CASE 36 Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease

PCI Versus CABG?

Cardiac catheterization

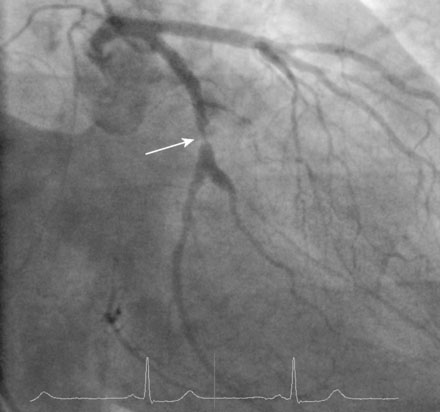

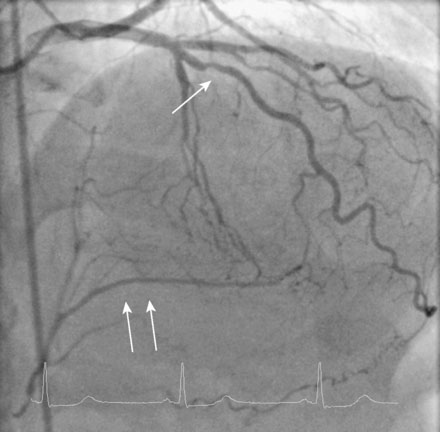

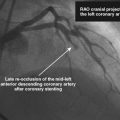

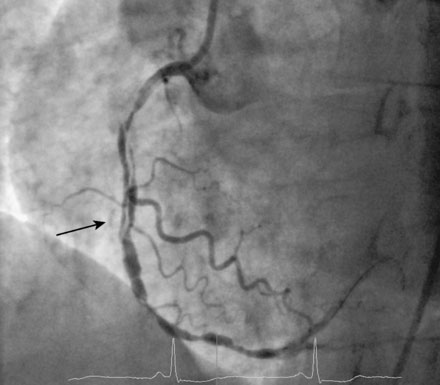

Ventriculography demonstrated moderate hypokinesis of the inferior wall, but global function was normal with an estimated ejection fraction of 60%. The right coronary artery was completely occluded and the duration of the occlusion could not be precisely determined (Figure 36-1 and Video 36-1). In the left coronary artery, a severe stenosis was identified in the midsegment of the left circumflex artery (Figure 36-2 and Video 36-2), and a stenosis of at least moderate severity was seen in the midsegment of the left anterior descending artery (Figure 36-3 and Video 36-3). The presence of well-developed left to right collaterals and the duration of symptoms suggested that the right coronary artery was chronically occluded and at least 3 months old.

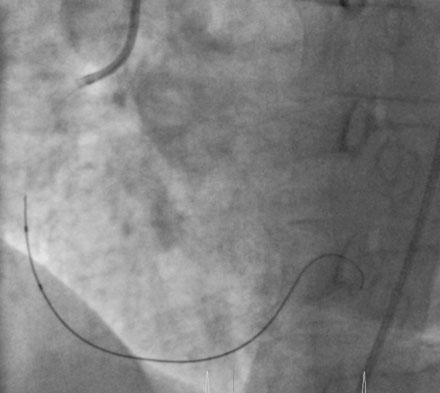

With this strategy in mind, the operator began with the right coronary artery. Procedural anticoagulation was accomplished with bivalirudin; the patient had already received pretreatment with 300 mg of clopidogrel the night before the procedure. After engaging a 6 French right Judkins guide catheter, the operator loaded a stiff-tipped 0.014 inch guidewire (Miracle Bros, 3, Asahi) into the lumen of a 2.5 mm diameter by 15 mm long, “over-the-wire,” compliant balloon catheter. The stiff-tipped guidewire easily crossed the occlusion and was advanced into the distal right coronary artery (Figure 36-4). The “over-the-wire” balloon was advanced distally and the stiff-tipped wire was removed and replaced by a floppy-tipped guidewire. Patency was restored after performing balloon angioplasty with the 2.5 mm balloon; however, the artery appeared diffusely diseased distally with an extensive dissection in the midsection (Figure 36-5 and Video 36-4). Multiple everolimus-eluting stents were placed, ranging in diameter from 2.5 mm distally to 3.5 mm proximally, covering 98 mm of length. The proximal and midsegments were postdilated with a 4.0 mm noncompliant balloon and an excellent final angiographic result was obtained (Figure 36-6 and Video 36-5).

FIGURE 36-5 Result after balloon angioplasty; there is extensive dissection and distal disease observed (arrow).

FIGURE 36-6 Final angiographic result after extensive stenting performed in the right coronary artery.

