CHAPTER 48

Low Back Strain or Sprain

Omar El Abd, MD; Joao E.D. Amadera, MD, PhD

Definition

Lumbar strain or sprain is a term used by clinicians to describe an episode of acute low back pain. The patients report pain in the low back at the lumbosacral region accompanied by contraction of the paraspinal muscles (hence, the expression “muscle sprain” or “strain”). The definite cause is unknown in most cases. It most likely is secondary to a chemical or mechanical irritation of the sensory nociceptive fibers in the intervertebral discs, facet joints, sacroiliac joints, or muscles and ligaments at the lumbosacral junction area.

Low back pain is a prevalent condition associated with work absenteeism, disability, and large health care costs [1]. Episodes of low back pain constitute the second leading symptom prompting patients to seek evaluation by a physician [2]. It is estimated that 50% to 80% of adults experience at least one episode of acute low back pain in their lives [3,4]. The incidence of radiculopathy is reported to be much lower than the incidence of axial back pain at 2% to 6% [5]. Patients who experience acute back pain usually see improvements and are able to return to work within a month [6,7]. However, 2% to 7% of patients have chronic back pain [8,9]. Several studies suggest that 90% of patients with an acute episode of low back pain recover within 6 weeks [10–12]. In contrast, some well-conducted cohort studies demonstrate a less optimistic picture, providing short-term estimates of recovery ranging from 39% to 76% [13,14]. Pengel and colleagues [6] published a meta-analysis investigating the course of acute low back pain, concluding that both pain and disability improve rapidly within weeks (58% reduction of initial scores in the first month) and recurrences are common. On the other hand, more recently, Menezes and associates [1] demonstrated that the typical course of acute low back pain is initially favorable, with a marked reduction in mean pain and disability in the first 6 weeks. After 6 weeks, improvement slows, and only small reductions in mean pain and disability are apparent for up to 1 year. By 1 year, the average measures of pain and disability for acute low back pain were very low, suggesting that patients can expect to have minimal pain or disability at 1 year.

Clinicians encounter a number of patients who convert from acute pain to chronic pain. In a recent review involving 10 studies and more than 4000 participants, Hallegraef and coworkers [15] investigated adults with acute and subacute nonspecific low back pain. The odds that patients with negative recovery expectations will remain absent from work because of progression to chronic low back pain was two times greater than for those with more positive expectations.

Consequently, the goals of the clinician evaluating patients with an episode of acute low back pain are to have a working differential diagnosis of the condition and its etiology, to rule out radiculopathy or other serious medical causes, to have a rehabilitation plan that aims to prevent recurrence of this episode, to educate the patient about the pathologic process, and to formulate a management plan if the condition does not improve promptly.

Symptoms

The pain develops spontaneously or acutely after traumatic or strenuous events such as sports participation, repetitive bending, lifting, motor vehicle accidents, and falls. Pain is predominantly located in the lumbosacral area (axial) overlying the lumbar spinous processes and along the paraspinal muscles. There may be an association with pain in the lower extremities; however, the lower extremity pain is less intense than the low back pain. Pain is usually described as sharp and shooting in character accompanied by paraspinal muscle tightness.

Trunk rotation, sitting, and bending forward usually exacerbate pain. Lying down with application of modalities (heat or ice) usually mitigates it.

Red flags that require prompt medical response are outlined in Table 48.1.

Table 48.1

Red Flags

| Symptom | Concern |

| Pain in the lower extremities (including the buttocks) more than pain in the lower back | Radiculopathy |

| Weakness or sensory deficit in one or both lower extremities | Radiculopathy and the possibility of cauda equina syndrome (especially if there is bilateral involvement of the lower extremities) |

| Bowel or bladder changes; saddle anesthesia | Cauda equina |

| Severe pain in the low back, including pain while lying down | Malignant neoplasm |

| Fever, chills, night sweats, recent loss of weight | Infection and malignant neoplasm |

| Injury related to a fall from a height or motor vehicle crash in a young patient or from a minor fall or heavy lifting in a patient with osteoporosis or possible osteoporosis | Fracture |

| History of cancer metastatic to bone | Malignant neoplasm |

Etiology

Axial Pain (Pain Overlying the Lumbosacral Area)

Discogenic pain due to degenerative disc disease is the most common known cause of axial pain. The pain from the intervertebral discs is located in proximity to the degenerated disc. Multiple inflammatory products are found in the painful disc tissue that may increase the excitability of the sensory neurons. The pain is referred from the disc to the surrounding paraspinal and pelvic girdle muscles.

