CHAPTER 4

Cervical Dystonia

Definition

Idiopathic cervical dystonia, the most common form of adult-onset focal dystonia, is twisting and turning of the neck caused by abnormal involuntary muscle contractures [1]. Cervical dystonia has also been known as spasmodic torticollis, which implies head jerking or neck spasms. However, these features are absent in 25% to 35% of patients with this condition [2]. Furthermore, the term spasmodic torticollis fails to emphasize the dystonic nature of the condition and the frequent association of cervical dystonia with dystonia in adjacent or remote body parts.

The incidence of cervical dystonia has been estimated at 1.07 per 100,000 person-years [3]. Women are affected 1.5 to 1.9 times more often than men are [2,4]. In 70% to 90% of cases, the disease begins between the fourth and sixth decades, with a peak incidence in the fifth decade of life [5].

The pathogenetic mechanisms are unclear, but increasing evidence suggests that cervical dystonia is influenced by genetic factors. Many patients with cervical dystonia have a family history [2]. Several gene loci, such as DYT1, DYT6, and DYT7, have recently been reported to be associated with cervical dystonia [6].

Cervical dystonia has also been reported to develop secondary to head, neck, and shoulder trauma [7]. The role of the sensory system is important in the pathogenesis of this condition (see section on symptoms) [8]. Impaired inhibition of sensory Ia afferent fibers, impairment of central sensory pathways, and increased spindle responsiveness secondary to overactive gamma spindle efferent fibers have been proposed as pathogenic mechanisms [9]. Other proposed mechanisms are vestibular impairment, dysfunction of the subcortical-cortical motor network, and dopaminergic dysfunction [9].

The natural course of dystonia has been reported [10], and in 68.1% of patients, dystonia remained focal. Progression of dystonia to sites other than the neck was noted in 31.9% of patients. The only risk factor for progression of dystonia to other body parts was longer duration of the disease. The rate of spontaneous remission was 20.8%. In most of the cases (87%), the remission occurred during the first 5 years after the onset of symptoms. The remission was sustained in 60% of the patients, and in 40% of the patients who had experienced remission, the disorder relapsed (nonsustained remission). The duration of the disease before remission was an important discriminating factor between sustained and nonsustained remission. The patients who experienced nonsustained remission had all done well within the first 2 years of the disorder; whereas in the patients who had sustained remission, the duration of dystonia before remission was more than 2 years.

Symptoms

Symptoms usually begin insidiously with complaints of a pulling or drawing in the neck or an involuntary twisting or jerking of the head. In most patients, the manifesting symptoms are sensory in nature (described variously as pain, pulling, or stiffness) or a degree of head rotation or deviation, with jerking and tremor of the head being distinctly less common complaints [2,4,11]. In 83% of patients, head deviation was constant rather than jerky (i.e., nonspasmodic) and demonstrated some degree of rotation (97%). Only a fraction of patients showed head jerks (35%) and neck spasms (37%), which are the cardinal features of “spasmodic” torticollis [2].

Several provocative and palliative factors are characteristic of idiopathic dystonia. Most notable is the use of a sensory trick or geste antagoniste. Gently touching the chin, back of the head, or top of the head relieves the symptoms. The use of sensory tricks to keep the head in the body midline position was reported by 88.9% of patients in one series [12]. The physiologic mechanism of sensory tricks remains unknown. Other effective maneuvers include leaning against a high-backed chair, placing something in the mouth, and pulling the hair. Early in the illness, these tricks are helpful in most patients, but they tend to lose effectiveness as the disease progresses. Less common palliative factors are relaxation, alcohol, and “morning benefit,” when symptoms are improved for a while after waking. Cervical dystonia is commonly exacerbated by activity (e.g., walking), fatigue, or stress [13].

Pain is a major source of disability in two thirds to three quarters of patients with cervical dystonia [2,3,14,15]. Pain severity was related to the intensity of dystonia and muscle spasms [2] but not to the duration of cervical dystonia and severity of motor dysfunction [14]. Pain was commonly described as tiring, radiating, tugging, aching, and exhausting [14].

Physical Examination

Inspection of the patient’s head posture is enough for the diagnosis of cervical dystonia. A wide variety of abnormal head and neck postures can occur (Fig. 4.1). Rotational torticollis is a rotation of the chin around the longitudinal axis toward the shoulder. Laterocollis is a rotation of the head in the coronal plane, moving the ear toward the shoulder. Anterocollis and retrocollis are rotations of the head in the sagittal plane; anterocollis brings the chin toward the chest, and retrocollis elevates the chin and brings the occiput toward the back. By convention, the direction of the rotation is defined by the chin, so right-turning torticollis means that the chin is turning to the right. There may also be sagittal or lateral deviation of the base of the neck from the midline [13]; 66% to 80% of patients present with a combination of these movements [2,4]. The most common component of complex deviations is rotational torticollis, followed by head tilt, retrocollis, and anterocollis. Isolated deviations (e.g., in a single plane) are seen in less than one third of patients. Notably, idiopathic cases of pure anterocollis are extremely uncommon. There is no statistically significant preponderance of right or left deviation [2,4,5,16]. The abnormal posture is present for more than 75% of the time in most patients, but findings may change in nature and directional preponderance over time [2].

