CHAPTER 39

Ulnar Neuropathy (Wrist)

Definition

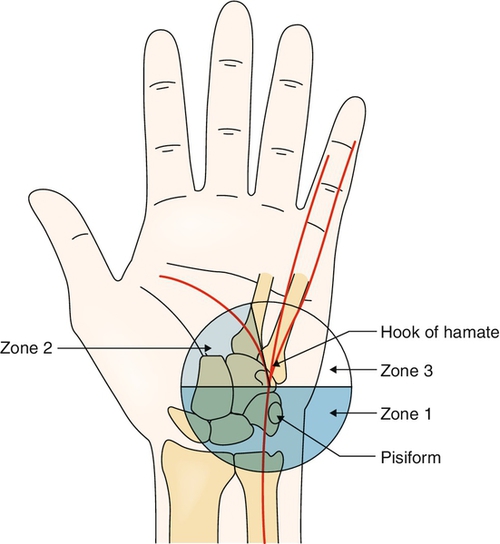

Entrapment neuropathy of the ulnar nerve can be encountered at the wrist in a canal formed by the pisiform and the hamate and its hook (the pisohamate hiatus). These are connected by an aponeurosis that forms the ceiling of Guyon canal (Fig. 39.1). This canal generally contains the ulnar nerve and the ulnar artery and vein. The following three types of lesions can be encountered [1].

Type II affects only the deep (motor) branch distally in Guyon canal and may spare the abductor digiti quinti, depending on the location of its branching. A further classification is type IIa (still pure motor), in which all the hypothenar muscles are spared because of a lesion distal to their neurologic branching.

Type III affects only the superficial branch of the ulnar nerve, which provides sensation to the volar aspect of the fourth and fifth fingers and the hypothenar eminence. There is sparing of all motor function, although the palmaris brevis is affected in some cases. This is the least common lesion encountered.

This injury is commonly seen in bicycle riders and people who use a cane improperly because they place excessive weight on the proximal hypothenar area at the canal of Guyon and therefore are predisposed to distal ulnar nerve traumatic injury, especially affecting the deep ulnar motor branch (type II) [2,3]. Entrapment at Guyon canal has also been associated with prolonged, repetitive occupational use of tools, such as pliers and screwdrivers [2]. With the advancement of endoscopic carpal tunnel release during the past few years, there have been reports of both adverse and favorable consequences to the ulnar nerve at Guyon canal, which is very close anatomically. There have been inadvertent injuries to the ulnar nerve as well as documented decompression and improvement of nerve conduction [4,5].

Other rare causes have been reported in the literature. These include fracture of the hook of the hamate, ganglion cyst formation, tortuous or thrombosed ulnar artery aneurysm (hypothenar hammer syndrome), osteoarthritis or osteochondromatosis of the pisotriquetral joint, anomalous variation of abductor digiti minimi, schwannomas, aberrant fibrous band, and idiopathic [6–9].

Of 250 wrists studied by 3 T magnetic resonance imaging assessment, it was noted that anatomy of the Guyon canal was normal in 168 (67.2%) wrists; 73 (29.2%) wrists presented with anatomic variations, and 9 (3.6%) wrists had derangements with clinical and radiologic features attributed to Guyon canal syndrome [10].

Symptoms

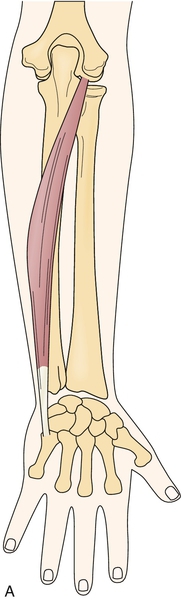

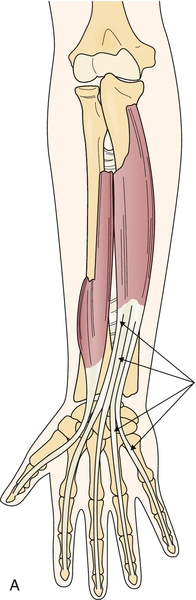

Signs and symptoms can vary greatly and depend on which part of the ulnar nerve and its terminal branches are affected and where along Guyon canal itself (Table 39.1). It is of great importance to be able to differentiate entrapment of the ulnar nerve at the wrist from entrapment at the elbow, which occurs far more commonly. The two clinical findings that confirm the diagnosis of Guyon canal entrapment instead of ulnar entrapment at the elbow are (1) sparing of the dorsal ulnar cutaneous sensory distribution in the hand and (2) sparing of function of the flexor carpi ulnaris and the two medial heads of the flexor digitorum profundus (Figs. 39.2 and 39.3). Otherwise, the symptoms in both conditions are generally similar and may include hand intrinsic muscle weakness and atrophy, numbness in the fourth and fifth fingers, hand pain, and sometimes severely decreased function.

