TOWARDS EVIDENCE-BASED HEALTH POLICY: THE IMPORTANCE OF RESEARCH

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) ‘Health for All’ initiatives at Geneva in 1977, and the Health Targets and Implementation (Health for All) Committee’s report to Australian health ministers in 1988, encouraged the importance of research in health policy. The WHO Health for All perspective clearly identifies healthy public policy as the framework within which are contained all other health initiatives. An intersectoral approach includes transport, housing, employment and education as well as health. More recently, the phrase ‘whole-of-government approach’ is applied. A former Minister for Community Services and Health in 1988 recognised that to improve health and to reorient health services towards illness prevention involved long-term structural change, which could only be achieved by ‘the establishment of expanded national statistics and public health research programs to provide data on which to base long-term policy decisions’ (Blewett 1988 p 110). Subsequent governments have emphasised evidence-based health policy. The growth of evidence-based health policy grew out of the move towards evidence-based medicine (EBM), and has largely focused on international and national burden of disease studies. Neither evidence-based health policy nor EBM has been implemented as successfully as their proponents might have hoped, although the momentum is gathering.

Research projects related to health rarely have policy as a specifically identified focus, but most research into health and healthcare has implications for policy development. Research that includes an epidemiological component and explores the patterns of health and ill health in a population is highly relevant for health policy. Much of this research is organised around priority areas in health, the National Health Priority Areas (NHPA), to improve the health status of Australians. The NHPA have been added to incrementally from their introduction in 1994 by the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, including federal, state and territory health ministers, and now (2007) comprise: cancer control; cardiovascular health; mental health; injury prevention and control; diabetes; asthma; chronic diseases; arthritis and musculoskeletal conditions; and communicable diseases. A number of priority age groups for health interventions have recently been outlined and these include mothers and babies, children, young people, and older people. Together, the first six of the NHPA accounted in 1996 for 70% of the total burden of disease and injury in Australia (Mathers et al. 1999). The NHPA initiative recognised that to reduce the burden of disease, health policy should focus on those areas that contributed significantly to death and disease (but see Baum [1995] for a critique of goals and targets in health promotion and policy). The burden of disease trends in mortality and morbidity can also be extrapolated into the future, thus allowing policy to be made in advance of the trends. As Murray and Lopez (1996 p 740) argued, ‘A major effort to foster an independent, evidence-based approach to public health policy formulation is the Global Burden of Disease Study’. This arose in 1992 from a collaboration between the World Bank and WHO. Murray and Lopez refer throughout to the need to collect and to provide evidence for policy makers about the health problems of populations: ‘Public health policy formulation desperately needs independent, objective information on the magnitude of health problems and their likely trends, based on standard units of measurement and comparable methods’ (1996 p 740).

Health is now not only about illness, but about keeping healthy. Health is perceived as stemming from an emphasis on a healthy lifestyle at any age. Regular exercise and healthy eating are seen as contributing to a reduction in the incidence of Type II diabetes, to maintaining bone density and to a lowering of high blood pressure and high cholesterol. Governments at state, territory and federal levels exhort us to health with slogans such as ‘use it or lose it’, or ‘go for your life’, and for protection from too much UV sunlight; ‘slip, slop, slap’. It is of course less expensive for governments in the long run if people can remain in their homes for as long as possible, and reduce the need for medical visits and hospital and other institutional care.

Importantly, evidence-based health policy focused on risk factors, which had not been associated with the concern for individual illness and treatment. Looking at whole populations could include such factors as socioeconomic status, thus leading to large health gains from public health interventions. Important too in evidence-based health policy is the Social health atlas of Australia (Glover et al. 1999) and its related atlases for each state and territory based mainly on Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) data. Its aims are ‘to illustrate [through maps] the socioeconomically disadvantaged population and to compare this with patterns of distribution of major causes of illness and death, use of health services and health risk factors’ (Glover et al. 1999 p 3).

