History: A 77-year-old man presents with dyspepsia.

1. Which of the following is the best diagnosis for the narrowing at the gastroesophageal junction?

C. Stricture, probably malignant

2. What kind of diaphragmatic hernia is most associated with gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD)?

3. Which of the following represent risk of GERD?

4. Which of the following statements about GERD is true?

A. There is almost a 2% prevalence of GERD in the population.

B. Most patients with untreated chronic severe GERD will go on to develop Barrett’s metaplasia.

C. A manifestation of chronic GERD is episodic insomnia.

D. The proximal esophagus is usually not spared in GERD.

ANSWERS

CASE 4

Reflux Esophagitis

1. B

2. B

3. C

4. C

References

Eisenberg RL. Esophageal ulceration. In: Gastrointestinal Radiology: A Pattern Approach. 4th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:43–51.

Cross-Reference

Gastrointestinal Imaging: THE REQUISITES, 3rd ed, p 16.

Comment

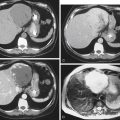

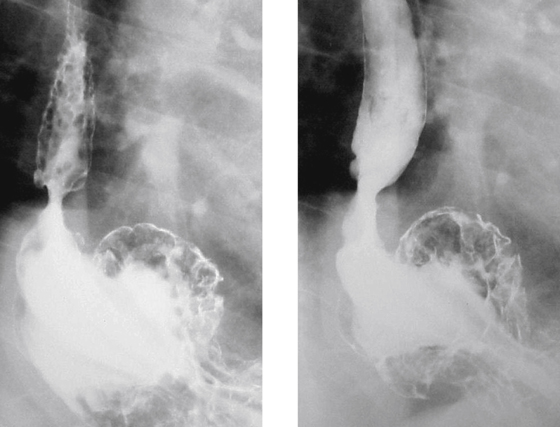

Radiologically, the findings of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are seen in the chronic phase. Radiographs are not yet able to identify the red mucosal coloring of early or acute disease. When seen in chronic disease, findings include fold thickening, granular appearance of the mucosa, superficial ulcerations, and developing luminal narrowing (see figures). Occasionally one encounters a “feline” esophagus in which fine transverse striations are seen transiently in the esophagus owing to brief contractions of the longitudinally orientated muscularis mucosae. This represents esophageal irritability in response to gastric acid on the mucosa. A similar finding characterized by fixed transverse folds, producing a “step-ladder” appearance, is believed to be due to scarring. This is similar to a finding in young patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. The presence of spontaneous gastroesophageal reflux and the way the esophagus handles it are most important. Is the gastric content cleared quickly from the esophagus by secondary wave activity? CT evaluation is less specific and might disclose some mild uniform thickening of the distal esophageal wall, a patulous esophagus, or fluid in the esophagus. The presence of a hiatal hernia, although not definitive, is associated with an increased incidence of reflux.

The complications of chronic GERD are Barrett’s metaplasia (a condition in which the esophageal squamous mucosa begins to take on a somewhat disordered appearance of gastric or intestinal mucosa). Barrett’s metaplasia is a precursor of adenocarcinoma in the distal esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. The other important complication is ulceration and strictures seen almost exclusively in the distal esophagus.

It is probably correct to assume that everyone, at some time or another, refluxes acid from the stomach up into the esophagus. However, the natural protective mechanisms—the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and the secondary esophageal clearing wave that strips the acid back into the stomach—are usually sufficient to protect us from damage. Why this protective mechanism fails in some patients is not fully understood at this time. However, the incidence of GERD is increasing. Some have attributed the rise to increasing obesity in the general population and others have questioned the untoward side effect of many of the newer hypertensive and cardiac medications of lowering the pressure of the LES.