Valarie A. Pompey

DEFINITION AND INCIDENCE

Retching, an involuntary attempt to vomit, consists of rhythmic, labored spasmodic movement of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles causing regurgitation into the esophagus (Woodruff, 2004). Retching often follows nausea and precedes vomiting. Descriptors include “dry heaves.”

Vomiting, often confused with nausea, is the forceful contraction of the abdominal muscles (stomach), to cause the expulsion of stomach contents through the mouth (National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN], 2005). Common descriptors include “throwing up.”

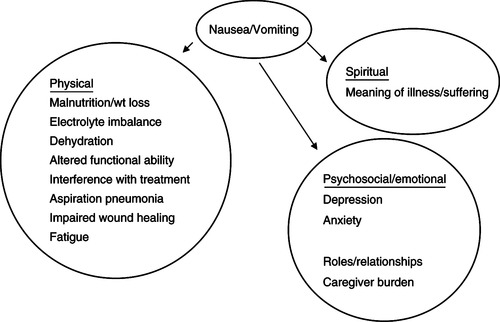

Nausea and vomiting (N/V) are two of the most frequently reported and feared side effects experienced by patients throughout their cancer experience. N/V affects 60% to 80% of cancer patients undergoing active treatment (Cunningham, 2005), 50% to 60% of patients with advanced disease (Herndon, Jackson, & Hallin, 2002), and as many as 40% of terminally ill patients within in their last week of life (Kazanowski, 2001). If untreated, complications can lead to unnecessary hospitalizations and diminished quality of life (Figure 31-1). N/V is particularly prevalent in persons with breast, stomach, and gynecological cancers, as well as persons with AIDS (Kazanowski, 2001). At end-of-life, N/V is commonly seen as a result of certain conditions such as bowel obstruction, hypercalcemia, constipation or impaction, use of opioids, uremia, and increased intracranial pressure secondary to metastatic disease in the brain. Effective management of these individual symptoms during initial and continued therapy profoundly influences symptom response throughout the cancer trajectory (Rhodes & McDaniel, 2001).

|

| Figure 31-1

Data from Woodruff, R. (2004). Nausea and vomiting. In Palliative medicine (4th ed., pp. 223-237). New York: Oxford University Press; and King, C.R. (2001). Nausea and vomiting. In B.R. Ferrell & N. Coyle (Eds.). Palliative nursing (pp. 107-121). New York: Oxford University Press.

Oxford University Press

|

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Still not well defined, the physiological mechanisms for N/V are complex and may involve one or more mechanisms and can occur from one or more neurotransmitters (Wickham, 2005). The vomiting center (VC), located in the brainstem along with the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), located in the area postrema of the fourth ventricle of the brain, coordinate the processes involved in N/V. The CTZ is stimulated by chemicals and neurotransmitters found in the cerebrospinal fluid and blood. The CTZ, the VC, and the gastrointestinal tract have many neurotransmitter receptors. Activation of these receptors by noxious stimuli results in the symptoms of N/V. The principal neuroreceptors involved in the emetic response include dopamine and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine 3 [5-HT 3]) receptors. Other receptors involved in signal transmission include acetylcholine, corticosteroid, histamine, cannabinoid, opiate, and neurokinin-1 (NK-1), which are located in the VC and vestibular center of the brain (NCCN, 2005) (Table 31-1).

| Receptors and Neurotransmitters | Trigger | Antiemetic Class |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal Tract | ||

| Serotonin (5-HT 3) |

Irritation

Gastric stasis

Hepatomegaly

Radiation therapy

Chemotherapy

Obstruction

|

Antihistamine

5-HT 3 antagonist

Anticholinergic

|

| Vestibular Apparatus | ||

|

Histamine (H 1)

Acetylcholine

|

Motion |

Antihistamine

Anticholinergic

|

| Chemoreceptor Trigger Zone | ||

|

Substance P

Dopamine (D 2)

Serotonin (5-HT 3)

|

Chemicals

Electrolyte imbalance

Drugs

|

NK-1 antagonist

Antidopaminergic

5-HT 3 antagonist

|

| Cortex | ||

| Pressure receptors |

Anxiety, stress

Raised intracranial pressure

Sights, smells, taste

|

|

| Vomiting Center | ||

|

Acetylcholine

Histamine receptor (H 1)

Serotonin (5-HT 2)

|

Gastrointestinal tract

Vestibular apparatus

Cortex

Chemoreceptor trigger zone

|

|

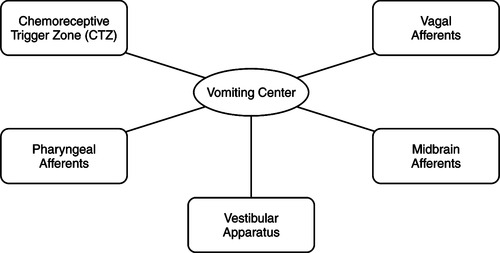

The VC is located in the lateral reticular formation of the medulla oblongata and is situated close to areas in the brain responsible for respiration, salivation, vasomotor processes, and vestibular apparatus (Ezzone, 2000). The VC, which coordinates the process of N/V, receives signals from the cerebral cortex and higher brainstem, thalamus, hypothalamus, and the vestibular system. It also receives emetic impulses via the vagus and splanchnic nerves from the pharynx and gastrointestinal tract when enterochromaffin cells in the upper gastrointestinal tract are stimulated (Figure 31-2). The VC also receives signals from the CTZ, which can initiate vomiting only via the VC (Mannix, 1999).

|

| Figure 31-2 |

Vomiting occurs when efferent impulses are sent from the VC to the salivation center, abdominal muscles, respiratory center, and cranial nerves. Box 31-1 lists common causes of N/V in the palliative care setting; the causes most frequently identified in persons with end-stage disease are identified by an asterisk.

Box 31-1

GASTROINTESTINAL

Gastrointestinal obstruction*

Constipation*

Gastritis*

Gastric stasis*

Squashed stomach syndrome

Gastrointestinal infection

Carcinomatosis

Extensive liver metastasis

PHARYNGEAL IRRITATION

Candida spp. infection

Thick sputum

Cough

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

Increased intracranial pressure*

Posterior fossa tumors or bleeding

Meningitis, infectious or neoplastic

MEDICATIONS

Opioids*

Antibiotics

Chemotherapy

Corticosteroids

Digoxin

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Iron

PSYCHOLOGICAL AND EMOTIONAL

Anxiety

Pain

Conditioned response (anticipatory nausea)

SITUATIONAL

Odors

Inadequate mouth care

ASSESSMENT AND MEASUREMENT

Identification of the possible cause(s) of N/V begins with a detailed history and physical examination. In patients with advanced cancer, N/V is frequently due to multiple causes (Woodruff, 2004). Questions about onset, precipitating and aggravating factors, quality (duration, frequency, and severity), and relieving factors should be documented so that an individualized approach to management can be implemented. Assessment of the gastrointestinal status, that is, abdominal distention, presence of bowel sounds, and presence of other associated symptoms such as constipation, should be part of the total process. It is also very important to remember that the most reliable way to assess nausea is through the patient’s report.

Temporal Characteristics

▪ Onset: When did it start?

▪ Pattern: Specific times of the day? Continuous or intermittent?

If it is intermittent, what are the frequency and length of episodes?

Does nausea precede vomiting, or does vomiting come without warning?

▪ Relieving and aggravating factors: What makes it better or worse?

Affected by movement?

Better or worse with eating?

In certain situations?

With certain smells?

Risk Factors

Disease Related

▪ Primary or metastatic tumor of the central nervous system that includes the VC or increased intracranial pressure

▪ Obstruction of a portion of the gastrointestinal tract

▪ Food toxins, infection, or motion sickness

▪ Metabolic abnormalities, such as hyperglycemia, hyponatremia, hypercalcemia, and renal or hepatic dysfunction

▪ Advanced stomach and breast cancers, any cancer at end-stage

▪ Pharyngeal irritation from tenacious sputum, candidiasis

▪ Hepatomegaly

Treatment Related

▪ Stimulation of receptors of the labyrinth of the inner ear

▪ Obstruction, irritation, inflammation, and delayed gastric emptying stimulating the gastrointestinal tract through the vagal visceral afferent pathway

▪ Stimulation of the VC through cellular by-products associated with cancer treatments. Chemotherapy drugs are classified by their potential to cause chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) within the first 24 hours of drug administration. N/V occurring within the first 24 hours of chemotherapy drug administration is called acute. N/V that persists for several hours or days 24 hours or more after treatment is termed delayed. Anticipatory N/V can develop depending on how successful prior experiences at control have been and is usually triggered by cues linked to prior treatments such as smells, sounds, etc.