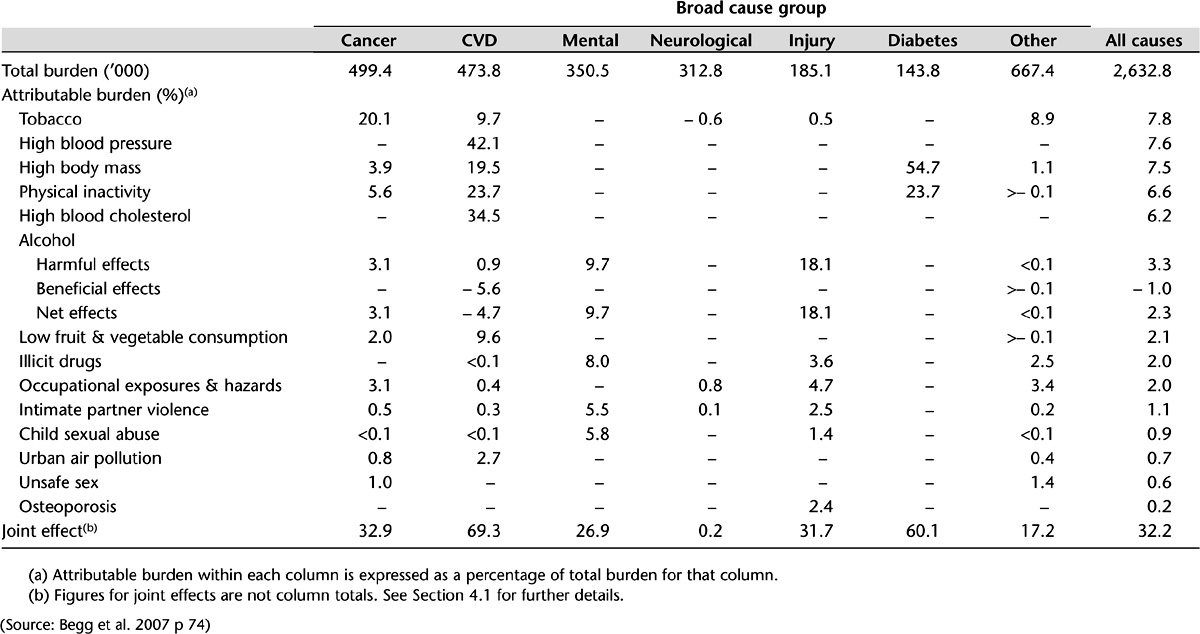

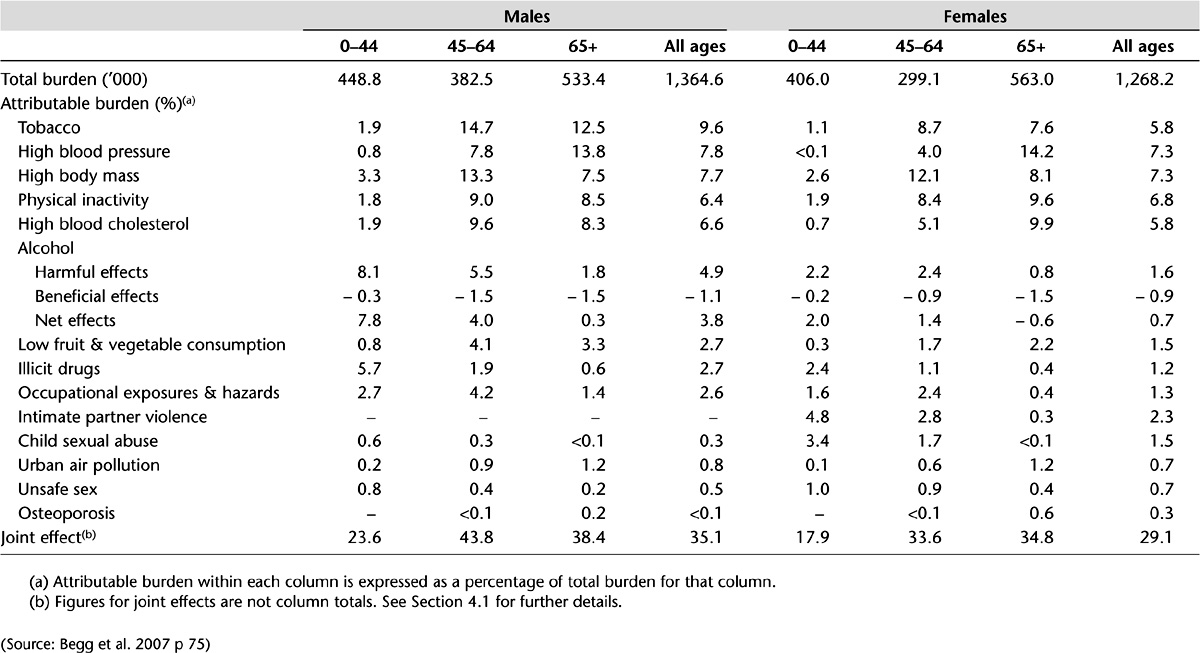

The 14 risk factors in the Australian burden of disease study (Begg et al. 2007) include physical inactivity, low fruit and vegetable consumption, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol and unsafe sex. Tobacco smoking was the risk factor responsible for the greatest burden of disease in Australia (see Tables 4.1 and 4.2 for selected determinants of health and their associated burden of disease). And as predicted by the Victorian Burden of disease study (Department of Human Services [DHS] 2001) on the basis of trends in mortality and morbidity, and in common with international and Australian studies, mental health disorders and diabetes will increase (Begg et al. 2007). In Chapter 5, the importance and application of Health Impact Assessment (HIA) in policy analysis is assessed.

Table 4.1 Individual and joint burden (DALYs) attributable to 14 selected risk factors by broad cause group, Australia, 2003

Table 4.2 Individual and joint burden (DALYs) attributable to 14 selected risk factors by sex and age group, Australia, 2003

COMMUNICABLE DISEASE

It could be argued that the kind of research funded has implications for subsequent policy development; for example, the stress on clinical research might lead to increased costs from the impetus given to technological development and pharmaceutical usage, whereas a focus on population health might reduce costs by emphasising the prevention of ill health. In the end, however, it is not researchers but policy planners, political decision makers, who choose to act upon the accumulated knowledge that might inform policy. The actual policy outcomes of a piece of research are often beyond the control of the researchers themselves, even if that research has been sought and funded by governments. Timing is also important. Because there are statistics about, say, an increase in a communicable disease, it does not mean that there will immediately be a policy response. The trend might need to be quite strong before there will be any action, and even then it will often come as a response to media or health professional pressure until the Minister for Health, or in some cases the Prime Minister, intervenes.

The Prime Minister promptly announced the introduction in 2007, after the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) had suggested a longer timeframe, of a free vaccination program for teenage girls and young women against the human papilloma virus (HPV) that can lead to cervical cancer. The TGA is the expert authority on efficacy and cost (Ch 17). The response was a community and political one. When the medical scientist who discovered the vaccine is made Australian of the Year for that discovery, it is difficult to deny its medical significance or its political importance. Not only that, but it is also about the health of young people and ultimately would be responsible for preventing death from cervical cancer. The decision had all the aspects of values, ethics, science and politics. Part of the political opposition to the decision was that it would increase sexual promiscuity; a moral rather than an evidentiary conclusion, and one that could hardly stand up to rational argument about how many lives could be saved. Although cost was not mentioned in the public announcements, this was obviously a consideration for the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) and indeed CSL, the manufacturer, did reduce the production price. In this case, the policy was based on research evidence, but it was a political decision in the end.

