CHAPTER 4 Treatment Adherence

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Studies suggest that rates of nonadherence with psychiatric treatment are alarmingly high (24% to 90%). In a large meta-analysis, with a pooled sample of over 23,000 patients, the mean rate of nonadherence was 26%.1

Rates of treatment adherence vary depending on the population, the diagnosis, and the pharmacological intervention. Particularly high rates of treatment nonadherence occur among those with psychotic disorders. This was made clear in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) investigation, which reported high rates of treatment discontinuation (74%) among the intent-to-treat group of 333 patients, within 4 months.2 A majority of patients were unable to remain in treatment, largely due to inadequate efficacy of treatment or to intolerable side effects. Reasons for nonadherence are multiple, complex, and varied.

Data on nonadherence include the following: only 45% of patients referred for psychotherapy from a general hospital psychiatry outpatient department showed up for one or more appointments3; nonattendance rates for patients with scheduled medical appointments are high (19% to 28%); nonadherence with medical recommendations accounts for 5% to 40% of hospital readmissions; medication doses are delayed or omitted by 30% to 50% of patients; patients with chronic diseases take their medications as prescribed only half of the time; 20% of patients stop filling their prescriptions within 1 month of their issue; approximately one-fourth of patients do not inform their physician about having stopped their antidepressant medications4; and in a follow-up study of inpatients with suicidal ideation, 52% of patients were nonadherent with use of medications at 12 weeks.5

CLINICAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACT OF ADHERENCE AND NONADHERENCE

Clinical outcomes are directly related to treatment adherence, which in turn is related to resource utilization and to the economic burden of mental illness. Adherence with psychiatric treatments is associated with better outcomes, a lower relapse rate, improved adherence with treatment regimens for nonpsychiatric illness, and lower rates of hospitalization.6–8 Nonadherence has been associated with a greater risk of psychiatric hospitalization, use of emergency services, arrests, violence, victimizations, lower mental function, lower life satisfaction, and more prevalent use of substances.9 Rates of suicidal ideation are significantly greater among patients who are treatment nonadherent following hospitalization.5

Given the clinical impact of treatment nonadherence, the economic burden incurred through nonadherence is significant. Data derived from the Global Burden of Disease Study conducted by the World Health Organization, the World Bank, and Harvard University revealed that mental illness, including suicide, accounts for over 15% of the burden of disease in countries such as the United States.10 Additionally, since major depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide among persons age 5 or older, adherence to treatment can reduce the economic burden of mental illness.

RISK FACTORS AND PREDICTORS OF TREATMENT NONADHERENCE

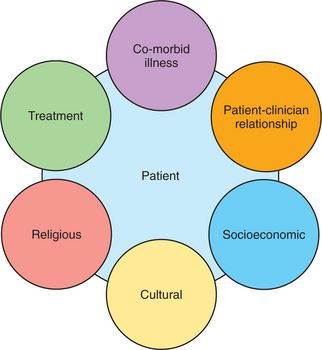

The reasons for treatment nonadherence are incompletely understood; however, they are undoubtedly multiple, com-plex, and varied. Any effort to understand this multifactorial challenge must include consideration of the elements in Figure 4-1 and Table 4-1.

Affective Disorders

Studies of treatment adherence in those with depression demonstrate that adherence is highest when the perceived need for medication is greatest and the harmfulness of medication is low.11 In addition, a patient’s skepticism about the efficacy of antidepressant medications predicts early discontinuation of them.12 Reasons for nonadherence include discomfort about psychiatric diagnoses, denial of the illness, problematic side effects, fears of dependency, and the belief that medications were unhelpful following resolution of the acute phase of illness.13

In a study of African American and Caucasian patients with bipolar I disorder, more than half of all patients were either fully or partially nonadherent with medications, 4 months after an episode of acute mania.14 More than 20% denied having bipolar disorder, and they cited side effects of medications as contributing to their nonadherence. African Americans (more often than Caucasians) cited the fear of addiction and medication as a symbol of illness as reasons for nonadherence, which suggests that different cultures or ethnic groups may differ in their reasons for nonadherence.

