CHAPTER 33

Hand Osteoarthritis

Definition

Osteoarthritis of the hand is a degenerative condition of hyaline cartilage in diarthrodial joints. It is distinct from inflammatory arthropathies, such as rheumatoid arthritis, in which the primary component is an inflammatory or systemic pathophysiologic process. Idiopathic osteoarthritis excludes post-traumatic arthritis or arthritic conditions resulting from pyrophosphate deposition disease, infection, or other known causes. It is associated with aging, but variations in onset and severity seem genetically determined [1]. In particular, the early onset of osteoarthritis of the distal interphalangeal and trapeziometacarpal joints is genetically mediated separate from osteoarthritis at other joints; in other words, a 50-year-old person with severe hand arthritis is not at risk for early hip arthritis. The prevalence of osteoarthritis of the hand increases with age and is more common in men than in women until menopause. In individuals older than 65 years, osteoarthritis of the hand has been estimated to be as high as 78% in men and 99% in women [2]. The distal interphalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints and the base of the thumb are the most affected joints.

Symptoms

Patients typically report pain, stiffness, and disability. Symptoms follow a waxing and waning course as the disease gradually and inevitably progresses. The correlation between radiographic findings and pain intensity and magnitude of disability is limited, most likely as a reflection of the psychosocial factors that mediate the difference between disease and illness and between impairment and disability. Psychological distress and ineffective coping strategies should be identified and addressed.

Physical Examination

Osteoarthritis is insidious. Although a joint “goes gray” during decades, patients often notice an acute onset of symptoms that can make it difficult for them to believe their problem is an expected slow deterioration. The hallmarks of physical examination are deformity, restriction of motion, pain, and crepitation. A careful examination of all of the joints notes any deformity, effusions, erythema, limitations in range of motion, and swelling. The findings on neurologic examination should be normal.

Interphalangeal Joints

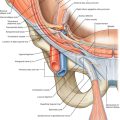

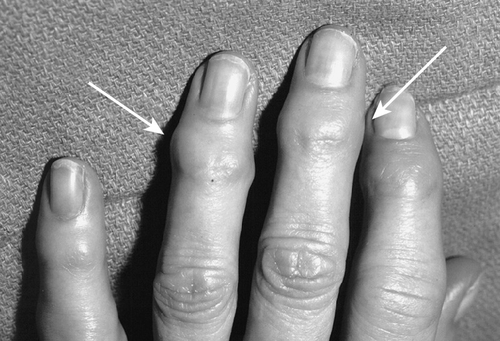

Osteoarthritis of the distal interphalangeal joint is characterized by enlargement of the distal joint by osteophytes, forming the so-called Heberden node (Fig. 33.1). Angulatory and rotatory deformities of the terminal phalanx can develop (Fig. 33.2). Ganglion (or mucous) cysts are associated with osteoarthritis of the distal (and less commonly the proximal) interphalangeal joints. The pressure of these cysts on the germinal matrix can cause a groove in the fingernail. The proximal interphalangeal joint is less commonly involved than the distal joint. The enlargement and deformity at the proximal interphalangeal joint is referred to as a Bouchard node.

Metacarpophalangeal Joints

It is relatively uncommon for the metacarpophalangeal joints to be involved in primary idiopathic osteoarthritis. The presentation at this joint is usually characterized by complaints of pain and stiffness rather than deformity.

Trapeziometacarpal Joint

Arthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint is associated with aging. Among women aged 80 years and older, 94% have radiographic signs of arthritis; two thirds of these have severe joint destruction [3]. Men develop arthritis more slowly than women do, but by the age of 80 years, 85% have arthritis. The process progresses from subluxation and slight narrowing of the joint to osteophyte formation, deformity, and destruction of the joint [4]. As the disease progresses, the base of the metacarpal subluxates radially, there is an adduction contracture of the metacarpal toward the palm, and laxity and hyperextension of the metacarpophalangeal joint develop in compensation. Axial compression and rotation and shear (the compression test) will produce crepitation and reproduce symptoms [5,6]. Both active and passive movement is restricted. Grip and pinch strength gradually diminish. It is useful to screen for carpal tunnel syndrome and trigger thumb, both of which are common in this age group.

Functional Limitations

The classic forms of reported disability are activities that require a forceful grasp, such as opening a tight jar, turning a key, or opening a doorknob. Whereas fine motor tasks are often impaired by interphalangeal osteoarthritis, complaints of disability are far less common; perhaps because the disease is so gradual, most patients adapt.

