CHAPTER 30. LYMPHEDEMA

Jane M. Armer and Sheila H. Ridner

Although it is hoped that lymphedema may decrease in incidence due to improved surgical techniques and procedures, lymphedema still occurs in a significant percentage of individuals and may be of sufficient degree to increase patient’s risk for infection, affect mobility, and cause a decline in overall quality of life (Muscari, 2004). It is important for the advanced practice nurse (APN) and all other palliative care health professionals to understand how to manage a patient with lymphedema.

DEFINITION AND INCIDENCE

Lymphedema is a condition in which excessive fluid and protein accumulate in the extravascular and interstitial space. This occurs when the lymphatic system cannot either accept or transport lymph (the colorless fluid that bathes the cells of the body, carrying away byproducts of metabolism and helping to fight infection) into the circulatory system (Browse, Burnand, & Mortimer, 2003; Rockson, 2001). Primary lymphedema due to genetic and familial abnormalities in the lymphatic structure or function may occur in 1 of every 10,000 individuals (Townsend, Beauchamp, Evers et al., 2001). Incidence of secondary lymphedema varies depending on the cause. For example, 15% to 20% of breast cancer survivors in the United States may develop lymphedema, and approximately 90 million individuals worldwide may have secondary lymphedema caused by filarial (parasitic) infections (Petrek, Pressman, & Smith, 2000; Townsend et al., 2001). Although the occurrence of lymphedema in palliative care settings is unknown, one lymphedema clinic reported that approximately 30% of their clients were advanced cancer patients with lower limb swelling (Logan, 1995), and lymphedema is cited in the literature as a distressful symptom experienced by patients in palliative care settings (Winn & Dentino, 2004).

Lymphedema is a chronic medical condition requiring careful management. Because lymphedema can develop at any time throughout life (Browse et al., 2003; Foldi, Foldi, & Kubik, 2003), the clinician may have to address both recent-onset (acute) and long-existing (chronic) lymphedema in patients receiving palliative care.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

In healthy individuals, blood capillaries and lymphatic structures support fluid exchange at the blood capillary–interstitial–lymphatic interface. Capillary pressure, negative interstitial pressure, and interstitial fluid colloid osmotic pressure collectively exert approximately 41 mm Hg outward pressure, and plasma colloid osmotic pressure exerts 28 mm Hg inward pressure, resulting in a net filtration pressure of 13 mm Hg from the arterial side of capillaries into the interstitial space (Guyton & Hall, 2000). Approximately 90% of this fluid reenters the blood circulatory system through venous ends of capillaries, and the remaining 10% enters lymphatic collectors. Fluid return to the venous end of the capillary is facilitated by the net venous reabsorption pressure of 7 mm Hg created by the imbalance between capillary, negative interstitial, and interstitial fluid colloid pressure of 21 mm Hg outward pressure and the inward plasma colloid osmotic pressure of 28 mm Hg (Guyton & Hall, 2000). Fluid and the larger protein molecules enter the lymphatic system through small one-way valves and are moved by contraction of lymphangions (segments of vessels), contraction of surrounding muscles, and contractile filaments in the endothelial cells through the lymphatic vessels into the blood circulatory system (Ridner, 2002).

When the lymphatic system can no longer transport the normal fluid and protein load or when there is reduced lymphatic transport capacity coupled with increased lymph, lymphedema develops (Browse et al., 2003; Foldi et al., 2003). Lymphedema can arise from either primary (idiopathic) or secondary (acquired) conditions. Primary lymphedema occurs in the presence of malformation of lymph vessels and/or lymph nodes and is associated with many medical conditions (Table 30-1). Primary lymphedema is classified based on timing of first noted swelling (Foldi et al., 2003):

| Primary Lymphedema: Associated Diseases | |

|---|---|

| Nonne-Milroy syndrome | Hennekam syndrome |

| Turner syndrome | Mixed vascular and lymphatic disorders |

| Noonan syndrome | Milroy syndrome |

| Fibrosis of inguinal nodes | Meige syndrome |

| Yellow nail syndrome | Lymphedema and distichiasis |

| Adams-Olivier syndrome | Neurofibromatosis |

| Proteus syndrome | Aagenaes syndrome |

| Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome | Prader-Willi syndrome |

