CASE 48 Alcohol Septal Ablation for Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy

Cardiac catheterization

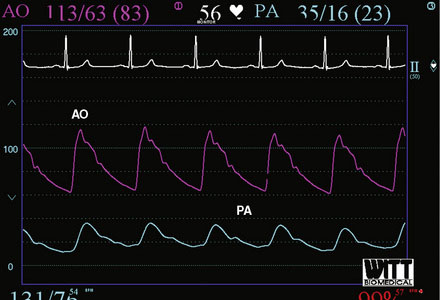

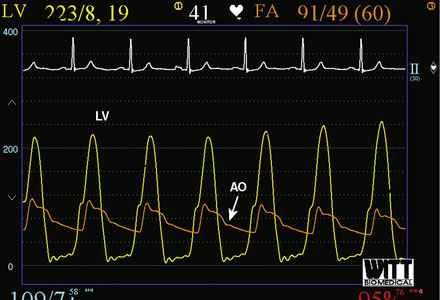

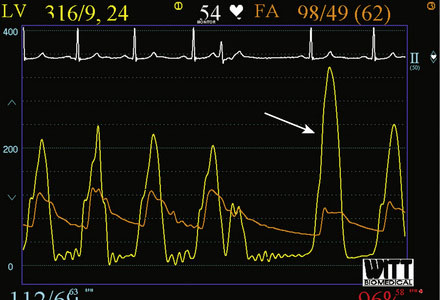

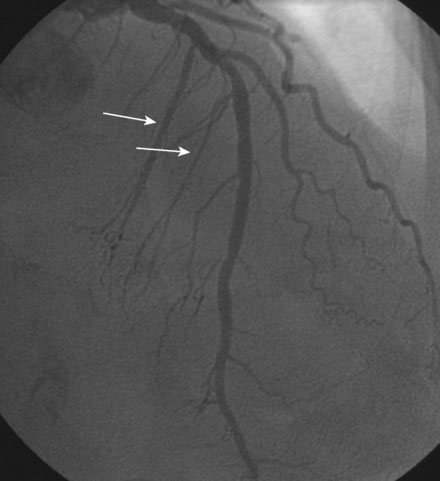

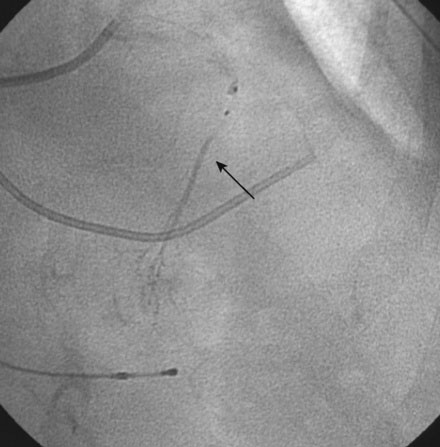

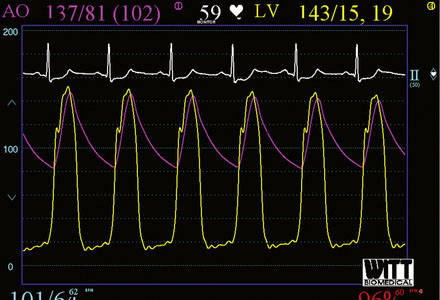

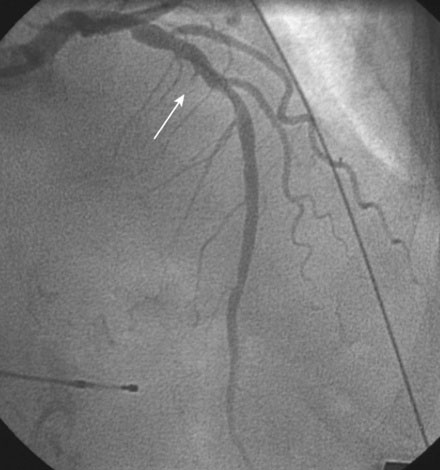

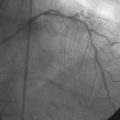

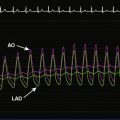

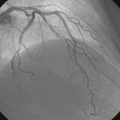

Right heart catheterization revealed a mean right atrial pressure of 4 mmHg, a pulmonary artery pressure of 34/14 with a mean of 21 mmHg, and a mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 13 mmHg. The aortic pressure waveform exhibited the characteristic “spike and dome” morphology seen in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (Figure 48-1). A multipurpose catheter with an end-hole and two side-holes at the tip was positioned in the left ventricular cavity. Simultaneous recording of left ventricular and femoral arterial pressure revealed a systolic gradient in excess of 100 mmHg at baseline; with provocation using a post-premature ventricular contraction the gradient exceeded 200 mmHg (Figures 48-2, 48-3). A slow pull-back of the catheter recorded no pressure gradient across the aortic valve (Figure 48-4). Left coronary angiography demonstrated several septal perforators appropriate for alcohol septal ablation (Figure 48-5 and Video 48-1).

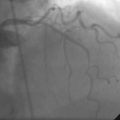

To perform the alcohol septal ablation procedure, the operator first positioned a temporary pacemaker into the right ventricular apex and tested the threshold to ensure capture. An angioplasty guide catheter was engaged into the left coronary ostium and 50 U/kg of unfractionated heparin were administered. A floppy-tipped, 0.014 inch guidewire was advanced into the larger of the first septal branches and a 2.0 mm diameter by 8 mm long over-the-wire balloon catheter was advanced over the wire into the proximal segment of the first septal perforator. The operator inflated the balloon and injected iodinated contrast into the left coronary artery to prove that the balloon was occlusive, thus isolating the septal perforator from the left coronary circulation (Figure 48-6 and Video 48-2). The operator then removed the 0.014 inch wire from the balloon catheter and, with the balloon still inflated, injected iodinated contrast through the lumen of the balloon to show that there was no leakage of contrast from the septal artery to the left anterior descending artery (Figure 48-7 and Video 48-3). With the balloon inflated in this septal perforator, the pressure gradient was observed to decrease by 30 mmHg. Meanwhile, apical long axis views of the left ventricle were obtained by transthoracic echocardiogram and 0.1 cc of an echo contrast agent (Definity) was injected into the lumen of the inflated balloon catheter. This resulted in a contrast effect within the septum localized to the upper septum at the site of contact of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve. Confident that the instrumented septal perforator represented an appropriate target for alcohol ablation, and rechecking that the balloon remained inflated, the operator slowly injected 3.5 cc of denaturated ethanol through the lumen of the inflated balloon catheter over 5 minutes, allowing it to dwell for 5 additional minutes before deflating the balloon. Alcohol injection completely obliterated the left ventricular outflow tract pressure gradient, and restored a normal appearance to the aortic pressure waveform (Figure 48-8). Conduction remained normal during the procedure and the patient reported moderate chest pain. After alcohol injection, angiography confirmed occlusion of the first septal perforator (Figure 48-9 and Video 48-4).

