CHAPTER 37

Trigger Finger

Definition

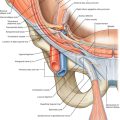

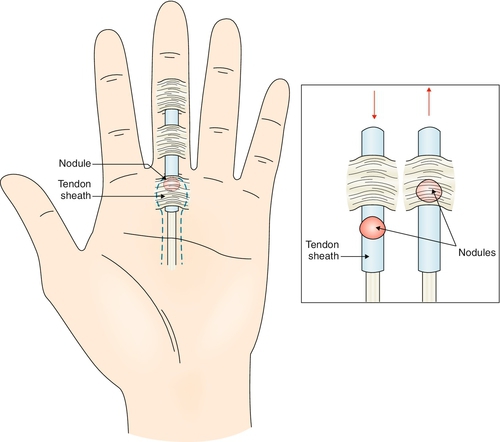

Trigger finger is the snapping, triggering, or locking of a finger as it is flexed and extended. This is due to hypertrophy and fibrocartilaginous metaplasia at the tendon-pulley interface that does not allow the tendon to glide normally back and forth under the pulley. Trigger finger is thought to arise from high pressures at the proximal edge of the A1 pulley when there is a discrepancy in the diameter of the flexor tendon and its sheath at the level of the metacarpal head [1] (Fig. 37.1). The thumb (33%) and the ring finger (27%) are most commonly affected in adults, but 90% of pediatric trigger fingers involve the thumbs, 25% of which are bilateral [1]. It is often encountered in patients with diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis [2,3]. The relationship of trigger finger to repetitive trauma has been cited frequently in the literature [3–5]; however, the exact mechanism of this correlation is still open to debate [6]. Rarely, it is due to acute trauma or space-occupying lesions [7–9].

Symptoms

Patients typically complain of pain in the proximal interphalangeal joint of the finger, rather than in the true anatomic location of the problem—at the metacarpophalangeal joint. Some individuals may report swelling or stiffness in the fingers, particularly in the morning. Patients may also have intermittent locking in flexion of the digit, which is overcome with forceful voluntary effort or passive assistance. Involvement of multiple fingers can be seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or diabetes [2,3]. In one study, the perioperative symptoms differed for trigger thumbs versus trigger fingers [10]. In this study, patients complained of pain with motion with trigger thumb; with trigger finger, they complained primarily of triggering and loss of range of motion.

Physical Examination

The essential element in the physical examination is the localization of the disorder at the level of the metacarpophalangeal joint. There is palpable tenderness and sometimes a tender nodule or crepitus over the volar aspect of the metacarpal head. Swelling of the finger may also be noted. Opening and closing of the hand actively produces a painful clicking as the inflamed tendon passes through a constricted sheath. With chronic triggering, the patient may have interphalangeal joint flexion contractures [11]. Therefore it is important to determine whether there is normal passive range of motion in the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints. Neurologic examination findings, including muscle strength, sensation, and reflexes, should be normal, with the exception of severe cases associated with disuse weakness or atrophy. Comorbidities can affect the neurologic examination findings as well (e.g., patients with diabetic neuropathy or carpal tunnel syndrome may have impaired sensation).

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations include difficulty with grasping and fine manipulation of objects due to pain, locking, or both. Fine motor problems may include difficulty with inserting a key into a lock, typing, or buttoning a shirt. Gross motor skills may include limitation in gripping a steering wheel or in grasping tools at home or at work.

Diagnostic Studies

This is a clinical diagnosis. Patients without a history of injury or inflammatory arthritis do not need routine radiographs [12]. Magnetic resonance imaging can confirm tenosynovitis of the flexor sheath, but this offers minimal advantage over clinical diagnosis [13]. Alternatively, a diagnostic ultrasound examination can show tendon nodules, tenosynovitis, and active triggering at the level of the A1 pulley.

Treatment

Initial

The goal of treatment is to restore the normal gliding of the tendon through the pulley system. This can often be achieved with conservative treatment. Typically, the first line of treatment is a local steroid injection [14]. The determination of whether to inject first or to try noninvasive measures is often based on the severity of the patient’s symptoms (more severe symptoms generally respond better to injections), the level of activity of the patient (e.g., someone who needs to return to work as quickly as possible), and the patient’s and clinician’s preferences.