Facet (zygapophyseal) joint arthropathy is another source of axial pain, present in about 30% to 50% of patients describing axial pain in the lumbar as well as in the cervical spine [16–18]. The facets are paired synovial joints adjacent to the neural arches. Pain is predominantly in the paraspinal area and is accompanied by contractions of the muscles that guard around the facet joints. The pain from the facet joints can be unilateral or bilateral.

Sacroiliac joint arthropathy is a cause of axial back pain as well. The pain is located in the lumbosacral-buttock junction with referral to the lower extremity and to the groin area. Painful conditions of the sacroiliac joint are known to result from spondyloarthropathies, infection, malignant neoplasms, pregnancies, and trauma and even to occur spontaneously.

Radicular Pain

Predominant buttocks area pain is a common presentation of lumbar radicular pain. Nerve roots can be affected secondary to mechanical pressure and inflammation. Mechanical pressure is usually secondary to disc protrusion (herniation) or due to spinal stenosis. Disc herniations involve all age groups, with predominance in the young and middle aged. Spinal stenosis, on the other hand, predominantly affects the elderly; it is a combination of disc degeneration, ligamentum hypertrophy, and facet arthropathy or spondylolisthesis. In radiculopathy, symptoms are present along a nerve root distribution. Sensory symptoms include pain, numbness, and tingling that follow the distribution of a particular nerve root. The symptoms may be accompanied by motor weakness in a myotomal distribution. Diagnosis and treatment of radiculopathy are discussed in Chapter 47.

Myofascial Pain

There are different theories explaining muscular reasons for acute low back pain, but they remain unproved [19,20]. These theories include inflammation—failure at the myotendinous junction and the production of an inflammatory repair response; ischemia—postural abnormalities causing chronic muscle activation and ischemia; trigger points secondary to repetitive strain of muscles (this theory remains the most attractive) [20]; and muscle imbalance.

The currently most accepted theory for muscle pain is related to the myofascial pain syndrome, which is a common reported disorder in chronic conditions but can be present in the acute conditions as well [21]. It is characterized by myofascial trigger points—hard, palpable, discrete, localized nodules located within taut bands of skeletal muscle and painful on compression. An active myofascial trigger point is associated with spontaneous pain, in which pain is present without palpation. This spontaneous pain can be at the site of the myofascial trigger points or remote from it. The current diagnostic standard for myofascial pain is based on palpation for the presence of trigger points in a taut band of skeletal muscle and an associated symptom cluster that includes referred pain patterns [22]. Treatment of myofascial pain involves massage, needling of the myofascial trigger points (with or without anesthetic injections), acupuncture, and stretching [23].

Referred Pain

Musculoskeletal structures in proximity to the spine and organs in the abdomen and pelvis are potential sources of pain with referral to the spine and the paraspinal area.

Occult Lesions

These lesions may be manifested with axial or radicular symptoms or with both. Spine metastasis [24] and spine and paraspinal infections are considered a rare possibility. Skilled history taking and physical examination are necessary in diagnosis of these dangerous conditions.

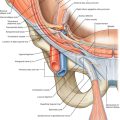

Physical Examination

The physical examination starts with a thorough history to ascertain the pain’s onset, character, location, and aggravating and mitigating factors. Inquiry about associated symptoms, such as weakness, bowel or bladder symptoms, fever, and abnormal loss of weight, and past medical history are important. Examination includes inspection of the lower back and the lower extremities. Palpation of the paraspinal muscles, lumbar facet joints, inguinal lymph nodes, and lower extremity pulses is performed. Hip examination, root tension signs, discogenic provocative maneuvers, and sacroiliac joint maneuvers are performed (Table 48.2). Gait examination, with heel and toe walking, is assessed. Sensory examination and thorough manual muscle testing are performed. Deep tendon reflexes are examined.