Diagnostic Studies

Radiographs are rarely necessary to establish a diagnosis or to guide treatment; their chief use is for ruling out other pathologic processes and increasing the patient’s understanding and acceptance of the disease process. Characteristic findings are joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, osteophyte formation, and degenerative cyst formation in the subchondral bone. Eaton and Littler classified trapeziometacarpal arthritis into four radiographic stages [7]. In stage I, the articular contours are normal with no subluxation or joint debris. The joint space may be widened if an effusion is present. In stage II, there is slight narrowing of the thumb trapezial metacarpal joint, but the joint space and articular contours are preserved. Joint debris is less than 2 mm and may be present. In stage III, there is significant trapezial metacarpal joint destruction with sclerotic resistive changes and subchondral bone with osteophytes larger than 2 mm. Stage IV is characterized by pantrapezial arthritis in which both the trapezial metacarpal and scaphoid trapezial joints are affected.

Treatment

Initial

There are no proved disease-modifying treatments of osteoarthritis. All treatments take the form of either palliation (management) or salvage (e.g., arthrodesis or arthroplasty). Because osteoarthritis is so common (as people age, they all have some evidence of osteoarthritis to some degree) and at least annoying if not disabling, there is extensive marketing that suggests the disease can be modified, but there is no proof of this assertion. There is also no proof that exercise or activity accelerates osteoarthritis. Exercise and activity can improve muscle strength, proprioception, and range of motion. Physicians should be cautious about advising activity restriction because it can directly create or exacerbate disability in a patient who associates pain with joint damage. Activity restriction is a personal choice determined by desired comfort level; it is entirely appropriate to remain active in spite of painful, degenerated joints.

Non-narcotic analgesics (acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications) are useful for pain relief and safe enough for routine use in most patients. Some patients find ice, heat, or topical creams useful. Splints that immobilize arthritic joints (for instance, a hand-based thumb spica with the interphalangeal joint free for trapeziometacarpal arthritis) can provide symptomatic relief, but it must be made clear to the patient that they will not cure the disease or prevent progression by wearing them and that splint wear is optional. The interphalangeal joints are rarely splinted because of the associated functional limitations as well as infrequent requests by patients. Intra-articular injections of corticosteroids or hyaluronate [8] inconsistently provide temporary relief, but patients need to understand that these injections cannot cure the disease and that they must either cultivate effective coping mechanisms or elect salvage reconstructive surgery.

Rehabilitation

Patients can be taught alternative ways to perform tasks that are hindered by arthritis (Table 33.1). For instance, they can get a device that helps them open jars and a larger grip for pens and pencils; they can change their doorknobs to levers. Prefabricated and custom hand- or forearm-based thumb spica splints can diminish the pain of trapeziometacarpal arthritis and may be most useful during certain tasks. Therapeutic modalities such as paraffin baths may be beneficial for some people. Contrast baths and ice massage are economical modalities that may provide some relief.

Table 33.1

Basic Principles of Arthritis Management

| Understand pain | The pain does not reflect ongoing harm; it is the result of the existing, permanent disease process. Any rest or activity restriction is voluntary and intended to diminish pain. Patients should be encouraged to continue in painful activities that they value without feeling guilty, neglectful, or irresponsible. |

| Modify activities | Patients can be taught alternative, less painful, and easier ways to accomplish daily tasks that do not rely on painful joints. Jar openers, pen grips, and door levers rather than knobs can be useful modifications. |

| Maintain strength and range of motion | Patients are encouraged to continue both daily activities and sports and exercise as a means for preserving active range of motion and muscle conditioning. Daily activities may be supplemented with active range of motion exercises targeted for specific joints. |

| Use stronger muscles and larger joints | In addition, the patient can be taught to carry items close to the body or to cradle them in the entire arm to distribute loads, rather than relying on smaller muscles and joints of the hand to bear the entire load. |

| Use adaptive equipment or splints | The patient is provided with information on specific adaptive devices that are helpful in reducing or eliminating positions of deformity or stress on the smaller joints. Splints can be useful for limiting pain with specific activities. |

Minimal supervision is needed after simple trapeziectomy. Patients are allowed activities as tolerated, and motion returns with normal use over time. If the joint is immobilized with a Kirschner wire or ligament reconstruction is performed, the joint is protected in a cast or splint for at least 1 month. If the hand gets stiff, patients are instructed in active, self-assisted stretching exercises. Distal interphalangeal joint arthrodesis is protected with splinting until healing is apparent. Proximal interphalangeal joint arthroplasties start motion exercises as comfort allows with protection of healing ligaments as necessary.

Procedures

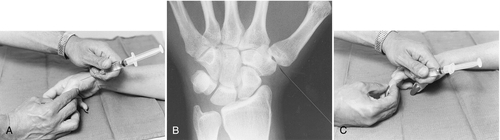

At best, an intra-articular injection of corticosteroids or hyaluronate will provide a few months of relief [9]. Serious complications, such as infection, are rare. The worst aspect of an injection is the disappointment felt by patients when their hoped-for miracle cure is not forthcoming or when the helpful injection (be it placebo or otherwise [10]) wears off after a few weeks to months. When the role of injections is accurately described, patients can make an informed decision. In my experience, patients do not find them very appealing. The number of corticosteroid injections at a single site is limited by the potential for skin discoloration, subcutaneous atrophy, and capillary fragility. I will not give more than three lifetime injections in the same area (Fig. 33.3).