Among patients with bipolar disorder, insight into treatment has been positively correlated with medication adherence, and adherence at the time of remission predicted adherence at one year.15

Psychotic Disorders

Patients with schizophrenia have been intensively studied regarding their adherence to treatment, in large part because of the risks associated with treatment nonadherence. One post-hoc, pooled analysis of 1,627 patients with psychosis treated with atypical antipsychotics reported that 53% of the patients discontinued their medication soon after treatment began because of their perceptions of poor response and worsening symptoms (36%), followed by poor medication tolerability (12%).16 Other reasons for nonadherence include a lack of insight, positive symptoms, younger age, male gender, a history of substance abuse, unemployment, and low social function.1,17

For patients with first-episode psychosis, the likelihood of becoming medication nonadherent is greater in those who believe that treatment is not important or who believe that medications are of low benefit. High levels of positive symptoms at baseline, a lack of insight at baseline, and alcohol or drug misuse at baseline predict nonadherence.18,19

Among patients with schizophrenia, patient-reported reasons for nonadherence include feeling stigmatized by taking medications, having adverse drug reactions, being forgetful, and having a lack of social rapport. Other barriers to adherence include use and abuse of drugs and alcohol, a higher Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale score, and a higher mean Barnes Akathisia Score.20 Factors that predict or enhance treatment adherence include feelings that the drug improves the illness, appreciating the time and commitment of staff, developing social support and engagement without a focus on medication, and invoking a partnership model of the therapeutic relationship.21,22

STRATEGIES TO ASSESS AND ENHANCE ADHERENCE

Numerous qualitative and quantitative studies have investigated adherence-enhancing strategies. In general, strategies that employ purely educational tactics are less successful, whereas studies with combined educational, behavioral, and affective components have moderate improvements in adherence and concurrent improvements in clinical outcome.23,24 The majority of studies indicate that a collaborative approach, with both patients and clinicians involved in the decision-making, is most effective.14

Strategies for the assessment of adherence are largely based on patient self-report. Other methods include reports by significant others, prescription refill records, pill counting, determination of blood levels, and a urine analysis of medication.25 However, all of these assessment tools are flawed. For example, recall bias affects self-report and significant other report. A patient may exaggerate the degree of treatment adherence, and a report by a significant other can be compromised by how closely he or she monitors medication administration. Pill counts are often affected by free samples and by leftover pills from other prescriptions. Blood levels vary significantly from individual to individual; relying on pharmacokinetic profiles does not confirm daily administration.

While numerous strategies to increase adherence have been studied, it is difficult to compare such studies (given the absence of standards for the evaluation of adherence). For example, one study employed self-report and defined adherence as taking medications on 70% of days, whereas another study used prescription records and pill counts and defined adherence more stringently (as 90% adherence to medications and coming to 100% of appointments). Nonetheless, some strategies that enhance adherence include the following: educating patients with a focus on building insight, on the need for treatment and on the benefits of treatment16,20; increasing the frequency of visits26; using a depot injection of antipsychotic medications27,28; limiting the number of daily doses29; choosing medications with tolerable side effects; and using actual risk percentages (in addition to semantic information) when discussing the risks of adverse events.30

PRACTICAL ADVICE FOR TREATING CLINICIANS

The Initial Adherence Assessment

In judging the treatment compliance status of their patients, clinicians underestimate the frequency and magnitude of nonadherence.31 Nonetheless, the clinician is advised to complement evidence-based knowledge with empiric experience.

