CHAPTER 31

Flexor Tendon Injuries

Definition

The flexor tendons of the hand are vulnerable to laceration and rupture. These injuries are most commonly seen in individuals who work around moving equipment, use knives, or wash glass dishes; in people with rheumatoid arthritis; and in athletes (jersey finger) [1]. The flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) of the ring finger is the most commonly involved [2]. Incomplete injuries to the flexor tendon are easily missed on physical examination and can progress to full ruptures.

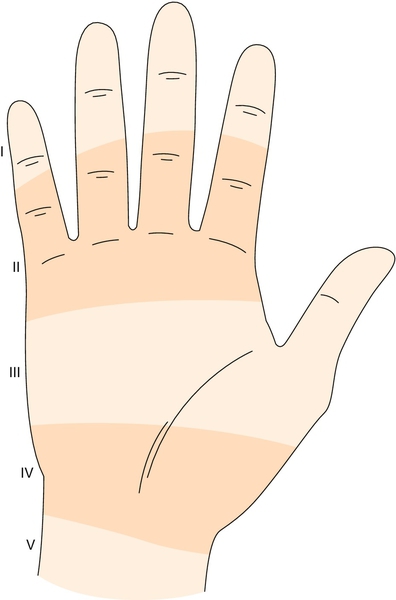

Regions of potential tendon injury are divided into five zones (Fig. 31.1) [3]. Zone I is from the tendon insertion at the base of the distal phalanx to the midportion of the middle phalanx. Laceration or injury in this zone results in disruption of the FDP tendon and the inability to flex the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. Zone II extends from the midportion of the middle phalanx to the distal palmar crease. This zone is known as no man’s land because of the poor functional results after tendon repair [4,5]. Tendon injury in this zone usually involves both FDP and flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) tendons and results in inability to flex the DIP and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints. Zone III is located from the distal palmar crease to the distal portion of the transverse carpal ligament. This zone includes the intrinsic hand muscles and vascular arches. Zone IV overlies the transverse carpal ligament in the area of the carpal tunnel. In this zone, injuries usually involve multiple FDP and FDS tendons. Zone V extends from the wrist crease to the level of the musculotendinous junction of the flexor tendons. Injuries in this region most often result from self-inflicted laceration (suicide attempts).

The flexor tendons are held close to the bone in zone I and zone II by a complex series of pulleys and vincula. These structures are frequently injured with the tendons [1].

Symptoms

On occasion, individuals may hear a popping sensation as the flexor tendon tears. This is followed by pain, swelling, and inability to flex the affected joint. Sensation of the involved finger is often affected because of the proximity of the flexor tendons to the neurovascular bundle.

Physical Examination

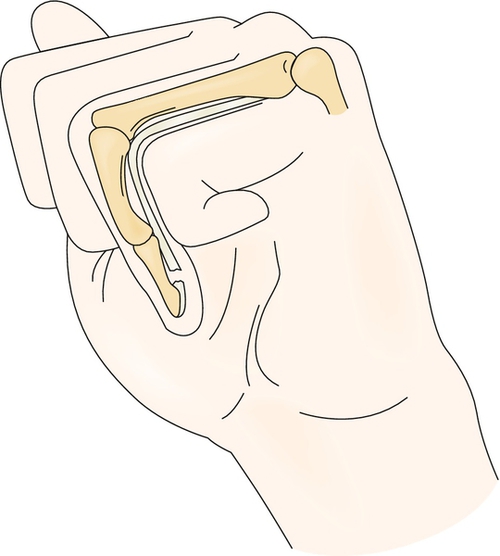

Obtaining a detailed history is important to outline the mechanism of injury. Evaluation begins with observation of the resting hand position. If the flexor tendon is completely severed, the unsupported finger will assume an extended position (Fig. 31.2) [1,6]. Active flexion of all finger joints needs to be assessed. If active finger flexion is not observed because of pain, tenodesis can be employed to determine whether the tendon is intact. The wrist is passively extended, and all fingers should assume a relatively flexed posture. If the flexor tendons are disrupted, the finger will remain in a relatively extended posture.

Flexion strength of each digit should be evaluated by manual muscle testing or finger dynamometry. Strength is evaluated by having the patient individually flex first the DIP joint and then the PIP joint against applied resistance. It is possible to have a complete laceration of the flexor tendons with preservation of peritendinous structures and active motion. In these cases, however, flexion will be weak [7].

For individual function of the FDP tendon to be checked, the patient is asked to flex the fingertip at the DIP joint while the PIP joint is maintained in extension. If there is injury to the FDP tendon, the patient will be unable to flex the DIP joint.

