CASE 32 Coronary Air Embolism

Cardiac catheterization

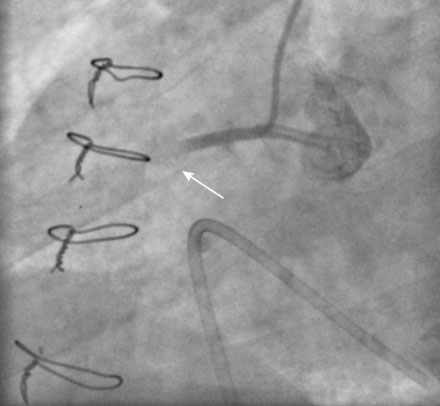

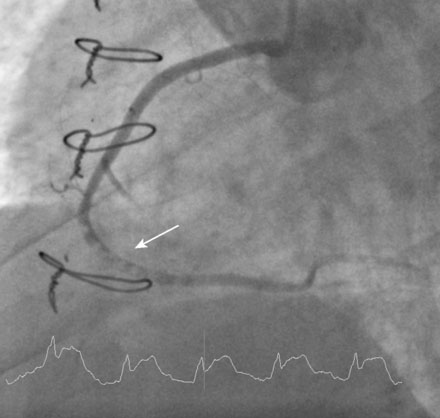

The operator first measured right heart pressures; these were found to be normal with a right atrial pressure of 3 mmHg and preserved cardiac output. The right coronary artery was engaged with a right Judkins 4.0 catheter and appeared angiographically normal (Figure 32-1 and Video 32-1). Using a left Judkins 4.0 catheter, the operator engaged and imaged the left coronary artery; this also appeared angiographically normal (Figure 32-2). At this point, the patient remained symptom-free. Endomyocardial biopsy was performed from the right femoral vein using a 7 French, 98 cm, 40-degree curved sheath positioned into the right ventricle. Three samples were obtained, and while the operator was attempting a fourth sample, the patient developed hypotension and sinus bradycardia. Marked inferior ST-segment elevation appeared on the monitor screen.

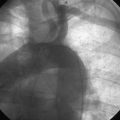

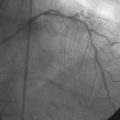

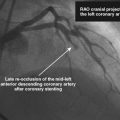

The operator engaged a 6 French right Judkins 4.0 guide catheter into the right coronary artery. Angiography demonstrated occlusion of the right coronary artery in the midportion of the vessel (Figure 32-3 and Video 32-2). Another angiogram performed a few minutes later clearly showed air bubbles within the coronary (Figure 32-4 and Video 32-3). She was placed on nasal oxygen at 6 L/min, and heparin (70 U/kg) was administered by intravenous bolus. The operator placed a 0.014 inch floppy-tipped guidewire into the distal artery and aspirated the air bubbles using an aspiration catheter, with resolution of ST-segment elevation and restoration of TIMI-3 flow (Video 32-4). The left coronary was reimaged and showed no abnormalities; similarly, left ventriculography revealed normal ventricular function. The patient was transferred to the coronary care unit for further management.

Discussion

Operators can prevent most cases by carefully aspirating catheters when performing exchanges and when connecting to the manifold. In the event that this complication occurs, several treatment options can be considered.1 Small amounts of air may be tolerated without symptoms or adverse sequelae and usually dissipate spontaneously by dissolving into the blood, requiring no further therapy. Large amounts of air causing adverse clinical consequences require treatment. In addition to aspiration with a simple catheter, as performed in this case, the administration of high concentration oxygen helps dissipate the air bubbles.