CASE 49 Aortic Balloon Valvuloplasty

Cardiac catheterization

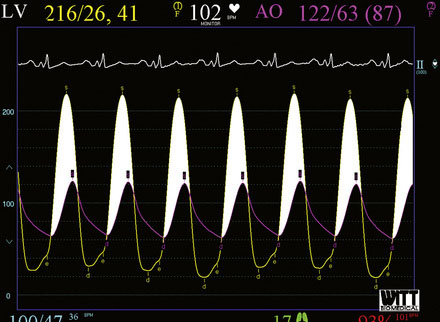

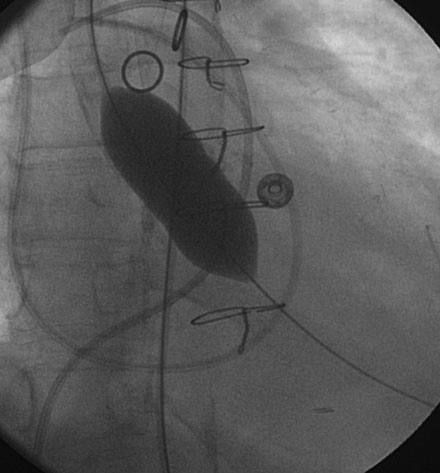

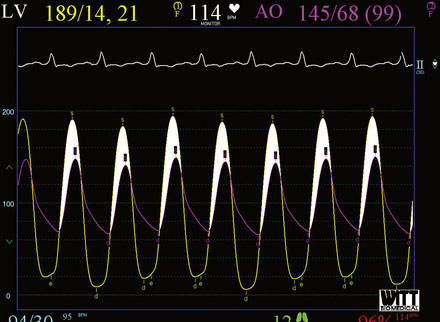

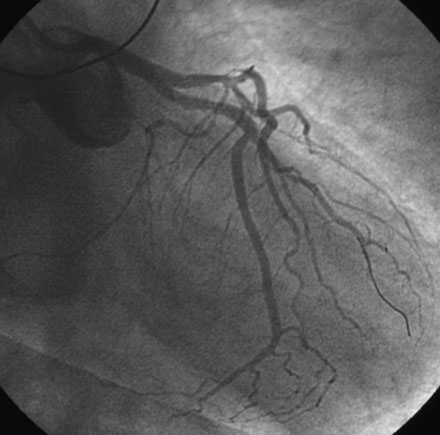

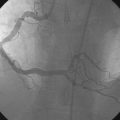

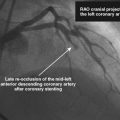

Cardiac catheterization consisted only of a hemodynamic study in order to avoid worsening renal function from exposure to iodinated contrast agents. Her baseline hemodynamics revealed severe heart failure with a mean right atrial pressure of 11 mmHg, a pulmonary artery pressure of 53/27 mmHg and a mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 33 mmHg. The cardiac output was 4.8 L/minute. Using a straight wire to cross the aortic valve, the operator placed a dual-lumen pigtail catheter into the left ventricle and measured a baseline peak-to-peak systolic gradient across the aortic valve of 94 mmHg, yielding a calculated valve area of 0.7 cm2 (Figure 49-1). An extra-stiff, 0.038 inch Amplatz guidewire was advanced through the pigtail catheter into the left ventricle and the pigtail catheter removed. The originally inserted 6 French arterial sheath was replaced with a 12 French sheath, and a 5 cm long by 18 mm diameter valvuloplasty balloon was advanced and centered across the aortic valve. Using a 30-cc syringe filled with dilute contrast, the balloon was inflated by hand (Figure 49-2 and Video 49-1). The balloon was deflated and removed over the guidewire and replaced with the dual lumen pigtail catheter. The operator noted that the transaortic peak-to-peak systolic pressure gradient only diminished by 20 mmHg. Thus, a 5 cm long by 22 mm diameter balloon was advanced, centered across the aortic valve, and inflated. The transaortic pressure gradient after the second balloon inflation is shown in Figure 49-3, with the peak-to-peak systolic gradient noted to fall to 44 mmHg, yielding a valve area of 1.1 cm2.