| Secondary Lymphedema: Selected Causes | |

| Category | Examples |

| Infection | Filariasis, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, postsurgical infection |

| Trauma | Surgery, automobile accident, crush injuries, burns, vein removal, self-inflicted injury |

| Cancer and cancer treatment | Tumor occluding lymphatic structures (new or recurrent), lymphatic-infiltrating metastatic disease, Kaposi’s sarcoma, surgery, radiation, and postsurgical infection |

| Venous disease | Postthrombic conditions, venous ulcerations, intravenous drug abuse causing venous thrombosis and/or abscesses |

| Immobility | Paralysis, extreme fatigue, venous stasis |

| Inflammation | Rheumatoid arthritis, dermatitis, psoriasis |

▪ Congenital lymphedema, present at birth

▪ Lymphedema praecox, develops after birth but before age 35

▪ Lymphedema tarda, develops after age 35

Secondary lymphedema, lymphedema with a known cause, is the most common lymphedema in developed countries (see Table 30-1). It can occur immediately after the known insult to the lymphatic system or have a latency stage and appear many years later (Foldi et al., 2003). Any patient who has had a lymph node dissection or a tumor that impedes lymphatic circulation is at risk for developing lymphedema.

Both primary and secondary lymphedema may appear first as acute and then chronic disease (lasting longer than 6 months) that can progress over time through three stages of severity. Physical presentation of swelling is the same regardless of cause. Initially, in grade I, the limb will swell and pit with pressure, and elevation will relieve the swelling. In grade II, the limb will become firmer, not pit with pressure, and skin changes, hair loss, and alteration in nails may be noted. In grade III, elephantiasis results with very thick skin and large skin folds (Pain & Purushotham, 2000).

ASSESSMENT AND MEASUREMENT

Lymphedema assessment may entail evaluation of new-onset acute swelling or preexisting lymphedema. In both cases, it is imperative to assess immediately for infection and, if present, initiate treatment (Feldman, 2005; Olszewski, 2005; Weissleder & Schuchhardt, 2001) (Table 30-2). Awakening with a hot, painful, swollen limb may be the first sign or symptom of lymphedema onset. Likewise, individuals with chronic lymphedema can rapidly develop cellulitis or lymphangitis. Infections can quickly escalate into emergency situations such as life-threatening septicemia. When assessing infection, look for redness, spreading either locally or in a distinct red line. Touch the area to determine if it is warm and/or painful. Observe for oozing or drainage in the area. Check the patient’s temperature. Palpate for enlarged nodes. Many patients report feeling flu-like symptoms both before and after immediate signs of infection, so inquire about aching, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, weakness, dizziness, chills, or sweating. Any of these signs or symptoms requires immediate antibiotic treatment, and, in the case of a patient near end-of-life, hospitalization may be considered.

| Symptom | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Bruising | ||

| Rash | ||

| Blistering | ||

| Dusky in color | ||

| Unusual hair loss | ||

| Swelling | ||

| Enlarged lymph node | ||

| Oozing fluid | ||

| Pitting with pressure | ||

| Hard, nonpitting | ||

| Dry and/or flaky | ||

| Hard, nonpitting | ||

| Raised lumps | ||

| Cracking | ||

| Warm to touch | ||

| Cool to touch |

When an infection is present and appropriately treated and if no signs or symptoms of infection are noted, both subjective and objective manifestations of lymphedema and associated psychological sequelae should be assessed.

Subjective Symptoms

Subjective indicators may include patient-reported swelling, jewelry or clothing feeling tight, and feeling of heaviness in limbs (Armer, Radina, Porock et al., 2003). For patients with chronic lymphedema, alteration in limb sensation (heaviness, tightness, aching, burning, swelling, hardness, stabbing, pins and needles, and numbness) and fatigue may be reported (Armer & Porock, 2001; Ridner, 2005). Patients may also report a decrease or change in physical activity and demonstrate signs of psychological distress, such as depressed mood, frustration, anger about the swelling, and feeling helpless to manage their condition (Ridner, 2005). These subtle or overt changes in sensation may be the first indicators of lymphedema, lymphedema progression, or complications such as infection prior to objective changes.

