Procedure 36 Syndactyly Release

![]() See Video 29: Syndactyly Release and Skin Grafting

See Video 29: Syndactyly Release and Skin Grafting

See Video 30: Syndactyly Release with Pentagonal Flap

Indications

Syndactyly release is indicated to improve aesthetic appearance, alleviate functional limitations, and prevent deformity due to growth restriction.

Syndactyly release is indicated to improve aesthetic appearance, alleviate functional limitations, and prevent deformity due to growth restriction.

Syndactyly release is usually performed between 12 and 18 months of age when the anatomic structures are larger and anesthesia is safer compared with younger ages. Long-term results are not compromised by waiting longer, although it is preferable to complete surgery before the child enters nursery school. An earlier release at about 6 months of age should be considered in children with syndactyly of the fourth web because the difference in length of the ring finger and small finger can lead to angulatory and rotatory deformities. Similarly, in children with complicated syndactyly, the first web space should be released at an earlier age.

Syndactyly release is usually performed between 12 and 18 months of age when the anatomic structures are larger and anesthesia is safer compared with younger ages. Long-term results are not compromised by waiting longer, although it is preferable to complete surgery before the child enters nursery school. An earlier release at about 6 months of age should be considered in children with syndactyly of the fourth web because the difference in length of the ring finger and small finger can lead to angulatory and rotatory deformities. Similarly, in children with complicated syndactyly, the first web space should be released at an earlier age.

If the syndactyly involves more than one web space, it is safer to release contiguous web spaces at separate stages to avoid disrupting the blood supply to the finger between the web spaces.

If the syndactyly involves more than one web space, it is safer to release contiguous web spaces at separate stages to avoid disrupting the blood supply to the finger between the web spaces.

Examination/Imaging

Clinical Examination

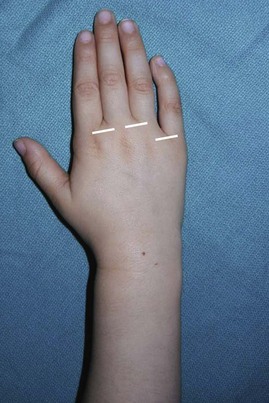

Syndactyly is classified by the extent of fusion and the elements that are fused. Complete syndactyly involves the entire length of the fingers from the web to the tip (Fig. 36-1), whereas incomplete does not involve the entire length (Fig. 36-2). Simple syndactyly involves fusion of the skin only. Complex syndactyly describes fusion of the phalanges, usually the distal phalanx. Complicated syndactyly refers to fusion of multiple digits and is typically associated with other congenital anomalies such as Apert or Poland syndrome (Fig. 36-3).

Syndactyly is classified by the extent of fusion and the elements that are fused. Complete syndactyly involves the entire length of the fingers from the web to the tip (Fig. 36-1), whereas incomplete does not involve the entire length (Fig. 36-2). Simple syndactyly involves fusion of the skin only. Complex syndactyly describes fusion of the phalanges, usually the distal phalanx. Complicated syndactyly refers to fusion of multiple digits and is typically associated with other congenital anomalies such as Apert or Poland syndrome (Fig. 36-3).

Surgical Anatomy

The web space is U shaped, with a 45-degree slope from the metacarpal head to the midproximal phalanx (Fig. 36-6). The web space of the index and long finger is at the same level, whereas the web space of the fourth web is more proximal (Fig. 36-7).

The web space is U shaped, with a 45-degree slope from the metacarpal head to the midproximal phalanx (Fig. 36-6). The web space of the index and long finger is at the same level, whereas the web space of the fourth web is more proximal (Fig. 36-7).

General Principles

The new web space should be created more proximal than normal to account for web creep with growth of the child.

The new web space should be created more proximal than normal to account for web creep with growth of the child.

A flap should be used to resurface the web space. The use of skin grafts should be avoided in the web spaces.

A flap should be used to resurface the web space. The use of skin grafts should be avoided in the web spaces.

An interdigitating flap design should be used for coverage of digits. However, if primary flap closure is tight, there should be no hesitation in using a full-thickness skin graft.

