CASE 42 Coronary Cavernous Fistula

Case presentation

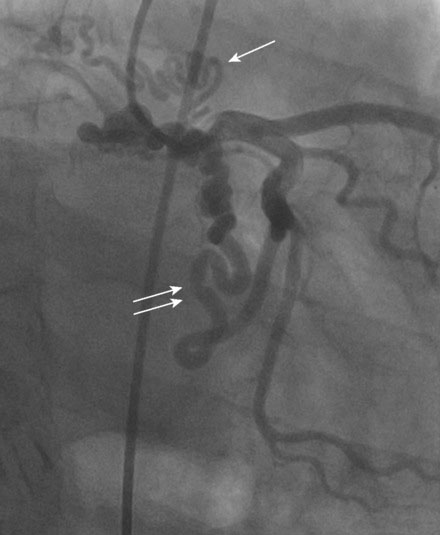

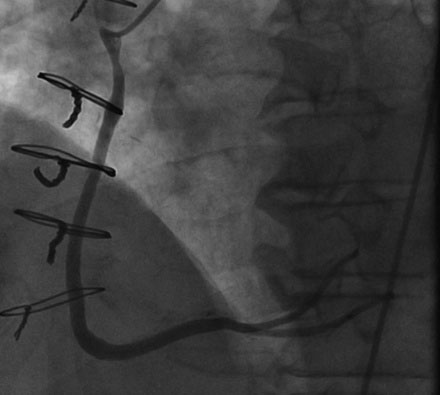

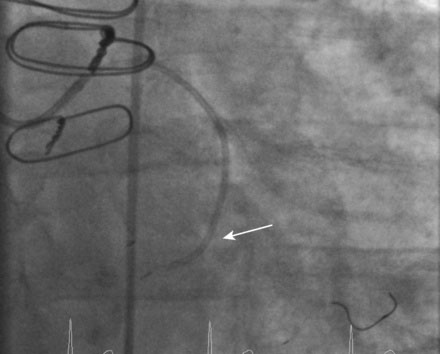

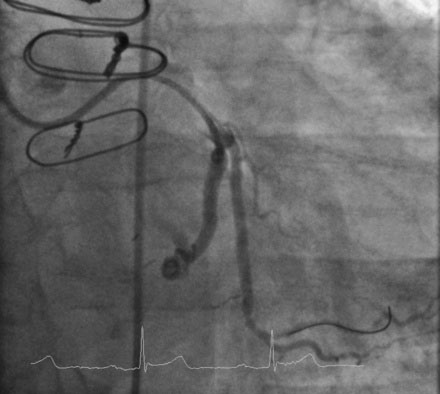

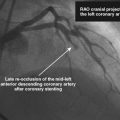

A 55-year-old man presented for management of a coronary cavernous fistula. One year prior to presentation, this otherwise healthy and active man with a history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obstructive sleep apnea developed progressive shortness of breath with exertion. This ultimately progressed to rest dyspnea and he presented to a local hospital with congestive heart failure requiring hospitalization. An echocardiogram found normal systolic function and no valvular abnormalities. Suspicious of coronary artery disease, his physician referred him for cardiac catheterization. To the operator’s surprise, the angiogram revealed a massive right coronary artery to right atrial fistula (Figure 42-1 and Video 42-1) and several fistulous connections from the left circumflex to the right atrium (Figure 42-2 and Video 42-2). The left anterior descending artery appeared normal, with no fistulae identified, and ventricular function was normal.