▪ Stimulation of the VC through afferent pathways from radiation therapy of the gastrointestinal tract. Radiation-induced nausea and vomiting (RINV) depends on the site of treatment, size of treatment field, and radiation dose. Patients at highest risk have received a large volume of radiation to the upper abdominal tissues. Time to onset of radiation is related to the dose fraction: 10 to 15 minutes after total body irradiation or hemibody irradiation to as much as 1 to 2 hours after smaller doses of radiation to a specific site (i.e., upper abdomen). RINV may persist for several hours (Wickham, 2005).

▪ Side effects of medications such as digitalis, morphine, antibiotics, iron, vitamins, and chemotherapy agents. Emetogenicity of various chemotherapy agents is given in Box 31-2.

Box 31-2

Oncology Education Services (OES)

CHEMOTHERAPY

Emetic Risk of Chemotherapy (Generic Names)

High (>90%)

Carmustine (>250 mg/m 2)

Cisplatin (>50 mg/m 2)

Cyclophosphamide (>1500 mg/m 2)

Dacarbazine (>500 mg/m 2)

Mechlorethamine

Procarbazine (orally)

Streptozocin

Moderate (30% to 90%)

Aldesleukin (IL-2)

Cyclophosphamide (<1500 mg/m 2)

Carmustine (<250 mg/m 2)

Doxorubicin

Cisplatin (<50 mg/m 2)

Epirubicin

Cytarabine (>1 g/m 2)

Idarubicin

Irinotecan

Ifosfamide

Melphalan (<50 mg/m 2)

Methotrexate (250 to 1000 mg/m 2)

Carboplatin

Cyclophosphamide (orally)

Low (10% to 30%)

Doxorubicin (liposomal)

5-Fluorouracil

Mitoxantrone (<12 mg/m 2)

Gemcitabine

Temozolomide

Mitomycin

Etoposide (orally)

Paclitaxel

Cytarabine (100-200 mg/m 2)

Topotecan

Docetaxel

Trastuzumab

Minimal (<10%)

Asparaginase

Methotrexate (<50 mg/m 2)

Bleomycin

Capecitabine

Rituximab

Bevacizumab

Vincristine

Vinblastine

Vinorelbine (intravenously)

RADIATION THERAPY

| Low Risk (0 to 10%) | Moderate Risk (10% to 55%) | High Risk (55% to 90%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Head and neck

Extremities

|

Hemibody to lower body

Thorax

Pelvis

|

Total body irradiation

Hemibody to upper body

Entire abdomen

Upper abdomen

|

SURGERY POSTANESTHESIA

| Low Risk (0 to 10%) | Moderate Risk (10% to 55%) | High Risk (55% to 90%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Craniotomy

Laparotomy

|

Ear, nose, throat

Laparoscopy

|

Major breast surgery

Strabismus surgery

|

Data from Wickham, R. (2005). Nausea and vomiting: Palliative care issues across the cancer experience. Oncol Support Care Q, 1(4), 44-57; and Cunningham, R.S. (2005). Using clinical practice guidelines to improve clinical outcomes in patients receiving emetogenic chemotherapy. Oncol Support Care Q, 3(1), 4-10. Pittsburgh: Oncology Education Services (OES).

▪ Side effects of concentrated nutritional supplements

▪ Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is related to the anesthesia rather than the surgical procedure itself. PONV is more likely to occur after certain surgeries, such as craniotomy, laparotomy, and major breast surgery. N/V potentiates patient discomfort and increases the risk for postoperative complications, such as wound dehiscence, bleeding, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalance (Wickham, 2005).

Patient Related

▪ Previous experience with N/V

▪ Alcohol use (chronic or heavy drinkers experience less N/V than do nondrinkers).

▪ Gender: Women are at greater risk for CINV, PONV, and N/V from other causes.

Situational

▪ Increased levels of tension, stress, emotions, and anxiety

▪ Noxious odors or visual stimuli

▪ Conditioned (anticipatory) responses to previous cancer and other stressful experiences. History of motion sickness increases risk. This occurs in 25% of chemotherapy patients.

Treatment Options

Ask what has been tried to treat the nausea.

