CASE 45 Is Open-Heart Surgical Backup Necessary for PCI?

Cardiac catheterization

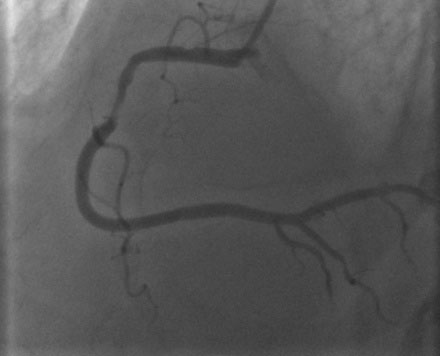

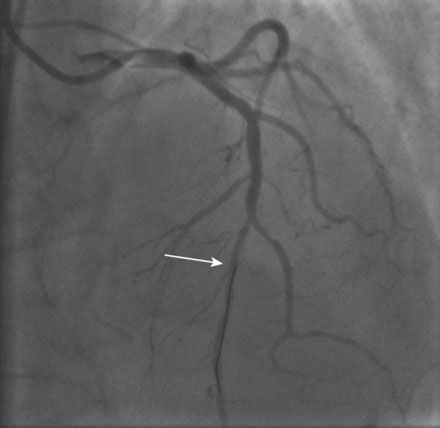

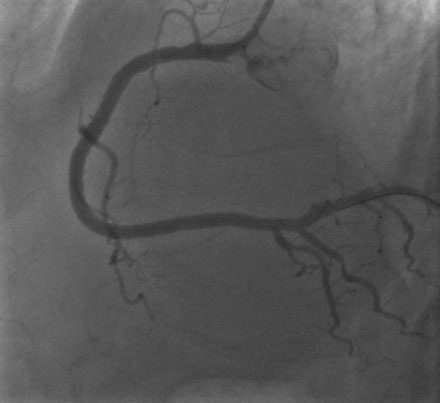

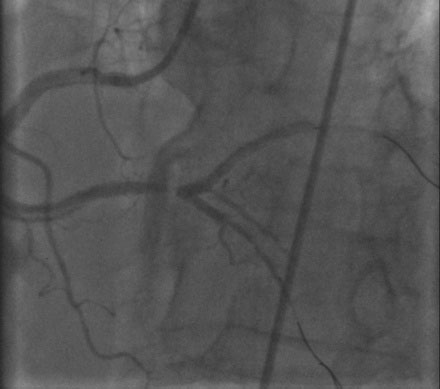

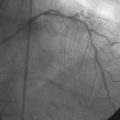

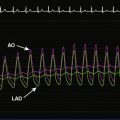

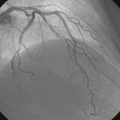

The patient stayed at the community hospital and the procedure was scheduled with an experienced interventional cardiologist (who performed more than 200 interventions each year), whose primary practice was at a large university hospital with surgical backup. Left ventricular function appeared normal with no wall motion abnormalities. The right coronary artery had a severe stenosis in the proximal segment; this lesion appeared hazy, but there was normal TIMI flow in the artery (Figure 45-1 and Video 45-1). The left coronary angiogram was notable for a normal appearing circumflex artery and a moderate lesion in the midsegment of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery (Figures 45-2, 45-3). To further assess the hemodynamic significance of the LAD stenosis, the operator measured fractional flow reserve (FFR); this calculated to 0.84 and was therefore deemed not significant.

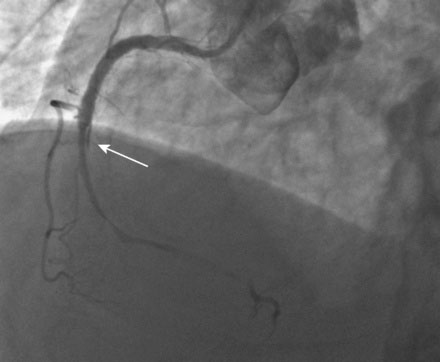

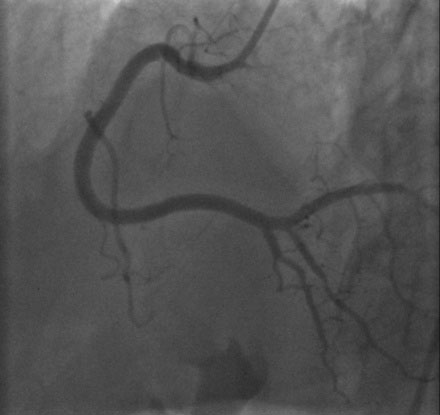

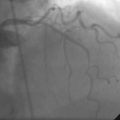

Thus, the interventionalist proceeded with PCI and placed a 6 French right Judkins guide catheter in the right coronary artery after procedural anticoagulation was achieved with bivalirudin. The operator first dilated the lesion with a 3.0 mm diameter by 20 mm long compliant balloon and then placed a 4.0 mm diameter by 28 mm long drug-eluting stent. As the operator was satisfied with the angiographic result in several views (Figures 45-4, 45-5 and Videos 45-2, 45-3), intravascular ultrasound was not performed and the case was terminated. The patient felt well with no chest pain or discomfort. Hemostasis was easily accomplished with a vascular closure device.