Objective Signs

Currently, there is no accepted “gold standard” for objective measurement of limb swelling associated with lymphedema. However, multiple methods can be used to measure swelling in affected limbs: (1) water displacement, (2) limb girth measured in cm with a tape measure, (3) infrared laser scanning, and (4) bioelectrical impedance. It is notable that swelling associated with truncal, breast, genital, and head and neck lymphedema may be best assessed with subjective symptom report and observation, as objective fluid assessment measurements are, at best, limited.

Water displacement: Patients are required to remove clothing covering the swollen limb and then to place the uncovered limb in a cylinder of water. The amount of water displaced by the limb estimates the limb volume (Megens, Harris, Kim-Sing et al., 2001). Limbs with wounds cannot be assessed with water displacement. End-of-life patients may be too frail, weak, and fatigued to extend the limb vertically into the water displacement volumeter until overflow dripping stops.

Circumferential measurement: Patients must remove all limb coverings and sit, extending limbs horizontally while measurement increments are marked on their skin or on a strip of adhesive tape attached to the skin. A nonstretch tape is then placed around the limb at intervals of 10, 5, or 4 cm from wrist to axilla or ankle to groin. Both limbs are measured for comparison at similar anatomic or centimeter locations, or total bilateral limb volume is calculated for comparison. This is the most commonly used method of limb volume measurement in clinical settings; however, measurement error may potentially mask lymphedema occurrence or progression or falsely implied lymphedema (Armer, 2005).

Perometer: This optoelectronic volumetry device (Juzo, Cuyahoga Falls, OH) uses infrared laser technology (Petlund, 1991). The perometer estimates total limb volume and records limb shape, using PeroPlus computer software (Juzo, 2002). Clothing must be removed from the limb before measurement. The size and nonportable nature of the machine require that patients come into the clinic for limb measurement.

Bioelectrical impedance: A bioelectrical impedance device known as the Lymphometer (ImpediMed, Queensland, Australia) is being used in research settings to estimate limb volume and assess presence of lymphedema. This device uses low-voltage electric current to determine extracellular fluid (lymph) (Cornish, Chapman, Thomas et al., 2000). Clothing remains on, the procedure is quick and painless, and the device is portable.

Varying standards are used to diagnose lymphedema. For example, a 2- to 10-cm increase in circumference, 200-ml limb volume increase, or a 5% to 10% limb volume increase, compared with prior measurements in the same area or to the contralateral limb, is a standard for the definition of lymphedema as cited in the literature (Bland, Perczyk, Du et al., 2003). Thus, measurements falling within these ranges may indicate lymphedema. When using bioelectrical impedance, ratios of affected to unaffected limb volumes are calculated; manufacturer-suggested cut points for possible lymphedema have been established.

In addition to actual volume measurement, asymmetry in limbs, head and neck, trunk, or genital areas due to swelling secondary to lymph fluid accumulation may be observed. In some cases, Stemmer’s sign may be present. This skinfold sign is typically assessed by placing a finger on each side of the base of a toe or finger and squeezing gently; in addition, use of this technique in other body segments, such as limbs and trunk, has been documented (Weissleder & Schuchhardt, 2001). When lymphedema is present, a thickening of this fold is noted when compared to a nonlymphedematous digit. However, the absence of Stemmer’s sign does not rule out lymphedema.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

When conducting a history and physical examination of a patient with lymphedema, it is important to keep in mind possible differential (or comorbid) diagnoses, such as myxedema, lipidema, deep vein thrombosis, cancer recurrence, chronic venous insufficiency, cellulitis, or other infections (Rockson, 2001).

History should include the following:

▪ Review of all current and prior medical diagnoses including infections

▪ Course of current illness including onset (new or preexisting) of swelling, location of swelling, and exacerbation and remission of symptoms

▪ Review of current medications and medical treatment (e.g., radiation, surgery, antibiotic therapy, etc.)

