CHAPTER 40

Wrist Osteoarthritis

Anna Babushkina, MD; Chaitanya S. Mudgal, MD, MS (Orth), MCh (Orth)

Definition

Osteoarthritis of the wrist refers to the painful degeneration of the articular surfaces that make up the wrist due to noninflammatory arthritides. It commonly affects the joints between the distal radius and the proximal row of carpal bones. Symptoms include pain, swelling, stiffness, and crepitation. Radiographs will reveal different degrees of joint space narrowing, cyst formation, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophyte formation.

Secondary osteoarthritis resulting from post-traumatic conditions, as can be seen after distal radius fractures, carpal fractures, and carpal instability, is the most common form [1]. Primary osteoarthritis in the wrist is rare. The Framingham study showed a 9-year incidence of only 1% of radiographically significant wrist osteoarthritis in women and 1.7% in men. These rates are significantly lower than the rates of thumb basal joint osteoarthritis (30%), distal interphalangeal joint arthritis (28%-35% in patients older than 40 years), and radiographic hand osteoarthritis in patients 80 years and older (90%-100%) [2]. Rare conditions that may cause wrist osteoarthritis include idiopathic osteonecrosis of the lunate (Kienböck disease) and the scaphoid (Preiser disease). Distal radius fractures that have healed inappropriately (malunited) can also be the cause (Fig. 40.1). In considering malunited fractures of the distal radius, abnormal parameters that have been shown to be associated with wrist arthritis include the following: on an anteroposterior radiograph, an intra-articular step-off of more than 2 mm and radial shortening of more than 5 mm; and on the lateral radiograph, a dorsal angulation of more than 10 degrees [3–5].

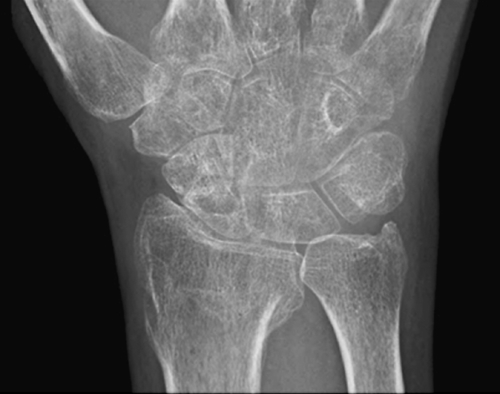

Carpal fractures that fail to heal, particularly of the scaphoid, can also be the cause of arthritis [6]. This bone is predisposed to nonunions biologically because of its fragile vascular supply and biomechanically on account of the shear forces it encounters [7,8]. Other factors associated with nonunions include fracture displacement, fracture location, and delay in initiation of treatment [9,10]. Features of a scaphoid nonunion that appear to be associated with arthritis are the displacement of the cartilaginous surfaces and the loss of carpal stability [11,12]. Both of these lead to abnormal loading of the cartilage and consequently to ensuing arthritis. This pattern of arthritis is known as scaphoid nonunion advanced collapse (SNAC) (Fig. 40.2).

