CASE 37 Inability to Stent in the Face of a Large Dissection

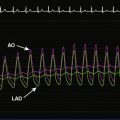

Cardiac catheterization

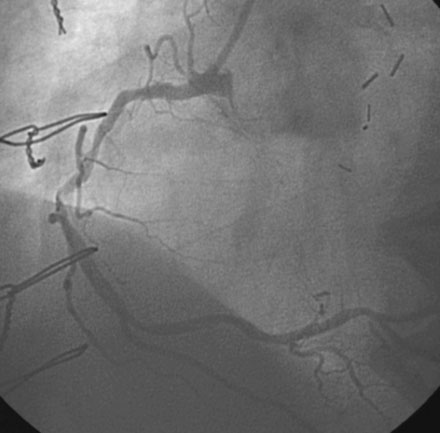

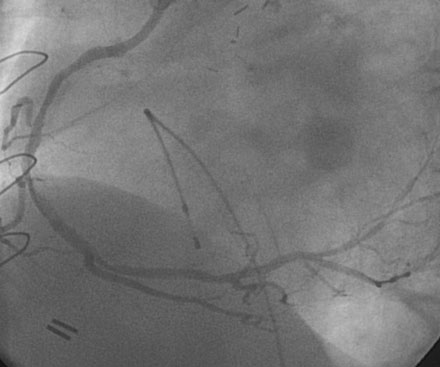

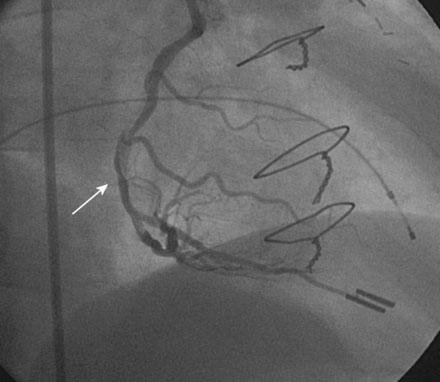

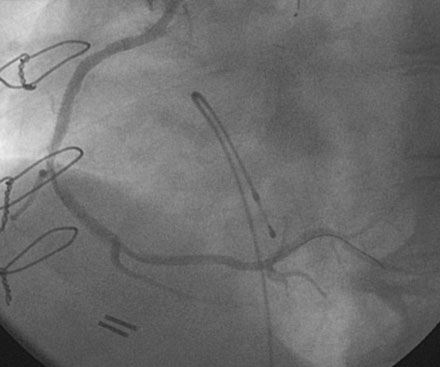

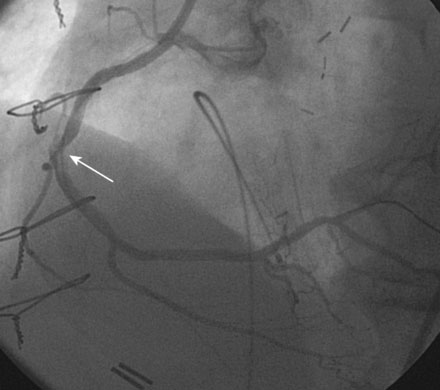

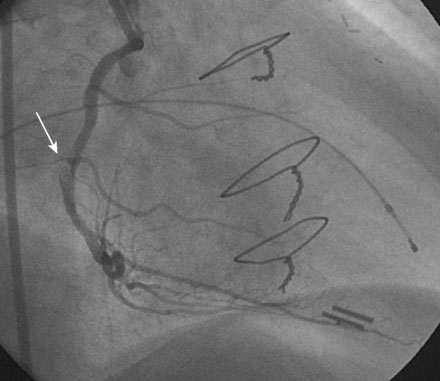

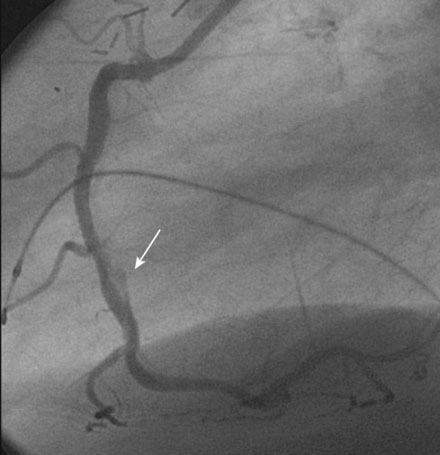

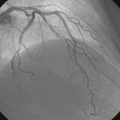

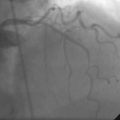

The left internal mammary graft to the LAD was intact and the LAD supplied collaterals to the circumflex (Video 37-1). The native LAD and circumflex were both occluded. Heavy calcification affected the right coronary artery and severe disease was present in the midsegment of this artery (Figures 37-1, 37-2 and Videos 37-2, 37-3). Because of extensive calcification, rotational atherectomy was planned. This was performed with a 1.5 mm burr through an 8 French right Judkins guide catheter after a temporary pacemaker was placed and procedural anticoagulation was achieved with unfractionated heparin and eptifibatide. Following rotational atherectomy, balloon angioplasty using a compliant, 2.5 mm diameter by 20 mm long balloon was accomplished at several locations within the mid-right coronary, and full inflation of the balloon was noted at nominal inflation pressures (Figure 37-3). The angiogram obtained after rotational atherectomy and balloon angioplasty is shown in Figures 37-4 and 37-5 and Videos 37-4 and 37-5. While the left anterior oblique projections appeared acceptable, the right anterior oblique projection revealed a large dissection in the midsection.

