CHAPTER 41

Wrist Rheumatoid Arthritis

Melissa A. Klausmeyer, MD; Chaitanya S. Mudgal, MD, MS (Orth), MCh (Orth)

Definition

Rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic autoimmune disorder involving the synovial joint lining and is characterized by chronic symmetric erosive synovitis. It has been estimated that 1% to 2% of the world’s population is affected by this disorder. Women are affected more frequently with a ratio of 2.5:1. The cause of rheumatoid arthritis is thought to be multifactorial, including both genetic and environmental factors. The diagnostic criteria for rheumatoid arthritis include symptoms (morning stiffness, symmetric joint swelling, and skin nodules), laboratory test results, and radiographic findings. The wrist is among the most commonly involved peripheral joints; more than 65% of patients have some wrist symptoms within 2 years of diagnosis, increasing to more than 90% by 10 years. Of patients with wrist involvement, 95% have bilateral involvement [1–5].

The inflamed and hypertrophied synovial tissue is responsible for the destruction of adjacent tissues and resultant deformities. The cascade of events that lead to articular cartilage damage is a T cell–mediated autoimmune process mediated by the HLA class II locus [4,5]. The synovium is infiltrated by destructive molecules, resulting in thickening and proliferation of the synovium, chemotactic attraction of polymorphonuclear cells, and release by the polymorphonuclear cells of lysosomal enzymes and free oxygen radicals, which destroy joint cartilage.

The wrist articulation can be divided into three compartments, all of which are lined by synovium and therefore involved in rheumatoid arthritis: the radiocarpal, midcarpal, and distal radioulnar joints. Cartilage loss from both degradation and synovial proliferation contributes to ligamentous laxity of the extrinsic and intrinsic wrist ligaments. The laxity around the wrist leads to the classic rheumatoid deformities of carpal supination and ulnar translocation. The normally stout volar radioscaphocapitate ligament and the dorsal radiotriquetral ligament, which are important stabilizers of the carpus in relation to the distal radius, are stretched, resulting in ulnar translocation of the carpus. Laxity of the volar radioscaphocapitate ligament leads to loss of the ligamentous support to the waist of the scaphoid as well as weakening of the intrinsic scapholunate ligament. The scaphoid responds by adopting a flexed posture, and this is accompanied by radial deviation of the hand at the radiocarpal articulation. The bony carpus supinates and subluxes palmarly and ulnarly; thus, the ulna is left relatively prominent on the dorsal aspect of the wrist, a condition sometimes referred to as the caput ulnae syndrome [5–7]. The secondary effect of carpal supination is subluxation of the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon in a volar direction to the point that it no longer functions effectively as a wrist extensor. The bony architecture of the wrist is affected secondarily, in that the inflammatory cascade also stimulates bone-resorbing osteoclasts, which cause subchondral and periarticular osteopenia.

Areas of the wrist that display vascular penetration into bone or contain significant synovial folds, such as the radial attachment of the radioscaphocapitate ligament (the most radial of the volar radiocarpal ligaments), the waist of the scaphoid, and the base of the ulnar styloid (prestyloid recess), are the most common sites of progressive synovitis. The results of chronic erosive changes in these areas are bone spicules that can abrade and weaken tendons passing in their immediate vicinity, ultimately causing tendon rupture and functional deterioration. The extensor tendons to the small finger and ring finger (Vaughn-Jackson syndrome) [8], which rupture at the level of the ulnar head (see caput ulnae syndrome earlier), and the flexor tendon of the thumb at the level of the scaphoid (Mannerfelt syndrome) [9] are the most commonly involved. In addition to mechanical abrading, the extensor tendons are enclosed in a sheath of synovium at the wrist, which makes them susceptible to the damaging changes of synovial hypertrophy that is commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis. The synovial proliferation causes changes in tendons of both an ischemic and inflammatory nature, which make them susceptible to weakening and eventual rupture.