Cardiac catheterization

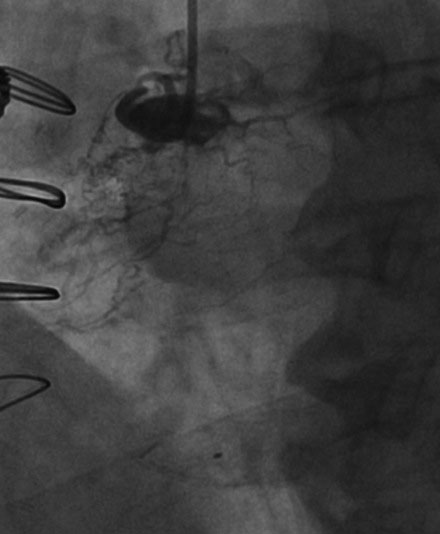

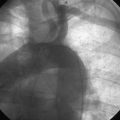

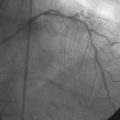

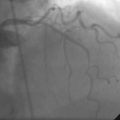

Right heart catheterization found fairly normal right sided pressures (mean right atrial pressure of 8 mmHg and pulmonary artery pressure of 27/5 mmHg). The oxygen saturation of blood sampled from the pulmonary artery was 67% with no evidence of a significant left-to-right shunt by oximetry. Cardiac output by the Fick method was 5.07 L/min. Angiography revealed wide patency of the vein graft to the right coronary (Figure 42-3) and continued exclusion of the fistula with no evidence of the fistula from the right coronary (Figure 42-4 and Video 42-3). The left coronary artery demonstrated a single fistulous connection to the right atrium (Figure 42-5 and Video 42-4) representing the distal fistula; the more proximal fistula previously noted was no longer evident.

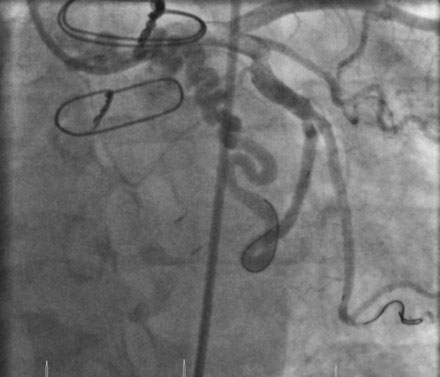

A 6 French 4.5 C-shaped guide catheter was inserted in the left coronary artery, and 50 U/kg of unfractionated heparin was administered. A 300 cm 0.014 inch floppy-tipped guidewire was advanced into the distal circumflex and a second, 300 cm 0.014 inch floppy-tipped guidewire placed into the fistula (Figure 42-6 and Video 42-5). A 4 French JB1 catheter was then advanced over this latter wire and positioned into the fistula and the 0.014 inch guidewire was removed (Figure 42-7). Contrast injected through the JB1 catheter confirmed an acceptable position in the fistula (Video 42-6). A Cook stainless-steel embolization coil (38-4-3) was then advanced through the catheter using a 0.038 inch Cook Newton wire, and positioned into the fistula (Video 42-7). This did not completely occlude the fistula. Thus, a second coil was placed, successfully occluding flow (Figure 42-8 and Video 42-8). The guidewire and catheter were removed from the circumflex artery and a final angiogram was obtained, showing no residual flow in the fistula (Video 42-9).

Discussion

Many fistulae are asymptomatic. If symptoms are present, they include angina, dyspnea, and heart failure and are usually caused by a large left-to-right shunt, high cardiac output, or coronary steal and associated ischemia.1,2 In addition, a fistula may become aneurysmal and rupture, causing hemopericardium, or may become a nidus for infective endocarditis.

A variety of percutaneous methods to close coronary fistulae have been described, including coils, vascular occlusion plugs, covered stents, and umbrella devices.3–5 These procedures may be very challenging technically depending on the anatomy, and are effective at closing the fistula in 80% to 85% of cases.3 Complications include device embolization, coronary artery dissection, myocardial infarction, and arrhythmia. Surgery may be preferred in the presence of extreme tortuosity, multiple drainage sites, or the presence of significant coronary artery branches at the site of device delivery.

1. Liberthson R.R., Sagar K., Berkoben J.P., Weintraub R.M., Levine F.H. Congenital coronary arteriovenous fistula. Report of 13 patients, review of the literature and delineation of management. Circulation. 1979;59:849-854.

2. Brueck M., Bandorski D., Vogt P.R., Kramer W., Heidt M.C. Myocardial ischemia due to an isolated coronary fistula. Clin Res Cardiol. 2006;95:550-553.

3. Armsby L.R., Keane J.F., Sherwood M.C., Forbess J.M., Perry S.B., Lock J.E. Management of coronary artery fistulae. Patient selection and results of transcatheter closure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1026-1032.

4. Collins N., Mehta R., Benson L., Horlick E. Percutaneous coronary artery fistula closure in adults: Technical and procedural aspects. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;69:872-880.

5. Olivotti L., Moshiri S., Santoro G., Nicolino A., Chiarella F. Percutaneous closure of a giant coronary arteriovenous fistula using free embolization coils in an adult patient. J Cardiovasc Med. 2008;9:733-736.