CHAPTER 46

Lumbar Facet Arthropathy

Definition

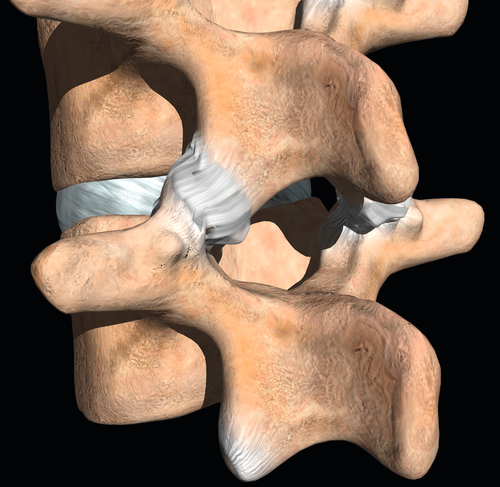

Lumbar facet joints are formed by the articulation of the inferior and superior articular facets of adjacent vertebrae (Fig. 46.1). These joints, located posteriorly in the spinal axis, are lined with synovium and have highly innervated joint capsules. Lumbar facet arthropathy refers to any acquired, traumatic, or degenerative process that changes the normal function or anatomy of a lumbar facet joint. These changes often disrupt the normal biomechanics of the joint, resulting in hyaline cartilage damage and ultimately periarticular hypertrophy. When they are painful, these joints may limit activities of daily living, work, and recreational sports. Lumbar facet joints may be a primary source of pain, but they are often painful concomitantly with a degenerative or injured lumbar disc, fracture, or ligamentous injury.

Lumbar facet arthropathy is more severe at the L4-L5 level and is common with advancing age and progressive intervertebral disc disease. These findings are independent of race and sex [1,2]. Postsurgical facet joint pain appears to be associated with advancing age, prolonged intraoperative time, intraoperative complications, discectomy, history of recurrent disc prolapse, and lack of rehabilitation [3,4].

Symptoms

Patients often complain of generalized or lateralized spinal pain, sometimes well localized. Pain may be provoked with spinal extension and rotation, from either a standing or a prone position. Relief with partial lumbar flexion is common. In the lumbar spine, these joints may refer pain into the buttock or posterior thigh but rarely below the knee [5–7]. Neurologic symptoms, such as lower extremity weakness, numbness, and paresthesias, would be unexpected from a primary facet joint disorder.

Physical Examination

A detailed examination of the lumbar spine and a lower extremity neurologic examination are considered standard procedure for those thought to have facet arthropathy. Although no portion of the examination has been shown to definitively correlate with the diagnosis of a facet joint disorder, the physical examination can be helpful in elevating the clinician’s level of suspicion for this diagnosis [8,9]. The examination starts with simple observation of the patient’s gait, posture, movement patterns, and range of motion. Generalized and segmental spinal palpation is followed by a detailed neurologic examination for sensation, reflexes, tone, and strength. In the absence of coexisting pathologic processes, such as lumbar radiculopathy, strength, sensation, and deep tendon reflexes should be normal.

Provocative maneuvers and nerve tension tests, including straight-leg raising, should accompany the evaluation to rule out any superimposed nerve root injury that might accompany a facet disorder. The clinician notes the patient’s response when the lower extremity is raised with the hip flexed and the knee extended. This “tension” placed on inflamed or injured lower lumbosacral nerve roots will provoke pain, paresthesias, or numbness down the extremity. Typically, in isolated cases of lumbar facet disorders, this maneuver does not provoke radiating symptoms into the lower extremity, but it may cause lower back pain. Some physicians find that facet pain can be reproduced with prone extension with rotation, hip extension, lumbar extension while standing on a single leg, and standing spinal extension.

Functional Limitations

Patients with lumbar facet joint arthropathy may experience difficulty with prolonged walking, stair climbing, twisting, standing, and prone lying. Because facet problems are common with underlying disc disease, patients often have difficulty with lumbar flexion activities, such as lifting, stooping, and bending.

Diagnostic Studies

Fluoroscopy-guided, contrast-enhanced, anesthetic intra-articular or medial branch blocks are considered the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of a painful lumbar facet joint (Figs. 46.2 and 46.3) [10–12]. Clinical history, examination findings, radiographic changes, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and bone scan have not been shown to correlate with facet joint pain [8,9,13].

Treatment

Initial

Initial treatment emphasizes local pain control with oral analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ice, topical creams, local blind periarticular corticosteroid injections, and avoidance of exacerbating activities. Spinal manipulations and acupuncture may also reduce local pain. Temporary wearing of corsets and limited activity may be used.

Rehabilitation

Physical therapy may include modalities to control pain (e.g., ice, heat, ultrasound), traction, instruction in body mechanics, flexibility training (including hamstring stretching), articular mobilization techniques, core strengthening, generalized conditioning, and restoration of normal movement patterns. Critical assessment of the biomechanics of specific activities that may be job related (e.g., sitting at a desk, carpentry work, driving) or sports related (e.g., running, cycling) is important. This assessment can result in prevention of recurrent episodes of pain because changes in a technique or activity may reduce the underlying forces at the joint level. Simple ergonomic measures that act to support the lumbar spine during sitting and standing may reduce the occurrence of low back pain from the facet joints. These measures include proper chair height and design, properly designed work table, and adjustable chair supports. While standing, the addition of a footrest, pads, and the ability to change body position routinely may reduce low back pain.

Procedures

Intra-articular, fluoroscopy-guided, contrast-enhanced facet injections are considered essential in the proper diagnosis and treatment of a painful facet joint [10,11,14–17]. Ultrasound guidance for these procedures is an emerging option [18–21]. Patients can be evaluated before and after injection to determine what portion of their pain can be attributed to the joints injected. After confirmation with contrast material, 1 to 2 mL of an anesthetic-corticosteroid mix is injected directly into the joint. An alternative approach is to perform anesthetic medial branch blocks with small volumes (0.1 to 0.3 mL) of anesthetic. Recent data suggest that medial branch blocks may be the preferred method for diagnosis of facet joint pain [16,22,23]. If the facet joint is found to be the putative source of pain, a medial branch neurotomy may be desirable [24–26].

Surgery

Surgery is rare in primary and isolated facet arthropathies. Surgical spinal fusion may be performed for discogenic pain, which may affect secondary cases of facet arthropathies.

Potential Disease Complications

Because a common cause of facet arthropathy is degenerative in nature, this disorder is often progressive, resulting in chronic, intractable spinal pain [26]. It often coexists with spinal disc abnormalities, further leading to chronic pain. This subsequently results in diminished spinal motion and weakness.

Potential Treatment Complications

Treatment-related complications may be caused by medications; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may cause gastrointestinal and renal problems, and analgesics may result in liver dysfunction and constipation. Local periarticular injections and acupuncture may cause local transient needle pain. Local manual treatments or injections will often cause transient exacerbation of symptoms. Intra-articular facet injections will cause transient local spinal pain and swelling and possibly bruising. More serious injection-related complications include an allergic reaction to the medications, injury to a blood vessel or nerve, trauma to the spinal cord, and infection. When more serious injection complications occur, they can usually be attributed to poor procedure technique [10].