The patient had been moved off the cardiac catheterization laboratory table and onto a stretcher awaiting transfer to his hospital bed when he reported chest pain, diaphoresis, and nausea. The monitor leads showed marked ST-segment elevation and sinus bradycardia. Fearing acute stent thrombosis, the patient was immediately returned to the cardiac catheterization laboratory and the physician quickly regained arterial access and imaged the right coronary artery. The right coronary was completely occluded distal to the stent and there appeared to be a linear dissection beyond the distal end of the stent that was not apparent on the post-PCI films (Figure 45-6). At this point, the patient had ongoing severe chest pain and bradycardia but maintained an adequate arterial pressure.

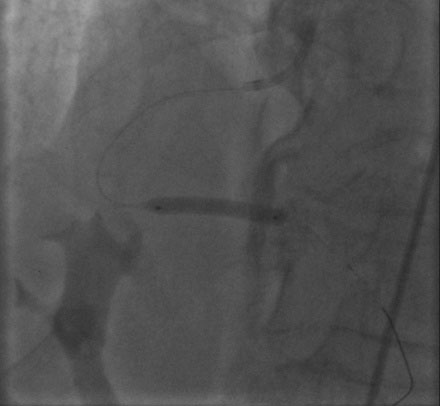

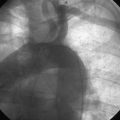

The operator administered atropine, unfractionated heparin, and eptifibatide, and attempted to open the artery. Gaining the true lumen proved extremely difficult, but finally the operator was able to insert floppy-tipped guidewires into both the posterior descending and the posterolateral branches (Figure 45-7). The angiogram revealed an extensive spiral dissection originating at the distal end of the stent and progressing to the bifurcation of the posterior descending and posterolateral branches. The operator placed bare-metal stents at the origin of both the posterolateral artery (Figure 45-8 and Video 45-5) and the posterior descending artery (Figure 45-9) and then placed bare-metal stents distal to proximal in an effort to cover the dissection flap (Figure 45-10). Once patency was restored, the patient no longer complained of chest discomfort, the bradycardia resolved, and the ST segments returned to normal. The final angiographic result after multiple stents were inserted is shown in Figure 45-11 and Video 45-6.

Discussion

The unpredictable nature of balloon angioplasty characterizing the early era of percutaneous coronary intervention mandated the need for surgical backup for all coronary interventional procedures. Without the coronary stents, technology, and pharmacology we enjoy today, flow-limiting dissections, threatened or abrupt closure, and coronary perforations could only be managed surgically. During this early era, emergency bypass surgery was needed in up to 5% of balloon angioplasties. In the stent era, this has been reduced to less than 0.5%.1–3

In the modern era, indications for emergency surgery include the presence of triple vessel disease (40% of cases), dissection or acute closure (43% of cases), perforation (8% of cases), and failure to cross the lesion (8% of cases).4 Unfortunately, as evidenced by the case presented here, there do not appear to be clear-cut risk factors that identify which patients are at increased risk for this complication.5 Clearly, patients requiring PCI of calcified, complex stenoses or chronic total occlusion should not undergo these procedures at institutions without surgical backup. However, the case shown here is an example of a patient with a very straightforward coronary lesion that was initially successfully treated percutaneously but would have required emergency bypass for an extensive dissection if the operator had not been fortunate or skilled enough to successfully treat the complication percutaneously.

Despite the low rate of emergency bypass surgery in the modern era, current professional guidelines continue to classify elective coronary interventional procedures without on-site surgical backup as a Class III indication.6 Emergency angioplasty performed to reperfuse an ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction is classified as a IIb indication, with multiple caveats as follows6:

These recommended guidelines remain controversial but have not been modified in the 2007 and 2009 PCI updates. Currently, many community hospitals throughout the nation perform elective PCI without on-site surgical backup and/or perform primary PCI for ST-segment elevation MI without adhering to these numerous stipulations. The number of such centers continues to grow.7 The most recent data from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) reported that 13% of participating hospitals perform PCI without on-site surgical backup, representing 2.8% of patients undergoing PCI in that registry.8 Although this data is not randomized and patients may have been carefully selected at the sites without surgical backup, the centers performing PCI without on-site surgical backup had similar rates of emergent CABG and risk-adjusted mortality when compared to centers with on-site surgical backup, despite lower annual PCI procedural volumes. Several other published reports suggest that elective PCI at centers without on-site surgical backup is safe and feasible.9–11 However, a large report consisting of Medicare enrollees found a higher mortality for patients undergoing non-primary or rescue PCI at centers without on-site surgical backup.12 Clearly, this issue will not be resolved until a large-scale, randomized trial is performed.