Symptoms

Three distinct areas of the wrist can be the source of symptoms from rheumatoid disease: the distal radioulnar joint, the radiocarpal joint, and the extensor tendons. However, symptoms can originate as far proximal as the cervical spine or involve the shoulder and the elbow. Joint-related symptoms in early disease include swelling and pain, with morning stiffness as a classic characteristic. Loss of motion in the early stages usually results from synovial hypertrophy and pain. Progressive loss of motion is seen with disease progression and represents articular destruction. The distal radioulnar joint can be painful because of inflammation within the joint, and it can be a source of decreased forearm rotation (Figs. 41.1 and 41.2). Later stages of the disease usually are manifested with complaints of severe pain, decreased motion, significant cosmetic concerns, and difficulties in performing activities of daily living. Erosive changes are more strongly associated with changes in subjective disability than joint space narrowing is [10].

Tenosynovitis of the tendons traversing the dorsal wrist can often be manifested as a painless swelling. Patients with advanced rheumatoid disease in the wrist or those unresponsive to medical management may present with loss of extension of the digits at the metacarpophalangeal joints or with inability to flex the thumb at the interphalangeal articulation. These findings result from extensor digitorum communis tendon ruptures over the dorsal aspect of the wrist or a rupture of the flexor pollicis longus over the volar scaphoid as described before. Deformity of the wrist and hand is often the most concerning factor for patients and is attributable to the progressive carpal rotation and translocation discussed earlier, coupled with the extensor tendon imbalance accentuated at the metacarpophalangeal joints of the hand, which causes ulnar drift of the digits. The compensatory ulnar deviation occurs at the metacarpophalangeal joints, and it can often be the presenting symptom in undiagnosed or untreated patients.

Symptoms of median nerve compression and dysfunction (altered or absent sensation primarily in the radially sided digits and night pain and paresthesias in the hand) can be associated with rheumatoid arthritis as well. This is primarily due to hypertrophy of the tenosynovium around the flexor tendons within the confined space of the carpal canal, with resulting compression of the median nerve. Vascular damage of the peripheral nerve (rheumatoid neuropathy) may also contribute to symptoms [11].

Physical Examination

Keeping in mind the three primary locations of rheumatoid involvement in the wrist, careful physical examination can help identify the sources of pain and dysfunction and plan a course of treatment. Swelling around the ulnar styloid and loss of wrist extension secondary to extensor carpi ulnaris subluxation indicate early wrist involvement. Dorsal wrist swelling is commonly present and can be due to radiocarpal synovitis, tenosynovitis, or a combination of the two processes. An inflamed synovial membrane surrounding the radiocarpal joint is usually tender to palpation, but there can be surprisingly little swelling on examination if it is confined only to the dorsal capsule. Swelling that is related to the joint usually does not display movement with passive motion of the digits. Tenosynovitis, however, is typically painless and nontender and moves with tendon excursion as the digits are moved.

Distal radioulnar joint involvement is confirmed with tenderness to palpation, pain, crepitation, limitation of forearm rotation, and prominence of the ulnar head indicating subluxation or dislocation. If the ulnar border of the hand and carpus are in straight alignment with the ulna, it is indicative of radial deviation and carpal supination. As mentioned previously, ulnar drift of the digits at the metacarpophalangeal joints often accompanies this. It is important to examine the function and integrity of the tendons of the digits, primarily the extensor tendons and flexor pollicis longus tendon, to identify any attritional ruptures that may be present.

Examination for provocative signs of carpal tunnel syndrome includes eliciting of Tinel sign over the carpal canal, reproduction or worsening of numbness in the digits with compression over the proximal edge of the canal at the distal wrist crease (Durkan test), and flexion of the wrist (Phalen test). A careful neurologic examination may detect decreased light touch sensibility in the thumb, index, middle, and radial aspects of the ring finger if there is advanced median nerve dysfunction. Consideration should be given to the possibility of more proximal (cervical neuropathy) causes of symptoms.

If there is significant synovitis of the radiocapitellar joint proximally, there can be posterior interosseous nerve dysfunction as well. This is manifested during the wrist and hand examination as the inability to extend the thumb and digits and, to some extent, the wrist. This finding, however, needs to be differentiated from tendon rupture or subluxation at the level of the metacarpophalangeal joints. Strength testing may be diminished because of pain from synovitis, muscle atrophy, or the inability to contract a muscle secondary to tendon rupture.