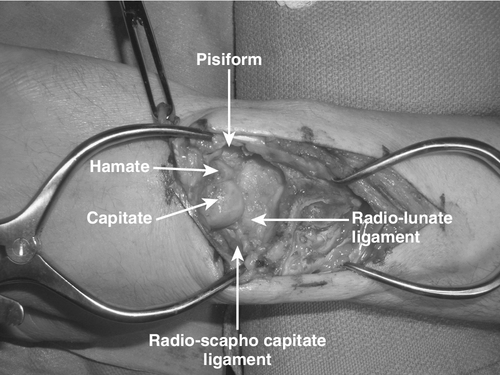

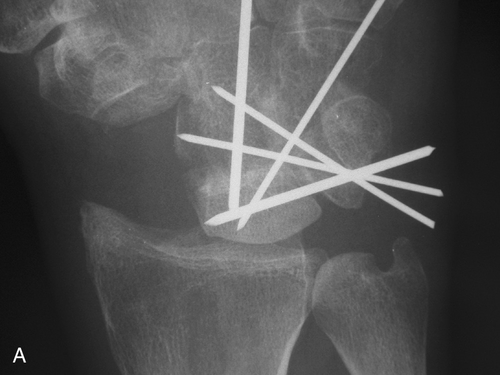

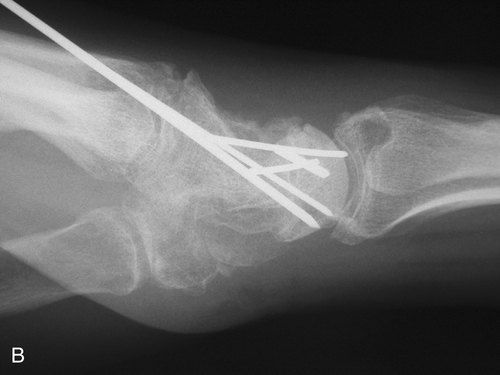

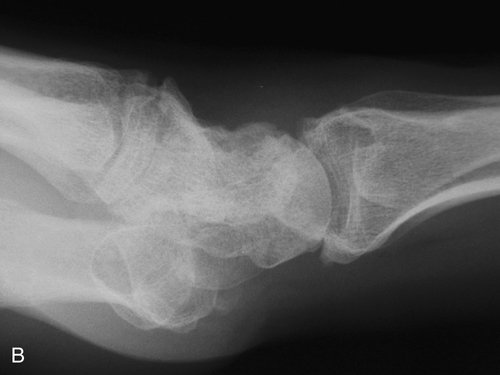

Carpal instability can also result in uneven loading of the articular surfaces and subsequent arthritis [13] (Figs. 40.3 and 40.4). The most common form of carpal instability is scapholunate dissociation [14]. It consists of a disruption of the interosseous ligament between the scaphoid and lunate. The resultant abnormal biomechanics lead to abnormal loading and subsequent arthritis, a pattern known as scapholunate advanced collapse [1] (SLAC).

Symptoms

Wrist pain is the presenting symptom in the overwhelming majority of patients. For the most part, this pain is of insidious onset, although many patients will recall a particular event that brought it to their attention. It is diffusely located across the dorsum of the wrist. It may be activity related and may bear little correlation to radiographic findings. Patients may also report inability to do their daily activities because of weakness, but on further questioning, this weakness is often secondary to pain.

Another presenting symptom is stiffness, particularly in flexion and extension of the wrist. Pronation and supination are usually not affected, unless the arthritic process is extensive and also involves the distal radioulnar joint. Motion may also be associated with a clicking sensation or with audible crepitation.

Complaints about cosmetic deformity are also common, particularly after distal radius fractures that have healed with an inappropriate alignment. Swelling is also commonly noted by the patients. This swelling is essentially a representation of the malunited fracture, but in patients with advanced arthritis irrespective of the etiology, it may represent synovial hypertrophy or osteophyte formation. In this situation, the swelling tends to be located in the dorsoradial region of the wrist (Fig. 40.5).

Physical Examination

Examination of the wrist includes a thorough examination of the entire upper limb. Comparison with the opposite side is useful to determine the degree of motion loss, if any. In wrist osteoarthritis, the most obvious finding may be loss of motion. Normal range of motion includes approximately 80 degrees of flexion, 60 degrees of extension, 20 degrees of radial deviation, and 40 degrees of ulnar deviation [15]. Comparison with the opposite side, if it is not involved, is useful to determine the degree of motion loss.

The wrist is palpated for evidence of cysts or tenderness. Tenderness just distal to Lister tubercle may be a sign of pathologic change at the scapholunate joint, including scapholunate dissociation, Kienböck disease, or synovitis of the radiocarpal joint. Tenderness at the anatomic snuffbox may indicate a scaphoid fracture or nonunion and, in early SNAC wrists, may be the site of radioscaphoid degeneration. In the presence of pancarpal arthritis, the tenderness is usually diffuse.

Provocative maneuvers should also be performed to check for signs of carpal instability. The scaphoid shift test of Watson evaluates for scapholunate instability [16]. In this test, the examiner places a thumb volarly on the patient’s scaphoid tubercle, and the rest of the fingers wrap around the wrist to lie dorsally over the proximal pole of the scaphoid. As the wrist is taken from ulnar deviation to radial deviation, the thumb will apply pressure on the scaphoid tubercle and force the scaphoid to sublux out of its fossa dorsally in ligamentously lax patients as well as in those with frank scapholunate instability. Once pressure from the thumb is released, the scaphoid will then shift back into its fossa. This finding is best demonstrated in those who have ligamentous laxity or those with recent injuries. Patients who have chronic injuries often develop sufficient fibrosis to prevent subluxation of the scaphoid out of its fossa. However, they often still have pain that is reproduced with this maneuver. Comparison with the unaffected side is essential, especially if the patient has evidence of generalized ligamentous laxity.

