CHAPTER 43

Thoracic Radiculopathy

Darren Rosenberg, DO; Daniel C. Pimentel, MD

Definition

Thoracic radiculopathy is a painful syndrome caused by mechanical compression, chemical irritation, or metabolic abnormalities of the thoracic spinal nerve root. Thoracic disc herniation accounts for less than 5% of all disc protrusions [1,2]. It accounts for less than 2% of all spinal disc surgeries and 0.15% to 4% of all symptomatic spinal disc herniations [3]. The majority of thoracic disc herniations (35%) occur between the levels of T8 and T12, with a peak (20%) at T11-12. Most patients (90%) present clinically between the fourth and seventh decades of life; 33% present between the ages of 40 and 49 years. Approximately 33% of thoracic disc protrusions are lateral, preferentially encroaching on the spinal nerve root. The remainder are central or central lateral, resulting primarily in various degrees of spinal cord compression. Synovial cysts, although rare in the thoracic spine (0.06% of patients requiring decompressive surgery), may also be responsible for foraminal encroachment. These tend to be more common at the lower thoracic levels [4].

Natural degenerative forces and trauma are generally thought to be the most important factors in the etiology of mechanical thoracic radiculopathy. Foraminal stenosis from bone encroachment may also cause compression of the exiting nerve root and radicular symptoms. Perhaps one of the most common metabolic causes of thoracic radiculopathy is diabetes, often resulting in multilevel disease [4]. This may occur at any age but often appears with other neuropathic symptoms due to injury to the blood supply to the nerve root. Finally, another etiology that should be considered a possible cause of thoracic radiculopathy is neoplastic compression. Primary spine tumors are rare, although the spine is a frequent metastasis site (4%-15%) of primary solid tumors, such as breast, lung, and prostate cancer [5]. Regarding spine metastasis, the thoracic spine is the most commonly affected (70%), followed by lumbar (20%) and cervical (10%) [6].

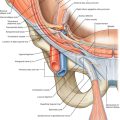

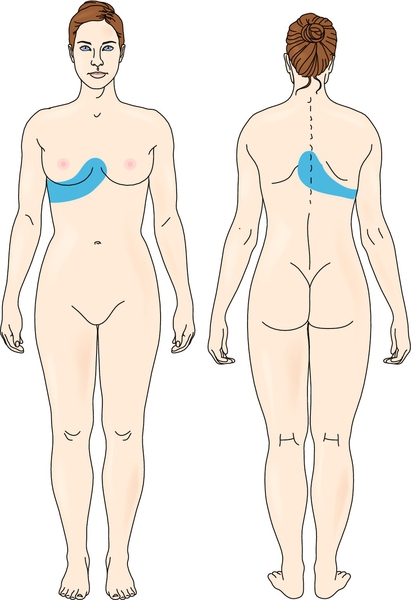

Symptoms

Most patients (67%) present with complaints of “band-like” chest pain (Fig. 43.1). The second most common symptom (16%) is lower extremity pain [7]. Injury to nerve roots T2-3 may be manifested as axillary or midscapular pain. Injury to nerve roots T7-12 may be manifested as abdominal pain [8]. Unlike thoracic radiculopathy, spinal cord compression produces upper motor neuron signs and symptoms consistent with myelopathy. Therefore examiners should pay close attention to the presence of motor impairment, hyperreflexia and spasticity, sensory impairment, and bowel and bladder dysfunction. The last may be caused by T11-12 lesions damaging the conus medullaris or cauda equina [9].

Thus, in thoracic radiculopathy, pain—localized, axial, or radicular—is the primary complaint in 76% of patients. It is also important to include in the history any trauma (present in 37% of patients) [10] or risk factors for non-neurologic causes of chest wall or abdominal pain. Thoracic compression fractures that may mimic the symptoms of thoracic radiculopathy may be seen in young people with acute trauma, particularly falls, regardless of whether they land on their feet. In older people (particularly women with a history of osteopenia or osteoporosis) or in individuals who have prolonged history of steroid use, a compression fracture should be considered. Because thoracic radiculopathy is not common, it is important in nontraumatic cases to be suspicious of more serious pathologic processes, such as malignant disease. Therefore a history of weight loss, decreased appetite, and previous malignant disease should be elicited.

Physical Examination

The physical examination may show only limitations of range of motion—particularly trunk rotation, flexion, and extension—generally due to pain. In traumatic cases, location of ecchymosis or abrasions should be noted. Range of motion testing should not be done repeatedly if an acute spinal fracture is suspected. Careful palpation for tenderness over the thoracic spinous and transverse processes as well as over the ribs and intercostal spaces is critical in localizing the involved level. Pain with percussion over the vertebral bodies should alert the clinician to the possibility of a vertebral fracture.

On the other hand, uncommon symptoms in the lower limbs, such as pain, reflex changes, spasticity, and weakness, can be a result of spinal cord compression by thoracic disc herniation [11], although this phenomenon is seldom observed.

Physical examination in diagnosis of thoracic radiculopathy has a modest accuracy and reliability because there is difficulty in testing strength of possibly affected muscles (such as paraspinal, intercostal, and abdominal muscles) isolatedly [12], although it is crucial for ruling out other possible causes of pain or neurologic abnormalities. In addition, sensation may be abnormal in a dermatomal pattern. This will direct the examiner to more closely evaluate the involved level. Any abnormalities of the spine should be noted, including scoliosis, which is best detected when the patient flexes forward. A thorough examination of the cardiopulmonary system, abdominal organs, and skin should be performed, particularly in individuals who have sustained trauma or relevant comorbidities.