Functional Limitations

Rheumatoid patients often have shoulder, elbow, and hand involvement and an abnormal wrist, which leads to significant limitations in activities of daily living. Because the distal radioulnar joint is important in allowing functional forearm rotation and in helping to position the hand in space, advanced synovitis of this joint causing pain and fixed deformity can have a severe impact on a patient’s daily functional activity. Functional difficulties that are commonly experienced by these patients include activities of lifting, carrying, and sustained or repetitive grasp. Whereas a loss of pronation may be compensated for by shoulder abduction and internal rotation, supination loss is very difficult to compensate. This can lead to difficulty in opening doors and turning keys. Simple acts such as receiving change during shopping can be compromised by reduced supination. Furthermore, in patients with shoulder involvement, the freedom of compensatory motion at the shoulder can be severely limited, compounding the limitations imposed on the patient’s function by limitation of forearm rotation.

Diagnostic Studies

In patients in whom rheumatoid arthritis is suspected clinically, appropriate diagnostic serologic tests may include rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, HLA-B27, sedimentation rate, and anticitrulline antibody assay. These tests are performed in conjunction with a consultation by a rheumatologist or an internist experienced in the care of rheumatoid disease.

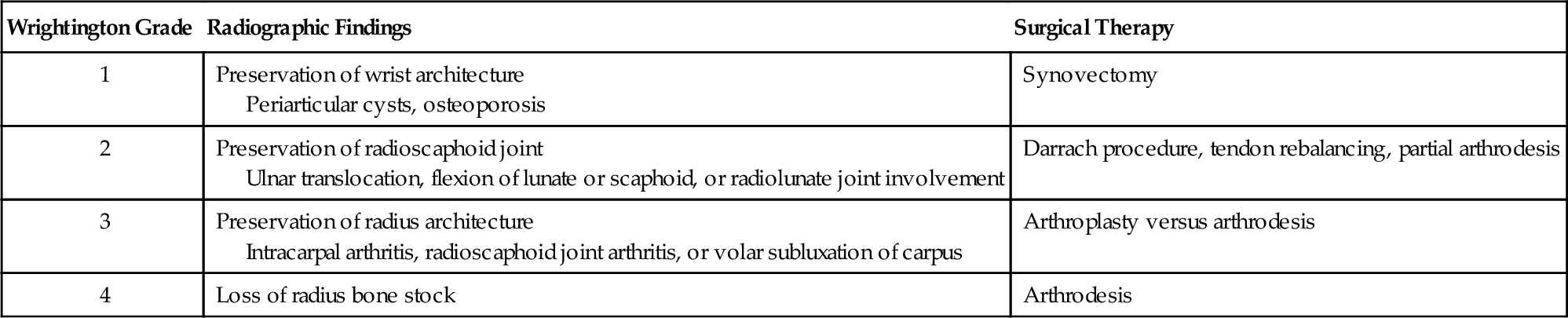

Plain radiographs of the wrist that include posterior-anterior, lateral, and oblique views allow thorough examination of the radiocarpal, midcarpal, and distal radioulnar joints. Specifically, a supinated oblique view [12] should be closely inspected for early changes consistent with rheumatoid synovitis. The earliest of these changes are symmetric soft tissue swelling and juxta-articular osteoporosis. Radiographic staging can be performed as well [13] (Table 41.1).