The strength of the abductor pollicis brevis is tested by asking the patient to palmar abduct the thumb against resistance, and it should be compared with the opposite side. Similarly, the strength of the first dorsal interosseus should be checked by asking the patient to radially deviate the index finger against resistance. These tests evaluate for motor deficits of the median nerve and ulnar nerve, respectively. Sensation should also be compared with the opposite side. Whereas static two-point discrimination is an excellent way to test sensation in the office, a more precise evaluation of early sensory deficits can be performed by graduated Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments. Frequently, this test requires a referral to occupational therapists who perform it.

Functional Limitations

The majority of the limitations in wrist arthritis arise from a lack of motion. A range of motion from 10 degrees of flexion to 15 degrees of extension is required for activities involving personal care [17]. The loss of motion mainly affects activities of daily living such as washing one’s back, fastening a brassiere, and writing. Eating, drinking, and using a telephone require 35 degrees of extension. However, learned compensatory maneuvers can allow most activities of daily living to be accomplished with as little as 5 degrees of flexion and 6 degrees of extension [18].

Diagnostic Studies

The initial evaluation of the arthritic wrist includes standard posteroanterior, lateral, and pronated oblique radiographs. In the posteroanterior view, any evidence of arthritis between the radius and proximal row of carpal bones or between the proximal and distal rows should be noted. Radiographic features that indicate an arthritic process include reduction or loss of joint space, osteophyte formation, cyst formation in periarticular regions, and loss of normal bone alignment (see Figs. 40.2 to 40.4).

Injury to the scapholunate ligament is evidenced by a space between the scaphoid and the lunate greater than 2 mm and a cortical ring sign of the scaphoid [14]. Sclerosis or collapse of the lunate is consistent with Kienböck disease [19]. The lateral view can reveal signs of carpal instability, such as a dorsally or palmarly oriented lunate. An angle between the scaphoid and the lunate in excess of 60 degrees is also consistent with scapholunate dissociation. The oblique view will often demonstrate the site of a scaphoid nonunion. Although it may be possible to make a diagnosis of scapholunate dissociation on plain radiographs, some patients can often have bilateral scapholunate distances and angles in excess of normal limits. It is therefore critical to obtain contralateral radiographs before a diagnosis of scapholunate injury is made.

Patterns of arthritic progression in SLAC and SNAC wrists have been classified into three stages. In a SLAC wrist, stage 1 involves arthritis between the radial styloid and the distal pole of the scaphoid; stage 2 results in reduction or loss of joint space between the radius and the proximal pole of the scaphoid (see Fig. 40.3), and stage 3 indicates capitolunate degeneration with proximal migration of the capitate between the scaphoid and lunate (see Fig. 40.4). In a SNAC wrist, stage 1 and stage 3 are similar to those in a SLAC wrist. However, in stage 2, there is degenerative change between the distal pole of the scaphoid and capitate (see Fig. 40.2).

Other imaging modalities are not necessary for the diagnosis of osteoarthritis. Computed tomography is sometimes used to evaluate the alignment of the scaphoid fragments in cases of nonunion and the amount of collapse of the lunate in Kienböck disease. Magnetic resonance imaging is occasionally used to evaluate the vascularity of the scaphoid proximal pole and lunate in scaphoid nonunions and Kienböck disease, respectively [19,20]. Wrist arthroscopy offers the optimal ability to assess the condition of the articular cartilage; however, this assessment can be made from plain radiographs or at the time of surgical reconstruction of the wrist.

Treatment

Initial

Osteoarthritis of the wrist is a condition that has usually been present for a significant amount of time. However, it is not uncommon for symptoms to be of a short duration, and they can often be manifested after seemingly trivial trauma. It is important for the physician to establish good rapport with the patient during several visits so that the pathophysiologic changes of the process can be emphasized to the patient. This becomes even more important in situations involving workers’ compensation or litigation or both. It is also important for the patient to understand that the condition cannot be reversed and that the symptoms are likely to be cyclic. Patients must understand that over time, the condition may worsen radiographically; however, it is impossible to predict the rate of progression or severity of symptoms that might ensue.

Many patients present with symptoms of wrist osteoarthritis that are not severe enough to be limiting but enough to be noticed. These patients are often looking for reassurance about their condition. If they are able to do all the activities that they want to do, intervention is not needed. They should not refrain from doing their activities in fear that they may accelerate the condition; there is no scientific evidence to substantiate this concern. This approach offers the least amount of risk to the patient.