▪ Pharmacological interventions, including prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, and home, herbal, and natural remedies

▪ Nonpharmacological interventions such as alternative and complementary therapies

Additional symptoms (sequelae) (Berendt, 1998; Griffie & McKinnon, 2002) should be sought.

▪ Change in bowel pattern? Have bowels moved in the last 24 hours? When was the last bowel movement?

▪ What medications have been tried in the last 24 hours?

▪ What other medications have been tried for this episode of the nausea?

▪ What does the patient feel is the cause of the nausea?

▪ What is the content of the vomitus: food, bile, presence of blood or feces?

▪ What is the volume of the emesis (large volume suggests gastric stasis)?

▪ Heartburn or reflux symptoms?

▪ What are the patient goals for comfort?

▪ Are there any associated symptoms such as anxiety, pain, odynophagia or dysphagia, or cough that may require simultaneous intervention?

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Physical examination is considered an essential and complementary element to collection of the patient’s history during the assessment process. Often, information gathered from the physical examination helps determine the cause of N/V and guides the practitioner in selecting the appropriate treatment.

▪ Conduct a general physical examination (Berendt, 1998; Griffie & McKinnon, 2002).

Note any recent weight change.

Check for fever to rule out infection.

Assess for signs of dehydration.

Assess intake versus output.

Assess mental status changes and orientation or level of consciousness.

Conduct a psychosocial assessment: Explore anxiety-producing events and coping abilities.

Fundi of eyes should be examined for papilledema if cerebral metastasis is suspected, although increased intracranial pressure should not be excluded in its absence.

Cardiovascular status (pulse, tachycardia; blood pressure, check for postural hypotension) should be determined.

Abdomen should be checked for ascites, hepatomegaly, abdominal distention, tenderness or pain, masses, and presence and character of bowel sounds.

Rectal examination should be conducted for tenderness, constipation, impaction, and masses, and a stool examination should be conducted for occult blood.

Skin assessment should be performed for jaundice, uremic frost, pruritus, and turgor.

▪ Consider medical diagnosis, especially disease processes with a potential to cause N/V, such as gastrointestinal or genitourinary malignancies, primary or metastatic brain tumors, liver failure, and renal failure.

Bowel obstruction is relatively common in patients with abdominal tumors, especially those with colorectal and ovarian cancers.

Increased intracranial pressure is usually due to primary or secondary brain tumors or metastasis and/or to accompanying cerebral edema.

Uremia is usually caused by primary or secondary breast or bladder tumors (C. Poe, 2005, personal communication).

Determine treatment history: Is the patient undergoing active treatment with chemotherapy or radiation therapy? Has there been recent or past treatment with chemotherapy or radiation?

Review the surgical history. Have there been any recent gastrointestinal surgeries or procedures?

Review current medications that may contribute to nausea (e.g., opioids, steroids, digoxin).

Evaluate the patient’s past experiences with N/V and the effectiveness of interventions used in prior experiences.

Investigate other possible etiologies such as uncontrolled pain, pancreatic disease, psychological distress, gastric irritation, hypercalcemia, or acute gastrointestinal infection unrelated to the disease (C. Poe, 2005, personal communication).

DIAGNOSTICS

The following tests may be necessary and appropriate if other forms of assessment fail to identify the cause(s) of N/V (Campbell & Hately, 2000). Possible causes include disease recurrence or progression, central nervous system metastases, abdominal abnormalities, infection, metabolic abnormalities, and obstruction by tumor or stool.

▪ Laboratory studies

Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine

Ionized calcium

Liver function tests

Serum drug levels

Complete blood cell count with differential

Serum sodium to identify dehydration

Computed tomography scanning

Magnetic resonance imaging

Abdominal flat plate

Endoscopy

INTERVENTION AND TREATMENT

Interventions to eliminate causes of N/V are the first step to its management (Gullatte, Kaplow, & Heidrich, 2005). When that is not possible, antiemetics are the mainstay to management of N/V in any setting. Understanding the underlying cause and using an individualized approach to care are key in selecting the most appropriate agent for successful management. Nurses working in palliative care have the challenge of providing care to patients with several comorbidities, resulting in multiple symptoms requiring simultaneous intervention (Campbell & Hately, 2000). Because of this unique challenge, multiple drugs in conjunction with nonpharmacological approaches and utilization of the interdisciplinary team may be needed to control symptoms. Successful management of N/V with multifactorial causes is dependent on the following (Campbell & Hately, 2000; King, 2001):