Discussion

Many patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy are either asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic. Symptoms may be caused by several mechanisms including obstruction (syncope or presyncope, dyspnea, chest pain), diastolic dysfunction (dyspnea), low cardiac output (fatigue), or palpitations (arrhythmia). Sudden cardiac death is a feature of some forms of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, but is unusual in older patients. The major risk factors for sudden cardiac death in this condition include history of ventricular fibrillation or sustained ventricular tachycardia, family history of premature sudden death, unexplained syncope, marked left ventricular hypertrophy (>30 mm), abnormal exercise blood pressure, and the presence of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia on Holter monitor.1

Most patients are effectively treated medically with beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers. Rarely, more aggressive management is warranted. This includes surgical myectomy and alcohol septal ablation. The indications for these procedures are similar and are summarized in Table 48-1. There remains heated controversy regarding the choice of these two procedures in the management of this condition.2,3 Advantages of surgical myectomy include the fact that it is capable of treating nearly all forms of obstruction with a high degree of success and with low complication rates at experienced centers. Surgical myectomy has been available for more than 40 years and there is excellent long-term outcome data available.4 Its disadvantages include the fact that it is major surgery and there are few centers and surgeons with significant experience in this procedure. Alcohol septal ablation is an attractive and much less invasive option. It is also highly successful in selected individuals but is highly dependent upon appropriate septal anatomy for optimal results. Although there are no randomized controlled data, alcohol septal ablation generally compares favorably to surgical myectomy with a similar extent of symptomatic improvement and reduction in outflow tract obstruction. The potential long-term effects of the myocardial scar created by the procedure continue to concern many experts in this field and about 8% to 10% of patients require a permanent pacemaker as a consequence of the procedure. The beneficial effects on the left ventricular outflow tract gradient, septal thickness, and symptom status remain stable over time.5 Recent, nonrandomized data suggest that surgical myectomy in patients less than 65 years of age resulted in better survival (free from death and severe symptoms) compared to alcohol septal ablation.6 Thus, alcohol septal ablation is usually reserved for patients with severe symptoms due to obstruction who are on medical therapy, who have appropriate septal anatomy, and who either are not candidates for surgical myectomy or are in an older age group.