Table 48.2

Spine Physical Examination Maneuvers

| Maneuver | Description | Significance |

| Pelvic rock | In a supine position, flex the patient’s hips until the flexed knees approximate to the chest; then, rotate the lower extremities from one side to the other. | Lumbar discogenic pain provocation |

| Sustained hip flexion | In a supine position, raise the patient’s extended lower extremities to approximately 60 degrees. Ask the patient to hold the lower extremities in that position and release. The test result is positive on reproduction of low lumbar or buttock pain. Then lower the extremities successively approximately 15 degrees and, at each point, note the reproduction and intensity of pain. | Lumbar discogenic pain provocation |

| Root tension signs—upper extremity | Contralateral neck lateral bending and abduction of the ipsilateral upper extremity | Reproduces cervical radicular pain in the periscapular area or in the upper extremity |

| Spurling maneuver | Passively perform cervical extension, lateral bending toward the side of symptoms, and axial compression. | Reproduces cervical radicular pain in the periscapular area or in the upper extremity |

| Straight-leg raise | While the patient is lying supine, the involved lower extremity is passively flexed to 30 degrees with the knee in full extension. | Reproduces pain in the buttock, posterior thigh, and posterior calf in conditions with S1 radicular pain |

| Reverse straight-leg raise | While the patient is lying prone, the involved lower extremity is passively extended, the knee flexed. | Reproduces pain in the buttock and anterior thigh in conditions with high lumbar (such as L3 and L4) radicular pain |

| Crossed straight-leg raise | While the patient is lying supine, the contralateral lower extremity is passively flexed to 30 degrees with the knee in full extension. | Reproduces pain in the ipsilateral buttock, posterior thigh, and posterior calf in conditions with S1 radicular pain |

| Sitting root test | While the patient is sitting, the involved lower extremity is passively flexed with the knee extended. | Reproduces pain in the buttock, posterior thigh, and posterior calf in conditions with S1 radicular pain |

| Lasègue sign | While the patient is lying supine, the involved lower extremity is passively flexed to 90 degrees. | Reproduces pain in the buttock, posterior thigh, and posterior calf in conditions with S1 radicular pain |

| Bragard sign | While the patient is lying supine, the involved lower extremity is passively flexed to 30 degrees, with dorsiflexion of the foot. | Reproduces pain in the buttock, posterior thigh, and posterior calf in conditions with S1 radicular pain |

| Gaenslen maneuver | The patient is placed in a supine position with the affected side flush with the edge of the examination table. The hip and knee on the unaffected side are flexed, and the patient clasps the flexed knee to the chest. The examiner then applies pressure against the clasped knee, extends the lower extremity on the ipsilateral side, and brings it under the surface of the examination table. | Reproduces pain in patients with sacroiliac joint syndrome |

| Sacroiliac joint compression | Apply compression to the joint with the patient lying on the side. | Reproduces pain in patients with sacroiliac joint syndrome |

| Pressure at sacral sulcus | Apply pressure on the posterior superior iliac spine (dimple). | Reproduces pain in patients with sacroiliac joint syndrome |

| Patrick test (FABER test) | While the patient is supine, the knee and hip are flexed. The hip is abducted and externally rotated. | Reproduces pain in patients with sacroiliac joint syndrome, facet joint arthropathy (pain is reproduced in the low back), and degenerative joint disease of the hip (pain is reproduced in the groin) |

| Yeoman test | While the patient is in the prone position, the hip is extended and the ilium is externally rotated. | Reproduces pain in patients with sacroiliac joint syndrome |

| Iliac gapping test | Distraction can be performed to the anterior sacroiliac ligaments by applying pressure to the anterior superior iliac spines. | Reproduces pain in patients with sacroiliac joint syndrome |

Diagnostic Studies

Without clinical signs of serious disease, diagnostic imaging and laboratory testing are not required [25,26]. However, imaging is recommended in the presence of red flags (such as history of trauma, constitutional symptoms, suspicion of radiculopathy, history of cancer, or persistent symptoms lasting longer than 1 month without improvement), in rheumatologic conditions, with prolonged use of steroids, and in the case of litigations.

