Procedure 4 Drainage of Purulent Flexor Tenosynovitis

Indications

Clinical diagnosis of acute suppurative tenosynovitis or an infection within the closed space of the fibrous flexor sheath requires early, aggressive treatment.

Clinical diagnosis of acute suppurative tenosynovitis or an infection within the closed space of the fibrous flexor sheath requires early, aggressive treatment.

Drainage is performed to prevent secondary sequelae of tendon sheath inflammation: stiffness, scarring, or tendon rupture.

Drainage is performed to prevent secondary sequelae of tendon sheath inflammation: stiffness, scarring, or tendon rupture.

Examination/Imaging

Clinical Examination

Purulent flexor tenosynovitis is a clinical diagnosis.

Purulent flexor tenosynovitis is a clinical diagnosis.

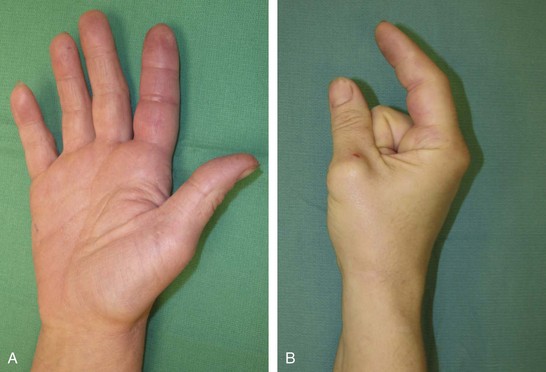

Kanavel signs (Fig. 4-1A and B) are as follows:

Kanavel signs (Fig. 4-1A and B) are as follows:

Evaluate for possible prior penetrating trauma to the palmar aspect of the digit, which may have seeded bacteria into the tendon sheath.

Evaluate for possible prior penetrating trauma to the palmar aspect of the digit, which may have seeded bacteria into the tendon sheath.

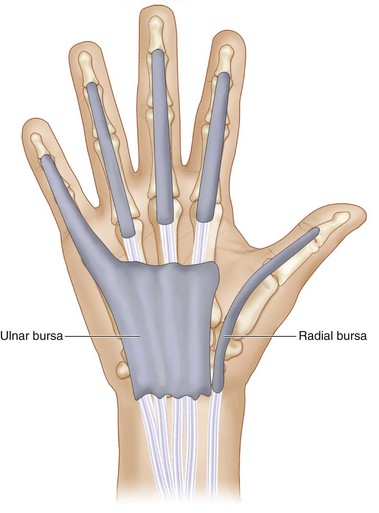

Tenosynovitis of the thumb and small finger may be less impressive owing to continuity of the fibrous flexor sheath with larger radial and ulnar bursa that allow spontaneous decompression (Fig. 4-2).

Tenosynovitis of the thumb and small finger may be less impressive owing to continuity of the fibrous flexor sheath with larger radial and ulnar bursa that allow spontaneous decompression (Fig. 4-2).

Infection of the thumb may spread to the small finger and vice versa.

Infection of the thumb may spread to the small finger and vice versa.

Examine for signs of gout or other intra-articular processes, which are treated medically.

Examine for signs of gout or other intra-articular processes, which are treated medically.

Examine for symptoms not confined to one joint. (Gout is typically monoarticular.)

Examine for symptoms not confined to one joint. (Gout is typically monoarticular.)

Without a prior penetrating wound, consider disseminated gonococcal infection or hematogenous spread of bacteria from other sources.

Without a prior penetrating wound, consider disseminated gonococcal infection or hematogenous spread of bacteria from other sources.

Surgical Anatomy

The fibrous flexor sheath (flexor zone 2) is an enclosed space extending from the metacarpal neck to just proximal to the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint (see Fig. 4-2).

The fibrous flexor sheath (flexor zone 2) is an enclosed space extending from the metacarpal neck to just proximal to the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint (see Fig. 4-2).

The small finger flexor sheath is in continuity with the ulnar bursa, extending to the proximal transverse carpal ligament.

The small finger flexor sheath is in continuity with the ulnar bursa, extending to the proximal transverse carpal ligament.

The thumb flexor sheath is in continuity with the radial bursa, extending to the proximal aspect of the transverse carpal ligament.

The thumb flexor sheath is in continuity with the radial bursa, extending to the proximal aspect of the transverse carpal ligament.

Radial and ulnar bursae may communicate to form a horseshoe abscess via the space of Parona in the volar forearm, between the pronator quadratus and the flexor digitorum profundus.