Many patients have signs of dystonia involving other body segments at the time of presentation. Extracervical dystonia is found in 10% to 20% of patients [2,4]; the jaw (oromandibular), eyelids (blepharospasm), arm or hand (writer’s cramp), and trunk (axial) are the most frequently affected parts. A postural or kinetic hand tremor is found on physical examination in up to 25% of patients.

Although the term spasmodic torticollis implies head jerking or neck spasms, this feature is absent in 25.33% of patients. The adjectives spasmodic and spastic are misleading because there is no evidence that cervical dystonia is a spastic disorder or caused by dysfunction of the pyramidal tracts. Furthermore, the movements are not always spasmodic but may be sustained.

Although abnormal head position is enough for the diagnosis, physical examination in patients with cervical dystonia must be focused on detection of “pseudodystonia” secondary to structural abnormalities [17]. Normal findings in a complete neurologic examination are mandated to exclude secondary dystonia. The presence of corticospinal, sensory, cerebellar, oculomotor, or cortical signs with cervical or extracervical dystonia suggests secondary dystonia.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations due to cervical dystonia are found in almost all patients (99% of 220 patients) [16]. The severity of disability ranges from mild (subjective feeling of discomfort in social conditions without objective consequences on social life) to severe (qualitative and quantitative modification of the occupational level with resulting impairment of social life). One report documented depression in 24% of 67 patients with idiopathic cervical dystonia [18].

At some point during the illness, 75% of patients complain of pain, and patients usually consider the pain a major source of disability [2,4,10,15]. Pain is associated with constant head turning, greater severity of head turning, and presence of spasms [2]. Disability is also caused by task-specific limitations (e.g., inability to drive) and avoidance of social interaction due to abnormal posture. Questioning of patients about disability and clarification of the contributing factors are crucial for the optimal care of patients with idiopathic cervical dystonia [19].

Diagnostic Studies

Screening biochemical studies (blood chemistry screening test, complete blood count, thyroid function) in addition to a ceruloplasmin level should be performed to rule out other medical conditions that might cause dystonic features. Because various central nervous system lesions are known to be associated with cervical dystonia, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and cervical spine should be considered in all patients with a fixed painful neck posture [20]. If there is scoliosis, it may be evaluated with plain radiographs to document the baseline abnormality. In addition, Wilson disease should be excluded in all patients younger than 50 years by measurement of serum ceruloplasmin and a slit-lamp examination.

Treatment

Initial

The goals of treatment are to palliate, to improve the quality of life, and to prevent secondary complications. Reassurance is most important. Patients should be reassured that cervical dystonia is not dangerous and be reminded that cervical dystonia does not become generalized but may spread locally. However, they should also be told that treatment is symptomatic, not curative. Physicians must understand which aspects of the illness are most limiting because disability in cervical dystonia may be caused by many factors, such as pain, abnormal posture, functional limitation, social embarrassment, and depression. Detection of concomitant depression is crucial because it is a major source of disability, will limit therapeutic benefit, and is itself treatable. Secondary complications, such as radiculopathy, myelopathy, and dysphagia, must be recognized and treated. The evaluation of therapies for cervical dystonia is difficult: the abnormal postures, pain, and disability are not easy to quantitate; there are spontaneous remissions; and most studies are small and not randomized controlled trials [21]. Therefore, no universally accepted treatment protocol exists. However, the treatment of cervical dystonia has been revolutionized by chemodenervation with botulinum toxin. Medications are generally used as adjuncts to botulinum toxin. Adjunctive medications can prevent development of neutralizing antibodies because it is possible to lower dosages and frequency of botulinum toxin injections. Anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, and baclofen are the most widely used.

Other medications, such as dopamine-depleting agents (e.g., tetrabenazine) [22], are available, and many patients will require combination therapy. If therapy with botulinum toxin and oral medications fails, surgery may be required [9].

Rehabilitation

Patients with mild symptoms may be managed with physical measures or pharmacotherapy. Physical measures include the simple geste antagoniste (i.e., sensory tricks), biofeedback, mechanical braces, and physiotherapy. Use of the manipulative approach in the treatment of cervical dystonia is not appropriate under the assumption that the condition results from a spinal or orthopedic abnormality. In most patients, it is not possible to physically overcome the brain’s disordered central processing commands to displace the head position. Therefore physiotherapists and chiropractors are advised not to use orthopedic techniques or physical force as this may result in further discomfort or injury to the patient. However, it is beneficial to assist patients to use their own resources to improve head control by strengthening and enhanced flexibility.

Physical therapy is recommended as an adjunct to botulinum toxin injection. After treatment with botulinum toxin, there is less opposition from the dystonic musculature. The goal is to facilitate the patient’s increased control over head movement and posture once the antagonists are weakened. In a case report, reduction of the effective dose of botulinum toxin was also possible when physiotherapy management was added to a long-term treatment regimen [23].