Other patients may prefer to have some symptom reduction, particularly during episodes of acute worsening, despite some inconvenience or small risks. An over-the-counter wrist splint with a volar metal stabilizing bar (cock-up splint) can be a small inconvenience; however, by virtue of immobilizing the wrist, it can provide great symptom relief during daily activities. This metal bar can be contoured to place the wrist in the neutral position rather than in extension, as most splints of this nature tend to do. The neutral position appears to be better tolerated by patients and affords better compliance with splint wear. Both over-the-counter and custom leather splints have been shown to relieve pain and to improve function and grip strength. Custom splints, however, provided more of these improvements and were better liked by patients in one study [21]. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can also provide significant pain relief, particularly during periods of acute exacerbation of symptoms. A long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is not indicated. Periodic application of ice, especially during periods of acute symptom exacerbation, can be of help. On occasion, in patients with radioscaphoid arthritis (SNAC), inclusion of the thumb in a custom-made orthoplast splint may provide better pain relief. Use of magnetic and copper bracelets has not been shown to be effective in clinical trials [22].

Rehabilitation

Once the acute inflammation phase has passed, most patients are able to resume most activities. Some may complain of persistent lack of motion or strength. These patients may benefit from a home exercise program for range of motion and strengthening directed by an occupational therapist. Modalities such as fluidized therapy may help with range of motion. Static progressive splinting is usually not recommended to improve range of motion because there is often a bone block to motion. It is always important to understand that therapy itself may worsen symptoms, especially passive stretching exercises. Active range of motion and active-assisted range of motion exercises are better tolerated by patients, and some patients may be better off without any formal rehabilitation.

Procedures

Nonsurgical procedures, including corticosteroid injections, may be indicated for wrist osteoarthritis, although they appear to have a greater use in crystalline and inflammatory arthritides. Hyaluronan injections for osteoarthritis have been studied in other joints, including the thumb carpometacarpal joint, with beneficial results; however, their use in the wrist is still considered experimental [23]. Typically, all injections around the wrist should be done by aseptic technique with a 25-gauge, 11⁄2-inch needle and a mixture of a nonprecipitating, water-soluble steroid preparation that is injected along with 2 mL of 1% lidocaine.

The radiocarpal joint can be injected from the dorsal aspect approximately 1 cm distal to Lister tubercle, with the needle angled proximally about 10 degrees to account for the slight volar tilt of the distal radius articular surface. This is done with the wrist in the neutral position. Gentle longitudinal traction by an assistant can help widen the joint space, which may be reduced on account of the disease. An alternative radiocarpal injection site is the ulnar wrist, just palmar to the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon at the level of the ulnar styloid process. With strict aseptic technique, a 25-gauge, 11⁄2-inch needle is inserted into the ulnocarpal space, just distal to the ulnar styloid, just dorsal or volar to the easily palpable tendon of the extensor carpi ulnaris. The needle must be angled proximally by 20 to 30 degrees to enter the space between the ulnar carpus and the head of the ulna. It is important to ascertain that the injectate flows freely. Any resistance indicates a need to reposition the needle appropriately. Alternatively, the injection may be performed by fluoroscopic guidance with the help of a mini image intensifier, if one is available in the office.

If a midcarpal injection is required, this is done through the dorsal aspect, under fluoroscopic guidance, with injection into the space at the center of the lunate-triquetrum-hamate-capitate region.

Surgery

The goal of surgery in an osteoarthritic wrist is pain relief. Surgical procedures for osteoarthritis can be divided into motion-sparing procedures and fusions (arthrodesis). However, even motion-sparing procedures often result in significant loss of motion. This is very important in patients who have almost no motion preoperatively. These patients will not benefit from motion-sparing procedures and are better served with total wrist fusions. The decision to proceed with surgery should not be made until nonsurgical means have been tried for an adequate time, which usually amounts to a period of 3 to 6 months. In some patients who are going to have a total wrist fusion, before a decision is made about surgery, it is useful to apply a well-molded fiberglass short arm cast for 2 weeks to accustom the patient to the lack of wrist motion.

Motion-sparing procedures include proximal row carpectomy, total wrist arthroplasty, and limited intercarpal fusions with scaphoid excision. The excision of the scaphoid is essential because 95% of wrist arthritis involves the scaphoid [1]. Proximal row carpectomy involves removal of the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum. The capitate then articulates with the radius through the lunate fossa (Fig. 40.6). Wrist stability is maintained by preserving the volar wrist ligaments. As a prerequisite for this procedure, the lunate fossa of the radius and the articular surface over the head of the capitate must be healthy and free of degenerative change (Fig. 40.7). The main advantage of this procedure is that it does not involve any fusions. After a short period of postoperative casting, patients are allowed to start moving the wrist as early as 3 weeks after surgery. Most people are able to attain a flexion-extension arc of 60 to 80 degrees and 60% to 80% of the grip strength of the uninvolved side [24,25] (Fig. 40.8). This procedure is appropriate for the early stages of SLAC and SNAC arthritis. Some surgeons have attempted to extend the indications for proximal row carpectomy in the setting of capitate head cartilage loss or lunate fossa arthrosis by suggesting interposition of soft tissue allograft or autograft or osteochondral autograft to the capitate from the excised carpal bones [26–28].

