CASE 48

RG is 45 years old and has recently returned from a trip to China. While there he visited several small local markets, as well as a number of other typical tourist sites, including the Great Wall near Beijing. Two weeks after his return he developed a fever, which seemed only to defervesce intermittently with acetaminophen. During the past 2 days he has complained to his family of feeling more short of breath than usual and has had a crushing headache. Finally, tonight his overall condition worsens and he comes to the emergency department.

QUESTIONS FOR GROUP DISCUSSION

RECOMMENDED APPROACH

Implication/Analysis of Clinical History

RG is short of breath and has had intermittent fever for the past 2 days and a crushing headache. All of these symptoms are typical of viral infections. Despite his travel history, which must be kept in mind, we should consider first those infections that are common. Thus, you need to ensure this is not a typical infection (e.g., community-acquired pneumonia) and/or viral infection. However, he should be quarantined during workup. RG has a fever, which is only resolved intermittently; therefore, to get his temperature under control use simple measures (e.g., acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) as well as sponging his body with warm water.

ETIOLOGY: WEST NILE VIRUS

West Nile virus is a mosquito-borne virus that belongs to the family of flaviviruses, as do the yellow fever and dengue viruses. Individuals infected with West Nile virus may have no symptoms, whereas others may have fever and headache, become comatose, and have long-lasting neurologic damage, including muscle paralysis. Generally, most people make a complete recovery. A few will have longer-term neurologic dysfunction, probably reflecting cross-reactivity between immune response to virus and common neuronal antigens (see Cases 28 and 30).

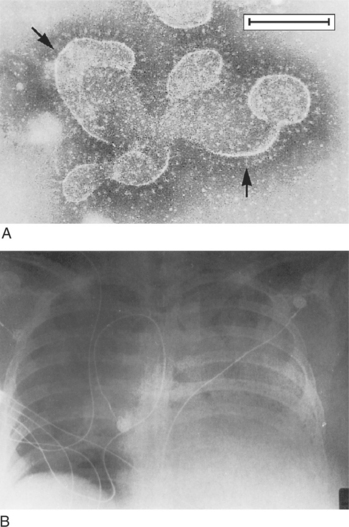

SARS is a coronavirus that has caused significant morbidity/mortality worldwide (Fig. 48-1). A large effort is being made to develop a protective vaccine effective before and after exposure. In addition, better diagnostic and prognostic indicators are needed. Recent data suggest evidence for overexpression of the novel prothrombinase fibroleukin in the lungs of sick patients (a phenomenon seen also in the case of other single stranded RNA viruses (e.g., fulminant hepatitis C infection). Procoagulants and prothrombinases play an important role in triggering fibrin deposition and thrombosis in small vessels. Thus, measures to prevent fibroleukin overexpression are another important therapeutic avenue of approach.

Ammann AJ. Leiner’s disease and C5 deficiency. J Pediatr. 1972;81:1221.

Bernard GR, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:699.

Bouffard JP, et al. Neuropathy of the brain and spinal cord in human West Nile virus infection. Clin Neuropathol. 2004;23:59.

Cook DN, Pisetsky DS, Schwartz DA. Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of human disease. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:975.

Das UN. Is insulin an anti-inflammatory molecule? Nutrition. 2001;17:409.

Eskola J, et al. Efficacy of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against acute otitis media. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:403.

Gando S, et al. Activation of the extrinsic coagulation pathway in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:2005.

Gioannini TL, et al. Isolation of an endotoxin-MD-2 complex that produced Toll-like receptor 4-dependent cell activation at picomolar concentrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4186.

Gould LH, FIkrig E. West Nile virus: A growing concern. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1102.

Hogrefe WR, et al. Performance of immunoglobulin G (IgG) enzyme linked immunosorbent assays using a West Nile virus recombinant antigen (preM/E) for detection of West Nile virus- and other flavivirus specific antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4641.

Kapoor AH, et al. Long persistence of West Nile virus (WNV) IgM antibodies in cerebral spinal fluid from patients with CNS disease. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:289.

Klee AL, et al. Long-term prognosis for clinical West Nile Virus infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1405.

Klugman KP, et al. A trial of a 9-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children with, and those without, HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1341.

Miyake K. Endotoxin recognition molecules: Toll like receptor-4-MD-2. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:11.

Nagi Y, et al. Essential role of MD-2 in LPS responsiveness and TLR4 distribution. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:667.

Ohnishi T, Muroi M, Tanamoto K. MD-2 is necessary for the Toll-like receptor 4 protein to undergo glycosylation essential for its translocation to the cell surface. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10:405.

Thomas L. Germs. N Engl J Med. 1972;287:553.

Watson JT, Gerber SI. West Nile virus: A brief review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:357.

Whitney CG, et al. Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1737.

Whitney CG, Pickering LK. The potential of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines for children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:961.

Wise RP, et al. Postlicensure safety surveillance of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. JAMA. 2004;292:1702.