It is difficult to diagnose solitary injuries of the FDS tendon because of the FDP tendon’s ability to perform flexion of all finger joints through intertendinous connections. For the integrity of the FDS tendon to be isolated, all the fingers are held straight, placing the FDP tendon in a biomechanically disadvantaged position. The patient actively attempts to flex the finger to be tested while the other fingers are held in relative extension. If the patient is unable to move the finger, injury most likely has occurred to the FDS tendon. This test is reliable only for the middle, ring, and small fingers.

Sensation of the finger should be evaluated because open tendon injuries often are accompanied by injuries of the nearby digital nerves. Two-point discrimination of radial and ulnar aspects of the digit should be assessed before injection of local anesthetic for wound care [1].

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations include difficulty with power grasp if the ulnarly sided tendons are involved and precision grasp problems if the radially sided tendons are involved. The patient may present with inability to button shirts, to pinch small objects, or to firmly grasp objects.

Diagnostic Studies

Radiographic evaluation includes anteroposterior and lateral views of the involved fingers. These assist in identification of joint dislocation, articular disruption, avulsion, long bone fractures, and potential for retained foreign bodies. Ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging are used to identify partially lacerated or ruptured tendons. Ultrasound provides dynamic studies of the tendons.

Treatment

Initial

Surgical intervention is almost always required for flexor tendon injuries [1,7]. Protection of the affected finger in a bulky dressing and meticulous wound care are recommended before surgical correction.

Cleaning and repair of superficial wounds should be performed if surgical referral is delayed. Optimally, surgical correction of the flexor tendon injury occurs within the first 12 to 24 hours. Delayed primary repair is performed in the first 10 days. If primary repair is not performed because of infection, secondary repair can be performed up to 4 weeks. If repair is not performed within 4 weeks, the tendon usually is retracted within the sheath, making surgical repair difficult [7].

Newer surgical repair and suture techniques have improved the strength of repaired flexor tendons, providing for earlier rehabilitation [7–9].

Rehabilitation

Postoperative rehabilitation of repaired tendons has changed greatly in the past three decades through initiation of early protected motion [10–14]. Historically, the repaired fingers were placed in an immobilization splint for up to 2 months. This often led to adhesion formation and ultimately the loss of motion and function [12].

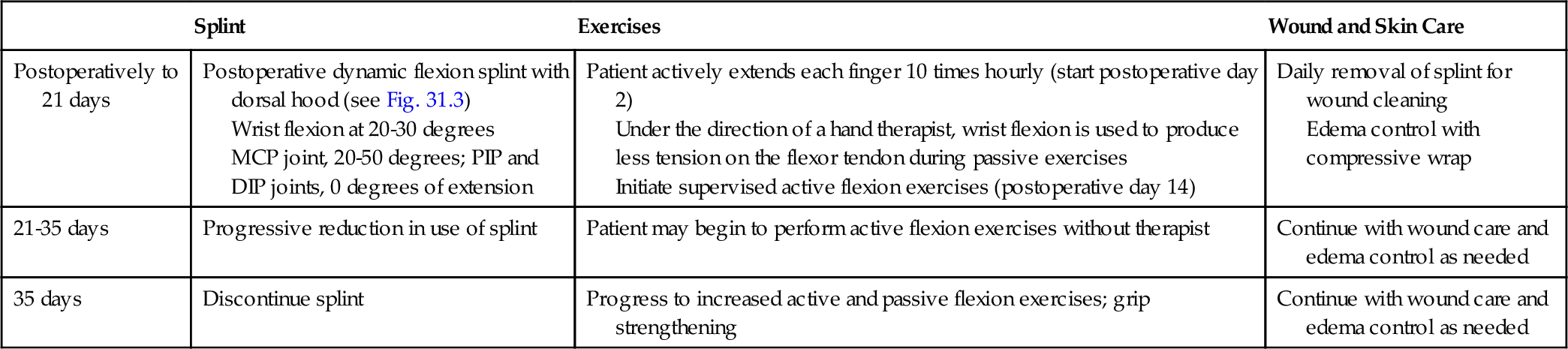

The currently accepted rehabilitation schemes for repaired flexor tendons are essentially the same for all zones (Table 31.1).

