CASE 36

1. What etiologies can cause this finding? (Choose all that apply.)

A. Uremia

B. Hemorrhage

D. Tuberculosis

2. Which structure is calcified?

C. Valve

D. Pericardium

3. Given the symptoms, what is the most likely diagnosis?

C. Tamponade

D. Tumor

4. What is the most appropriate treatment?

A. Antibiotics

ANSWERS

References

Gowda RM, Boxt LM. Calcifications of the heart. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42(3):603–617.

Walker CM, Reddy GP, Steiner RM. Radiology of the heart. In: Rosendorff C, ed. Essential Cardiology. ed 3 New York: Springer; 2013.

Cross-Reference

Cardiac Imaging: The REQUISITES, ed 3, pp 10, 79–82.

Comment

Calcific Pericarditis

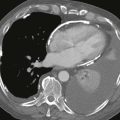

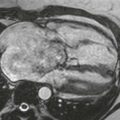

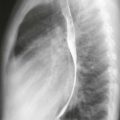

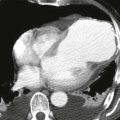

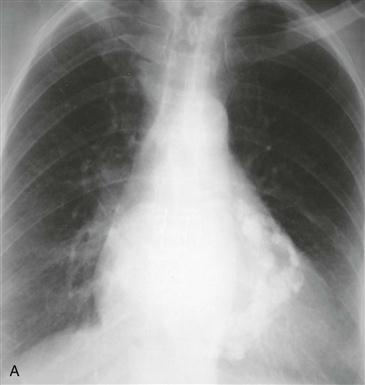

Chronic pericarditis can occur after uremic pericarditis, viral or tuberculous infection, radiation therapy, or open heart surgery. In chronic pericarditis, pericardial calcification most often results from tuberculosis. Because tuberculous pericarditis is rare in industrialized countries, pericardial calcification (Figs. A and B) occurs in less than 20% of patients with chronic pericarditis. Calcific pericarditis does not cause symptoms of constriction.

Constrictive Pericarditis

In the setting of chronic pericarditis, a patient may have constrictive pericarditis. Constrictive pericarditis is difficult to distinguish from restrictive cardiomyopathy. If a patient has constrictive or restrictive physiology, characterized by dyspnea, lower extremity edema, pleural effusions, and ascites, imaging studies can be used to differentiate constrictive pericarditis from restrictive cardiomyopathy. Pericardial thickening of at least 4 mm (best seen on MRI or CT), pericardial calcification (Figs. A and B), or abnormal diastolic septal motion (“bounce”) establishes the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis.