CHAPTER 35

Kienböck Disease

Definition

Kienböck disease is avascular necrosis of the lunate, unrelated to acute fracture, often leading to fragmentation and collapse. Although the precise etiology and natural history of this disorder remain unknown, interruption of the blood supply to the lunate is undoubtedly a part of the process. Trauma has been implicated as a cause [1–3]. This disease occurs most often in the dominant hand of men in the age group of 20 to 40 years. Many of these patients are manual laborers who report a history of a major or repetitive minor injury. Associations have also been made between Kienböck disease and corticosteroid use, cerebral palsy, systemic lupus erythematosus, sickle cell disease, gout, and streptococcal infection.

An important radiographic observation has been made regarding the radius-ulna relationship at the wrist and the development of Kienböck disease [4]. In these patients, the ulna is generally shorter than the radius, a finding termed ulnar negative (or minus) variance. Normally, the lunate rests on both the radius and the triangular fibrocartilage complex covering the ulnar head. It has been speculated that when the ulna is significantly shorter than the radius, a shearing effect occurs in the lunate, which can make it more susceptible to injury.

Symptoms

Presenting symptoms include chronic wrist pain, decreased range of motion, and weakness [5]. The pain is usually deep within the wrist, although the patient often points to the dorsum of the wrist, and is aggravated by activity. Some patients complain of a pressure-like pain that may awaken them. A history of recent trauma is often provided; however, many patients report having had long-standing mild wrist pain preceding the recent injury. Symptoms may often be present for months or years before the patient seeks medical attention.

Physical Examination

Mild dorsal wrist swelling and tenderness in the mid-dorsal aspect of the wrist may be present. Wrist flexion and extension are limited. Forearm rotation is usually preserved. Grip strength is often considerably less on the affected side because of pain.

Neurologic and vascular examination findings are normal.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations include difficulty with heavy lifting, gripping, and activities involving the extremes of wrist motion. Many heavy laborers are unable to perform the essential tasks required of their occupation.

Diagnostic Studies

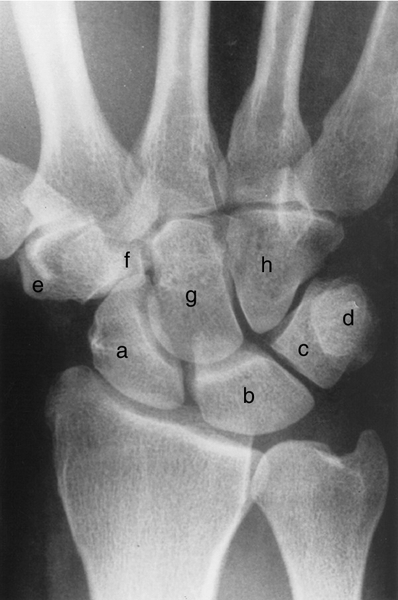

The initial diagnostic imaging for suspected Kienböck disease includes standard wrist radiographs. Early in the disease process, the radiographs may be normal. With time, a characteristic pattern of deterioration occurs, beginning with sclerosis of the lunate, followed by fragmentation, collapse, and finally arthritis [6,7] (Fig. 35.1). A radiographic staging system for Kienböck disease, proposed by Lichtman, is helpful in describing the extent of the disease and guiding treatment [1] (Table 35.1).

Table 35.1

Stages of Kienböck Disease

| Stage I | Normal radiographs or linear fracture |

| Stage II | Lunate sclerosis, one or more fracture lines with possible early collapse on the radial border |

| Stage III | Lunate collapse |

| IIIA | Normal carpal alignment and height |

| IIIB | Fixed scaphoid rotation (ring sign), carpal height decreased, capitate migrates proximally |

| Stage IV | Severe lunate collapse with intra-articular degenerative changes at the midcarpal joint, radiocarpal joint, or both |

For clinical suspicion of Kienböck disease with normal radiographs, a technetium bone scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful. In fact, MRI has supplanted plain radiography for the detection and evaluation of the early stages of Kienböck disease when there has been no trabecular bone destruction. Characteristic signal changes include decreased signal on T1-weighted and increased signal on T2-weighted images (Fig. 35.2). Computed tomography is more effective than MRI in assessing for fracture of the lunate, but it provides limited information about its vascularity (Figs. 35.3 and 35.4).