TABLE 48-1 Indications for Surgical Myectomy or Alcohol Septal Ablation in Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

| Presence of NYHA Class 3, 4 symptoms on medical therapy or intolerant of medical therapy |

| Left ventricular outflow tract gradient > 50 mmHg at rest or following physiologic provocation |

| Significant septal hypertrophy (thickness > 1.8 mm) |

| Presence of systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve |

The success of alcohol septal ablation can be enhanced with the incorporation of myocardial contrast echocardiography.7 This technique ensures that the selected septal perforator supplies the portion of the septum responsible for the obstruction. On occasion, there may be more than one candidate septal perforator; contrast echo guidance can help localize the best choice for alcohol injection. In most cases, the gradient resolves immediately upon injection of alcohol. As shown in this case, a small gradient may return in the days after the procedure but over time, as the scar heals and with relief of obstruction, the gradient continues to decrease.8

The main risk of the procedure is complete heart block, which complicates 8% to 10% of procedures. For this reason, a well-functioning temporary pacemaker is required for all procedures prior to alcohol injection and should remain in place for at least 24 hours with continued, in-hospital rhythm monitoring for at least 3 to 4 days. A right bundle branch block, also observed in this case, complicates 68% of alcohol septal ablation procedures.9 Thus, in the presence of an underlying left bundle branch block, development of complete heart block can be expected. Rare but potentially serious complications include injury to the left anterior descending artery during instrumentation of the septal perforator and leakage of alcohol into the left anterior descending artery causing an anterior infarction.

1 Maron B.J., McKenna W.J., Danielson G.K., Kappenberger L.J., Kuhn H.J., Seidman C.E., Shah P.M., Spencer W.H., Spirito P., TenCate F.J., Wigle E.D. ACC/ESC clinical expert consensus document on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on clinical expert consensus documents and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1687-1713.

2 Maron B.J., Dearani J.A., Ommen S.R., Maron M.S., Schaff H.V., Gersh B.J., Nishimura R.A. The case for surgery in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2044-2053.

3 Hess O.M., Sigwart U. New treatment strategies for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Alcohol ablation of the septum: the new gold standard? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2054-2055.

4 Ommen S.R., Maron B.J., Olivotto I., Maron M.S., Cecchi F., Betocchi S., Gersh B.J., Acherman M.J., McCully R.B., Dearani J.A., Schaff H.V., Danielson G.K., Tajik A.J., Nishimura R.A. Long-term effects of surgical septal myectomy on survival in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:470-476.

5 Fernandes V.L., Nielsen C., Nagueh S.F., Herrin A.E., Slifka C., Franklin J., Spencer W.H. Follow-up of alcohol septal ablation for symptomatic hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. The Baylor and Medical University of South Carolina experience 1996–2007. J Am Coll Cardiol Interv. 2008;1:561-570.

6 Sorajja P., Valeti U., Nishimura R.A., Ommen S.R., Rihal C.S., Gersh B.J., Hodge D.O., Schaff H., Holmes D.R. Outcome of alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2008;118:131-139.

7 Holmes D.R., Valeti U.S., Nishimura R.A. Alcohol septal ablation for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Indications and technique. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;66:375-389.

8 Yoerger D.M., Picard M.H., Palacios I.F., Vlahakes G.J., Lowry P.A., Fifer M.A. Time course of pressure gradient response after first alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1511-1514.

9 Runquist L.H., Nielsen C.D., Killip D., Gazes P., Spencer W.H. Electrocardiographic findings after alcohol septal ablation therapy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:1020-1022.