▪ Assessment

▪ Accurate diagnosis and identification of cause(s) and identification of emetic pathway

▪ Choice of the correct antiemetic

▪ Choice of the most efficacious route that ensures delivery of the antiemetic to the site of action

▪ Effective titration of dose and regular administration of the antiemetic

▪ Treatment of reversible causes

▪ Change to and adjustment of the protocol if it is not working

▪ Appropriate adjuvant medications and nonpharmacological interventions

▪ Individualized and holistic nursing care (remember that anxiety or psychological stress can cause nausea)

▪ Consideration and evaluation of the potential adverse or opposing effects of drug(s) used to treat N/V

Pharmacological Interventions

Antiemetics are considered the drug of choice, yet they often prove to be ineffective when used alone. This is most likely due to inadequate dose, incomplete diagnosis, or incorrect diagnosis. If the cause is multifactorial, select the most potent antiemetic for the probable cause, rather than one multipurpose agent. Most palliative care programs have available a compounding pharmacist who can prepare a combination of antiemetics in convenient vehicles for administration, such as suppository, oral suspension, topical, or transdermal forms. Common combinations in the palliative setting include the following (Griffie & McKinnon, 2002):

▪ Diphenhydramine, dexamethasone, and metoclopramide

▪ Diphenhydramine, lorazepam, and haloperidol

▪ Haloperidol, lorazepam, metoclopramide, and diphenhydramine

Table 31-2 outlines medications used to treat nausea and vomiting in the palliative care setting.

| Specific Medication | Recommended Dosing Schedule |

|---|---|

| Dopamine Antagonists | |

| Prochlorperazine (Compazine) | Orally, intravenously, intramuscularly 10 mg every 6 hr; per rectum 25-mg suppository every 12 hr |

| Chlorpromazine (Thorazine) | Orally, intravenously, intramuscularly 25 to 50 mg every 6 hr; per rectum 25-mg suppository every 6 hr |

| Haloperidol (Haldol) | Orally, intravenously, subcutaneously, intramuscularly 0.5 to 2 mg every 6 hr |

| Thiethylperazine (Torcan) | Intravenously, orally 10 mg every 8 hr |

| Promethazine (Phenergan) | Intravenously, orally 25 mg every 6 hr; per rectum 12.5- to 50-mg suppository every 6 hr |

| Metoclopramide HCl (Reglan) | Orally 10 mg ½ hr before meals and at bedtime |

| Serotonin Antagonists | |

| Ondanstron (Zofran) | Intravenously 32 mg or orally 24 mg prior to treatment; orally 4 to 8 mg every 8 hr |

| Granisetron (Kytril) | Intravenously or orally 1 to 2 mg daily |

| Dolasetron mesylate (Anzemet) | Intravenously or orally 100 mg intravenously or orally daily |

| Palonosetron (Aloxi) | Intravenously 0.25 mg 30 min before chemotherapy. |

| Prokinetic Drugs | |

| Metoclopramide HCl (Reglan) | Orally 10 mg ½ hr before meals and at bedtime |

| Corticosteroids | |

| Dexamethasone (Decadron) | Dose and schedule are empiric; orally or intravenously 4 to 10 mg every 6 hr |

| Benzodiazepines | |

| Lorazepam (Ativan) | Orally or intravenously 0.5 to 2.0 mg every 6 hr |

| Cannabinoids | |

| Dronabinol (Marinol) | Orally 2.5 to 10 mg every 6 hr |

| Antihistamines | |

| Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) | Orally or intravenously 25 to 50 mg every 6 hr |

| Hydroxyzine (Vistaril) | Orally or intramuscularly 25 to 50 mg every 6 hr |

| Antisecretory Agents | |

| Octreotide acetate (Sandostatin) | Subcutaneously 100 to 600 mcg/24 hr; used in intestinal obstruction to reduce gastrointestinal secretions and motility |

| Substance P/Neurokinin-1 Antagonist | |

| Aprepitant (Emend) | Orally 125 mg day 1, 80 mg days 2 and 3, day 1 at 1 hr before chemotherapy, days 2 and 3 in morning |

| Scopolamine hydrobromide (Transderm-Scop) | 1.5-mg patch every 72 hr |

Nonpharmacological Interventions

Use of the interdisciplinary team for management of symptoms is unique to palliative care. Psychological interventions to control physiological responses (King, 2001) are a common and quite successful approach in the palliative care setting. The intent of these interventions is to focus attention on other stimuli rather than on the symptoms of N/V. Most interventions are based on behavioral therapies such as relaxation techniques, guided imagery, distraction, systemic desensitization, massage and music therapy, self-hypnosis, acupuncture, acupressure, and biofeedback (Ezzone, 2000; King, 2001). Patient and family involvement is the mainstay of successful symptom management. Box 31-3 outlines some self-care activities that patients and their caregivers can implement independently and as an adjunct to nursing interventions to control N/V.

