30) presents challenges and responsibilities, which are not necessarily based on chronological age. Contemporary adult theorists, such as Daniel Levinson and George Vaillant, describe adult growth as periods of transition in response to mastering adult tasks, in contrast to the specific stages used to summarize child development.41,42 The transition from adolescence to young adulthood is marked by specific developmental challenges including leaving home, redefining the relationship with one’s parents, searching for a satisfying career identity, and sustaining meaningful friendships. This is also a period when a young person develops the capacity to form more intimate relationships and will likely find a life partner.

Growth in the young adult is less a physical phenomenon and more one of a synthesis of physical, cognitive, and emotional maturity. Linear growth is replaced by adaptation and reorganization of processes that are already present. Young adulthood is described by roles and status (such as employment or parenthood), and there are a variety of developmental pathways, which are affected by factors including culture, gender, and historical trends.43 For example, in 1999 in the United States the mean age for mothers at the birth of the first child was 24.8 years and 29.7 years for fathers44; in the nineteenth century, it was common for teenagers to run a household and begin to raise a family. The trajectory of young adult growth is as much a function of the environment as continued biological growth.

There is significant variability in the transitions for young adults as they complete their high school education. Of Americans between ages 18 and 24, just under 50% are enrolled in secondary education programs or have completed college. Many young adults move away from their parents’ homes as they enter the workforce or college. Such “cutting of the apron strings” can be a stressful period for the young adult, who may have yet to fully establish a stable home or social environment.

Middle to Late Adulthood

While there are no specific physical markers of moving from young adulthood to midlife, this is a period when maturation begins to give way to aging. The human body begins to slow, and how well one functions becomes more sensitive to diet (including substance use), exercise, stress, and rest. This is often a period when chronic health problems become more problematic, or when good health may be threatened by disease or disability. Bones may lose mass and density (made more complicated by a woman’s estrogen loss as she nears menopause), and vertebral compression along with loss of muscle results in a slight loss of height. After age 40, the average person loses approximately 1 cm of height every 10 years.45 Responses to this aging process vary from person to person, but experiencing a sense of loss or sadness around these changes is not uncommon.

Late Adulthood and Senescence

The average life expectancy for a person living in the United States is 77.9 years.46 By 2030, it is projected that half of all Americans will be over age 65. While it seems counterintuitive to consider “old age” as part of development, there are specific developmental tasks to be achieved. These include accepting physical decline and limitations, adjusting to retirement and possibly a lower income, maintaining interests and activities, and sharing one’s wisdom and experiences with families and friends. Another challenge is to accept the idea that one may become increasingly dependent on others, and that death is inevitable.

1 Freud S Three essays on the theory of sexuality: the standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud;vol 7; 1905, Hogarth Press London.

2 Freud S. Beyond the pleasure principle. New York: WW Norton & Company, 1961.

3 Freud S. An outline of psycho-analysis. New York: WW Norton & Company, 1969.

4 Erikson EH. Childhood and society, ed 2. New York: WW Norton & Company, 1963.

5 Piaget J. Judgment and reasoning in the child. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1928.

6 Piaget J, Inhelder B. The psychology of the child. New York: Basic Books, 1969.

7 Kohlberg L. Stage and sequence: the cognitive-developmental approach to socialization. In: Goslin DA, editor. Handbook of socialization theory and research. New York: Rand McNally, 1969.

8 Wainryb C, Turiel E. Diversity in social development: between or within cultures? In: Killen M, Hart D, editors. Morality in everyday life: developmental perspectives. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

9 Gilligan C. In a differen psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982.

10 Walker LJ. The development of moral reasoning. Ann Child Dev. 1988;55:677-691.

11 Bowlby J Attachment: attachment and loss series;vol 1; 1969, Basic Books New York.

12 Bowlby J Separation: attachment and loss series;vol 2; 1973, Basic Books New York.

13 Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns o a psychological study of the strange situation. Oxford, England: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1978.