Table 41.1

Larsen Radiographic Staging of Rheumatoid Arthritis

| Larsen Score | Radiographic Status |

| 0 | No changes, normal joint |

| 1 | Periarticular swelling, osteoporosis, slight narrowing |

| 2 | Erosion and mild joint space narrowing |

| 3 | Moderate destructive joint space narrowing |

| 4 | End-stage destruction, preservation of articular surface |

| 5 | Mutilating disease, destruction of normal articular surfaces |

Although most patients already have a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, radiographic examination occasionally detects the earliest signs of the disease by changes in areas of the wrist where there is a concentration of synovitis. These changes include erosions at the base of the ulnar styloid, the sigmoid notch of the distal radius, and the waist of the scaphoid and isolated joint space narrowing of the capitolunate joint seen on the posteroanterior view (Figs. 41.3 and 41.4). Ulnar translocation of the carpus can also be seen on this view. The lateral radiograph can show small bone spikes protruding palmarly, usually from the scaphoid. Late radiographic changes include pancompartmental loss of joint spaces and large subchondral erosions [14] (Fig. 41.5). Although radiographic findings may not always correlate well with clinical findings, the information gained from plain radiographs can be important in influencing which procedures will be of most benefit in patients with poor medical disease control. Significant joint subluxation, bone loss, relative ulnar length, and ulnar translocation can help determine which procedure best serves a patient.

Advanced imaging techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography, are not usually helpful in evaluation or planning for surgery. Electrodiagnostic studies are recommended if neurologic symptoms are present.

Treatment

Initial

The monitored use of disease-modifying agents has dramatically improved control of the disease, especially with early, aggressive treatment. The medical treatment consists of three categories of drugs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents; corticosteroids; and disease-modifying drugs, both nonbiologic (i.e., methotrexate) and biologic (i.e., tumor necrosis factor inhibitors) [4]. The details of medical treatment are beyond the scope of this chapter.

Management of local disease depends on several factors, such as severity of disease, functional limitations, pain, and cosmetic deformity. The patient’s education, nutrition, and psychological health should be maximized.

Acutely painful, inflamed wrists are best managed with rest and immobilization and oral anti-inflammatory agents. Splints available over-the-counter may be ill-suited for this population of patients because the material cannot mold to altered anatomic contours. In such cases, a custom-made, forearm-based, volar resting splint that holds the wrist in the neutral position will provide support and comfort and is likely to be worn with greater compliance. Splints serve to stabilize joints that are subjected to subluxation forces and to improve grip when it is impaired by pain. However, splinting should be treated as a comfort measure and is not effective for preventing deformity as a result of progression of the disease [15].

Rehabilitation

Occupational therapy can provide potential pain control measures, activity modification education, custom splinting (see Initial Treatment), and exercises for range of motion tendon gliding and strengthening. A home exercise program can be developed to improve function and strength if the disease is also under adequate medical control [15].

In patients affected with local tenosynovitis of the extensor aspect and unwilling to have an injection, a trial of iontophoresis may prove beneficial. In patients with large amounts of subcutaneous adipose tissue, iontophoresis may be of limited efficacy in joints or periarticular structures. Studies on the effects of hot and cold in patients with rheumatoid arthritis show benefits in pain, joint stiffness, and strength but do not prove the superiority of one modality over the other [16]. Paraffin baths and moist heat packs are used to improve joint motion and pain, allowing increased activity tolerance. The results with paraffin baths are superior when they are combined with exercise programs [17]. Hydrotherapy can be an adjunct to many treatment programs, primarily for the purpose of decreasing muscle tension and reducing pain. Physical therapy particularly focusing on shoulder and elbow range of motion to position the hand in space may be of benefit if multiple joints are affected and symptomatic. Improvement of shoulder and elbow function is important because it is difficult to position a hand in space with a painful, stiff joint proximal to it.

Potentially the most critical role of therapy is in the postoperative period. It is then that patients particularly require monitored splinting, improvement in range of motion and strength, and edema control.

Procedures

Intra-articular cortisone injections are effective in alleviating wrist pain due to synovitis. Typically, all injections around the wrist should be done by aseptic technique with a 25-gauge, 11⁄2-inch needle and a mixture of a steroid preparation, which is injected along with 1% lidocaine. The radiocarpal joint can be injected from the dorsal aspect approximately 1 cm distal to Lister tubercle, with the needle angled proximally about 10 degrees to account for the slight volar tilt of the distal radius articular surface. This is done with the wrist in the neutral position. Gentle longitudinal traction by an assistant can help widen the joint space, which may be reduced on account of the disease.

An alternative radiocarpal injection site is the ulnar wrist, just dorsal or volar to the easily palpable extensor carpi ulnaris tendon at the level of the ulnar styloid process. The needle must be angled proximally by 20 to 30 degrees to enter the space between the ulnar carpus and the head of the ulna. It is important to ascertain that the injectate flows freely. Any resistance indicates a need to reposition the needle appropriately. Alternatively, the injection may be performed with imaging guidance, such as a mini image intensifier or ultrasound, if it is available in the office.