Box 31-3

Oral care should be provided after each episode of nausea and vomiting.

Apply cool, damp cloth to forehead, neck, and wrists.

Decrease noxious stimuli like odors and pain.

Restrict fluids with meals.

Eat frequent small meals.

Eat bland, cool, or room-temperature food.

Provide clear liquids, Popsicles, and/or Gatorade for 24 hours following acute nausea and vomiting episodes.

Have patient wear loose-fitting clothes.

Provide fresh air with fan, open windows.

Have patient avoid sweet, salty, fatty, and spicy foods.

Limit sounds, sights, and smells that precipitate nausea and vomiting.

Patient should avoid moving and reclining for 30 min after eating.

Data from King, C.R. (2001). Nausea and vomiting. In B.R. Ferrell & N. Coyle (Eds.). Palliative nursing (pp. 107-121). New York: Oxford University Press; and Rhodes, V. & McDaniel, R. (2001). Nausea, vomiting and retching: Complex problems in palliative care. CA Cancer J Clin, 51(4), 232-248.

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

Working closely with patients and their caregivers to prevent the causes of N/V or to aggressively managing existing symptoms requires teaching patients and/or families interventions for independent management. If those interventions do not prove successful, the importance of prompt notification of the clinician regarding refractory symptoms is paramount to prevent complications. Educational materials on disease states, effects of cancer treatment, and written information on how to manage side effects are invaluable resources to refer to when away from the clinical setting. Reliable and consistent information is important to assist patients in coping with the cancer treatment process (Berendt, 1998; Ezzone, 2000; Griffie & McKinnon, 2002).

▪ Encourage use of self-care diaries and logs to record the frequency of N/V.

▪ Instruct patient to notify clinician when

More than three episodes of vomiting occur in a day or 2 consecutive days of vomiting.

Vomiting occurs soon after oral administration of antiemetics.

Fever develops.

There is increased or escalating pain or weakness.

There are signs and symptoms of dehydration and aspiration.

There is weight loss.

▪ Instruct patient about correct dose and administration of medication.

▪ Teach patient to avoid eating or drinking for 1 to 2 hours after vomiting and encourage fluid intake. Clear liquid diet for 24 hours may allow the gastrointestinal tract to rest and give the antiemetics time to work.

▪ Instruct patients and caregivers that the patient should be allowed to eat when and what he or she chooses.

▪ Suggest that eating smaller meals throughout the day is more tolerable.

▪ Provide effective management of symptoms such as pain, anxiety, and cough to prevent breakthrough nausea.

▪ Suggest environmental modification—cool, well-ventilated, lowered lighting and noise levels, and absence of noxious sights and smells.

▪ Teach nonpharmacological relaxation and distraction activities.

▪ Inform patient that treatment of any symptom including N/V is a patient choice; instruct patient about consequences of no treatment as part of overall goal setting when developing a plan of care.

▪ Instruct on positioning techniques to decrease risk of aspiration.

EVALUATION AND FOLLOW-UP

Effective management of any symptom involves the evaluation of patient response to mutually identified goals through routine follow-up. As with pain, when there is a new intervention initiated or dose change, patient contact should occur within 24 hours. In the home care setting, if a return visit is not feasible, a skilled clinician can accomplish this follow-up with a telephone call followed by face-to-face contact as soon as possible.

Mr. B. is a 78-year-old man who has advanced prostate cancer. He enters the clinic for control of nausea. He has been under treatment for the past 7 years and now has uncontrolled disease with widespread metastatic sites of cancer, including the bladder. He has nephrostomy tubes in place. Three months ago, he underwent a colostomy for blockage of his lower bowel. Mr. B. is receiving leuprolide acetate injections every 3 months. He has not had radiation therapy in the past year. He reports a weight loss of 30 pounds over the last 4 months. When asked what the physicians told him about his disease status, he states, “They told me 6 to 9 months, 6 months ago.”