▪ Review of possible causes (surgery, tumor, previous trauma)

▪ Family history of lymphedema or possibly undiagnosed chronic limb and/or body swelling

▪ Symptom review: heaviness or other sensations in affected area, skin crease depth in limb, perceived swelling, tighter-fitting clothing or jewelry on the affected side, pain, decrease or difficulty in mobility

Physical examination should include the following:

▪ Location and spread of swelling

▪ Signs of infection as previously discussed

▪ Volume measurement if possible

▪ Determination of stage of lymphedema

▪ Skin assessment (see Table 30-2)

DIAGNOSTICS

Lymphedema onset is often multifactorial and challenging to diagnose in palliative care settings (Cheville, 2002). For this reason, it is helpful to distinguish between the progression of established lymphedema due to diminished efficacy of treatment and edema related to direct tumor spread and/or other systemic factors (Cheville, 2002). Many cancer patients with secondary lymphedema experience progression of previously controlled lymphedema with advancing disease, largely due to reduced ability to adhere to the rigorous complete decongestive therapy (CDT) maintenance regimen (Cheville, 2002). Further, lymphedema may develop or progress secondary to direct tumor spread, independently of the adequacy of a CDT program (Cheville, 2002). For example, new-onset edema in the legs, genitalia, and/or lower trunk may reflect tumor recurrence, particularly in cancers such as cervical, uterine, ovarian, prostate, and lymphomas. Palliative radiation therapy to reduce tumor bulk or slow disease progression may also cause lymphedema. Additionally, certain systemic conditions associated with advancing illness may produce or exacerbate lymphedema (e.g., fluid and electrolyte imbalances, reduced protein synthesis, renal failure, and compromised cardiac function) (Cheville, 2002).

If, after completion of the history and physical examination, additional information is needed to make a differential diagnosis and/or to determine type of treatment, additional diagnostic testing can be done. Potential risks, possible discomfort, and cost must be balanced with potential benefits, including whether the overall plan of care and, specifically, care for the swollen limb, will be affected by the findings.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), duplex scanning, or phlebography can be used to rule out deep vein thrombosis (Townsend et al., 2001). MRI, ultrasonography, or phlebography can be used to rule out chronic deep venous insufficiency. Computed tomography scans can help identify lymphatic obstructions and guide lymphedema therapists to potentially unobstructed drainage pathways that can be used during treatment (Cheville, 2002).

Lymphoscintigraphy, the primary diagnostic method used to visualize the lymphatics (Williams, Witte, Witte et al., 2000), must be done in a nuclear medicine setting by an experienced clinician. This procedure involves injection of a radioactively tagged tracer and scanning to evaluate lymph flow and lymphatic structure. It is used frequently to determine the structural cause of lymphedema and, in some situations, to monitor the effectiveness of treatment (Szuba, Strauss, Sirsikar et al., 2002).

INTERVENTION AND TREATMENT

Clinician collaboration with certified lymphedema therapists, the patient, and caregiver(s) is needed to determine if the risks and discomforts associated with the treatment outweigh potential benefits. In patients nearing death, no treatment may be needed, unless infection is present. Successful treatment of lymphedema is directly related to understanding the underlying pathological condition(s) causing the problem and its accompanying symptoms. Sometimes it may not be possible to control worsening lymphedema. Thus, it is imperative that in addition to initiating treatment for the swelling, the clinician must also intervene as needed for symptoms such as pain, depressed mood, increased fatigue, difficulties in carrying out activities of daily living, and decreased self-esteem (Geller, Vacek, O’Brien et al., 2003; Ridner, 2005). If generalized infection is present, the use of compression bandages, manual lymph drainage, and exercises should be stopped until the patient is afebrile, skin temperature returns to normal, and erythema is receding (Feldman, 2005). If there is an open wound, it must be addressed immediately.