Under sterile conditions, with use of a 25- to 27-gauge needle and a mixture of local anesthetic (e.g., 0.5 to 1 mL of 1% lidocaine) and corticosteroid (e.g., 0.5 to 1 mL of triamcinolone), the joint is injected. Small joints of the hand will not accommodate large volumes, so the total amount of fluid injected should typically be in the range of 1 to 2 mL. It is helpful to distract the joint by pulling on the finger.

Surgery

Osteoarthritis of the hand is a part of human development that all of us will experience if we are lucky to live long enough. Given the prevalence of arthritis, it is probably safe to assume that most patients adapt well to their arthritis, have effective coping skills, and never bring the arthritis to the attention of a physician. Among those who do bring the problem to a physician’s attention, most are satisfied with an explanation of the disease process, the reassurance that it is normal and inevitable, an understanding that the disease cannot yet be modified, and suggestions for management and palliation. Surgery provides fairly predictable pain relief, but in my experience, an informed patient who is involved in the decision infrequently requests operative treatment to reconstruct or to salvage the arthritic joint.

Distal Interphalangeal Joint

Infected mucous cysts are typically effectively treated with oral antibiotics (cephalexin or the equivalent to treat Staphylococcus aureus infection). Operative treatment is necessary only for long-standing cases with potential osteomyelitis. Because the joint is already severely damaged, there is no need to be concerned about joint damage from the infection.

Aspiration of mucous cysts is not expected to be curative. Patients sometimes elect aspiration to reduce the size of a very large cyst or to improve skin cover when it has become thin and translucent. The recurrence rate is also high after surgery. Patients must choose between leaving the cyst alone and making an attempt to resolve it with surgery, being mindful of the discomfort, inconvenience, and risks of surgery as well as the high recurrence rate.

Patients usually request arthrodesis when there is substantial ulnar or radial deviation of the distal interphalangeal joint. It is more aesthetic than functional. Patients rarely request distal interphalangeal joint arthrodesis for pain or disability.

Proximal Interphalangeal Joint

It is uncommon to operate on idiopathic osteoarthritis of the proximal interphalangeal joint, probably a reflection of the relatively low incidence and severity of osteoarthritis at this joint compared with the distal interphalangeal joint and effective coping with an insidious, slowly progressive disease. Arthrodesis and arthroplasty are both options at this joint and the indication is usually pain relief.

Arthrodesis is more predictable. Arthroplasty is used only in patients who are motivated to retain some mobility at the sacrifice of pain relief and stability [11]. Newer arthroplasties made of pyrolitic carbon (PyroCarbon) or metal have not proved superior to conventional Silastic rubber arthroplasty [12].

Trapeziometacarpal Joint

The trapeziometacarpal joint is the most common upper extremity site of surgical reconstruction for osteoarthritis. Operative treatment consists of the salvage procedures arthrodesis and resection arthroplasty [13,14]. Arthrodesis is less used because of the need for protection, the risk of nonunion, and the inability to place the hand flat on the table that is often bothersome to patients. Some surgeons favor arthrodesis in younger patients who use the hand for strength, but this recommendation is not evidence based.

Reconstruction of the palmar oblique ligament without resection of the trapezium and extension osteotomy of the metacarpal are controversial treatments for a painful trapeziometacarpal joint in a relatively young patient with limited radiographic signs of arthritis. Neither procedure is known to affect the natural history of the disease, and until it is demonstrated to be better than sham surgery, it should be considered to be strongly subject to the placebo or meaning effect, in my opinion [13]. Patients with laxity related to a connective tissue disorder are not helped by ligament reconstruction; their only option is arthrodesis, and it is elective.

There are many variations of resection arthroplasty [7,14,15]. The sources of variation include the following: the amount of trapezium resected; whether the palmar oblique ligament is reconstructed and what technique and tendon are used; what, if anything, is placed in the space created by trapeziectomy (rolled up tendon, prosthesis, or other commercial spacers); operative approach (volar, direct radial, arthroscopic); pinning of the joint; and tendons used or included in the reconstruction. Simple trapeziectomy has been shown to be as effective as more sophisticated techniques in some prospective randomized trials [16], but many hand surgeons find this simple resection arthroplasty relatively unappealing. I favor simple trapeziectomy for its simplicity, safety, and quicker recovery [16].

Potential Disease Complications

Hand osteoarthritis is a chronic, progressive disease that is a nuisance and not a danger. The only potential complications are associated with treatments.

Potential Treatment Complications

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. The newer nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors) have been associated with cardiovascular risks [17].

The primary risks associated with injections are infection and an allergic reaction to the medication used, but both are extremely rare. Some patients develop a hematoma or complain of substantial pain after an injection.

Potential surgical complications include wound infection, neuroma, and hematoma. The major source of dissatisfaction after surgery is persistent pain, and its sources are controversial.