Procedures

The prognosis of patients with cervical dystonia has been radically changed after the introduction of chemodenervation with botulinum toxin. Compared with all previous therapies, botulinum toxin benefits the highest percentage of patients in the shortest time, has been proved effective in many double-blind placebo-controlled and open trials [24], and has fewer side effects than other pharmacologic therapies [25]. For idiopathic cervical dystonia, serotype A is most widely used. The use of serotypes B and F is under investigation in patients who have become immunologically resistant to serotype A [26].

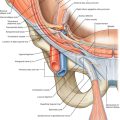

The identification of the sites of pain and the muscles responsible for the abnormal posture is the most important factor in botulinum toxin administration. The sternocleidomastoid, trapezius, splenius capitis, and levator scapulae are most commonly injected. An electromyographic study of 100 patients found that two or three muscles are most commonly abnormal [27]. In a recent study, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/ computed tomography was suggested to be a useful modality to identify dystonic cervical muscles [28]. The most commonly found abnormal muscles in each head posture are shown in Table 4.1. There is wide variability in the number of muscles injected, the number of injections per muscle, the concentration of botulinum toxin employed, and the use of electromyography-assisted injections, among other technical details. Which technique provides optimal results remains to be determined [29]. The average optimal dose for patients with cervical dystonia is varied between trials (mean Botox dose: 188 units [50 to 280 units]; mean Dysport dose: 577 units [250–1000 units]) [30]. It is important to customize the dosage and the muscles to suit the needs of the individual patients. The optimal dosing in a particular muscle has been assessed only for the sternocleidomastoid muscle by quantitative electromyography. Doses as small as 20 units of Botox reduced dystonic activity in the sternocleidomastoid muscle, whereas doses larger than 20 units offered minimal additional improvement [31]. Similarly, for Dysport, 100 units was sufficient to reduce the sternocleidomastoid muscle activity [31]; doses larger than 100 units were associated with a greater occurrence of dysphagia [32].

Table 4.1

Head Postures and the Muscles Most Commonly Responsible for the Posture

| Head Posture | Responsible Muscles |

| Rotational torticollis | Contralateral SCM Ipsilateral SC With or without contralateral SC |

| Laterocollis | Ipsilateral SCM, SC, TPZ |

| Retrocollis | Bilateral SC |

Modified from Deuschl G, Heinen F, Kleedorfer B, et al. Clinical and polymyographic investigation of spasmodic torticollis. J Neurol 1992;239:9-15.

SCM, sternocleidomastoid; SC, splenius capitis; TPZ, trapezius.

A benefit from botulinum toxin is generally seen within the first week but rarely may be delayed for up to 8 weeks. The benefit lasts an average of 12 weeks, and most physicians suggest that the injections be repeated every 3 to 4 months. The response to toxin is not affected by the pattern of deviation. Continued toxin injections provide progressive improvement of dystonia [29].

Patients with cervical dystonia who never benefit from botulinum toxin injection are considered primary nonresponders. This occurs in approximately 15% to 30% of patients [33]. In addition to the occurrence of primary treatment failure (patients never responding to injection), secondary failure may also occur in 10% to 15% of patients. These patients with initial improvement after treatment fail to respond to subsequent injections. Of the secondary failures, 35.7% were found to have antibodies to botulinum toxin by the mouse neutralization assay [33].

Surgery

Surgical therapy is recommended only for patients whose dystonia is prolonged, unresponsive to adequate trials of medication and botulinum toxin injections, and associated with significant pain or disability. Since the introduction of botulinum toxin, surgery is rarely required. Peripheral denervation procedures designed to denervate dystonic muscles selectively are the most widely practiced surgical procedures. Selective ramisectomy is a procedure that involves the selective section of dorsal rami of the upper cervical spinal nerves [34]. Selective denervation procedures are often combined with selective spinal accessory nerve section, anterior rhizotomy, or myotomy. Deep brain stimulation is becoming the standard of care for medically intractable, disabling dystonias. Advantages of deep brain stimulation include reversibility, adjustability, and continued access to the therapeutic target. Initial reports describing the use of deep brain stimulation in generalized dystonia have been encouraging, and experience in the use of deep brain stimulation to treat various forms of dystonia is continually growing [35].

Potential Disease Complications

Patients may develop cervical spondylosis with resulting radiculopathy or myelopathy [36]. Extracervical spread of dystonia is a progression of dystonia to a segmental pattern of dystonia. In one third of 72 patients who first had isolated cervical dystonia, the dystonia typically spread to the face, jaw, arms, or trunk [10].

Potential Treatment Complications

Side effects of botulinum toxin injections have been reported in 20% to 30% of patients per treatment cycle and approximately 50% of patients at some time during therapy. Dysphagia, neck weakness, and local pain at the injection site are the most commonly reported side effects, but dizziness, dry mouth, influenza-like syndrome, lethargy, dysphonia, and generalized weakness have been reported. The frequency of side effects varies widely, apparently on the basis of the dosage used [26].

Failure to spare ventral roots in selective ramisectomy injures the cervical and brachial plexuses and leads to the complications of diaphragmatic paralysis and dysphagia. Other sequelae of the selective denervation procedure include sensory loss in the distribution of the greater occipital nerve, paresthesias, and occasional sudden tic-like pain.