The procedure was stopped in order to conserve contrast volume and limit radiation exposure. The following day, the operator treated the circumflex artery with a 3.5 mm diameter everolimus-eluting stent without difficulty (Figure 36-7 and Video 36-6). Because the left anterior descending artery stenosis was of unclear significance, this lesion was assessed with a pressure wire to determine fractional flow reserve (Figure 36-8). Maximum vasodilation was achieved with an injection of 200 mcg of intracoronary adenosine and the fractional flow reserve was calculated to be 0.86, indicating that the lesion in the LAD was not hemodynamically significant; thus stenting was not performed (Figure 36-9).

FIGURE 36-8 Location of the pressure wire transducer (arrow) in the left anterior descending artery.

Discussion

The decision regarding which vessels to revascularize is typically made by a visual assessment of the angiogram. While this approach is certainly acceptable for lesions that are severely stenotic, treatment of a lesion that is ambiguous or moderately narrowed but not actually flow-limiting exposes the patient to increased risk without providing any benefit. Recently, the strategy of fractional flow reserve guided revascularization has been shown to be superior to angiographic guided therapy in patients with multivessel coronary disease undergoing stenting.1 In the case presented here, fractional flow reserve was very helpful and determined that the left anterior descending artery was non–flow-limiting and thus did not require treatment with a stent.

The controversy regarding multivessel intervention versus coronary bypass surgery has been debated for many years. In the balloon angioplasty era, numerous randomized controlled studies were performed comparing balloon angioplasty to bypass surgery; the largest study with the longest follow-up was the BARI trial.2 Similar to other related trials, the BARI study found no difference in death or myocardial infarction between patients treated with balloon angioplasty versus those undergoing bypass surgery. The main difference, also observed in earlier trials, was that patients undergoing balloon angioplasty had a higher rate of repeat revascularization procedures compared to patients undergoing bypass surgery.

Additional randomized controlled trials were repeated in the bare-metal stent era3–6 and the drug-eluting stent era.7,8 Again, the rate of death or MI was similar for groups treated with bare-metal stents compared to those treated with bypass surgery. Although stents reduced the rate of restenosis compared to balloon angioplasty, and drug-eluting stents reduced restenosis rates compared to bare-metal stents, the stent-treated groups continued to have higher rates of repeat revascularization compared to the groups treated with bypass surgery. Of interest, in the large-scale, randomized SYNTAX trial, a higher rate of stroke was observed for patients treated with coronary bypass surgery compared to PCI (2.2% vs. 0.6%).8

1. Tonino P.A.L., De Bruyne B., Pijls N.H.J., Siebert U., Ikeno F., van’t Veer M., Klauss V., Manoharan G., Engstrom T., Oldroyd K.G., Ver Lee P.N., MacCarthy P.A., Fearon W.F., FAME Study Investigators. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. For the N Engl J Med 2009;360:213-224

2. The Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI) Investigators. Comparison of coronary bypass surgery with angioplasty in patients with multivessel disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:217-225.

3. Serruys P.W., Unger F., Sousa J.E., Jatene A., Bonnier H.J.R.M., Schonbergern J.P.A.M., Buller N., Bonser R., van den Brand M.J.B., van Herwerden L.A., Morel M.A.M., van Hout B.A., Arterial Revascularization Therapies Study Group. For the N Engl J Med 2001;344:1117-1124.

4. Serruys P.W., Ong A.T.L., van Herwerden L.A., Sousa J.E., Jatene A., Monnier J.J.R.M., Schonberger J.P.M.A., Buller N., Bonser R., Disco C., Backx B., Hugenholtz P.G., Firth B.G., Unger F. Five-year outcomes after coronary stenting versus bypass surgery for the treatment of multivessel disease. The final analysis of the Arterial Revascularization Therapies Study (ARTS) randomized trail. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:575-581.

5. Morrison D.A., Sethi G., Sacks J., et alInvestigators of the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study #385. The Angina with Extremely Serious Operative Mortality Evaluation (AWESOME). For the J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:143-149

6. The SOS Investigators. Coronary artery bypass surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention with stent implantation in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease (the Stent or Surgery trial): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:965-970.

7. Park D.W., Yun S.C., Lee S.W., Kim Y.H., Lee C.W., Hong M.K., Kim J.J., Choo S.J., Song H., Chung C.H., Lee J.W., Park S.W., Park S.J. Long-term mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stent implantation versus coronary artery bypass surgery for treatment of multivessel coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2008;117:2079-2086.

8. Serruys P.W., Morice M.C., Kappetein A.P., Colombo A., Holmes D.R., Mack M.J., Stahle E., Feldman T.E., van den Brand M., Bass E.J., Van Dyck N., Leadley K., Dawkins K.D., Mohr F.W., SYNTAX Investigators. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. For the N Engl J Med 2009;360:961-972