Radial and ulnar bursae may communicate to form a horseshoe abscess via the space of Parona in the volar forearm, between the pronator quadratus and the flexor digitorum profundus.

The anatomy of the annular pulley system is critical to identifying proximal and distal exposures at A1 and A4, respectively.

The anatomy of the annular pulley system is critical to identifying proximal and distal exposures at A1 and A4, respectively.

Exposures

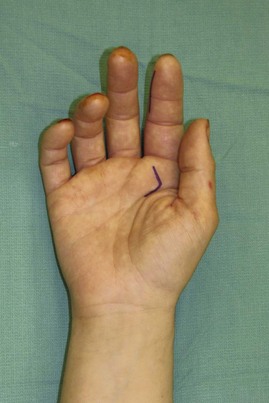

Distal exposure is though a longitudinal midaxial incision dorsal to the Cleland ligament, just proximal to the DIP joint on the side opposite the pinch surface, except for the small finger, where the incision is placed radially to avoid the resting ulnar side of the small finger (Fig. 4-3).

Distal exposure is though a longitudinal midaxial incision dorsal to the Cleland ligament, just proximal to the DIP joint on the side opposite the pinch surface, except for the small finger, where the incision is placed radially to avoid the resting ulnar side of the small finger (Fig. 4-3).

Proximal exposure is via a longitudinal chevron incision at the distal palmar crease just proximal to the A1 pulley.

Proximal exposure is via a longitudinal chevron incision at the distal palmar crease just proximal to the A1 pulley.

In the thumb, a thenar crease incision is used to gain access to the flexor pollicis longus under the distal transverse carpal ligament.

In the thumb, a thenar crease incision is used to gain access to the flexor pollicis longus under the distal transverse carpal ligament.

Pearls

Plan all incisions so that they may be extended distally or proximally as necessary.

Wide exposure of the entire fibrous flexor sheath is reserved for failure of limited exposure. The need for wide exposure is rare and can be associated with exposure of the tendon sheath and neurovascular structures, which leads to desiccation. Most early infections can be treated effectively with antibiotics, hand splinting in intrinsic plus position, and elevation. If the infection does not improve—based on the extent of the erythema and decreased pain—surgical drainage is necessary by the irrigation technique described in this chapter.

Extending the palmar incision proximally may be necessary if the infection has breached the fibrous flexor sheath.

In rare circumstances with ascending infection, a carpal tunnel exposure or volar forearm exposure may be necessary.

Procedure

Step 1: Distal Exposure of the Fibrous Flexor Sheath

Any contaminated puncture wounds should be thoroughly débrided and irrigated.

Any contaminated puncture wounds should be thoroughly débrided and irrigated.

A 1-cm midaxial longitudinal incision is made dorsal to the Cleland ligament on the noncontact surface of the finger overlying the A5 pulley (see Fig. 4-3).

A 1-cm midaxial longitudinal incision is made dorsal to the Cleland ligament on the noncontact surface of the finger overlying the A5 pulley (see Fig. 4-3).

The soft tissues of the finger, including the neurovascular bundles, are elevated in the volar flap of the soft tissue as the incision is carried bluntly down to the lateral aspect of the fibrous flexor sheath at a point overlying the A5 pulley.

The soft tissues of the finger, including the neurovascular bundles, are elevated in the volar flap of the soft tissue as the incision is carried bluntly down to the lateral aspect of the fibrous flexor sheath at a point overlying the A5 pulley.

The sheath is entered by sharply dividing the A5 pulley longitudinally over a distance of 5 mm.

The sheath is entered by sharply dividing the A5 pulley longitudinally over a distance of 5 mm.

Upon entering the fibrous flexor sheath, purulent material may be encountered; this material should be sent for culture and sensitivity.

Upon entering the fibrous flexor sheath, purulent material may be encountered; this material should be sent for culture and sensitivity.

Step 1 Pearls

In tenosynovitis, in which an atypical infection is expected, it is important to send the appropriate specimens: Gram stain, culture, sensitivity, acid-fast bacillus stain and culture, nontuberculous mycobacteria culture, fungus stain, and mycotic culture.

If a puncture wound is identified, it is advisable to include this wound in the exposure.

Step 2: Proximal Exposure of Fibrous Flexor Sheath

A longitudinal chevron incision is made over the A1 pulley, corresponding to the proximal aspect of the fibrous flexor sheath (Fig. 4-4).

