CASE 36

History: An 80-year-old man with oxygen- and steroid-dependent chronic obstructive airway disease develops dysphagia and odynophagia.

1. Which of the following should be included in the differential diagnosis of the dominant imaging finding on figure A? (Choose all that apply.)

D. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) esophagitis

2. Which of the following distinguishes esophageal Candida infection in an immunocompromised patient from the same occurring in an immunocompetent host?

D. The infection is identical in both the immunocompromised and the immunocompetent patient.

3. Which of the following statements about esophageal Candida infection is true?

A. Candida albicans is the most common cause of infectious esophagitis.

B. Most of the patients with Candida esophagitis also have clinically visible oropharyngeal thrush.

4. Skin conditions may be associated with multiple tiny esophageal nodular lesions. Which of the following skin conditions is not associated with esophageal nodules?

ANSWERS

CASE 36

Esophageal Candida

1. A, B, C, and E

2. C

3. A

4. D

References

Levine MS, Rubesin SE. Diseases of the esophagus: diagnosis with esophagography. Radiology. 2005;237:414–427.

Cross-Reference

Gastrointestinal Imaging: THE REQUISITES, 3rd ed, p 7.

Comment

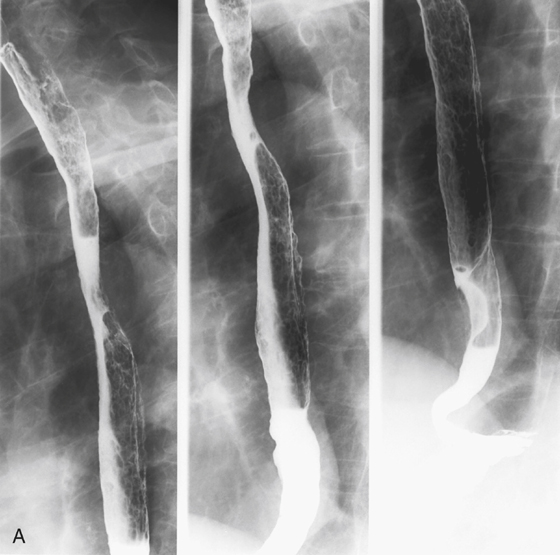

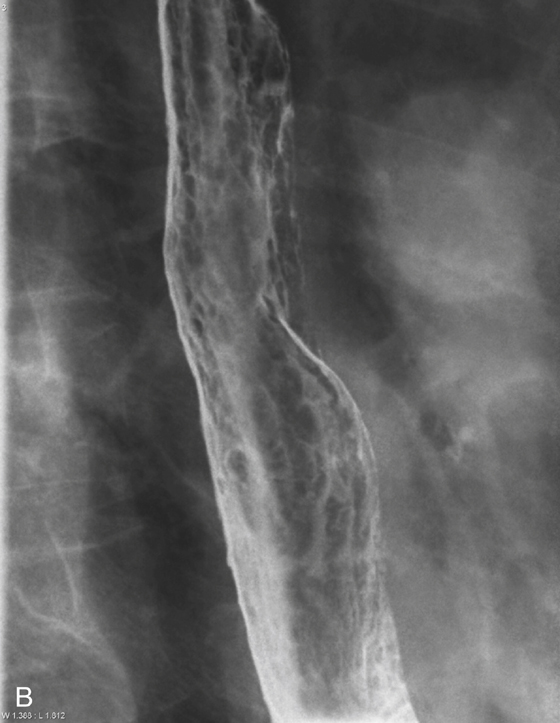

Numerous small plaques or nodules of the esophageal mucosa are not an uncommon finding. A variety of conditions can produce these abnormalities. Often the correct diagnosis can be made based on the clinical information provided by the patient. These nodules are either diffuse or focal, and this determination has some bearing on the diagnostic possibilities.

The numerous filling defects commonly seen in the esophagus are usually a technical issue. Having the patient drink barium along with the CO2 granules almost invariably yields this artifact. It is advisable to give the granules first, with a small amount of water immediately after.

Several infectious and inflammatory conditions can produce this true mucosal filling defect in the esophagus. The most important is Candida infection. These small, well-defined plaques, which are identified by the radiologist, correspond to the whitish ovoid or rounded plaques that are seen in the back of the pharynx of patients with thrush. Early on, they seem to line up on the longitudinal fold of the esophagus. This is usually referred to as the colonization stage. Later, as rhizoid extension into the mucosa and submucosa occurs, some ulceration may be detected (ulceration stage) and the patient experiences odynophagia. With progression of the ulceration stage, widespread diffuse ulceration and bleeding occur throughout the esophagus (the “shaggy” esophagus). Typically in the colonization phase the superficial plaques are only a few millimeters in diameter, but they can increase quickly to as large as 1 cm or more in diameter. In addition to immunocompromised patients, patients with scleroderma, achalasia, and other conditions associated with stasis of the esophageal contents can have Candida organisms visible on radiologic studies.

Reflux esophagitis can produce plaque-like elevations in the distal esophagus, and these growths correspond to areas of edema and inflammation without ulceration. Very rarely, herpetic esophagitis also produces multiple small nodular lesions. However, herpetic involvement is usually tiny punctuate ulcers rather than plaques.

A common benign condition of the esophagus is glycogenic acanthosis. This condition, which consists of swelling of the epithelium caused by increased cytoplasmic glycogen, predominantly affects the elderly. It is believed to be a degenerative phenomenon and of little or no clinical significance.

Some malignant and premalignant conditions also produce multiple plaques. Rarely, early esophageal cancer occurs as a focal area of irregular, variously sized raised plaques, without a discrete mass. Superficial spreading carcinoma of the esophagus can have more-diffuse nodules. Leukoplakia is a premalignant condition of the mouth that sometimes is found in the esophagus. Esophageal papillomatosis can be seen with acanthosis nigricans of the skin.