Although the risk is small, in the author’s experience, when emergency surgery is needed, it is needed desperately and it is needed immediately. Abrupt vessel closure of an artery supplying a large vascular territory will not be tolerated very long without serious morbidity or death. Similarly, a perforation that cannot be sealed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory is a true emergency requiring immediate attention. Stabilization for transfer to an institution miles away may not be possible in some cases. In addition, the delays involved in arranging for transfer and physically transporting a patient to another institution for emergency surgery will likely be associated with serious and potentially unnecessary morbidity. One study estimates that one in four patients referred for emergency bypass surgery after failed PCI would be placed at increased risk of harm if delays to surgery were present.13

1 Detre K.M., Holubkov R., Kelsey S., et al. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in 1985-1986 and 1977-1981: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Registry. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:265-270.

2 Seshadri N., Whitlow P.L., Acharya N., Houghtaling P., Blackstone E.H., Ellis S.G. Emergency coronary artery bypass surgery in the contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention era. Circulation. 2002;106:2346-2350.

3 Yang E.H., Gumina R.J., Lennon R.J., Holmes D.R., Rihal C.S., Singh M. Emergency coronary artery bypass surgery for percutaneous coronary interventions. Changes in the incidence, clinical characteristics, and indications from 1979-2003. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:2004-2009.

4 Roy P., de Labriolle A., Hanna N., Bonello L., Okabe T., Slottow T.L.P., Steinberg D.H., Torguson R., Kaneshige K., Xue Z., Satler L.F., Kent K.M., Suddath W.O., Pichard A.D., Lindsay J., Waksman R. Requirement for emergency coronary artery bypass surgery following percutaneous coronary intervention in the stent era. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:950-953.

5 Shubrooks S.J., Nesto R.W., Leeman D., Waxman S., Lewis S.M., Fitzpatrick P., Dib N. Urgent coronary bypass surgery for failed percutaneous coronary intervention in the stent era: is backup still necessary? Am Heart J. 2001;142:190-196.

6 Smith S.C.Jr, Feldman T.E., Hirshfeld J.W.Jr, Jacobs A.K., Kern M.J., King S.B.III, Morrison D.A., O’Neill W.W., Schaff H.V., Whitlow P.L., Williams D.O. ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/SCAI Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1-121.

7 Dehmer G.J., Kutcher M.A., Dey S.K., Shaw R.E., Weintraub W.S., Mitchell K., Brindis R.G., Frequency of percutaneous coronary interventions at facilities without on-site cardiac surgical backup – a report from the American College of Cardiology – National Cardiovascular Data Registry (ACC-NCDR). On behalf of the ACC-NCDR Am J Cardiol 2007;99:329-332.

8 Kutcher M.A., Klein L.W., Ou F.S., Wharton T.P., Dehmer G.J., Singh M., Anderson H.V., Rumsfeld J.S., Weintraub W.S., Shaw R.E., Sacrinty M.T., Woodward A., Peterson E.D., Brindis R.G., Percutaneous coronary interventions in facilities without cardiac surgery on site: a report from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR). On behalf of the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:16-24.

9 Ting H.H., Garratt K.N., Singh M., Kjelsberg M.A., Timimi F.K., Cragun K.T., Houlihan R.J., Boutchee K.L., Crocker C.H., Cusma J.T., Wood D.L., Holmes D.R. Low risk percutaneous coronary interventions without on-site cardiac surgery: Two years’ observational experience and follow-up. Am Heart J. 2003;145:278-284.

10 Paraschos A., Callwood D., Wightman M.B., Tcheng J.E., Phillips H.R., Stiles G.L., Daniel J.M., Sketch M.H. Outcomes following elective percutaneous coronary intervention without on-site surgical backup in a community hospital. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:1091-1093.

11 Frutkin A.K., Mehta S.K., Patel T., Menon P., Safley D.M., House J., Barth C.W., Grantham J.A., Marso S.P. Outcomes of 1090 consecutive, elective, nonselected percutaneous coronary interventions at a community hospital without onsite cardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:53-57.

12 Wennberg D.E., Lucas F.L., Siewers A.E., Kellett M.A., Malenka D.J. Outcomes of percutaneous coronary interventions performed at centers without and with onsite coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA. 2004;292:1961-1968.

13 Lofti M., Mackie K., Dzavik V., Seidelin P.H. Impact of delays to cardiac surgery after failed angioplasty and stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:3337-3342.