If a midcarpal injection is required, this is done through the dorsal aspect, under fluoroscopic guidance, with injection into the space at the center of the lunate-triquetrum-hamate-capitate region.

Injections into the carpal tunnel are usually performed at the level of the distal wrist crease with the needle introduced just ulnar to the palmaris longus, which in most patients is just palmar to the median nerve and therefore protects it at this level. In patients who do not display clinical evidence of a palmaris longus, we do not recommend carpal tunnel injections. For treatment of associated carpal tunnel syndrome, patients should be issued a wrist splint primarily for nighttime use. Steroid injection into the carpal canal is an option, but the risks of possible attritional tendon rupture need to be discussed with the patient. Thorough knowledge of local anatomy is essential before an injection into the carpal tunnel is attempted. More important, alteration of local anatomy (and therefore altered location of the median nerve) must be considered very carefully before a carpal tunnel injection.

Patients must be counseled about the postinjection period. It is not uncommon for patients to experience some increase in local discomfort for 24 to 36 hours after the injection. Use of the splint is recommended during this time, and icing of the area may also be of benefit. In our experience, most steroid injections take a few days to have a therapeutic effect. As is the case with any joint, because of the deleterious effect that corticosteroids can have on articular cartilage by transient inhibition of chondrocyte synthesis, repeated injections should be minimized if there is no radiographic sign of advanced cartilage wear, but there is no specific maximum number of injections. On the other hand, in advanced disease, when joint surgery in inevitable, there is no contraindication to repeated injections that have proved beneficial to a patient.

Surgery

The indications for operative treatment of the rheumatoid wrist include one or more of the following: disabling pain and chronic synovitis not relieved by a minimum of 4 to 6 months of adequate medical and nonoperative measures; deformity and instability that limit hand function; tendon rupture; and nerve compression. Deformity alone is rarely an indication for surgery. It is not uncommon to see patients with significant deformities demonstrate excellent function with the use of compensatory maneuvers in the absence of pain. Corrective surgery in these patients is ill-advised.

Surgical procedures can be divided into those involving bone and those involving soft tissue (Table 41.2) [18]. On occasion, a bone procedure will be combined with a soft tissue procedure in the same setting. Synovectomy involves the removal of the inflamed, thickened joint lining from the radiocarpal and distal radioulnar joints and is best performed for the painful joint that demonstrates little or no radiographic evidence of joint destruction. Tenosynovectomy involves débridement of the tissue around involved tendons in the hope of avoiding future attritional tendon ruptures. Patients best suited for these procedures have relatively good medical disease control, no fixed joint deformity, and minimal radiographic changes. If tendon rupture has already occurred, most commonly over the distal ulna, the procedure of choice is some form of tendon transfer, usually combined with resection of the ulnar head (Darrach procedure) [19]. Repair is not indicated or possible in most cases because of the poor tissue quality and extensive loss of tendon tissue in the zone of rupture. Depending on the number of tendons ruptured, it is possible to transfer the ruptured distal tendon into a neighboring healthier tendon or to transfer a more distant tendon, such as the extensor indicis proprius or superficial flexor tendon, into the affected tendon. The distal end of a ruptured extensor tendon may also be sutured to its unaffected neighboring extensor in some cases.

Bone procedures include resection arthroplasty, resurfacing arthroplasty, and limited or complete wrist fusions. Resection arthroplasty, such as the Darrach procedure, in which the distal ulna is resected, is beneficial in the setting of distal ulnar impingement on the carpus or for distal radioulnar joint disease. It may also prevent tendon rupture of the extensor tendons on the dorsum of the ulnar head. However, it may further ulnar translocation of the carpus and therefore should be combined with a radiolunate arthrodesis in patients with weak ligamentous support where this is a concern (see later). An alternative treatment for debilitating distal radioulnar joint pain is the Sauvé-Kapandji procedure, in which the distal ulna is fused to the distal radius along with a distal ulnar osteotomy. This osteotomy is essentially a resection of a small segment of bone proximal to the fused distal radioulnar joint to construct a “false joint,” or pseudarthrosis, through which the patient may be able to rotate the forearm. Excellent pain relief has been demonstrated in rheumatoid patients with this procedure [20,21]. Although this procedure is better at preventing ulnar translocation, nonunion of the arthrodesis site is an issue, particularly in rheumatoid arthritis patients with poor bone stock.