Treatment

Initial

Given the limited information about the etiology and natural history of this uncommon disease, it is not surprising that the treatment has not been standardized. Without surgery, progressive radiographic collapse and radiographic arthritis almost invariably occur [5]. However, symptoms correlate only weakly with the radiographic appearance, and many patients maintain good long-term function even without surgery [8]. The goals of surgery ideally would be to relieve the pain and to halt the progression of the disease. Surgical interventions appear to be relatively effective in achieving the first goal but have not as yet reliably altered the radiographic deterioration of the lunate. Consequently, treatment options range from simple splints to external fixation and from radial shortening to vascularized grafts to fusions. Factors taken into consideration in assigning treatment include stage of the disease; ulnar variance; and age, occupation, pain, and functional impairment of the patient [9]. An argument can be made to treat young, active patients with early-stage disease more aggressively in an effort to prevent progression; however, intra-articular procedures invariably result in some permanent loss of motion.

Many clinicians prefer to begin with symptomatic treatment. Depending on the situation, this may involve a splint and activity modification or a short arm cast. However, an appropriate length of immobilization has not been established. Some clinicians have attempted this treatment for as long as 1 year, but most clinicians prescribe a cast for 6 to 12 weeks. The immobilization probably helps the pain associated with synovitis and with wrist activity and motion; however, it does nothing to alter the vascularity of the bone or the shear stresses across the lunate. The patient should be informed that the radiographs will, in all likelihood, demonstrate worsening of the disease over time.

Pain can be treated with analgesics, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Narcotic medications are generally not recommended because of the chronicity of this condition.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation does not play a major role early in conservative treatment. Once the pain has subsided, gentle range of motion and strengthening may be initiated. Therapy is important for the postoperative patient, particularly if an intra-articular procedure has been performed or an external fixator has been applied. The wrist is typically immobilized postoperatively until the vascularized graft or fusion has healed (about 6 weeks). At that point, occupational or physical therapy can effectively begin with gentle range of motion exercises, gradually progressing to strengthening exercises.

Procedures

Intra-articular steroids are of no proven benefit in the management of Kienböck disease.

Surgery

Some authors think that most patients treated nonoperatively do well [6], whereas others think that surgery is indicated for most patients with Kienböck disease [10–12]. The surgical treatment options for this disease may be divided into stress reduction (unloading), revascularization, lunate replacement, and salvage procedures [9]. Radial shortening of 2 to 3 mm is currently the most popular procedure for early-stage Kienböck disease in the setting of ulnar minus variant [10,13]. The goal is to make the radius and ulna lengths the same and thus to reduce shear forces on the lunate. Other unloading procedures include limited wrist fusion, capitate shortening, and external fixation [14]. Revascularization procedures have shown promise in the management of avascular necrosis of the lunate [15,16]. The most popular of the pedicled bone grafts, based on the extensor compartmental arteries of the wrist, is transplanted from the distal radius into the lunate. In one series with relatively short-term follow-up, significant pain relief was observed in 92% of patients, and actual lunate revascularization was seen in 60% on follow-up MRI [15]. An intriguing method of indirect revascularization of the lunate has been proposed by Illarramendi and colleagues [17], who perform a metaphyseal drilling of the radius and ulna, without violating the wrist joint. In their series, 16 of 20 patients were pain free at an average of 10 years postoperatively. Silastic lunate replacement has been abandoned because of implant dislocation and synovitis.

When the lunate has collapsed to the point that it is not reconstructable, salvage procedures such as proximal row carpectomy and partial or total wrist arthrodesis are considered. Obviously, these procedures sacrifice motion in an effort to provide pain relief. The results of the various procedures are dependent, to some extent, on the stage of the disease. Wrist arthroscopy may be of some benefit in determining the extent of the disease and in selecting the appropriate salvage procedure [18]. Regardless of the specific type of salvage procedure, most authors report 70% to 100% satisfaction of patients. Advanced arthritis (stage IV) is generally best treated with a total wrist arthrodesis.

Potential Disease Complications

Without surgery, progressive radiographic collapse of the lunate and arthritis of the wrist invariably occur.

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Infection is uncommon after hand surgery. Complications such as nerve injury, painful hardware, and stiffness of the wrist and digits are inherent in hand surgery. A radial shortening osteotomy or partial wrist fusion may fail to heal (nonunion). Secondary wrist arthritis can develop after partial wrist fusions or proximal row carpectomy. Grip strength virtually never returns to normal. Finally, and most important, whether surgery favorably alters the natural history of this rare condition remains unproven.