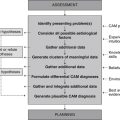

Case 4 Chronic venous insufficiency

Description of chronic venous insufficiency

Definition

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) is a pathological condition of the venous system, characterised by impaired venous blood flow in the lower limbs. The disorder presents as pathological changes to the skin, subcutaneous tissue and vascular tissue, and is a precursor to varicose veins and venous leg ulceration.

Epidemiology

CVI affects between 0.1 per cent and seventeen per cent of men, and from 0.2 per cent to twenty per cent of women.1 While evidence that links CVI occurrence to gender is inconsistent, being female is associated with an increased risk of CVI manifestations, including varicose veins1 and venous leg ulceration.2 CVI prevalence is also associated with increasing age, a relationship that may be attributed to the decline in blood vessel wall integrity and calf muscle strength over time.1

Aetiology and pathophysiology

A number of risk factors are connected with the development of CVI. Family history and increasing age, for instance, are both associated with an increased risk.1 In terms of modifiable risk factors, several studies have observed a higher prevalence and severity of CVI and varicose veins among people in occupations that typically require prolonged periods of standing, such as nurses, flight attendants and factory workers.1 The reduced calf-muscle pump activity associated with prolonged standing may contribute to the pathogenesis of CVI because of excessive lower limb venous congestion and pressure.

Another modifiable risk factor of CVI is macrovascular insult, the cause of which may be credited to lower limb trauma, surgery, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and/or pregnancy. The injury to the venous system triggers a cascade of events that contribute to CVI, including valvular incompetence, venous reflux (or retrograde blood flow), ambulatory venous hypertension, venous wall dilatation and elevated capillary filtration. Over time, these pathological changes lead to the formation of interstitial oedema, localised hypoxia, malnutrition and tissue destruction. Two mechanisms are believed to be responsible for the progression from a state of elevated capillary filtration pressure to changes in tissue perfusion and local architecture, including the extravasation or leakage of fibrinogen into the subcutaneous tisues and the subsequent formation of pericapillary cuffs, the intraluminal trapping of leucocytes and subsequent release of toxic metabolites, proteolytic enzymes and tissue necrosis factor-alpha. The extravasation of fibrinogen and leucocyte products into pericapillary tissue may also mediate inflammation, which suggests that CVI may be a disease of chronic inflammation.3

Clinical manifestations

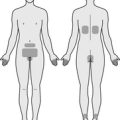

The early stages of CVI typically manifest as lower leg fatigue, heaviness, discomfort and pruritus. As the disease progresses, visible changes to the skin and subcutaneous tissue begin to emerge, such as lower leg oedema, ochre pigmentation, stasis dermatitis and lipodermatosclerosis. In the more advanced stages of CVI, a person may also present with superficial and deep varicose veins, as well as venous leg ulceration. The functional and cosmetic implications of these manifestations can significantly affect a person’s quality of life.4

Clinical case

44-year-old woman with mild chronic venous insufficiency

Rapport

Adopt the practitioner strategies and behaviours highlighted in Table 2.1 (chapter 2) to improve client trust, communication and rapport, as well as the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the clinical assessment.

Medical history

Lifestyle history

Illicit drug use

| Diet and fluid intake | |

| Breakfast | Coffee, porridge with skim milk. |

| Morning tea | Coffee, apple. |

| Lunch | Vegetable hotpot, sandwich with white bread, lettuce, tomato and carrot, chicken salad with tomato, cucumber, mixed greens and mushrooms. |

| Afternoon tea | Cheese and water crackers, apple juice, coffee. |

| Dinner | Beef and onion stew, chicken curry with white rice, grilled haddock with steamed carrot, cauliflower and broccoli. |

| Fluid intake | 2–3 cups of percolated coffee a day, 2–3 cups of water a day, 1 cup of juice a day. |

| Food frequency | |

| Fruit | 1–2 serves daily |

| Vegetables | 3–4 serves daily |

| Dairy | 2 serves daily |

| Cereals | 3–4 serves daily |

| Red meat | 3 serves a week |

| Chicken | 4 serves a week |

| Fish | 1 serve a week |

| Takeaway/fast food | <1 time a week |

Physical examination

Palpation

Popliteal, posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses are strong, regular and of equal amplitude bilaterally. No thrills are present over the neck, upper extremity, abdominal and lower extremity pulses or over the auscultatory areas of the heart. The point of maximum impulse (PMI) is located in the fifth intercostal space at the midclavicular line. The lower limbs and digits are warm. Mild pitting pedal oedema is present up to the ankle bilaterally, but is worse in the left foot. There is no palpable tenderness, numbness or fibrotic or sclerotic changes to the skin of the lower legs. Varicose veins over the bilateral popliteal fossae and calf are palpable.