Infectious disease had been for many years considered to be part of the ‘old public health’ and largely eradicated by improvements in sanitation, hygiene, clean water and the use of antibiotics to give way to the ‘new public health’, which was more concerned with the so-called diseases of lifestyle. But in the 21st century, the world is facing problems from infectious diseases, from AIDS to influenza, comparable only to the great plague, and the influenza pandemic of 1919. Australia’s response to the threat of an avian influenza pandemic has been to lead the world in developing a vaccine. At first it was believed that we could not supply everyone but only emergency workers, health professionals and perhaps those most at risk if the H5N1 bird flu virus mutated and become capable of being transmitted between humans. In early 2007, however, the TGA gave regulatory approval to a vaccine that had passed its safety and efficiency measures and which protects against H5N1. CSL said that it could produce the vaccine quickly and in large quantities (Catalano 2007 p 6).

There are also less dramatic but still serious trends in infectious disease. A concerning increase in the rate of chlamydial infection is the result of a steady trend upwards and, while receiving some small amount of publicity in the media, it needs substantial pressure from the health professions before opportunistic tests on young women are carried out at the same time as the Pap smear test. The population rate (male and female) of the diagnosis of chlamydia more than doubled between 2000 and 2004: from 91.4 per 100,000 in 2000 to 186.1 per 100,000 in 2004 (AIHW 2006a). Notifications had been rising by 20% per year for the previous 5 years. Chlamydia is largely unnoticed in young women until the infection, in some women, causes such damage to the reproductive system that infertility is found, too late. Much money in the IVF program, not to mention distress, could be saved should a simple test be carried out in GPs’ surgeries. Currently, there are limited pilot studies being conducted to see the best way for testing young men and women for chlamydia infection before a national screening program can even begin. It is cost and competing priorities that can decide health priorities, although communicable diseases have been added to the national health priority areas (see above). The $12.5million allocated for the pilot studies was part of the first National Sexually Transmissible Infections Strategy for 2005–2008. Values are also important; sexual health is not something people like to talk about.

DATA FOR HEALTH

In some respects health research and funding mirror the federal system in Australia, which in turn is reflected in the organisation of the healthcare system in general; it is fragmented between the states, territories and the Commonwealth and there are gaps and duplication. There have, however, been huge inroads into the comprehensive collection of health and welfare data, largely due to the work of the AIHW since 1987. Indeed, the AIHW’s mission statement is the ‘Better health and wellbeing for Australians through better health and welfare statistics and information’. Working in partnership with the states and territories and with many research organisations, universities and health departments and the ABS, comprehensive data on health, housing and the community are now collected and disseminated (see also Ch 11). Evidence for the importance of research data can be gauged by the increased number of annual publications from the AIHW, from its conferences, and from its online usage and initiatives, such as its METeOR metadata management tool. The range of health areas researched can be gauged from its publications from Developing a nationally consistent data set for needle and syringe programs (AIHW 2007a) to the regularly released Health expenditure bulletin (AIHW 2006b), and the National public health expenditure report 2004–05 (AIHW 2007b). Similarly, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) advises the government on health and health research but, as Swerissen (1998 p 205) argues, although rational from a scientific point of view, in the ‘relatively packed gallery’ of interest groups, medical researchers and scientists are only a small part and, like the other groups, not always disinterested.

The medical profession, largely through the international Cochrane Collaboration, which reviews medical research articles and subjects them to meta analyses, relies for excellence (the gold standard) on randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and is enlarging the amount of its work which is evidence based (evidence-based medicine or EBM). Chapter 19 provides a useful account of EBM guidelines for prostate cancer. The Australian government funds the Cochrane Centre through the NHMRC. Still, only approximately 20% of the work of medical professionals is evidence based. Other health professions, such as physiotherapy and occupational therapy, have also supported an evidence base to their interventions.