The clinician obtains the following assessment data regarding Mr. B.’s nausea: The nausea is constant and began after the colostomy was placed. It has gradually increased in intensity and now has accompanying episodes of emesis, about every third day. His emesis consists of small amounts of digested food. He reports that eating large amounts of food makes it worse. He cannot name anything that he has tried that makes it worse or makes it better. The colostomy is functioning. Bowel sounds are normal and laboratory values are normal.

In determining the best pharmacological choices, the clinician considers that the nausea is constant, the cause is not known, and there are no signs or symptoms of intestinal obstruction. A dopamine antagonist is perhaps the best beginning point to provide broadest coverage of possible causes. Prochlorperazine, 10 mg orally every 6 hours around the clock, is an appropriate starting regimen.

This patient will likely benefit from nonpharmacological interventions as well. Suggest small meals. Assure Mr. B. that there are a number of approaches to therapy and that any medications are easily adjusted to find the best medication and dose for him. Allow time for Mr. B. to talk about his statement, “They told me 6 to 9 months, 6 months ago,” as this may open a wide variety of emotional concerns that need to be addressed.

Mr. B. and his family are given the following instructions:

▪ Start the prochlorperazine, 10 mg orally every 6 hours around the clock.

▪ Keep a record of episodes of nausea and emesis and note any relationship to time of last meal.

▪ Contact clinician if no relief in intensity of nausea occurs in 3 days (mutually agreed-upon goal).

REFERENCES

Berendt, M.C., Alterations in nutrition: Nausea and vomiting, In: (Editors: Itano, J.K.; Taoka, K.N.) Core curriculum for oncology nursing ( 1998)Oncology Nursing Society, Pittsburgh, pp. 238–243.

Campbell, T.; Hately, J., The management of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer, Int J Palliat Nurs 6 (1) ( 2000) 18–25.

Cunningham, R.S., Using clinical practice guidelines to improve clinical outcomes in patients receiving emetogenic chemotherapy, Oncol Support Care Q 3 (1) ( 2005) 4–10; Pittsburgh: Oncology Education Services (OES)..

Ezzone, S.A., Nausea and vomiting, In: (Editors: Nevidjon, B.M.; Sowers, K.W.) A nurse’s guide to cancer care ( 2000)Lippincott, Philadelphia, pp. 295–310.

Griffie, J.; McKinnon, S., Nausea and vomiting, In: (Editors: Kuebler, K.K.; Berry, P.; Heidrich, D.E.) End of life care: Clinical practice guidelines ( 2002)Saunders, Philadelphia, pp. 333–343.

Gullatte, M.M.; Kaplow, R.; Heidrich, D.E., Nausea and vomiting, In: (Editors: Kuebler, K.K.; Davis, M.P.; Moore, C.D.) Palliative practices: An interdisciplinary approach ( 2005)Elsevier/Mosby, St. Louis, pp. 229–231.

Herndon, C.M.; Jackson, K.C.; Hallin, P.A., Management of opioid-induced gastrointestinal effects in patients receiving palliative care, Pharmacotherapy 22 (2) ( 2002) 240–250.

Kazanowski, M.K., Nausea and vomiting near end of life, In: (Editors: Matzo, M.L.; Sherman, D.W.) Palliat care nursing ( 2001)Springer, New York, pp. 340–342.

King, C.R., Nausea and vomiting, In: (Editors: Ferrell, B.R.; Coyle, N.) Palliative nursing ( 2001)Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 107–121.

Mannix, K.A., Palliation of nausea and vomiting, In: (Editors: Doyle, D.; Hanks, G.; MacDonald, N.) Oxford textbook of palliative medicine2nd ed. ( 1999)Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 489–498.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Antiemesis guidelines. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Retrieved from www.nccn.org ( 2005).

Rhodes, V.; McDaniel, R., Nausea vomiting and retching: Complex problems in palliative care, CA Cancer J Clin 51 (4) ( 2001) 232–248.

Wickham, R., Nausea and vomiting: Palliative care issues across the cancer experience, Oncol Support Care Q 1 (4) ( 2005) 44–57.

Woodruff, R., Nausea and vomiting, In: Palliative medicine4th ed. ( 2004)Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 223–237.