Diagnostics

Pathology tests

Elevated levels of LDL-C, total cholesterol, triglycerides, homocysteine, apolipoprotein-B, asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) and/or C-reactive protein (CRP) may be indicative of cardiovascular disease.5 While these tests have little diagnostic value in CVI, they can be helpful in determining whether a person with lower limb vascular disease also has signs of systemic vascular disease.

Radiology tests

Doppler or ultrasound uses sound waves to assess blood flow velocity and direction, as well as blood flow disturbances of major blood vessels, including the veins of the lower limbs. This procedure is particularly useful for identifying the presence of chronic venous insufficiency (evidenced by retrograde venous blood flow), varicose veins and venous occlusion (evidenced by absent venous blood flow).5

Miscellaneous tests

The presence of arcus senilis, a whitish ring at the perimeter of the cornea, is highly suspicious of hypercholesterolaemia.6 Even though this sign has little diagnostic value in CVI, it may be useful in determining whether a person with lower limb vascular disease also has signs of systemic vascular disease.

Diagnosis

Clusters of data extracted from the health history, clinical examination and pertinent diagnostic test results point towards the following differential CAM diagnoses.

Planning

Goals

Expected outcomes

Based on the degree of improvement reported in clinical studies that have used CAM interventions for the management of CVI,7 the following are anticipated.

Application

Lifestyle

Physical exercise (Level III–1, Strength C, Direction o)

Physical exercise is likely to improve calf muscle pump function and lower limb venous haemodynamics and thus may be of benefit to people with venous insufficiency. While findings from a small RCT (n = 31 patients with CVI) demonstrated that a supervised calf muscle strength exercise program, together with wearing compression hosiery, was significantly more effective than control at improving mean venous ejection fraction at 6 months, the intervention was no more effective than control at improving venous reflux, venous severity scores and quality of life.8 Given that prolonged standing contributes to the pathogenesis of CVI, it is likely that a structured exercise program may still be useful in preventing the onset and/or progression of the disorder.

Nutritional supplementation

Ascorbic acid, beta-carotene, copper, glycine, hesperidin, leucine, lysine, quercetin, rutin, selenium and silicon

These nutrients play an important role in collagen synthesis. Many of them also exhibit actions pertinent to the management of CVI, including antienzymatic, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.9–11 Still, it is unclear whether monopreparations of these nutrients offer any clinical benefit to people with CVI, because of the paucity of clinical evidence in this area.

Herbal medicine

Aesculus hippocastanum (Level I, Strength A, Direction + (for mild to moderate CVI only))

Horsechestnut seed was traditionally used in Western herbal medicine to treat musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal and venous disorders, including haemorrhoids, varicose veins and leg ulceration. The majority of research to date, which has focused on the vascular effects of the plant, reveals that horsechestnut seed extract (HCSE) and the saponins and sapogenins of the plant inhibit hyaluronidase activity in vitro,12 scavenge superoxide-anions, increase fibroblast survival,13 inhibit histamine-induced vascular permeability in vivo and inhibit carageenin-induced paw oedema.14 These effects are fundamental to the management of venous insufficiency and may explain why a Cochrane review of 17 RCTs found orally administered HCSE (standardised to 50–150 mg aescin daily, for 20 days to 16 weeks) to be more effective than placebo and as effective as other phlebotonic agents at reducing leg pain, pruritus, oedema, leg volume, and ankle and calf girth in individuals with mild to moderate CVI.7 In severe or advanced CVI, HCSE appears to be less effective.15

Centella asiatica (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Gotu kola is used across several traditional systems of medicine as a treatment for skin complaints.16 Research to date suggests that the plant may also be suitable for the treatment of vascular disorders. Experimental data demonstrate that Centella asiatica flavonoids exhibit free radical scavenging activity in vivo.17 Clinically, titrated extracts of C. asiatica (60–180 mg daily) have been shown in three RCTs to be more effective than placebo at reducing ankle circumference and oedema at 4 weeks,18 lower leg volume at 6 weeks19 and leg heaviness and oedema at 8 weeks.20 While these effects are promising, further investigation is needed regarding the long-term safety and effectiveness of gotu kola in CVI.