ACCOUNTABILITY AND COST EFFECTIVENESS

Just as health policies are now more likely to be based on research, there is an increased recognition of the importance of evaluation of health programs (Mooney & Scotton 1999), which is linked both to notions of accountability and to scarcity of resources, which in turn are linked. There is a danger, however, that research for health policy development could become even more limited if, in a situation of scarcity and continued pressure on resources, it becomes confined to evaluations of existing health programs. Health research units within state and territory health departments are themselves subject to limited funding but have carried out some important research, as in the burden of disease, population health studies, and on inequalities in health. For example, in Victoria the first burden of disease study was carried out in 1996 and revised in 2001 and provides important information on health status, not only for the state government but also for local government level planning (DHS 2001). The states and territories contribute enormously to the collection of health data provided to the AIHW and evaluate many specific state, territory and local government programs in health and related areas. See, for example, the Environments for Health evaluation project in Victoria in Butterworth’s chapter (Ch 8); see also Chapter 21 for a discussion of environmental health programs and risk factors in, for example, the supply of our food.

Australia has had a relatively rational approach to healthcare decision making, which now involves a cost component as well as a safety and effectiveness component. Prescribed pharmaceuticals are approved for the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) by the PBAC after being examined by the TGA. Health services provided by GPs and public hospitals since 1984 come under Medicare and the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS), and medical services are, from 1997, subject to the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC). Incrementalism is evident in the regular changes to the groups of services already listed on the MBS to reflect the availability of new technologies or changes in medical practice or the addition of a new item. However, before a new procedure or technology can be listed on the MBS, its safety, effectiveness and cost effectiveness has to be assessed by the MSAC. MSAC assesses the evidence base of medical technologies. The aim is to ensure that the community has access to the best possible quality healthcare services at an affordable cost (Department of Health and Aged Care [DH&AC] 1999). Again, in common with the NHPA, if the Australian government is going to spend money, it has to be in an area that is going to be effective based on evidence or in the public service vernacular ‘more bang for your buck’. It is worth quoting the then Department of Health and Aged Care (DH&AC) in full about the context for this emphasis on cost and outcome effectiveness:

Meeting this aim has become increasingly important because of the pressures on healthcare expenditure, which has been steadily increasing … In 1996–97, expenditure on medical services via the MBS was around $A6.2 billion. Factors contributing to increases in healthcare include population growth, demographic changes, developments in new medical technologies, increasing fees and costs of delivering healthcare services, growth in the medical workforce and greater community expectations.

But even with increased expenditure, the expected improvements in health had not occurred. One could argue that this is because the large part of the expenditure is of course on illness care rather than on health promotion and illness prevention. In 2000–01, spending on health in Australia exceeded $60 billion for the first time, which was a rise of approximately 9 billion over the previous 2 years (AIHW 2002).