Functional Limitations

The pain produced by thoracic radiculopathy often limits an individual’s movement and activity. Patients may be limited in activities such as dressing and bathing and other activities that include trunk movements, such as putting on shoes. Work activities may be restricted, such as lifting, climbing, and stooping. Even sedentary workers may be so uncomfortable that they are not able to perform their jobs. Anorexia may result from pain in the abdominal region.

Diagnostic Studies

Because of the low incidence of thoracic radiculopathy and the possibility of serious disease (e.g., tumor), the clinician should have a low threshold for ordering imaging studies in patients with persistent (more than 2 to 4 weeks) thoracic pain of unknown origin. Magnetic resonance imaging remains the imaging study of choice to evaluate the soft tissue structures of the thoracic spine. Computed tomography and computed tomographic myelography are alternatives if magnetic resonance imaging cannot be obtained.

The electromyographic evaluation of thoracic radiculopathy can be challenging because of the limited techniques available and the lack of easily accessible muscles representing a myotomal nerve root distribution. The muscles most commonly tested are the paraspinals, intercostals, and abdominals. The clinician must investigate multiple levels of the thoracic spine to best localize the lesion. Techniques for intercostal somatosensory evoked potentials have also been shown to isolate individual nerve root levels [8].

In patients who have sustained trauma, plain radiographs are advised to rule out fractures and spinal instability.

Treatment

Initial

Pain control is important early in the disease course. Patients should be advised to avoid activities that cause increased pain and to avoid heavy lifting. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are often the first line of treatment and help control pain and inflammation. Oral steroids can be powerful anti-inflammatory medications and are typically used in the acute stages. This is generally done by starting at a moderate to high dose and tapering during several days. For example, a methylprednisolone (Medrol) dose pack is a prepackaged prescription that contains 21 pills. Each pill is 4 mg of Solu-Medrol. The pills are taken during the course of 6 days. On the first day, six tablets are taken, and then the dose is decreased by one pill each day. Both non-narcotic and narcotic analgesics may be used to control pain. In subacute or chronic cases, other medications may be tried, such as tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsants (e.g., gabapentin and carbamazepine), which have been effective in treating symptoms of neuropathic origin [13,14]. Moist heat or ice can be used, as tolerated, for pain. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation units may also help with pain [15].

Rehabilitation

Physical therapy can be used initially to assist with pain control. Modalities such as ultrasound and electrical stimulation may reduce pain and improve mobility [16]. Physical therapy can then progress with spine stabilization exercises, back and abdominal strengthening [17], and a trial of mechanical spine traction [18]. Some patients may benefit from a thoracolumbar brace to reduce segmental spine movement [19], although it should be carefully used because of possible postural muscle weakness that can result from its long-term use. Patients with significant spinal instability documented by imaging studies should be referred to a spine surgeon.

In addition, physical therapy should address postural retraining, particularly for individuals with habitually poor posture. Work sites can be evaluated, if indicated. All sedentary workers should be counseled on proper seating, including use of a well-fitting adjustable chair with a lumbar support. More active workers should be advised on appropriate lifting techniques and avoidance of unnecessary trunk rotation.

Finally, physical therapy can focus on improving biomechanical factors that may play a role in abnormal loads on the thoracic spine. These include flexibility exercises for tight hamstring muscles and orthotics for pes planus (flat feet).

Procedures

Transforaminal injections can have both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes [20]. They have been shown to significantly reduce radiating pain [21]. This is done under fluoroscopic guidance to minimize risk of injury to the lung and to ensure the accuracy of the level of injection.

Surgery

Thoracoscopic microsurgical excision of herniated thoracic discs has been shown to have excellent outcomes with less surgical time, less blood loss, fewer postoperative complications, and shorter hospitalizations than more traditional and invasive surgical approaches [22,23]. Traditionally, mechanical causes of thoracic radiculopathy have been treated with posterior laminectomy, lateral costotransversectomy, or anterior discectomy by a transthoracic approach. In a cohort study with 167 patients who underwent thoracoscopic discectomy, 79% reported a good or excellent outcome regarding pain improvement, and 80% reported good or excellent outcome for motor function [24].

Potential Disease Complications

If it is left untreated, thoracic radiculopathy can result in chronic pain and its associated comorbidities. Progressive thoracic spinal cord compression, if unrecognized, can lead to paraparesis, neurogenic bowel and bladder, and spasticity.

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Care should be taken with use of steroids in diabetic patients because they may elevate blood glucose levels. In patients with uncontrolled diabetes who present with thoracic radiculopathy, glucose control should be attempted, although extremely elevated serum glucose levels have not been proved to cause the diabetic form of thoracic radiculopathy. Because of the risk of gastric ulceration, steroids are not typically used simultaneously with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Rarely, short-term oral steroid use may produce avascular necrosis of the hip. Tricyclic antidepressants may cause dry mouth and urinary retention. Along with anticonvulsants, they may also cause sedation. On occasion, physical therapy may exacerbate symptoms. The risks of invasive pain procedures and surgery, including bleeding, infection, and further neurologic compromise, are well documented.