During a routine evaluation, adherence can be assessed in a variety of ways (Table 4-2).

| Component of History | Comment/Inquiry |

|---|---|

| History of present illness | Has nonadherence contributed to the present problem? |

| Past psychiatric history | Explore and try to understand patients’ beliefs about their mental illness and their perspective on treatment. What are patients’ typical reasons for hospitalization? Is there a history of nonadherence that leads to hospitalization? What was the context of their suicide attempts? |

| Past medical history | What is their understanding of their diagnosis and treatment? This may suggest how they are likely to approach their psychiatric illness. |

| Family history | If other family members have been mentally ill, what is the pattern of seeking or not seeking treatment? This can help identify family-held beliefs about mental illness and treatment. |

| Medications | How do patients feel about their medications? Do they feel the medications are necessary? Are they fearful of medication side effects and adverse events? What will they do if they experience a side effect or an adverse event? |

| Substance abuse | Is the patient actively using alcohol or illicit drugs? |

| Social history | Inquire about cultural, social, religious, or family-held beliefs that will affect the treatment. What is the patient’s living situation? Is the patient living in a safe environment with supports nearby? What kind of insurance and income does the patient have? How much can the patient afford, or is able to spend, per month on treatment? Ask what the patient feels about the clinician. Does the patient need “deputies” (family/friends) to partner in treatment protocols? |

| Mental status examination | Are there cognitive impairments (of attention or memory)? How is the patient’s insight and judgment? |

ONGOING ASSESSMENT

In general, questions should be asked in an empathic, nonthreatening way with a tone of genuine curiosity. For example, starting with open-ended questions (e.g., “How is it going with the medication?”) is more likely to be positively received than starting with closed-ended ones (e.g., “Do you take your medications as prescribed?”). After beginning with an open-ended question, asking specifically about which medications patients are taking and how they are taking them allows the clinician to assess patients’ understanding of the treatment recommendations. Ask, “Let me confirm that my records are accurate. What medications are you taking?” To specifically address adherence, disarming inquiries (e.g., “Sometimes it is difficult to remember to take medication. Have you ever noticed that you occasionally forget to take your pills?”) are less likely to be experienced as shaming or punitive. The goal is to foster a treatment relationship where patients feel comfortable truthfully reporting their behaviors.

THE DISCOVERY OF NONADHERENCE

During the course of treatment the majority of patients have issues with nonadherence. Effort should be invested in trying to determine the specific behavior patterns involved in medication nonadherence. This allows for the information to be incorporated into the individual’s treatment plan. Table 4-3 outlines examples of nonadherence, what questions should be raised, and what interventions may help.

| Examples of Nonadherence | Questions to Raise | Possible Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Missing a single dose per week. | Should the dose be skipped or the next dose doubled? | Use pill boxes or medication reminders. |

| Taking a lower dose than recommended. |

Once discovered, the solution may be simple. Often an empathic discussion enables the patient to feel heard and allows a reestablishment of adherence. However, some patients will continue to have significant barriers to adherence and will be difficult to manage (see Table 4-4 for strategies to enhance adherence).

Table 4-4 Strategies to Enhance Adherence

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Education

Unfortunately, the majority of psychiatric residency training programs do not have formal curricula on treatment adherence. As of 2005, the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology did not maintain medication adherence training as a specific goal. This is unfortunate given what is known about nonadherence. Some authors have designed and suggested courses for senior residents that specifically address assessment and management of nonadherence. Suggested core components of the curriculum include defining adherence and noncompliance; the relationship between adherence and efficacy; the assessment of adherence; the importance of the therapeutic alliance; and the interventions to improve adherence.32

1 Nose M, Barbui C, Tansella M. How often do patients with psychosis fail to adhere to treatment programmes? A systematic review. Psychol Med. 2003;33(7):1149-1160.

2 McEvoy J, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, et al. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:600-610.

3 Krulee DA, Hales RE. Compliance with psychiatric referrals from a general hospital psychiatry outpatient clinic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;10(5):339-345.

4 Demyttenaere K. Risk factors and predictors of compliance in depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13(suppl 3):S69-S75.

5 Qurashi I, Kapur N, Appleby L. A prospective study of noncompliance with medication, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior in recently discharged psychiatric inpatients. Arch Suicide Res. 2006;10(1):61-67.

6 Akerblad AC, Benstsson F, von Knorring L, Ekselius L. Response, remission and relapse in relation to adherence in primary care treatment of depression: a 2-year outcome study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(2):117-124.

7 Malla A, Norman R, Schmitz N, et al. Predictors of rate and time to remission in first-episode psychosis: a two-year outcome study. Psychol Med. 2006;36(5):649-658.

8 Katon W, Cantrell CR, Sokol MC, et al. Impact of antidepressant drug adherence on comorbid medication use and resource utilization. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(21):2497-2503.

9 Ascher-Syanum H, Faries DE, Zhu B, et al. Medication adherence and long-term functional outcomes in the treatment of schizophrenia in usual care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(3):453-460.

10 National Institute of Mental Health: The impact of mental illness on society. Available at www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/burden.cfm.

11 Aikens JE, Nease DE, Nau DP, et al. Adherence to maintenance-phase antidepressant medication as a function of patient beliefs about medication. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(1):23-30.

12 Aikens JE, Kroenke K, Swindle RW, et al. Nine-month predictors and outcomes of SSRI antidepressant continuation in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27(4):229-236.

13 Byrne N, Regan C, Livingston G. Adherence to treatment in mood disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19(1):44-49.

14 Fleck DE, Keck PEJr, Corey KB, et al. Factors associated with medication adherence in African American and white patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(5):646-652.

15 Yen CF, Chen CS, Ko CH, et al. Relationships between insight and medication adherence in outpatients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: prospective study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(4):403-409.

16 Liu-Siefert H, Adams DH, Kinon BJ. Discontinuation of treatment of schizophrenic patients is driven by poor symptom response: a pooled post-hoc analysis of four atypical antipsychotic drugs. BMC Med. 2005;3:21.

17 Droulout T, Liraud F, Verdoux H. Relationships between insight and medication adherence in subjects with psychosis. Encephale. 2003;29(5):430-437.

18 Perkins DO, Johnson JL, Hamer RM, et al. Predictors of antipsychotic medication adherence in patients recovering from a first psychotic episode. Schizophr Res. 2006;83(1):53-63.

19 Kamali M, Kelly BD, Clarke M, et al. A prospective evaluation of adherence to medication in first episode schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2006;21(1):29-33.

20 Hudson TJ, Owen RR, Thrush CR, et al. A pilot study of barriers to medication adherence in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):211-216.

21 Rettenbacher MA. Compliance in schizophrenia: psychopathology, side effects, and patients’ attitudes toward the illness and medication. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(9):1211-1218.

22 Priebe S, Watts J, Chase M, Matanoy A. Processes of disengagement and engagement in assertive outreach patients: qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:438-443.

23 Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Leckband S, Jeste DV. Interventions to improve antipsychotic medication adherence: review of recent literature. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23(4):389-399.

24 Vergouwen AC, Bakker A, Katon WJ, et al. Improving adherence to antidepressants: a systematic review of interventions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(12):1415-1420.

25 Velligan D, Lam YW, Glahn DC, et al. Defining and assessing adherence to oral antipsychotics: a review of the literature. Schizophrenia Bull. 2006;32(4):724-742.

26 Patel NC, Crismon ML, Miller AL, Johnsrud MT. Drug adherence: effects of decreased visit frequency on adherence to clozapine therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25(9):1242-1247.

27 Parellada E, Andrezina R, Milanova V, et al. Patients in the early phases of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders effectively treated with risperidone long-acting injectable. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(suppl 5):5-14.

28 Laux G, Heeg B, van Hout BA, et al. Costs and effects of long-acting risperidone compared with oral atypical and conventional depot formulations in Germany. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(suppl 1):49-61.

29 Diaz E, Neuse E, Sullivan MC, et al. Adherence to conventional and atypical antipsychotics after hospital discharge. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):354-360.

30 Young SD, Oppenheimer DM. Different methods of presenting risk information and their influence on medication compliance intentions: results of three studies. Clin Ther. 2006;28(1):129-139.

31 Norell SE. Accuracy of patient interviews and estimates of conical staff in determining medication compliance. Soc Sci Med. 1981;15:57.

32 Weiden PJ, Rao N. Teaching medication compliance to psychiatric residents: placing an orphan topic into a training curriculum. Acad Psychiatry. 2005;29:203-210.