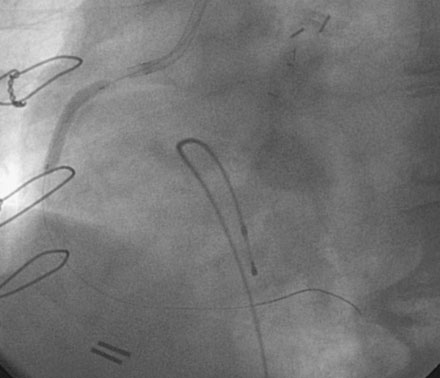

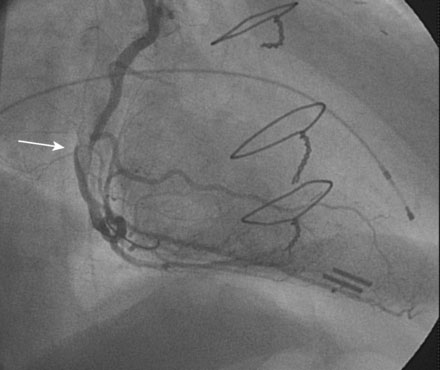

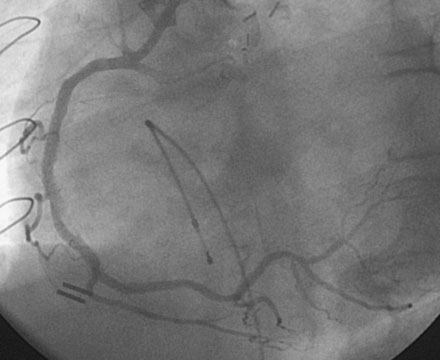

The operator then attempted to advance a stent (3.0 mm diameter by 20 mm long paclitaxel-eluting stent) to the mid-right coronary lesion with the goal of covering the entire dissection. However, the stent would not advance to the desired location. The operator decided to withdraw this stent and try a shorter, bare-metal stent; however, the first stent was firmly embedded in the lesion and would not withdraw to the guide. The operator feared that the stent might come off the balloon if additional force was applied and deployed the stent at the location, it became trapped (Figure 37-6). The angiogram obtained after this stent was deployed proximal to the desired location is shown in Figure 37-7. This stent was then aggressively postdilated with a noncompliant balloon and the unstented lesion in the midportion of the artery aggressively ballooned with a noncompliant balloon to high pressures after an additional and more supportive guidewire was placed as a “buddy” wire to facilitate another attempt at stent placement. The operator then chose a 3.0 mm diameter by 8 mm long bare-metal stent. With great difficulty, this stent was advanced distally, covering the distal part of the dissection (Figure 37-8 and Video 37-6); however, there remained a prominent dissection proximal to this in the midsegment of the artery. Again, the operator aggressively ballooned this area with noncompliant balloons. While the angiographic result appeared acceptable in the left anterior oblique projection (Video 37-7), the prominent dissection was most apparent in the right anterior oblique projection and narrowed the lumen significantly (Figure 37-9 and Video 37-8). One additional 3.0 mm diameter by 8 mm long bare-metal stent was advanced through the proximal stent and covered an additional portion of the dissection, but the operator could not pass this third stent far enough to cover the dissection completely. Despite aggressive ballooning, additional attempts to completely cover the dissection by inserting yet another stent failed. The operator decided to stop the procedure after watching the patient for 15 minutes on the catheterization table and after observing no deterioration in the angiogram or the patient’s clinical status, or any change in the electrocardiogram. The final angiographic results are shown in Figures 37-10 through 37-12 and Videos 37-9 and 37-10.

Discussion