HEALTH EXPENDITURE

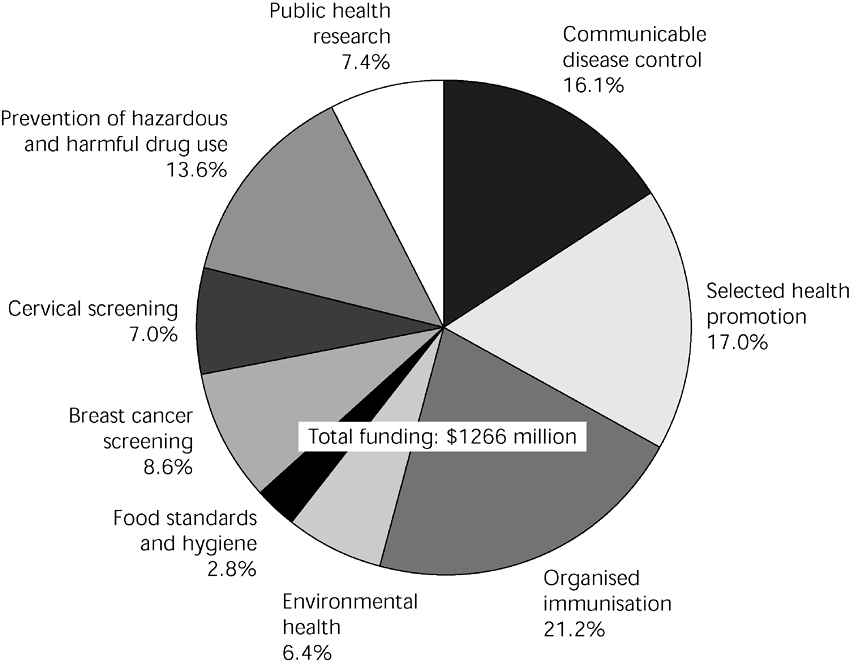

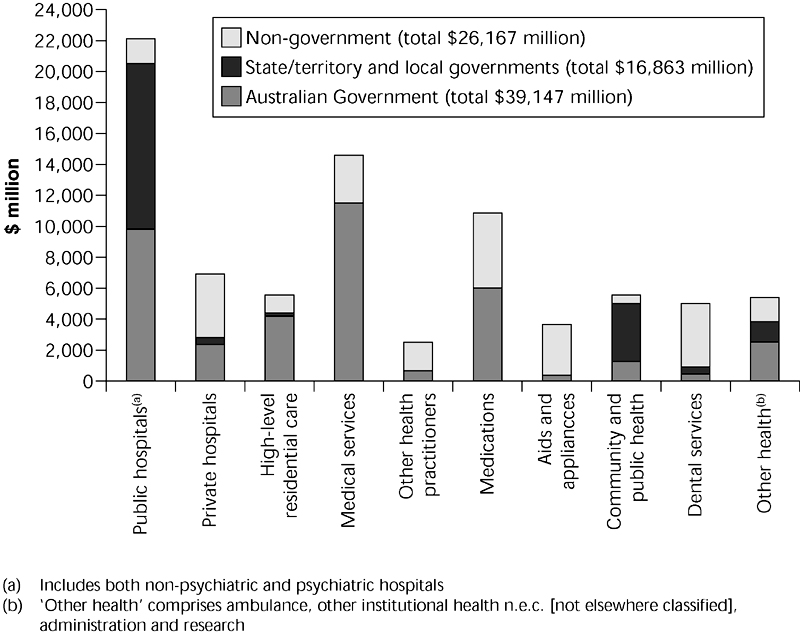

Total health expenditure was $78,598million in 2003–04, or 9.7% of GDP, which was up 0.1% from the previous year and up from 8.3% a decade earlier (AIHW 2006a). The overall result, as we have seen, has been to place more emphasis on public health and lifestyle changes, but this is still only marginal in terms of the costs of medical and hospital services. The public health share of recurrent health expenditure has remained relatively constant at 1.7% since 1999 (AIHW 2007b) and mainly reflects expenditure on immunisation. (See Figure 4.1 for government expenditure on public health activities.) Figure 4.2 shows government expenditure by the type of health service provided and the source of funds. Figure 4.2 is important because it shows that public hospitals, medical services, and pharmaceuticals together make up the largest funding outlays and that the Australian government is the major source of funds for medical services, health research and high-level residential care. The states and territories, and local government, however, are the major source of funds for community health services, and the states and territories and the Australian government share funding for public hospitals.

Figure 4.1 Government expenditure on public health activities 2003–04

Figure 4.2 Recurrent health expenditure, by health services area and source of funds, current price terms, 2004–05 Source: AIHW 2006b p 25

Agreements now called Australian Health Care Agreements (AHCAs), formerly Medicare Agreements, govern the funding of public hospitals and some other health services provided by the states and territories. The agreements run for 5 years and the current one is in effect from 1 July 2003 to 30 June 2008.

Of course, not all expenditure on healthcare is made by governments, non-government expenditure is mainly by individuals (20.3%) and by health insurance companies (7.1%). Together they spent in 2003–04, 32% of the total, including 4.6% designated as ‘other’ (AIHW 2006a p 301). In the same year, state, territory and local governments spent 22.6% and the Australian government 45.5% of total health expenditure.

ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER PEOPLE

The issue of research is itself a political issue. Aboriginal people suffer the poorest health of any group of Australians but can ‘claim that they are the most researched people in Australia but who … wonder just what good has emerged from all of that research effort’ (Mooney et al. 1999 p 264). Certainly, the division of responsibilities between state, territory and federal governments has not aided either Aboriginal health funding or the delivery of services.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, both men and women, die at younger ages than the rest of the population (see below). Average life expectancy for Indigenous men is 59.4 years and for Indigenous women is 64.8 (AIHW 2006a). Maternal and child health is approximately at the same stage as it was for the rest of Australia in the mid-20th century; for example, the infant mortality rate of 4.7 per 1000 live births in Australia in 2004 for the population as a whole is three times that for Indigenous people. It has improved but not at the same rate as for other Australians. Chapter 22 gives an in-depth portrayal of the difficulties of maintaining an infection-free environment for babies and children. It is the same for most other health statistics, whether it is asthma, kidney disease and dialysis, or mental health problems. For example, while the prevalence of diabetes is increasing in the population as a whole, nearly doubling, the rate of prevalence for diabetes was three times higher for Indigenous than for non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2006a). The rates of hospitalisation as a result of family violence is significantly higher for Indigenous people than for the rest of the population and this is higher in very remote areas, and for females rather than males at every age except for those up to 14 years and over 50 years. For Indigenous females it is highest for those aged 25–34 years at approximately 20 hospitalisations per 1000 women (AIHW et al. 2006).

The AIHW has compiled detailed statistics on Indigenous health and these are available in the biennial publication Australia’s health and in the joint ABS–AIHW publication, The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2005. It is important, however, to look not only at the health problems that Indigenous people in Australia undoubtedly experience, but also at the paucity of good housing and other environmental health benefits which contribute to good health, such as clean water, adequate sewerage systems and healthy nutrition. But there are important programs in which Indigenous people are engaged and from which they will ultimately benefit (see enHealth 2006). Aboriginal people themselves do not want the focus always to be on the negative indicators.

Contrary to popular belief, and in spite of the poor health experienced by Indigenous people, more money is not spent on Aboriginal health than on the rest of the population. In fact, it is lower. For the MBS and the PBS, average expenditure per Indigenous person was about one-third of that spent on other Australians per person. When spending on Indigenous health programs is combined with other Australian government expenditure on health services, ‘the overall Indigenous/non-Indigenous expenditure ratio … in 2001–02 was still just 0.86:1’ (AIHW 2006a p 292).

HOW DOES AUSTRALIA COMPARE?

When Australia is compared with other Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, its health expenditure to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratio meant that it was ranked eighth from the top (that is below those who had higher ratios) in 1998, and 13th from the top in 2003. This might suggest that although Australia’s health expenditure had increased during this period from 8.6% to 9.5% of GDP, it was being overtaken by countries who could less afford to spend more on health, such as Belgium, New Zealand and Poland (AIHW 2006a p 299). Not that increased expenditure is necessarily related to health as we have seen above, or to better services. The United States spent 15% of its GDP in 2003 (AIHW 2006a p 299), but is not regarded as having an enviable health system.

In terms of life expectancy, Australians are doing very well. Women especially can look forward to a long and relatively healthy lifespan of 83.3 years. Men are not very far behind with a life expectancy of 78.5 years (ABS 2006 reported in AMA 2007 p 8). Maternal and child health, except for that of Indigenous people, is also comparable to other countries with advanced economies. We share also a tendency to overweight and obesity (AIHW 2003) and to increasing rates of the diseases associated with overweight, lack of exercise, high cholesterol, processed rather than fresh foods, high salt intake and high blood pressure.

THE HEALTH WORKFORCE

When complementary therapists are added to the health workforce of nurses – health science professionals (includes physiotherapists, occupational therapists, orthoptists and so on), psychologists, pharmacists and medical practitioners – the total was approximately 570,000 in 2005, or 2802 per 100,000 population. This was an increase of 26% over the previous 5 years. These figures do not, however, provide any details of the over or under supply of health professionals in outer suburbs of cities or in rural and remote Australia (AIHW 2006a).