An interdigitating flap design should be used for coverage of digits. However, if primary flap closure is tight, there should be no hesitation in using a full-thickness skin graft.

Procedure

Release of Simple Complete Syndactyly

Exposures

A proximally based dorsal rectangular flap for web reconstruction, along with interdigitating flaps, is used.

A proximally based dorsal rectangular flap for web reconstruction, along with interdigitating flaps, is used.

The proximally based dorsal rectangular flap is designed by marking the metacarpal heads and a point on each digit at the midpoint of the proximal phalanx. The points are connected to form a proximally based flap with its base at the level of the metacarpal heads (Fig. 36-8).

The proximally based dorsal rectangular flap is designed by marking the metacarpal heads and a point on each digit at the midpoint of the proximal phalanx. The points are connected to form a proximally based flap with its base at the level of the metacarpal heads (Fig. 36-8).

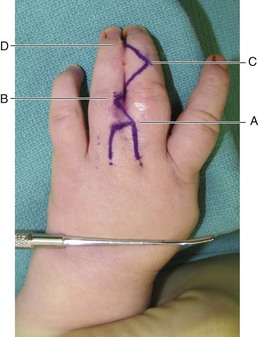

The interdigitating flaps are designed as two Zs, one on the dorsum and the other on the palmar surface, such that they form mirror images. The dorsal Z is designed first and connects the following four points sequentially (Fig. 36-9):

The interdigitating flaps are designed as two Zs, one on the dorsum and the other on the palmar surface, such that they form mirror images. The dorsal Z is designed first and connects the following four points sequentially (Fig. 36-9):

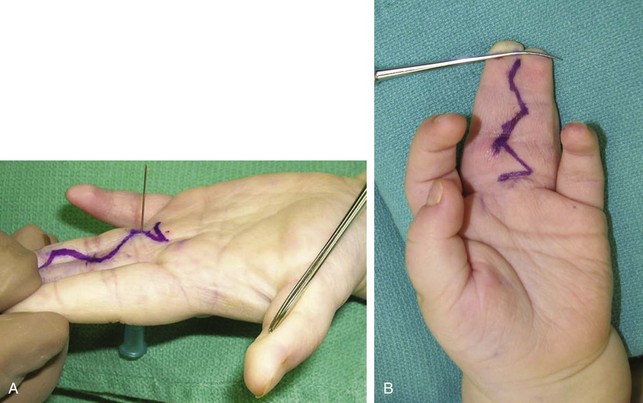

For the flaps to interdigitate, the tips of the palmar and dorsal Zs must oppose each other. A 25-gauge needle is inserted through the skin from the dorsum to the palmar surface at the same level as the tip of the proximal dorsal flap (point B), and a palmar flap is designed such that the tip is on the other finger (Fig. 36-10A). The remainder of the mirror palmar incision is then designed (Fig. 36-10B).

For the flaps to interdigitate, the tips of the palmar and dorsal Zs must oppose each other. A 25-gauge needle is inserted through the skin from the dorsum to the palmar surface at the same level as the tip of the proximal dorsal flap (point B), and a palmar flap is designed such that the tip is on the other finger (Fig. 36-10A). The remainder of the mirror palmar incision is then designed (Fig. 36-10B).

Step 1: Flap Elevation

Step 1 Pearls

Step 2: Separation of Digits

The distal fingertip with nail plate is divided sharply with tenotomy scissors (Fig. 36-13).

The distal fingertip with nail plate is divided sharply with tenotomy scissors (Fig. 36-13).

The longitudinal neurovascular structures are identified and protected (Fig. 36-14).

The longitudinal neurovascular structures are identified and protected (Fig. 36-14).

Tenotomy scissors are used to spread between the digits in a transverse direction as the fused digits are retracted laterally. The transverse fascial bands are identified and divided sharply. This dissection is begun distally and continued proximally until the digits are completely released at the level of the transverse intermetacarpal ligament, which is spared (Fig. 36-15).

Tenotomy scissors are used to spread between the digits in a transverse direction as the fused digits are retracted laterally. The transverse fascial bands are identified and divided sharply. This dissection is begun distally and continued proximally until the digits are completely released at the level of the transverse intermetacarpal ligament, which is spared (Fig. 36-15).

