CASE 41 Postoperative Acute STEMI

Cardiac catheterization

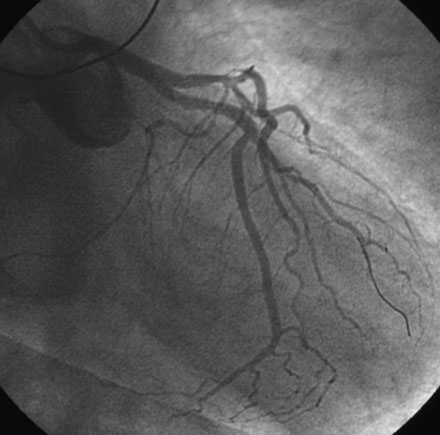

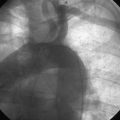

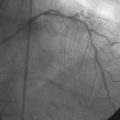

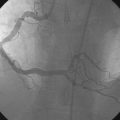

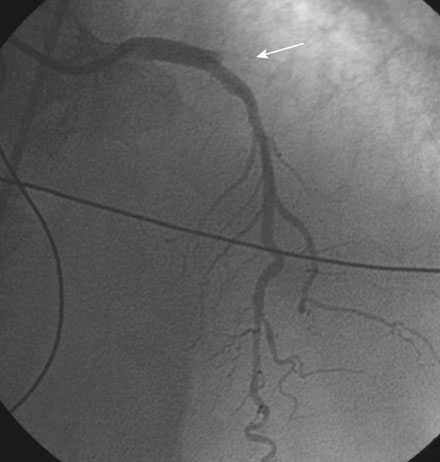

The right coronary artery was small and nondominant, with luminal irregularities (Figure 41-1). The left anterior descending artery (LAD) was patent with a long tubular stenosis of mild severity just prior to the previously placed stent. The stent itself was widely patent. The circumflex artery was occluded at the ostium within the previously placed stent, consistent with late stent thrombosis (Figure 41-2 and Video 41-1). Anticoagulation was achieved with heparin and abciximab, and a 0.014 inch guidewire was advanced easily through the thrombosed stent and into the distal circumflex. The lesion was dilated with a 3.0 mm diameter by 15 mm long compliant balloon with return of flow to the artery, but with residual thrombus (Figure 41-3 and Video 41-2). The operator felt there was residual stenosis and attempted to dilate the lesion with a 3.0 mm diameter by 15 mm long noncompliant balloon. However, the balloon would not advance into the stented segment. A 2.5 mm diameter by 15 mm long noncompliant balloon was advanced easily into the lesion and inflated to high pressure. Subsequently, the 3.0 mm diameter noncompliant balloon passed easily and the lesion was dilated multiple times with high-pressure inflations. The final angiogram revealed minimal thrombus within the stented segment and the artery had TIMI-3 flow (Figure 41-4 and Video 41-3).

FIGURE 41-1 Right coronary angiography revealed a small, nondominant right coronary artery with luminal irregularities.

FIGURE 41-2 There was occlusion of the left circumflex artery within the previously placed stent (arrow).

Discussion

Approximately 5% of patients undergoing stent placement require noncardiac surgery within the following year.1 The current guidelines recommend postponement of noncardiac surgery for at least 6 months following bare-metal stent placement and for at least 1 year following drug-eluting stent placement.2,3 However, there appears to be some degree of later risk with cessation of antiplatelet therapy and/or with surgery that has not been well defined. Several retrospective studies have now addressed the risk of stent thrombosis at several time points after stent implantation. With increasing time from implantation, risk of thrombosis decreases; however, the incidence of stent thrombosis was still significant beyond 3 months for bare-metal stents and beyond 12 months for drug-eluting stents. Over half of the patients experiencing an event were on single or dual antiplatelet therapy up to the time of the procedure, demonstrating that many events may not be preventable even with continuation of antiplatelet therapy.4,5 Several factors have been found to correlate with adverse events, including stent thrombosis, in the perioperative period, including: myocardial infarction within 30 days of surgery, preoperative heparin use, emergency surgery, longer treated lesion length, lower preoperative ejection fraction, shorter time following stenting, and use of aspirin or clopidogrel 24 hours prior to surgery.

Stent thrombosis in the perioperative period also presents challenges in terms of anticoagulation strategies.6 Use of antithrombotic agents during the procedure in combination with antiplatelet agents following the procedure significantly increases the risk of major bleeding.

Due to the devastating implications of stent thrombosis, the possible need for surgery in the upcoming year should be clearly ascertained by the operator when determining the type of stent to be implanted, or whether revascularization is even necessary prior to surgery. In the absence of high-risk features, such as left main disease, unstable angina, or severe cardiomyopathy, the incidence of perioperative myocardial infarction is not changed by preoperative revascularization. Thus, in stable patients, revascularization can generally be safely delayed until after the perioperative period.7

1 Vicenzi M.N., Ribitsch D., Luha O., et al. Coronary artery stenting before noncardiac surgery: more threat than safety? Anesthesiology. 2001;94:367-368.

2 Fleisher L.A., Beckman J.A., Brown K.A., et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: a report of the ACC/AHA task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50e:e159-e241.

3 Grines C.l., Bonow R.O., Casey D.E., Jr, et al. Prevention of premature discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery stents: a scientific advisory form the AHA, ACC, SCAI, and ACS, and ADA, with representation from the ACP. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:734-739.

4 van Kujik J.P., Flu W.J., Schouten O., et al. Timing of surgery after coronary artery stenting with bare metal or drug-eluting stents. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1229-1234.

5 Brilakis E.S., Banerjee S., Berger P.B. Perioperative management of patients with coronary stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2145-2150.

6 Anwaruddin S., Askari A.T., Saudye H., et al. Characterization of post-operative risk associated with prior drug-eluting stent use. J Am Coll Cardiol Interv. 2009;2:542-549.

7 Poldermans D., Schouten O., Vidakovic R., et al. A clinical randomized trial to evaluate the safety of a noninvasive approach in high-risk patients undergoing major vascular surgery: the DECREASE-V pilot study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1763-1769.