The “gold standard” for evaluation of painful spine conditions is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which allows good visualization of discs and nerves as well as provides valuable information necessary for further management if the condition does not improve. MRI evaluation is required only if symptoms persist for longer than 1 month or at the onset of radicular pain or weakness. It is also used in the workup for back pain accompanied by constitutional symptoms.

Treatment

Initial

Although there are numerous treatments for lumbar sprain and strain, most have little evidence of benefit. Inflammation is a major culprit of pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are a cornerstone of pain management and should be provided in adequate doses. The selective cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitors show fewer gastric side effects compared with traditional NSAIDs; however, studies have shown that COX-2 inhibitors are associated with increased cardiovascular risks in specific patient populations [27].

Muscle relaxants are beneficial [26] and commonly used for pain management along with NSAIDs. These medications do not target a particular pathologic process and should be used in conjunction with NSAIDs. They are particularly helpful in improving sleep and relieving muscle “spasms” or “tightness” in patients with low back pain. Tramadol and opioid medications can be used in cases of severe pain, but an association between early receipt of opioids for acute low back pain and poor outcomes such as need for surgery and risk of receiving late opioids was found in a large cohort study [28]. If there is a need for extended use of these medicines, imaging studies should be performed and other management modalities should be considered. Modalities such as heat and ice can also be used.

Bed rest is not recommended in management of acute low back pain. It is advisable to remain active as much as possible [29].

In a recent review, no substantial benefit was shown with oral steroids, acupuncture, massage, traction, lumbar supports, or regular exercise programs in management of acute low back pain. Manipulative therapy, such as spinal manipulation and chiropractic techniques, is no more effective than established medical treatments, and adding it to established treatments does not improve outcomes [26].

Rehabilitation

The cornerstone for a complete recovery and the prevention of a recurrence of lumbar strain or sprain or the transformation to chronic low back pain is participation in a regular spine stabilization program. The program should begin immediately after the pain starts to improve. Initiation of an exercise program while the patient is experiencing severe symptoms is not helpful because the patient’s ability to participate is limited by pain. Exercises directed by a physical therapist, such as spine stabilization exercises, may decrease recurrent pain and need for further health care services and expenses [30,31]. A lumbar stabilization exercise program consists of stretching the lower extremities, pelvis, and lumbosacral muscles as well as performing exercises to strengthen the lumbosacral muscles. Postural training and learning proper body mechanics are essential. Patients are taught to perform these exercises and are advised to incorporate them into their daily routine.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is widely used to treat patients with low back pain. A systematic review of the literature concluded that acupuncture is effective for pain relief and functional improvement in chronic back pain for a short term, but for acute back pain, no evidence of the effectiveness of acupuncture was found [32].

Procedures

Spinal injections are not considered a first-line management of acute low back pain. If progressive radiculopathy is suspected and the MRI study is consistent with this diagnosis, therapeutic spinal nerve root blocks should be promptly considered. In axial acute low back pain, if conservative management fails in 4 weeks, MRI is performed. If the MRI findings and the clinical findings suggest intervertebral disc disease, transforaminal epidural steroid injections or interlaminar epidural steroid injections are used. In this context, if MRI findings are unremarkable and pain persists, therapeutic facet joint injections or sacroiliac joint injections are used.

Surgery

Surgical intervention is not indicated in the management of acute low back pain without radiculopathy causing progressive neurologic deficits.

Potential Disease Complications

Most patients will recover within 2 weeks. However, if symptoms change from axial low back pain to radicular pain, weakness develops in one or both lower extremities, or pain persists, the clinician should promptly order imaging studies. Further management is required as soon as possible to prevent deterioration of the patient’s condition.

Potential Treatment Complications

Traditional NSAIDs used in management have resulted in gastrointestinal complications, such as peptic ulcer disease. Patients must take the medications with food, antacids, or ulcer-preventing medications. COX-2 inhibitors are associated with increased cardiovascular risks and should be taken for only short periods.

Muscle relaxants, tramadol, and opioids have sedative side effects. Patients are advised to refrain from driving and operating machinery while taking these medications.