Discussion

Aortic balloon valvuloplasty is an effective method to treat congenital aortic stenosis, but its efficacy in calcific aortic stenosis is limited. Original reports from the 1980s confirmed its role primarily as a palliative procedure. In one series of 170 patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing balloon valvuloplasty, the peak transaortic gradient fell from about 70 mmHg to 36 mmHg with the valve area increasing from an average of 0.6 to 0.9 cm2.1 Thus, patients are still left with significant aortic stenosis and, although symptoms typically improve, the restenosis rate is very high, with at least 50% of patients experiencing restenosis within 6 to 12 months. Importantly, aortic balloon valvuloplasty does not improve long-term survival, which remains very poor and not different from the expected survival for untreated severe aortic stenosis.2,3 For these reasons, aortic balloon valvuloplasty is recommended as a Class IIb indication only as a bridge to aortic valve surgery in hemodynamically unstable patients (i.e., severe heart failure or shock) with severe aortic stenosis at high risk for emergency aortic valve surgery or as a palliative procedure in a patient with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis who is not an operative candidate.4 The procedure was chosen for the patient presented in this case because she was felt to be unsuitable for an emergent heart operation due to progressive renal failure and refractory pulmonary edema. The goal of the procedure was to improve her hemodynamic status such that her renal failure and heart failure would improve to a point that valve replacement surgery could proceed at a much lower risk. The procedure resulted in the usual and expected degree of hemodynamic improvement and initially, clearly improved her clinical status. Unfortunately, her comorbid illnesses, particularly her renal failure, exacerbated her condition, precluding her candidacy for aortic valve surgery and she succumbed to the disease.

The usual procedural technique is described in this case. The retrograde approach is fairly simple, but requires up to a 12 French sheath; this may be an issue in patients with peripheral vascular disease. An alternative is to position the balloon anterograde across the aortic valve via a transseptal puncture, using an Inoue balloon.5 This approach requires a great deal of skill but can reduce the risk of vascular complication. When the retrograde approach is used, it may prove difficult to position the balloon during inflations because of the tendency to “spit” or “watermelon seed.” Brief bursts of rapid ventricular pacing at ventricular rates of 180 to 200 beats per minute can be employed to transiently lower the cardiac output and allow the balloon to inflate without movement.

1. Safian R.D., Berman A.D., Diver D.J., McKay L.L., Come P.C., Riley M.F., Warren S.E., Cunningham M.J., Wyman M., Weinstein J.S., Grossman W., McKay R.G. Balloon aortic valvuloplasty in 170 consecutive patients. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:125-130.

2. Otto C.M., Mickel M.C., Kennedy J.W., Alderman E.L., Bashore T.M., Block P.C., Brinker J.A., Diver D., Ferguson J., Holmet D.R. Three-year outcome after balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Insights into prognosis of valvular aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1994;89:642-650.

3. Lieberman E.B., Bashore T.M., Hermiller J.B., Wilson J.S., Pieper K.S., Keeler G.P., Pierce C.H., Kisslo K.B., Harrison J.K., Davidson C.J. Balloon aortic valvuloplasty in adults: failure of procedure to improve long-term survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1522-1528.

4. Bonow R.O., Carabello B.A., Chatterjee K., de Leon A.C.Jr, Faxon D.P., Freed M.D., Gaasch W.H., Lytle B.W., Nishimura R.A., O’Gara P.T., O’Rourke R.A., Otto C.M., Shah P.M., Shanewise J.S. 2008 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:e1-e142.

5. Sakata Y., Syed Z., Salinger M.H., Feldman T. Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty: antegrade transseptal vs. conventional retrograde transarterial approach. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;64(3):314-321.