The decision to leave a dissection alone depends upon the anticipated risk of vessel closure or other adverse event. The angiographic appearance of coronary dissections can be classified according to the system described by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institutes (Table 37-1). Using this classification scheme, the outcomes of 691 coronary dissections from the balloon era (1987-1990) were determined.1 Type A dissections are of no clinical consequence and were not studied. The incidence of adverse events such as emergency bypass surgery and abrupt vessel closure were very low for Type B dissections. However, Type C through F dissections had a substantially higher incidence of adverse events. The risk of abrupt vessel closure and emergency bypass surgery was nearly 10% for Type C dissections and was between 30% and 60% for the more serious Type D, E, and F dissections.1 Overall procedural success in this series was 93.7% for Type B dissections (similar to patients without angiographically evident dissections), and was only 38% for patients with Type C through F dissections. Although this information is derived from the balloon angioplasty era and may have little relevance in predicting outcomes in the current era with its advances in pharmacology, this information assists the operator in predicting the risk of vessel closure in cases of a dissection that cannot be stented.

| Type | Angiographic Description |

|---|---|

| A | Radiolucency within lumen during contrast injection with minimal or no persistent contrast staining |

| B | Parallel tracts or double lumen separated by radiolucency during injection with minimal or no persistent contrast staining |

| C | Contrast outside the lumen with persistent staining after clearance of dye injection |

| D | Spiral luminal filling defects with extensive contrast staining |

| E | Intraluminal filling defects with > 50% luminal obstruction |

| F | Dissection with closure |

The dissection noted in this case would be classified as a Type E dissection with a high likelihood of closure if left untreated. Despite the presence of an unstented dissection, the patient actually did very well, but this is likely because stents were successfully delivered on either side of the dissection and because glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were used, both of which might have altered the natural history of this type of dissection. Although the patient had a favorable acute outcome, the presence of an unstented dissection adjacent to successfully deployed coronary stents is a risk factor for stent thrombosis.2,3 Whether this concern justifies a more aggressive approach and is an indication for surgery is unclear.

1 Huber M.S., Mooney J.F., Madison J., Mooney M.R. Use of a morphologic classification to predict clinical outcome after dissection from coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:467-471.

2 Lemeslea G., Delhaye C., Bonello L., de Labriolle A., Waksman R., Pichard A. Stent thrombosis in 2008: Definition, predictors, prognosis and treatment. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;101:769-777.

3 Cheneau E., Leborgne L., Mintz G.S., et al. Predictors of subacute stent thrombosis: Results of a systematic intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2003;108:43-47.