Indications for total wrist arthroplasty have expanded from end-stage rheumatoid arthritis to include post-traumatic osteoarthritis, end-stage primary osteoarthritis, and Kienböck disease. Patients are discouraged from heavy lifting after arthroplasty surgery but can otherwise return to full activity after a 2- to 3-month period of splinting in 30 to 40 degrees of extension to prevent flexion contracture. Short-term results have been encouraging with significant pain relief, maintenance of grip strength of 60% of the uninvolved side, preservation of motion, and even an increase in radial deviation in one study [29,30]. Total wrist arthroplasty is not recommended in people younger than 50 years, heavy laborers, or those dependent on walking aids.

The most common limited intercarpal fusion is known as the four-corner or four-bone fusion. It involves creating a fusion mass between the lunate, triquetrum, capitate, and hamate. The scaphoid is excised. The prerequisite for this procedure is an intact joint between the radius and the lunate. A theoretical advantage of this procedure over a proximal row carpectomy is that it maintains carpal height, leading to a better grip strength (Fig. 40.9). However, this has not been shown to be the case in larger studies comparing these two procedures. The flexion-extension arc of wrist motion is also not significantly different between these two procedures [31]. Theoretical disadvantages of a four-corner fusion include protracted immobilization until fusion is confirmed (usually 8 weeks) and the possibility of needing a secondary operative procedure to remove hardware (Fig. 40.10). This procedure is also appropriate for the early stages of SLAC and SNAC arthrosis.

Patients with severe arthrosis that involves not only the radiocarpal joint but also the joint between the proximal and distal carpal rows (midcarpal joint) are better served with total wrist fusion. This procedure is also beneficial in patients who present preoperatively with minimal or no wrist motion. It involves a fusion between the radius, proximal row, and distal row of carpal bones. The wrist is protected with a splint for 4 to 6 weeks. Most patients are able to attain a grip strength that is 60% to 80% of the opposite side [32]. A successful fusion abolishes the flexion-extension arc of wrist motion and, more important, can be effective in obtaining pain relief. However, the lost motion makes it difficult for patients to position the hand in tight spaces and can affect perineal care [31]. In these patients, the loss of motion does not appear to have an adverse functional impact because most of these patients have significant reduction of motion at the time of presentation. The pain relief provided by this procedure, however, can have a positive impact on functional outcome to a significant degree. Pronation and supination are unaffected. This procedure is appropriate for the advanced stages of SLAC and SNAC arthritis (Fig. 40.11).

Wrist denervation, which does not address the osteoarthritis directly but acts as a palliative option, was proposed in 1965 by Wilhelm [33]. The procedure involves ablation of sensory branches of local nerves to the wrist capsule without addressing any bone deformity. Since then, others have modified the approach and have also suggested partial denervations. Pain relief can be as high as 80% to 100%. The major benefit of denervation is that all the other options remain at the surgeon’s disposal should bone procedures become necessary. Despite early concerns, the wrist does not undergo Charcot arthropathy after denervation [34,35].

Potential Disease Complications

Wrist osteoarthritis that progresses to advanced stages results in severely painful limitation of motion. Patients are unable to do their activities of daily living because any load across the arthritic wrist joint results in pain. The pain and stiffness can also inhibit the ability of the patient to position the hand in space. Rarely, osteophytes occurring over the dorsal aspect of the distal radius and the distal radioulnar joint can cause attritional ruptures of extensor tendons.

Potential Treatment Complications

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medicines carry risks to the cardiovascular, gastric, renal, and hepatic systems. For these reasons, these medications are typically used for short periods. Surgery exposes the patient to significant risks from anesthesia, infection, nerve injury, and tendon injury. Fusions carry the risk of nonunion and malunion as well as that of hardware complications, such as prominence of the hardware, tendon irritation, and metal sensitivity. Motion-sparing procedures can eventually lead to further degenerative disease (Fig. 40.12) and in the presence of symptoms may require further surgery, which most commonly consists of a total wrist fusion. Total wrist arthroplasties can be complicated by infection, loosening, wound issues, hardware failure, instability, dislocation, tendon rupture, and impingement, with complication rates varying from 9% to 75%. Survival rates of total wrist arthroplasty in a Norwegian study ranged from 57% to 78% at 5 years and were as high as 71% at 10 years, depending on the implant and preoperative diagnosis [30].