A longitudinal chevron incision is made over the A1 pulley, corresponding to the proximal aspect of the fibrous flexor sheath (Fig. 4-4).

Volar soft tissue of the palm can be bluntly dissected and reflected radially and ulnarly to expose the A1 pulley with minimal risk to the neurovascular bundle.

Volar soft tissue of the palm can be bluntly dissected and reflected radially and ulnarly to expose the A1 pulley with minimal risk to the neurovascular bundle.

The A1 pulley does not need to be divided to place the irrigation catheter.

The A1 pulley does not need to be divided to place the irrigation catheter.

Step 3: Closed Tendon Sheath Irrigation

A 16-gauge intravenous catheter is introduced proximally into the fibrous flexor sheath under the A1 pulley (see Fig. 4-4).

A 16-gauge intravenous catheter is introduced proximally into the fibrous flexor sheath under the A1 pulley (see Fig. 4-4).

To prevent high-pressure irrigation, a wick or a second irrigation catheter is introduced through the distal incision directed proximally to allow irrigant egress. If the fluid flows easily through the sheath and runs off smoothly over the distal incision, however, a wick is not necessary.

To prevent high-pressure irrigation, a wick or a second irrigation catheter is introduced through the distal incision directed proximally to allow irrigant egress. If the fluid flows easily through the sheath and runs off smoothly over the distal incision, however, a wick is not necessary.

The tendon sheath should be irrigated with antibiotic-containing saline under gentle pressure until the effluent is clear, typically 500 mL total.

The tendon sheath should be irrigated with antibiotic-containing saline under gentle pressure until the effluent is clear, typically 500 mL total.

Drainage wicks should be placed in the proximal and distal incisions, which are left open.

Drainage wicks should be placed in the proximal and distal incisions, which are left open.

Continuous irrigation is not used.

Continuous irrigation is not used.

The tourniquet is released, hemostasis is achieved, and the incisions are closed loosely.

The tourniquet is released, hemostasis is achieved, and the incisions are closed loosely.

Step 3 Pearls

An irrigation catheter may be secured in place for continuous or periodic irrigation after the operation, if there is concern about more contamination in the tendon sheath. The need for irrigation of the tendon sheath on the ward is infrequent. It is preferable to irrigate gently through the catheter every 8 hours for 24 hours.

Step 3 Pitfalls

High-pressure irrigation may spread the infection.

One must be careful not to flush the irrigant into the subcutaneous tissue because this will cause marked swelling in the finger, resulting in finger compartment syndrome.

The fluid should flow readily through the tendon sheath until clear effluent is seen in the distal incision.

Postoperative Care and Expected Outcomes

The arm and fingers should be immobilized in a bulky splint and elevated.

The arm and fingers should be immobilized in a bulky splint and elevated.

If symptoms at presentation do not rapidly improve within 24 to 48 hours, the patient should return to the operating room for additional débridement, irrigation, or wider exposure of infection.

If symptoms at presentation do not rapidly improve within 24 to 48 hours, the patient should return to the operating room for additional débridement, irrigation, or wider exposure of infection.

Intravenous antibiotics for common pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, should be used initially and tailored appropriately.

Intravenous antibiotics for common pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, should be used initially and tailored appropriately.

Adequate analgesia is necessary to begin early motion.

Adequate analgesia is necessary to begin early motion.

The incisions typically heal without specific treatment, but edema may persist for weeks.

The incisions typically heal without specific treatment, but edema may persist for weeks.

The patient should be informed that scarring along the tendon sheath from the infection might prevent full finger motion.

The patient should be informed that scarring along the tendon sheath from the infection might prevent full finger motion.

Ten to 20% of patients fail to recover full motion.

Ten to 20% of patients fail to recover full motion.

About 66% of motion is achieved by 6 weeks, improving to 80% by 30 months.

About 66% of motion is achieved by 6 weeks, improving to 80% by 30 months.

Abrams RA, Botte MJ. Hand infections: treatment recommendations for specific types. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1996;4:219-230.

Lille S, Hayakawa T, Neumeister MW, et al. Continuous postoperative catheter irrigation is not necessary for the treatment of suppurative flexor tenosynovitis. J Hand Surg [Br]. 2000;25:304-307.

Neviaser RJ. Closed tendon sheath irrigation for pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1978;3:462-466.

Pang HN, Teoh LC, Yam AKT, et al. Factors affecting the prognosis of pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2007;89:1742-1748.