Step 3: Inset of Skin Flaps

Step 4: Harvest of Full-Thickness Skin Graft from the Groin

Areas that are not covered with these skin flaps are grafted with a full-thickness skin graft harvested from the groin (Fig. 36-19). An elliptical incision is made along the groin crease, and the skin and dermis are incised with a no. 15 scalpel.

Areas that are not covered with these skin flaps are grafted with a full-thickness skin graft harvested from the groin (Fig. 36-19). An elliptical incision is made along the groin crease, and the skin and dermis are incised with a no. 15 scalpel.

The skin and dermis are elevated sharply using a scalpel or tenotomy scissors. Any additional subcutaneous fat that is taken with the graft is removed sharply with tenotomy scissors.

The skin and dermis are elevated sharply using a scalpel or tenotomy scissors. Any additional subcutaneous fat that is taken with the graft is removed sharply with tenotomy scissors.

The skin graft is then cut to fill any additional defects not covered by the interdigitating flaps. It is preferable to leave fewer, larger gaps to be filled by a skin graft, rather than multiple small areas, because these will make it technically easier to contour the skin graft to the defect.

The skin graft is then cut to fill any additional defects not covered by the interdigitating flaps. It is preferable to leave fewer, larger gaps to be filled by a skin graft, rather than multiple small areas, because these will make it technically easier to contour the skin graft to the defect.

The skin graft donor site is closed using a few dermal sutures with absorbable suture, and the skin is approximated with chromic suture.

The skin graft donor site is closed using a few dermal sutures with absorbable suture, and the skin is approximated with chromic suture.

Step 4 Pearls

Scars in the groin invariably spread over time, regardless of the manner in which they are closed. Therefore, we prefer to close these wounds with a few dermal sutures and a simple running closure using a chromic suture. These scars can be revised at a later date if the patient desires (Fig. 36-20).

Procedure

Release of Simple Complete Syndactyly and Use of Dorsal Pentagonal Flap

Exposures

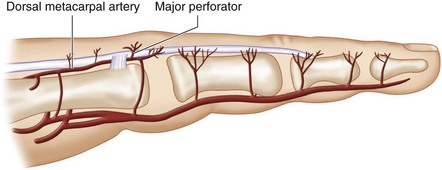

The dorsal pentagonal island flap is based on a constant cutaneous perforator of the dorsal metacarpal artery that arises in the intermetacarpal space at the level of the neck of the metacarpal (Fig. 36-21). This flap design is useful in patients who have a relatively lax simple syndactyly or an incomplete simple syndactyly, where it is felt that a skin graft may not be required for coverage of the digital raw areas. In such cases, the dorsal pentagonal flap is better than the standard proximally based dorsal rectangular flap because (1) a larger flap can be designed on the dorsum of the hand to resurface the web space and sides of the finger simultaneously, (2) the island design allows the flap to advance further than the standard proximally based flap, and (3) the lax dorsal skin permits primary closure of the flap donor site. However, the senior author does not use this flap design if a skin graft is required for coverage of the digit (e.g., tight syndactyly, complex syndactyly) because the time saved by doing this flap is negated by use of skin grafts. Additionally, a prominent dorsal scar is created.

The dorsal pentagonal island flap is based on a constant cutaneous perforator of the dorsal metacarpal artery that arises in the intermetacarpal space at the level of the neck of the metacarpal (Fig. 36-21). This flap design is useful in patients who have a relatively lax simple syndactyly or an incomplete simple syndactyly, where it is felt that a skin graft may not be required for coverage of the digital raw areas. In such cases, the dorsal pentagonal flap is better than the standard proximally based dorsal rectangular flap because (1) a larger flap can be designed on the dorsum of the hand to resurface the web space and sides of the finger simultaneously, (2) the island design allows the flap to advance further than the standard proximally based flap, and (3) the lax dorsal skin permits primary closure of the flap donor site. However, the senior author does not use this flap design if a skin graft is required for coverage of the digit (e.g., tight syndactyly, complex syndactyly) because the time saved by doing this flap is negated by use of skin grafts. Additionally, a prominent dorsal scar is created.