Folia vitis viniferae (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Red vine leaf extract (RVLE) has been shown under experimental conditions to prevent venous endothelial damage from blood platelet and polymorphonuclear granulocyte release products, and to facilitate venular endothelial repair in vitro.21 These effects can be attributed to the flavonoids quercetin and isoquercitrin. The best available evidence from two RCTs supports these actions; it shows RVLE (360–720 mg daily) to be statistically significantly more effective than placebo at reducing calf circumference and CVI symptoms at 622 and 12 weeks.23 Changes in ankle girth were not consistent across the two studies, however.

Pinus maritima (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

French maritime pine bark extract, or pycnogenol, is not only a powerful scavenger of free radicals,24 but also an inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappaB and the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-1.25 These effects are fundamental in maintaining and improving venous wall integrity; they also appear to be of benefit in people with CVI. In fact, two RCTs involving a total of 80 patients with CVI found P. maritima extract (300 mg daily) to be significantly more effective than placebo at reducing leg heaviness and subcutaneous oedema at 8 weeks.26,27 Changes in venous haemodynamics were not consistent between studies.

Other herbs

Hamamelis virginiana (witch hazel) and Vaccinium myrtillus (bilberry) have been used traditionally and/or tested under experimental conditions for their anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and venotonic activity,31 but to date there is insufficient clinical evidence to support or refute the efficacy of these herbal monopreparations in humans with CVI.

Other

Reflexology (Level III-1, Strength C, Direction o)

Foot reflexology is based on a theory that stimulating specific zones of the feet, hands and/or ears can generate neurophysiological reflexes or responses in distant organs, glands and tissues. It is reasonable to hypothesise, therefore, that reflexology would be effective in CVI. To test this hypothesis, a single, blind RCT randomly allocated 55 healthy pregnant women with foot oedema to one of three groups: relaxation foot reflexology, lymphatic foot reflexology and rest.32 Each group received up to four 15-minute treatments. While all groups demonstrated a significant reduction in pain, discomfort and tiredness, there was no statistically significant difference between groups in mean ankle and foot girth measurements. It can be said, then, that the effectiveness of reflexology in venous insufficiency is inconclusive.

CAM prescription

Primary treatments

Secondary treatments

Referral

1. Beebe-Dimmer J.L., et al. The epidemiology of chronic venous insufficiency and varicose veins. Annals of Epidemiology. 2004;15:175-184.

2. Callam M., et al. Chronic ulcer of the leg: clinical history. British Medical Journal. 1987;294(6584):1389-1391.

3. Pappas P.J., et al. Causes of severe chronic venous insufficiency. Seminars in Vascular Surgery. 2005;18:30-35.

4. Duque M., et al. Itch, pain, and burning sensation are common symptoms in mild to moderate chronic venous insufficiency with an impact on quality of life. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2005;53(3):503-507.

5. Van Leeuwen A.M., Poelhuis-Leth D.J. Davis’s comprehensive handbook of laboratory and diagnostic tests with nursing implications, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: FA Davis Company; 2009.

6. Swartz M.H. Textbook of physical diagnosis: history and examination, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.

7. Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Horse chestnut seed extract for chronic venous insufficiency. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006. (1): CD003230

8. Padberg F.T., Johnston M.V., Sisto S.A. Structured exercise improves calf muscle pump function in chronic venous insufficiency: a randomized trial. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2004;39(1):79-87.