Table 39.1

Volar Forearm and Hand: Ulnar Nerve

| Muscle | Action |

| Flexor carpi ulnaris | Flexes wrist, ulnarly deviates |

| Flexor digitorum profundus | Flexes distal interphalangeal joint (fourth and fifth) |

| Abductor digiti quinti* | Analogous to dorsal interosseous |

| Flexor digiti quinti*† | Analogous to dorsal interosseous |

| Opponens digiti quinti*† | Flexes and supinates fifth metacarpal |

| Volar interossei* | Adduct fingers, weak flexion metacarpophalangeal |

| Dorsal interossei*† | Abduct fingers, weak flexion metacarpophalangeal |

| Lumbricals (ring and fifth)*† | Coordinate movement of fingers; extend interphalangeal joints; flex metacarpophalangeal joints |

| Adductor pollicis* | Adducts thumb toward index finger |

| Lumbricals (ring, small)* | Coordinate movement of fingers; extend interphalangeal joints; flex metacarpophalangeal joints |

* Hand intrinsic muscles.

† Hypothenar mass.

Physical Examination

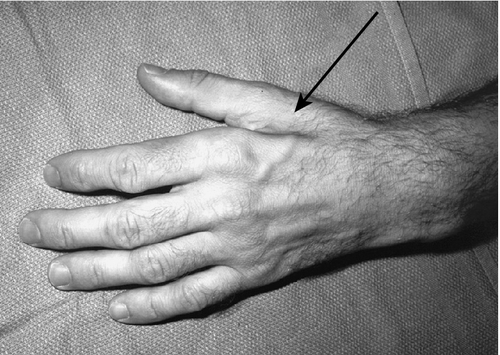

Careful examination of the hand and a thorough knowledge of the anatomy of motor and sensory distribution of ulnar nerve branches are required to determine the location of the lesion. Except for the five muscles innervated by the median nerve (abductor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, flexor pollicis brevis superficial head, and first two lumbricals), the ulnar nerve supplies every other intrinsic muscle in the hand. Classically, there is notable atrophy of the first web space due to denervation of the first dorsal interosseous muscle (Fig. 39.4). In lesions involving the motor branches where the compression is in the proximal aspect of Guyon canal, there will be weakness and eventually atrophy of the interossei, the adductor pollicis, the fourth and fifth lumbricals, and the deep head of the flexor pollicis brevis. The palmaris brevis, abductor digiti quinti, opponens digiti quinti, and flexor digiti quinti may be involved or spared, depending on the level of the lesion.