To address the radiocarpal joint, two options exist: wrist resurfacing arthroplasty or fusion. The arthroplasty requires the resection of a portion of the distal radius and carpus and insertion of an implant usually made of a metallic component with a polyethylene spacer. It is generally restricted to patients with low functional demands who have bilateral rheumatoid wrist disease and require some motion in one wrist if the other is fused. It is most effective in patients who have good bone stock, relatively good alignment, and intact extensor tendons. The benefits of the arthroplasty include maintenance of range of motion and pain relief. Although some studies show promising results with wrist arthroplasty [22–26], other long-term studies show loosening in half to two thirds of the population [27,28], with removal in 25% to 40%.

Fusion, or arthrodesis, procedures to eliminate pain due to significantly degenerative joints are well described [29–34]. However, depending on the nature of the fusion, these lead to a partial or complete loss of wrist motion. Limited fusions are described of the radiolunate joint (Chamay arthrodesis) or the radioscapholunate joint. The potential benefit of limited fusions is some sparing of wrist motion, which can occur through the articulations that remain unfused, and this sparing of some motion can be critical to overall function in this group of patients. In each of these procedures, the midcarpal joint must be well preserved.

Total wrist fusion is a reliable, safe, and well-established procedure for relieving pain and providing a stable wrist that improves hand function but without range of motion of the radiocarpal joint [29,30,32]. Success rates of 65% to 85% have been shown in terms of eliminating or significantly improving wrist pain [32]. For advanced wrist rheumatoid disease, it has become the most common bone procedure. Fusion can be accomplished either with a contoured dorsal plate fixed to the wrist by screws or with one or more large intraosseous pins placed across the wrist (Fig. 41.6). The intraosseous pins are usually placed through the second or third metacarpal or through both, across the wrist into the medullary canal of the radius. Ideally, the wrist is fused in slight extension to allow improved grip strength. However, if both wrists are to be fused, one may consider fusing one in slight flexion and the other in slight extension to allow functional differences [5]. High rates of fusion and a 15% rate of symptomatic hardware removal have been described [31]. Consideration of the quality of the overlying soft tissue is necessary in deciding on a fusion technique, as more soft tissue dissection is necessary for the plate and may result in wound complications.

If significant median nerve compression exists, an extended open carpal tunnel release with flexor tenosynovectomy is typically performed through a palmar incision.

Potential Disease Complications

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic, progressive disease that can cause significant upper extremity disability at many locations by stiffness or instability from the shoulder to the hand. If wrist involvement becomes advanced, this contributes to problems with motion, pain, stiffness, and nerve compression. Extensor and flexor tendon rupture is a common scenario in rheumatoid disease and can complicate management. During the course of their disease, most patients with rheumatoid disease will lose some functional capacity, and about half will have disabling disease that requires significant physical dependence on adaptive measures for performance of the activities of daily living. Occupational therapists and social workers play roles in obtaining and using aids and appliances, such as special grips and alterations of household appliances, to maximize the patient’s function.

Potential Treatment Complications

Systemic complications from the medical treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with current disease-modifying agents are beyond the scope of this chapter. Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications have well-known side effects that can affect the cardiac, gastric, renal, and hepatic systems. Intra-articular corticosteroid injections involve a very small risk of infection as well as cumulative cartilage injury from repeated exposure to steroid.

Surgical complications can result from wound healing problems, infection, neurovascular injury, recurrent synovitis, recurrent tendon rupture, persistent joint instability, and implant loosening or failure. To some extent, meticulous surgical technique and judicious management of medications affecting wound healing and immunity, such as methotrexate and systemic steroids, may reduce the frequency of complications.