Table 31.1

Flexor Tendon Injuries (Immediate Motion)

| Splint | Exercises | Wound and Skin Care | |

| Postoperatively to 21 days | Postoperative dynamic flexion splint with dorsal hood (see Fig. 31.3) Wrist flexion at 20-30 degrees MCP joint, 20-50 degrees; PIP and DIP joints, 0 degrees of extension |

Patient actively extends each finger 10 times hourly (start postoperative day 2) Under the direction of a hand therapist, wrist flexion is used to produce less tension on the flexor tendon during passive exercises Initiate supervised active flexion exercises (postoperative day 14) |

Daily removal of splint for wound cleaning Edema control with compressive wrap |

| 21-35 days | Progressive reduction in use of splint | Patient may begin to perform active flexion exercises without therapist | Continue with wound care and edema control as needed |

| 35 days | Discontinue splint | Progress to increased active and passive flexion exercises; grip strengthening | Continue with wound care and edema control as needed |

Modified from Evans R. Early active motion after flexor tendon repair. In Berger RA, Weiss APC, eds. Hand Surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2003:710-735; Groth GN. Current practice patterns of flexor tendon rehabilitation. J Hand Ther 2005;18:169-174; and Evans R. Managing the injured tendon: current concepts. J Hand Ther 2012;25:173-189.

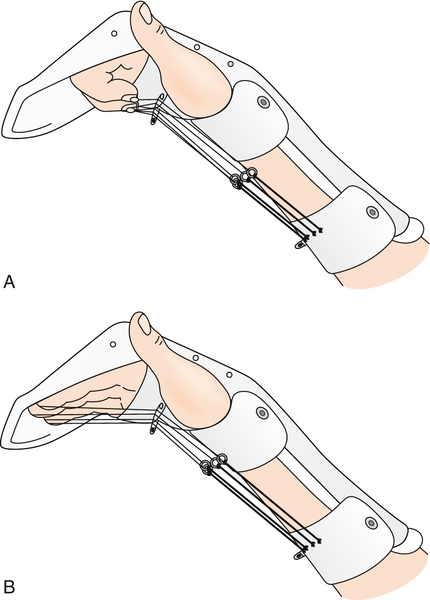

Immediately postoperatively, the hand is placed in a protective dorsal splint with 20 to 30 degrees of wrist flexion. All metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints are placed in 20 to 50 degrees of flexion, depending on zone [13–15]. A dorsal hood extends to the fingertip level, allowing PIP joint and DIP joint extension to 0 degrees. All of the fingers are held in flexion by dynamic traction applied by rubber bands originating from the proximal forearm with a pulley at the palm and attachment to the fingernails (Fig. 31.3A).

The patient is typically seen by the therapist 24 to 48 hours after surgical repair. Dressings are changed, edema control measures are initiated, and rehabilitation goals are discussed [12–14]. The patient is instructed to actively extend the fingers against the rubber band traction to the dorsal block, 10 repetitions hourly, to prevent flexion contractures (see Fig. 31.3B). The rubber band traction passively returns the fingers to a flexed position. At night, the traction is removed and the fingers are strapped to the dorsal hood with the PIP and DIP joints in extension.

The rehabilitation program may involve immediate short arc motion [12,13,16,17]. Under the supervision of a skilled therapist, the injured digit is placed in moderate flexion with the wrist in 30 to 40 degrees of extension, the MCP joints in 80 degrees of flexion, the PIP joints in 75 degrees of flexion, and the DIP joints in 30 to 40 degrees of flexion. The patient is then instructed to actively hold this position for 10 seconds. On completion of the static contraction, the therapist passively flexes the wrist. This allows natural tenodesis to extend the fingers. At day 21, the patient can initiate unsupervised active flexion exercises. At 35 days, the dorsal digital splint is removed and active tendon gliding exercises are initiated [12,14,15,17,18].

Modalities such as ultrasound, contrast or paraffin baths, whirlpool, and fluidized therapy may be used to promote wound healing and range of motion in the latter stages of therapy.

Procedures

Procedures are generally not indicated in flexor tendon injuries. Wound care is paramount to prevent infections of surgical incisions. Corticosteroid injections can be performed if stenosing tenosynovitis (triggering) develops at the flexor pulleys.

Surgery

Optimally, repair of the flexion tendon should occur within the first 48 hours after injury. Improper handling of tissues during repair can result in hematoma, damage to the pulley integrity, and damage to the vincula—the vascular supply of the tendons [19].

Potential Disease Complications

Injury to the flexor tendon mechanism can result in permanent loss of finger flexion. Partial tendon damage can easily be missed and result in either weakness or complete rupture.

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Postsurgical complications include adhesion formation and tendon rupture. Postsurgical tendon rupture is usually the result of aggressive motion, by either the patient or therapist, that results in failure of the repair. Reoperation is often required, which results in the greater propensity for adhesion formation. Adhesion formation and the loss of motion and strength complicate surgical repair, particularly in zone II [4,5].

Many other factors affect healing of the tendon and postoperative rehabilitation. Factors such as advanced age, poor circulation, tobacco and caffeine use, and generalized poor health can contribute to impaired healing. Scar formation can result in adhesion formation and decreased movement. Poor motivation and compliance with the therapy program result in less than optimal recovery.