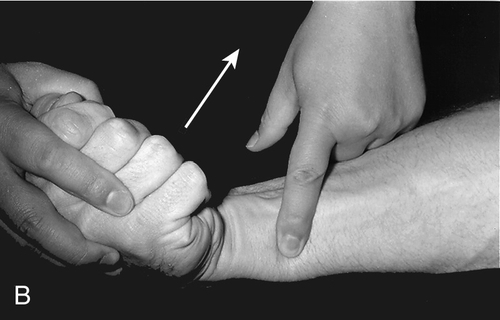

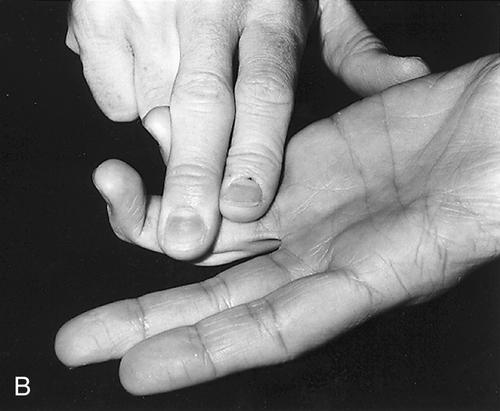

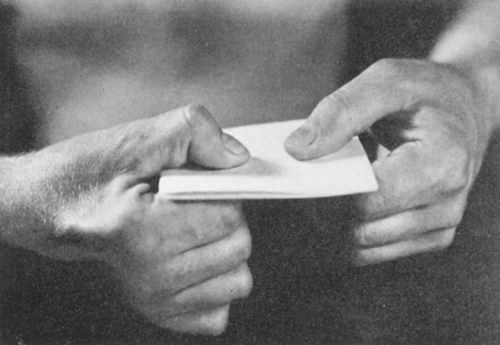

Sensory examination in all but type II, in which the compression of the ulnar nerve is at the level of the lower wrist, reveals decreased sensation of the volar aspect of the hypothenar eminence and the fourth and fifth fingers (with splitting of the fourth in most patients). There is always sparing of the sensation of the dorsum of the hand medially because it is innervated by the dorsal ulnar cutaneous branch of the ulnar nerve, which branches off the forearm proximal to Guyon canal [1]. The ulnar claw (hyperextension of the fourth and fifth metacarpophalangeal joints with flexion of the interphalangeal joints) seen in more proximal lesions may be more pronounced because of preserved function of the two medial heads of the flexor digitorum profundus. This creates flexion that is unopposed by the weakened interossei and lumbricals [1,11]. The flexor carpi ulnaris has normal strength. All the signs of intrinsic hand muscle weakness that are seen in more proximal ulnar nerve lesions, such as the Froment paper sign, are also found in Guyon canal entrapment affecting the motor nerve fibers (Fig. 39.5) [12]. Grip strength is invariably reduced in these patients when the motor branches of the ulnar nerve are affected [13].

Type III is the least common and involves pure sensory loss from the compression of the superficial branch at the distal aspect of Guyon canal.

Functional Limitations

Functional loss can vary from isolated decreased sensation in the affected region to severe weakness and pain with impaired hand movement and dexterity. As can be anticipated, lesions affecting motor nerve fibers are functionally more severe than those affecting only sensory nerve fibers. The patient may have trouble holding objects and performing many activities of daily living, such as occupation, daily household chores, grooming, and dressing. Vocationally, individuals may not be able to perform the basic requirements of their jobs (e.g., operating a computer or cash register, carpentry work). This can be functionally devastating.

Diagnostic Studies

The cause of the clinical lesion suspected after careful history and physical examination can be investigated with the use of imaging techniques. Plain radiographs could reveal a fracture of the hamate or other carpal bones as well as of the metacarpals and the distal radius, especially if there has been a traumatic injury. Magnetic resonance imaging [10] and computed tomography (multislice spiral computed tomographic angiography, multidetector computed tomography) can be helpful if a fracture, angioleiomyoma, tortuous ulnar artery, pseudoaneurysm of the ulnar artery, lipoma, or ganglion cyst is suspected [14–17]. As technology and accuracy of ultrasound equipment have advanced, there are now reports of the use of conventional and color duplex sonography to diagnose conditions such as thrombosed aneurysm of the ulnar artery [18,19].

Nerve conduction study and electromyography are helpful in confirming the diagnosis and the classification as well as in determining the severity of the lesion and the prognosis for functional recovery. Ulnar nerve entrapment in Guyon canal may be due to recurrent carpal tunnel syndrome [4]. As a rule, the dorsal ulnar cutaneous sensory nerve action potential is normal compared with the unaffected side [4]. Abnormalities in both sensory and motor conduction studies are seen in type I. The ulnar sensory nerve action potential recorded from the fifth finger is normal in type II, and an isolated abnormality is encountered in type III. The compound muscle action potential of the abductor digiti quinti is normal in types IIa and III. For this reason, it is important to perform motor studies recording from more distal muscles, such as the first dorsal interosseous [20]. Motor conduction studies should include stimulation across the elbow to rule out a lesion there, as it is far more common. Furthermore, ulnar nerve stimulation at the palm, after the traditional stimulation at the wrist and across the elbow, can be useful in sorting out the location of the compression and which fascicles are affected [21]. Care must be taken not to overstimulate because median nerve–innervated muscles are very close (i.e., lumbricals 1 and 2), and their volume-conducted compound muscle action potentials could confuse the diagnosis. A “neurographic” palmaris brevis sign has been described in type II ulnar neuropathy at the wrist [22]. This consists of a positive wave preceding the delayed abductor digiti minimi motor response, presumably caused by volume-conducted depolarization of a spared palmaris brevis muscle. Needle electromyography helps in documenting axonal loss, determining severity of the lesion to allow prognosis for recovery, and more precisely localizing a lesion for an accurate classification. The flexor carpi ulnaris and the ulnar heads of the flexor digitorum profundus should be completely spared in a lesion at Guyon canal [23].

Treatment

Initial

Initial treatment involves rest and avoidance of trauma (especially if occupational or repetitive causes are suspected). Ergonomic and postural adjustments can be effective in these cases. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in cases in which an inflammatory component is suspected can also be beneficial. Analgesics may help control pain. Low-dose tricyclic antidepressants may be used both for pain and to help with sleep. More recently, the use of antiepileptic medications for neuropathic pain syndromes has been increasing because of good efficacy. Prefabricated wrist splints may be beneficial and are often prescribed for night use. For individuals who continue their sport or work activities, padded, shock-absorbent gloves may be useful (e.g., for cyclists, jackhammer users).