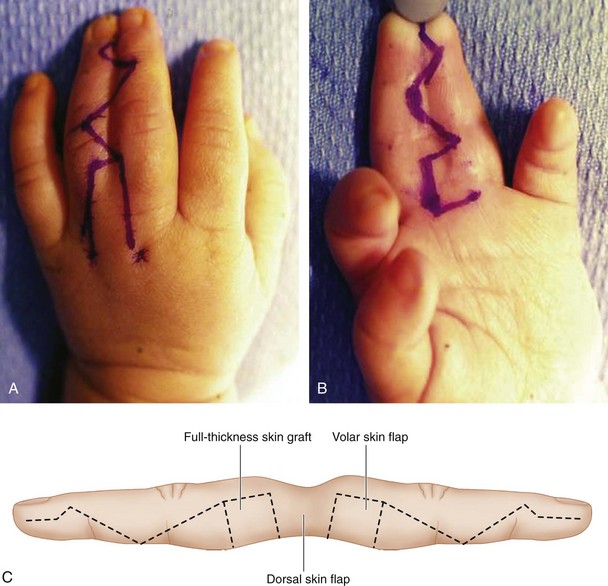

The flap is designed by marking the metacarpal heads and outlining a pentagonal flap to incorporate the perforating vessel that arises at the level of the metacarpal neck. This perforating vessel is not visualized in the flap elevation. The V-shaped portion of the flap is designed proximally for primary closure, and a curved incision is made 2 mm distal to the head of the metacarpals to match the curved incision over the volar web space (Fig. 36-22).

The flap is designed by marking the metacarpal heads and outlining a pentagonal flap to incorporate the perforating vessel that arises at the level of the metacarpal neck. This perforating vessel is not visualized in the flap elevation. The V-shaped portion of the flap is designed proximally for primary closure, and a curved incision is made 2 mm distal to the head of the metacarpals to match the curved incision over the volar web space (Fig. 36-22).

This flap is combined with interdigitating flaps as described previously (Fig. 36-23).

This flap is combined with interdigitating flaps as described previously (Fig. 36-23).

Step 1: Flap Elevation

Postoperative Care and Expected Outcomes

Dressings are applied to provide compression along the skin graft sites.

Dressings are applied to provide compression along the skin graft sites.

The hand is immobilized for 2 weeks to prevent shear injury to the grafts. Hand use may resume in 2 weeks when dressings are removed. No therapy is necessary in children, but scar massage exercises should be taught to the parents when the wound is healed to decrease scar thickness. If the web space is still not fully healed, parents must be taught to put Xeroform gauze between the fingers to prevent the open wounds from healing to each other.

The hand is immobilized for 2 weeks to prevent shear injury to the grafts. Hand use may resume in 2 weeks when dressings are removed. No therapy is necessary in children, but scar massage exercises should be taught to the parents when the wound is healed to decrease scar thickness. If the web space is still not fully healed, parents must be taught to put Xeroform gauze between the fingers to prevent the open wounds from healing to each other.

Pearls

Web creeping can occur with normal hand growth and can be prevented by releasing the border digits early in life and by overcompensating the web space deepening at the time of the procedure.

Arthrodesis can be performed in cases of complex syndactyly with joint instability or skeletal deformity, if the patient has reached skeletal maturity.

Pitfalls

Short-term complications following syndactyly release include skin necrosis, skin graft failure, digital nerve injury, and digital vessel injury resulting in digit ischemia.

In the long term, web creeping and scar contracture may occur, requiring revision surgery, including scar release and skin graft placement.

Chang J, Danton TK, Ladd AL, Hentz VR. Reconstruction of the hand in Apert syndrome: a simplified approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:465-470.

Lumenta DB, Kitzinger HB, Beck H, Frey M. Long-term outcomes of web-creep, scar quality, and function after simple syndactyly surgical release. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2010;35:1323-1329.

Sherif MM. V-Y dorsal metacarpal flap: a new technique for correction of syndactyly without skin graft. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:1861-1866.