|

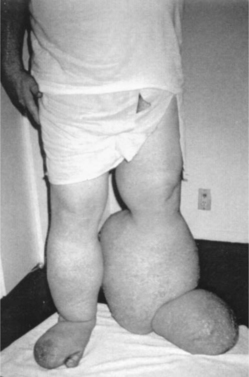

| Figure 30-1. |

| Below-knee lymphedema before treatment. |

|

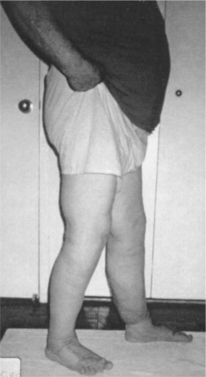

| Figure 30-2. |

| Below-knee lymphedema after treatment. |

Infection Management

Because microorganisms penetrating the skin may trigger infections, meticulous skin care among patients with lymphedema is a necessary preventative measure. When infection occurs, Olszewski (1996, 2005) recommends skin bacteriological cultures for patients experiencing frequently recurring episodes of dermatitis, lymphangitis, and lymphadenitis and treatment with effective antibiotics such as penicillin or erythromycin.

Dermatolymphangioadenitis (DLA) may occur in persons with chronic lymphedema and is followed by an increase in swelling in the affected area (Olszewski, 2005). Episodes of DLA are most frequently observed in the postsurgical, posttraumatic, and postdermatitis types of secondary lymphedema, as well as in the late and advanced stages of primary forms (Olszewski, 2005). Among the bacterial strains most commonly isolated are Staphylococcus epidermidis and other coagulase-negative staphylococci, micrococci, and Acinetobacter but not streptococci. Antibiotics for acute episodes should be prescribed based on the causative agent. Once a patient has had DLA, it frequently recurs. To prevent DLA recurrence, Olszewski (2005) recommends administration of long-term (minimally over 3 months and up to 12 months)intramuscular penicillin accompanied by local anesthetic. Oral penicillin may be considered for those able to swallow. For patients with penicillin allergy, erythromycin is given orally for an extended period of time (3 to 12 months).

Lymphedema Management

When treating lymphedema, the current “gold standard” treatment is CDT, a two-phase treatment protocol for both primary and secondary lymphedema (Badger, Preston, Seers et al., 2004; Harris, Hugi, Olivotto et al., 2001; Rockson, 2001). Phase 1 consists of intensive, manual lymphatic drainage (MLD), a specialized massage; around-the-clock two-way short-stretch compression bandaging; a program of exercises; and meticulous skin care. Phase 2, the maintenance phase, includes life-long wearing of daytime elastic sleeves or stockings, nighttime compression wrapping, exercises, and skin care. To work consistently in palliative care, conventional approaches to lymphedema management such as CDT may need to be modified substantially (Cheville, 2002). For example, compressive bandaging may need to be modified due to skin metastases, painful areas, radiation burns, pathological fractures, and other adverse conditions. Further, if lymphatic obstruction is undetectable with conventional imaging, the therapist may have to rely on anatomic understanding of the lymphatic system to identify patient drainage pathways (Cheville, 2002). Thus, lymphedema therapists and clinicians must work together and recognize that their attention, acceptance of the patient, and willingness to adapt and persevere may be, in and of themselves, therapeutic independent of objective improvement (Cheville, 2002). Table 30-3 discusses adaptations of CDT for palliative care needs.

| Key Considerations | Description |

|---|---|

| Skin breakdown | Compression will limit edema and facilitate diffusion of oxygen and nutrients. Place compressive bandages over painless areas of skin breakdown that are free of infection. Dressings should not adhere to the wound. Use petroleum jelly–impregnated or other nonadherent gauze to avoid discomfort during dressing changes. Adhering bandages or dressing materials can be “soaked off” to prevent ripping the skin. Change bandages BID if skin breakdown occurs within the area of CDT treatment. Instruct patient and caregivers on safe and effective bandaging. |

| Bandaging materials | Tailor palliative CDT program for each patient. Use Artiflex or extra foam padding to protect bony prominences. Use fewer than normal bandages for patients whose additional care is demanding and when maintenance rather than reduction of limb volume is goal. Protect skin adjacent to wrapped areas if taut, irritated, or friable. Cut Tubigrip and sew to protect surrounding skin from abrasive short-stretch bandages. If lymphorrhea is present, to absorb moisture, use calcium alginate padding next to the skin. Apply impermeable membrane just outside the alginate to avoid wet bandages. |