Rehabilitation

A program of physical or occupational therapy performed by a skilled hand therapist can help obtain functional range of motion and strength of the interossei and lumbrical muscles. Instruction of the patient in a daily routine of home exercises should be done early in the diagnosis. Static splinting (often done as a custom orthosis) with an ulnar gutter will ensure rest of the affected area. In more severe cases, the use of static or dynamic orthotic devices may be considered to improve the patient’s functional level. Weakness in the ulnar claw deformity can be corrected to improve grasp with the use of a dorsal metacarpophalangeal block (lumbrical bar) to the fourth and fifth fingers with a soft strap over the palmar aspect [25].

A work site evaluation may be beneficial as well. Ergonomic adaptations can prove helpful to individuals with ulnar nerve entrapment at the wrist (e.g., switching to a foot computer mouse or voice-activated computer software).

Procedures

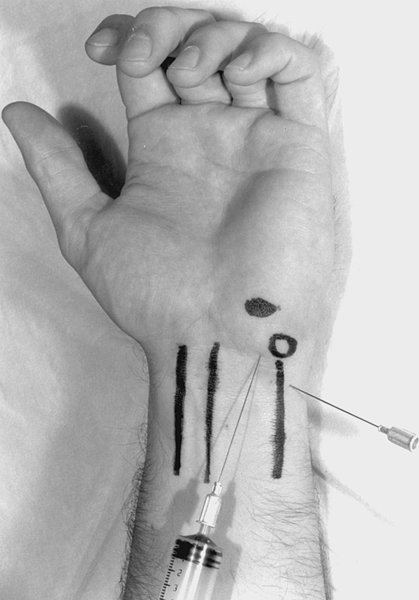

Injections into Guyon canal may be tried if a compressive entrapment neuropathy is suspected and generally provide symptomatic relief (Fig. 39.6) [2].

Under sterile conditions, with use of a 25-gauge, 11⁄2-inch disposable needle, a mixture of corticosteroid and 1% or 2% lidocaine totaling no more than 1 mL is injected into the distal wrist crease to the radial side of the pisiform bone; the needle is angled sharply distally so that its tip lies just ulnar to the palpable hook of the hamate [2,26]. Postinjection care includes ensuring hemostasis immediately after the procedure, local icing for 5 to 10 minutes, and instructions to the patient to rest the affected limb during the next 48 hours.

Surgery

Surgery is recommended when there is a fracture of the hook of the hamate or of the pisiform or a tortuous ulnar artery that causes neurologic compromise. Ganglion cyst and pisohamate arthritis are also indications for surgical treatment. Surgery in general involves exploration, excision of the hook of hamate or pisiform (if fractured), repair of the ulnar artery as necessary, decompression, and neurolysis of the ulnar nerve [2,6]. Experience and a sound knowledge of the possible anatomic variations (i.e., muscles, fibrous bands) and the arborization patterns of the ulnar artery in Guyon canal are of great importance in promoting a positive outcome when surgery is medically necessary [8,27].

Preoperatively, the patient is educated about the expected clinical course after nerve release. The patient is warned about incisional tenderness for 8 to 12 weeks postoperatively. Nighttime numbness, weakness, or clumsiness will resolve gradually, and recovery may be incomplete.

For days 0 to 5, the patient is instructed in isolated tendon glide exercises for all digits. No heavy resistance activities are permitted for 6 weeks after surgery. From 1 to 6 weeks, active range of motion of the wrist, edema control, scar massage, and desensitization are initiated when the incision is made accessible. From 6 to 12 weeks, progressive strengthening exercises are initiated [28].

Potential Disease Complications

The severity and type of lesion of the ulnar nerve at the wrist will ultimately determine the complications. Severe motor axon loss will cause profound weakness and atrophy of ulnar-innervated muscles in the hand and render the patient unable to perform even simple tasks because of lack of vital grip strength. Some patients also have chronic pain in the affected hand, which can be severely debilitating, perhaps inciting a complex regional pain syndrome, and it can predispose them to further problems, such as depression and drug dependency.

Potential Treatment Complications

The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be carefully monitored because there are potential side effects, including gastrointestinal distress and cardiac, renal, and hepatic disease. Low-dose tricyclic antidepressants are generally well tolerated but may cause fatigue, so they are usually prescribed for use in the evening. Injection complications include injury to a blood vessel or nerve, infection, and allergic reaction to the medication used. Complications after surgery include infection, wound dehiscence, recurrence, and, rarely, complex regional pain syndrome.