CASE 46 Balloon Pericardial Window

Case presentation

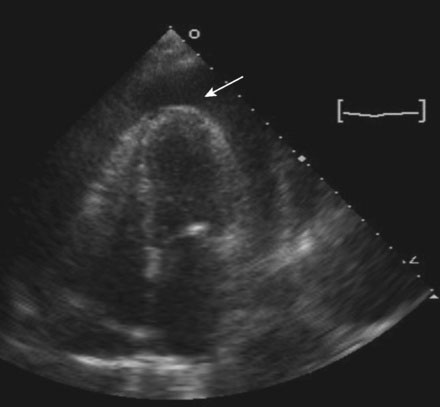

Upon presentation, she was in mild distress from dyspnea, but remained hemodynamically stable with a blood pressure of 150/70 mmHg and, although physical examination confirmed elevation of the jugular venous pressure, there was no pathologic pulsus paradoxus. The electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with low voltage and echocardiography revealed a large circumferential pericardial effusion (Figure 46-1) along with right ventricular collapse and right atrial inversion consistent with tamponade. She underwent pericardiocentesis with removal of 750 mL of serosanguineous fluid. Cytological analysis of the fluid subsequently confirmed adenocarcinoma. A pericardial drain remained in place and she was admitted for continued observation. Over the ensuing 2 days, more than 200 mL of fluid drained from the pericardial space each day. She was referred to the cardiac catheterization laboratory for a balloon pericardial window.

Cardiac catheterization

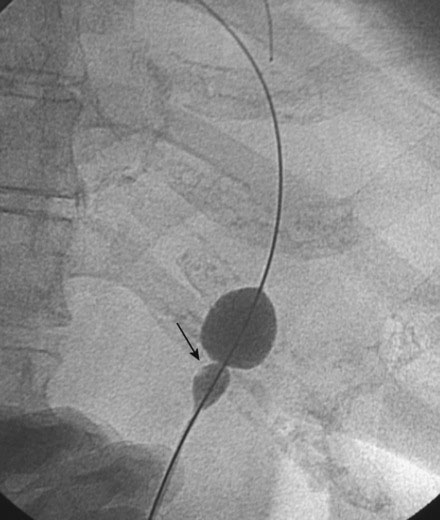

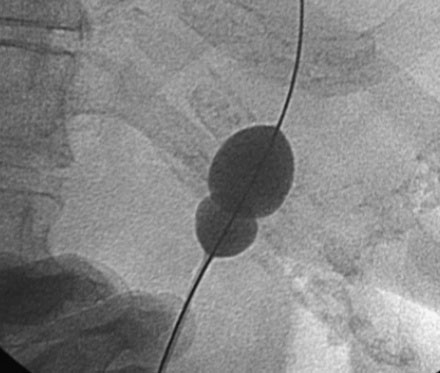

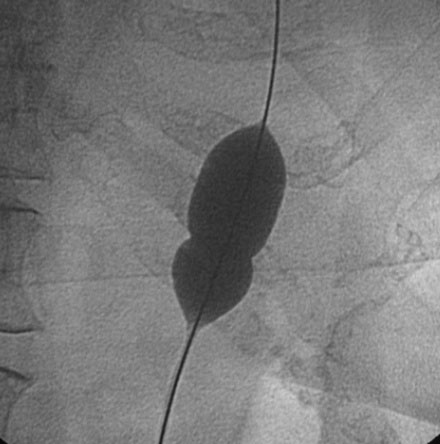

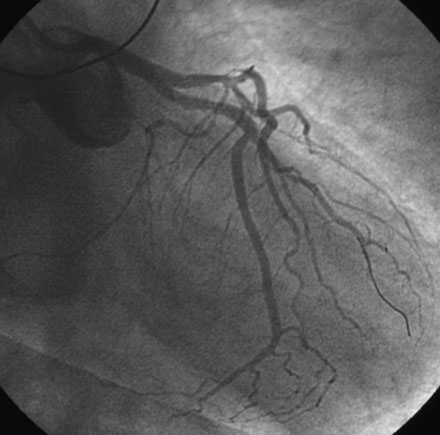

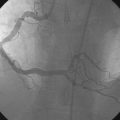

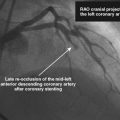

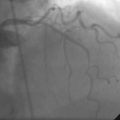

The patient was positioned on the cardiac catheterization table with the head and torso elevated at roughly 45 degrees. The pigtail catheter drain placed 2 days earlier was removed from the pericardial space. Using sterile technique, and following administration of local anesthesia, a long solid-core needle was positioned into the pericardial space from the subxiphoid approach. An additional 60 mL of fluid was removed from the pericardial space. A 0.038 inch “extra-stiff” Amplatz J-tipped guidewire was advanced through the needle into the pericardial space and the needle was removed. After administration of additional local anesthesia around the entry site, the operator created a tissue tract by passing a 10 French dilator over the guide wire. A valvuloplasty balloon (3 cm long and 20 mm in diameter) was prepared with dilute contrast and advanced along the wire so that the entire balloon was below the skin and the balloon centered across the inferior pericardial border. Prior to this step, the patient was placed in a fully recumbent position to prevent kinking of the catheter and allow easier passage. Using a 60 cc syringe, the balloon was gently inflated under fluoroscopic guidance (Figure 46-2) and a prominent “waist” was noted where the balloon crossed the pericardium. Additional inflation of the balloon led to complete balloon expansion (Figures 46-3, 46-4 and Video 46-1). The balloon was then removed over the guidewire and replaced with a pigtail catheter to remove any residual fluid. The pigtail catheter was then withdrawn and an occlusive dressing was applied to the wound.

Discussion

Recurrent effusion is an important limitation to pericardiocentesis and is particularly problematic for patients with malignant effusions, in whom life expectancy is limited. Percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy is an effective and less invasive alternative to a surgical pericardial window for palliation of recurrent malignant pericardial effusions.1 Performed with a valvuloplasty balloon at the time of pericardiocentesis and creating a rent or tear in the pericardium, the procedure allows drainage of pericardial fluid into the pleural and/or peritoneal space, thus preventing reaccumulation of pericardial fluid and its hemodynamic consequences. This procedure is most effective in patients with malignant effusions and should be avoided in patients with uremic pericarditis because of the increased risk of bleeding. In a multicenter registry involving 130 patients with mostly malignant pericardial effusion, balloon pericardial window was successful in 85% of patients, with success defined as no recurrence or need for surgery. The procedure was unsuccessful in 18 patients (15%); complications consisted of bleeding requiring surgery in five patients (all of whom had uremic pericardial effusions) and recurrence in 13 patients.2

1 Ziskind A.A., Pearce A.C., Lemmon C.C., Burstein S., Gimple L.W., Herrmann H.C., McKay R., Block P.C., Waldman H., Palacios I.F. Percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy for the treatment of cardiac tamponade and large pericardial effusions: description of technique and report of the first 50 cases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21:1-5.

2 Ziskind A.A., Lemmon C.C., Rodriguez S., Burstein S., Johnson S.A., Feldman T., Chow W.H., Gimple L.W., Palacios I.F. Final report of the percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy registry for the treatment of effusive pericardial disease. Circulation. 1994;90:I-647A.