9. Higdon J. An evidence-based approach to vitamins and minerals. New York: Thieme; 2003.

10. Leach M.J. A critical review of natural therapies in wound management. Ostomy/Wound Management. 2004;50(2):36-51.

11. Shils M.E., et al. Modern nutrition in health and disease, 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

12. Facino R., et al. Anti-elastase and anti-hyaluronidase activities of saponins and sapogenins from Hedera helix, Aesculus hippocastanum, and Ruscus aculeatus: factors contributing to their efficacy in the treatment of venous insufficiency. Archiv der Pharmazie. 1995;328(10):720-724.

13. Masaki H., et al. Active-oxygen scavenging activity of plant extracts. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1995;18(1):162-166.

14. Peschen M., et al. Increased expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha and beta and vascular endothelial growth factor in the skin of patients with chronic venous insufficiency. Archives of Dermatological Research. 1998;290(6):291-297.

15. Leach M.J., Pincombe J., Foster G. Clinical efficacy of horsechestnut seed extract in the treatment of venous ulceration. Journal of Wound Care. 2006;15(4):159-167.

16. Bone K. A clinical guide to blending liquid herbs. St Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

17. Zheng C.J., Qin L.P. Chemical components of Centella asiatica and their bioactivities. Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine. 2007;5(3):348-351.

18. De Sanctis M.T., et al. Treatment of edema and increased capillary filtration in venous hypertension with total triterpenic fraction of Centella asiatica: a clinical, prospective, placebo-controlled, randomized, dose-ranging trial. Angiology. 2001;52(Suppl 2):S55-S59.

19. Cesarone M.R., et al. Microcirculatory effects of total triterpenic fraction of Centella asiatica in chronic venous hypertension: measurement by laser Doppler, TcPO2–CO2, and leg volumetry. Angiology. 2001;52(Suppl 2):S45-S48.

20. Pointel J.P., et al. Titrated extract of Centella asiatica (TECA) in the treatment of venous insufficiency of the lower limbs. Angiology. 1987;38(1 Pt 1):46-50.

21. Nees S., et al. Protective effects of flavonoids contained in the red vine leaf on venular endothelium against the attack of activated blood components in vitro. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 2003;53(5):330-341.

22. Kalus U., et al. Improvement of cutaneous microcirculation and oxygen supply in patients with chronic venous insufficiency by orally administered extract of red vine leaves AS 195: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Drugs in R&D. 2004;5(2):63-71.

23. Kiesewetter H., et al. Efficacy of orally administered extract of red vine leaf AS 195 (folia vitis viniferae) in chronic venous insufficiency (stages I–II). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 2000;50(2):109-117.

24. Busserolles J., et al. In vivo antioxidant activity of procyanidin-rich extracts from grape seed and pine (Pinus maritima) bark in rats. International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. 2006;76(1):22-27.

25. Cho K.J., et al. Effect of bioflavonoids extracted from the bark of Pinus maritima on proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 production in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2000;168(1):64-71.

26. Arcangeli P. Pycnogenol in chronic venous insufficiency. Fitoterapia. 2000;71(3):236-244.

27. Petrassi C., Mastromarino A., Spartera C. PYCNOGENOL in chronic venous insufficiency. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(5):383-388.

28. Kraft K., Hobbs C. Pocket guide to herbal medicine. New York: Thieme; 2004.

29. Bouskela E., Cyrino F.Z., Marcelon G. Possible mechanisms for the inhibitory effect of Ruscus extract on increased microvascular permeability induced by histamine in hamster cheek pouch. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1994;24(2):281-285.

30. Vanscheidt W., et al. Efficacy and safety of a Butcher’s broom preparation (Ruscus aculeatus L. extract) compared to placebo in patients suffering from chronic venous insufficiency. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 2002;52(4):243-250.

31. European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy (ESCOP). ESCOP monographs: the scientific foundation for herbal medicinal products, 2nd ed. Exeter: ESCOP; 2003.

32. Mollart L. Single-blind trial addressing the differential effects of two reflexology techniques versus rest, on ankle and foot oedema in late pregnancy. Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery. 2003;9(4):203-208.

33. Guillaume M., Padioleau F. Veinotonic effect, vascular protection, anti-inflammatory and free radical scavenging properties of Horse chestnut extract. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 1994;44(1):25-35.

34. Amsler F., Blattler W. Compression therapy for occupational leg symptoms and chronic venous disorders: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2008;35(3):366-372.