CASE 35 Left Main Dissection

Case presentation

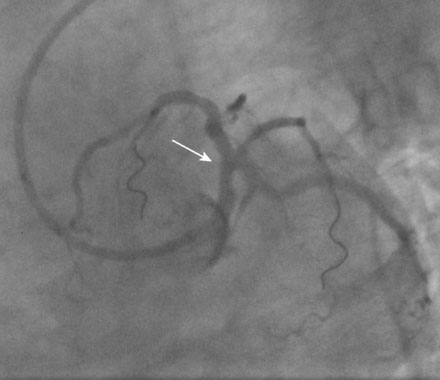

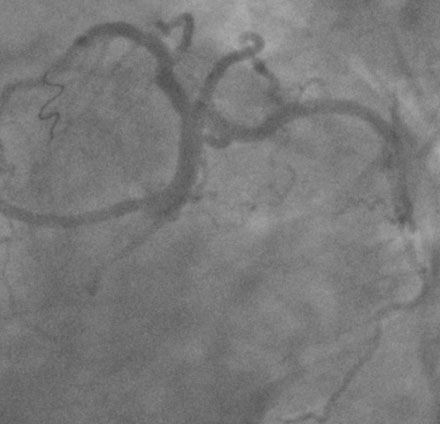

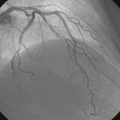

After presenting to the hospital with a 3-day history of intermittent chest pain and diaphoresis and found to have a non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, a healthy 49-year-old woman, with the coronary risk factors of tobacco abuse and dyslipidemia, underwent cardiac catheterization and was found to have a severe stenosis in the ramus intermedius branch (Figures 35-1, 35-2 and Video 35-1). Her other coronary arteries showed no angiographic evidence of significant atherosclerotic disease. She was subsequently referred for percutaneous treatment of the ramus intermedius branch.

Cardiac catheterization

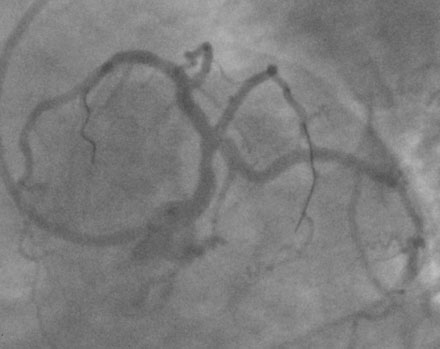

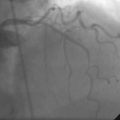

After passing the wire successfully and predilating the ramus lesion with a 2.0 mm diameter by 12 mm long compliant balloon, the operator happened to note an unexpected narrowing of the distal left main stem and positioned another 0.014 inch floppy-tipped guidewire into the left anterior descending artery (Figure 35-3 and Video 35-2). Several intracoronary boluses of nitroglycerin did not change the appearance of the distal left main narrowing. The physician proceeded with stenting of the ramus lesion using a 2.25 mm diameter by 16 mm long paclitaxel-eluting stent (Figure 35-4 and Videos 35-3, 35-4). The narrowing of the distal left main stem remained unchanged throughout the procedure on the ramus intermedius.

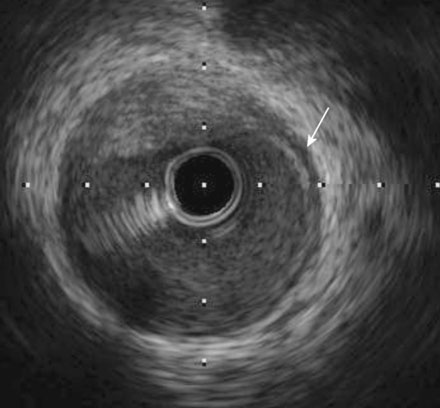

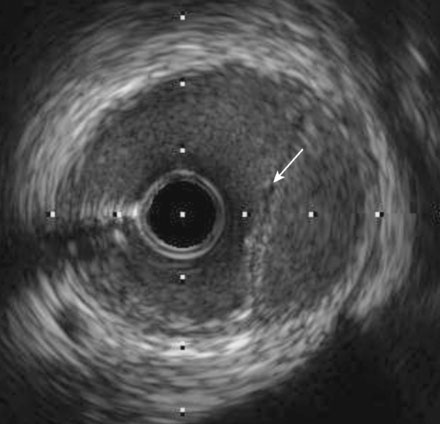

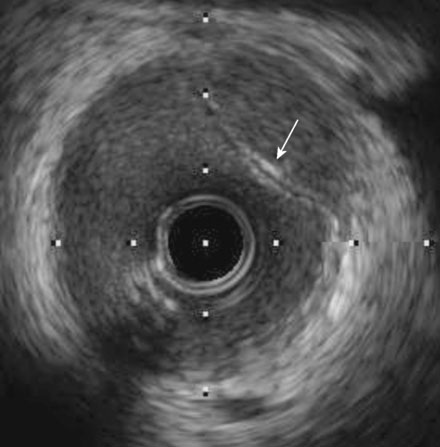

In order to determine both the mechanism and extent of the distal left main stem luminal narrowing, intravascular ultrasound was performed. The ultrasound catheter was pulled back from the ramus to the ostium of the left main (Video 35-5). At the distal end of the left main, an intramural hematoma was clearly apparent (Figure 35-5). More proximally, discrete intimal flaps were present and occupied almost 50% of the left main lumen (Figures 35-6, 35-7). Based on the ultrasound images, the operator decided to stent the injured segment of the left main stem with a 4.0 mm diameter by 12 mm long paclitaxel-eluting stent, thus restoring the vessel to a normal angiographic appearance (Figure 35-8 and Video 35-6). Repeat intravascular ultrasound assessment confirmed excellent stent apposition and wide luminal patency of the left main stem.

Discussion

Guide-related injuries of the left main stem or proximal right coronary artery during percutaneous intervention are uncommon and usually caused by large-bore guide catheters with aggressive curves, lack of coaxial engagement, deep engagement in the coronary ostium to provide backup, and presence of underlying atherosclerosis.1,2 Although possible, in this case, it does not appear that the guide catheter caused the intimal injury, as there was no evidence of a dissection by angiography. The major cause of this injury was likely due to the guidewire. The tip probably penetrated the intima and entered the subintimal space, creating an intimal flap and an intramural hematoma.

1 Mulvihill N.T., Boccalatte M., Fajadet J., Marco J. Catheter-induced left main dissection: A treatment dilemma. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003;58:214-216.

2 Al-Saif S.M., Lie M.W., Al-Mubarak N., Agrawal S., Dean L.S. Percutaneous treatment of catheter-induced dissection of the left main coronary artery and adjacent aortic wall: A case report. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2000;49:86-89.