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the health workforce at the moment in terms of public policy is the Productivity Commission’s, Health Workforce Report (2006). Its recommendations on the medical task and role substitution by other health workers are described by the AMA as ‘the biggest threat to the medical profession’s morale and confidence since the medical indemnity crisis’ (AMA 2007 p 9). The Council of Australian Governments (COAG), which is the government body representing the states and the Australian government necessitated by a federal system, formerly called the Premiers’ Conference, has been working with various health interest groups on the Productivity Commission’s recommendations. Slightly more palatable, but not much more, to the AMA are recommendations on a single registration system for the main health professions. While recognising that a single registration system for medical professionals is sensible, to include other health professionals in the same system is anathema. It is a radical report in that it recommends opening up Medicare rebates to other professions, which would then allow some substitution of medical professionals. Medicare rebates have not changed substantially in terms of those who have access to them since the Hawke ALP government from 1983. The government appears to have already ruled out allied health workers gaining access to rebates because of the cost.

Nurses appear to be the biggest threat to medicine, but by no means the only group as new assistants in various areas are proposed. It is important too that not all medical practitioners agree with the AMA in being opposed to such developments. For example, there is such a shortage of general practitioners in urban as well as rural and remote areas that GPs support practice nurses extending their healthcare role. One such example is the right for practice nurses to receive Medicare rebates for carrying out Pap smear examinations in urban as well as in rural areas previously allowed. Similarly, the Australian government would allow practice nurses to carry out preventive health checks, such as blood pressure tests, while seeing patients for Pap smears (Australian Doctor 3 November 2006). Early responses by government to the report’s recommendations are that only those items that come under medical supervision attract the rebate, which is paid for nurses acting on behalf of and under the supervision of medical practitioners. Political parties, when in government, are naturally cautious about increasing expenditure by extending the numbers in the health workforce, but there are compelling arguments for some substitution of tasks if conducted by less well-paid staff members in a situation of scarcity of health personnel. Nevertheless, such changes are hard fought by the relevant interest groups. The health workforce is discussed in detail in Chapters 9 and 10.

An important component of the health, and more particularly the welfare, workforce, and one that has only relatively recently been costed and recognised, is the contribution of volunteers (AIHW 2005). It is a sector that is indeed increasing and is now expected to be included as a component of tender submissions to government (Tacticos & Gardner 2005). Similar to the discussion about substitution, health managers and personnel are concerned that the lines between volunteer and paid work are not always clear and that volunteers could replace some paid staff.

THE CORPORATISATION OF HEALTHCARE

The corporatisation, or ownership for profit by private companies, of health services appears to be occurring with little debate, except for some concern by the AMA, with the government allowing market forces to take their course. Pathology services are perhaps the first examples of amalgamations occurring on a large scale and then being bought out by large private health companies run for profit which often own private hospitals. Traditionally, pathology services had been owned either by individual pathologists or by a group of pathologists. General practice has also become subject to ownership by private companies. A perhaps worrying aspect of the corporatisation of health is vertical integration, where private hospitals, the suppliers of diagnostic tests such as pathology and radiology, pharmacies, and general practice are all linked. For the consumer, however, it is more convenient.

CONCLUSION

There has been an increased and increasing emphasis by governments on health rather than on illness, but this has yet to be supported by adequate funding or reflected in funding priorities. While illness and illness care still receive by far the largest component of the health budget, what is reflected in government priorities is a focus on the particular diseases that have attached to them a larger burden of illness and death, and thus are a larger cost to the community. Evidence-based health policy and EBM are the rational responses of governments attempting to achieve better health outcomes for the ever increasing amount of moneys spent in the health system. Australians are living longer, but Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander longevity and health still lags behind that of the rest of the population. The types of disease affecting the lives of Australians is also changing, with an increased threat of infectious disease, mental health problems and those arising from the consequences of obesity and an unhealthy lifestyle. The health workforce is also facing challenges from government in its attempts to break down the traditional organisation of healthcare. More details of these changes and the health of population groups can be found in Chapters 5, 9, 10, 14, 16, 18 and 22.