14 Cowan WM. The development of the brain. Sci Am. 1979;241(3):113-133.

15 Steingard RJ, Schmidt C, Coyle JT. Basic neuroscience: critical issues for understanding psychiatric disorders. Adolesc Med. 1998;9(2):205-215.

16 O’Rahilly R, Muller F. Neurulation in the normal human embryo. Ciba Found Symp. 1994;181:70-82.

17 Benes FM. The relationship between structural brain imaging and histopathologic findings in schizophrenia research. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 1993;1(2):100-109.

18 Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, et al. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(10):861-863.

19 Thompson PM, Giedd JN, Woods RP, et al. Growth patterns in the developing brain detected by using continuum mechanical tensor maps. Nature. 2000;404(6774):190-193.

20 Siegel DJ. Thmind: toward a neurobiology of interpersonal experience. New York: Guilford, 1999.

21 Winnicott DW. The child, the family, and the outside world. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1987.

22 Thomas A, Chess S. Temperament and development. New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1977.

23 Chess S, Thomas A. Origins and evolution odisorders from infancy to early adult life. New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1984.

24 Frankenburg WE, Dodds JB. The Denver developmental assessment (Denver II). Denver: University of Colorado Medical School, 1990.

25 Kisilevsky BS, Hains SM, Lee K, et al. Effects of experience on fetal voice recognition. Psychol Sci. 2003;14(3):220-224.

26 Mahler MS, Pine F, Bergmann A. The psychological birth of the human infant. New York: Basic Books, 1975.

27 Winnicott DW. Transitional objects and transitional phenomena (1951). In Collected papers. London: Tavistock; 1958.

28 Toppelberg CO, Shapiro T. Language disorders: a 10-year research update review. J Am Acad Child and Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(2):143-152.

29 Craig A, Hancock K, Tran Y, et al. Epidemiology of stuttering in the community across the entire life span. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2002;45(6):1097-1105.

30 Wimmer H, Perner J. Beliefs about beliefs: representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition. 1983;13:41-68.

31 Parish P. Amelia Bedelia. New York: Harpercollins, Juvenile Books, 1963.

32 Tanner JM, Davies PSW. Clinical longitudinal standards for height and weight velocity for North American children. Pediatrics. 1985;107:317-329.

33 Freud A. Normality and pathology in childhood: assessments of development. New York: International Universities Press, 1965.

34 Aboud FE, Mendelson MJ. Determinants of friendship selection and quality: developmental perspectives. In: Bukowski WM, Newcomb AR, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: friendship in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

35 Kovacs DM, Parker JG, Hoffman LW. Behavioral, affective, and social correlates of involvement in cross-sex friendships in elementary school. Child Dev. 1996;67:2269-2286.

36 Kaplowitz PB, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC, et al. Earlier onset of puberty in girls: relationship to increased body mass index and race. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):347-353.

37 Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the patterns of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:13-23.

38 Neinstein LS, editor. Adolescent health care: a practical guide, ed 4, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

39 Barone C, Ickovics JR, Ayers TS, et al. High-risk sexual behavior among young urban students. Fam Plann Perspect. 1996;28(2):69-74.

40 Warren CW, Santelli JS, Everett SA, et al. Sexual behavior among US high school students, 1990-1995. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30(4):170-172.

41 Levinson DJ, Darrow CM, Klein EB, et al. The seasons of a man’s life. New York: Knopf, 1978.

42 Vaillant GE. Adaptation to life. Boston: Little, Brown, 1977.

43 Hogan DP, Astone NM. The transition to adulthood. Annu Rev Sociol. 1986;12:109-130.

44 Ventura SJ, Martin JA, Curtin SC, et al Births: final data for 1999;vol 49; 2001, National Center for Health Statistics Hyattsville, MD.

45 United States National Library of Medicine: National Institutes of Health, www.nlm.nih.gov (accessed January 11, 2007).

46 Minino AM, Heron M, Smith BL: Deaths: preliminary data for 2004, www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/prelimdeaths04/preliminarydeaths04.htm (accessed January 11, 2007).