Noninvasive measures generally involve splinting of the metacarpophalangeal joint at 10 to 15 degrees of flexion with the proximal interphalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints free, for up to 6 weeks continuously [15]. This has been reported to be effective, although less so in the thumbs [16,17]. Also, splinting provides a reliable and functional means of treating work-related trigger finger without loss of time from work [18]. Additional conservative treatment includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and avoidance of exacerbating activities, such as typing and repetitive gripping. Wearing padded gloves provides protection and may help decrease inflammation by avoiding direct trauma.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation may include treatment with an occupational or physical therapist experienced in the treatment of hand problems. Supervised therapy is generally not necessary but may be useful in the following scenarios: when a patient has lost significant strength, range of motion, or function from not using the hand or from prolonged splinting; when modalities such as ultrasound and iontophoresis are recommended to reduce inflammation; and when a customized splint is deemed to be necessary.

Therapy should focus on increasing function and decreasing inflammation and pain. This can be done by techniques such as ice massage, contrast baths, ultrasound, and iontophoresis with local steroid use. For someone with a very large or small hand or other anatomic variations (e.g., arthritic joints), a custom splint may fit better and allow him or her to function at work more easily than with a prefabricated splint. Range of motion and strength can be improved through supervised therapy either before surgery or postoperatively.

Procedures

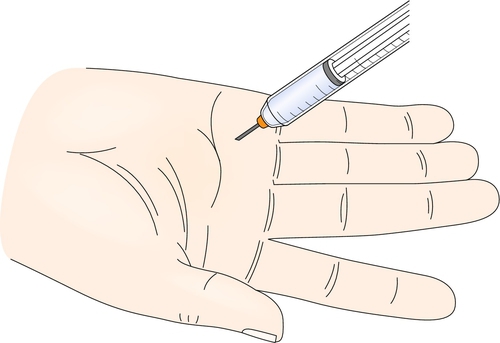

A local corticosteroid injection combined with local anesthetic (Fig. 37.2) can be used as an alternative or in addition to other management [19,20]. A splint can be worn after the injection for a few days, purportedly to help protect the injected area. Because it may take 3 to 5 days for the medication to take effect, the patient should be advised to avoid activities with the affected hand as much as possible for 1 week after the injection.

The injections are usually beneficial and frequently curative [21,22]. Although the most recent Cochrane review found a clear benefit of corticosteroid injection over placebo [23], the reported success rates have varied widely. One study reported a treatment success of 54% and improvement rate of 88% at 1 year after a single injection [24]. This procedure is less effective with involvement of multiple digits (such as in patients with diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis) or when the condition has persisted longer than 4 months [22].

Surgery

In adults, steroid injections should be tried for most trigger finger cases before surgery is considered. However, surgical intervention is highly successful for conservative treatment failures and should be considered for patients desiring quick and definitive relief from this disability [25]. Individuals with diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple joint involvement, and younger age at onset are more likely to require surgery [2,26].

There are two general types of surgery for this condition: the standard open operative release of the A1 pulley and the percutaneous A1 pulley release procedure. In one study using a percutaneous trigger finger release technique, the success rate was 100% at 12 weeks of follow-up [27]. Both surgical procedures are generally effective and carry a relatively low risk of complications [25,28].

Potential Disease Complications

Disease-related complications are rare and could include permanent loss of range of motion from development of a contracture in the affected finger, most commonly at the proximal interphalangeal joint [11]. More rarely, chronic intractable pain may develop despite treatment.

Potential Treatment Complications

Treatment-related complications from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are well known and include gastric, renal, and hepatic side effects. Complications from local corticosteroid injections include skin depigmentation, dermatitis, subcutaneous fat atrophy, tendon rupture, digital sensory nerve injury, and infection [29,30]. Individuals with rheumatoid arthritis are more likely to have a tendon rupture [31]; therefore repeated injections are not recommended in these cases. Possible surgical complications include infection, nerve injury, and flexor tendon bowstringing [32–34].