| Anticipate progression | Phase II (maintenance) CDT program must consider future functional deterioration. Educate patient and caretakers in strategies to adapt and modify their phase II program. Consider use of a Mediassist device, Legacy or Tribute garment, or Reid Sleeve to increase the probability of success. Donning garments is difficult for weak patients. Layer two compressive garments of a lower class or use a zippered garment. |

| Remedial exercise | Consider progressive weakness. Exercise performance with gravity eliminated may extend the utility of the program. Modify exercises in consideration of plegic or painful structures. Do not stress skeletal structures with potential bone metastases. Obtain a report of most recent bone scan or skeletal survey to use in devising a safe and humane exercise program. |

| Manual lymphatic drainage | Clinician and therapist must work closely with the interdisciplinary palliative care team and familiarize themselves with malignant sources of lymphatic obstruction. Lymphatic obstruction may be undetectable by conventional imaging. In such cases, anatomic understanding of the lymphatic system is critical to identify patent drainage pathways. |

Sequential pneumatic compression pumps, single or multicompartmentalized compression devices consisting of cells that deflate and inflate, are sometimes used as an alternative to CDT when access to lymphedema therapists or caregivers is limited and the patient has limited mobility or energy. When properly applied, these pumps move fluid proximally within the limb but cannot move fluid from the limb into the trunk as does CDT (Rockson, 2001). When the patient or caregiver has limited energy or mobility for completion of the full range of CDT, the pump may also be used in conjunction with modified CDT techniques to aid movement of fluid from the limb into the trunk. Caution must be taken to prevent tissue injury and worsening of lymphedema and related symptoms due to inappropriate placement and pressures greater than sustainable by the fragile lymphatic collectors (Boris, Weindorf, & Lasinski, 1998; Eliska & Eliskova, 1995).

Although careful monitoring and frequent revision to lymphedema treatment modalities are required in palliative care settings, the therapeutic benefits of treatment, such as reestablishing the patient’s perception of control, empowerment of caregivers, reducing infection risk, improving mobility, and decreasing risk of skin breakdown, make such treatment an important component of palliative care for individuals with lymphedema (Cheville, 2002).

EVALUATION AND FOLLOW-UP

Volume reduction treatment in the initial intensive phase (and in regular lymphatic follow-up sessions after intensive therapy) usually continues until limb volume plateaus. At that point, patients are transitioned to at-home self-care techniques. Once a patient has been diagnosed with lymphedema, the clinician will need to observe for any change in the lymphedematous area at each patient visit. This evaluation should include assessment for signs and symptoms of infection, increased swelling, pain, and emotional distress. Table 30-4 details situations requiring referral to specialists in lymphedema management.

| Category | Patient Status | Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Mild and uncomplicated edema |

▪ Excess limb volume < 20%

▪ No trunk, head, or genital swelling

▪ No arterial insufficiency or malignancy

|

▪ Education, information, and advice

▪ Daily: skin care, exercise, simple lymphatic drainage, and compression

▪ Monitoring and referral if required

|

| Moderate to severe, complicated edema |

▪ Excess limb volume >20% with trunk, head, or genital edema

▪ Distorted limb shape

▪ Skin problems

▪ Evidence of active controlled malignancy, arterial and/or venous insufficiency, current acute inflammatory episode, and/or lymphorrhea

|

▪ Education, information, and advice

▪ Multilayer LE bandaging, manual lymph drainage, isotonic exercises, skin care, compression garments

▪ Referral to other members of the health care team

▪ Transfer to maintenance program as required

|

| Edema and advanced disease |

▪ Edema associated with advanced disease

▪ Trunk and/or midline edema, lymphorrhea, tension in the tissues, impaired mobility and function, pain, infection

|

▪ Education, information, and advice

▪ Emphasis on quality of life

▪ Daily skin care, support and positioning of the limb, exercises, lymphatic drainage

▪ Specialist interventions such as manual lymphatic drainage, modified multilayer bandaging, compression garments, appliance to aid mobility and function

|

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

Clinicians and lymphedema therapists caring for the patient must communicate clearly with each other and with the patient and caregivers. Issues such as how and who will provide the self-care required after hands-on, phase I intensive professional therapy is completed must be clearly understood. Information about restrictions on activity must also be provided and instructions on how to assist the patient during movement given. Self-care will include daily cleaning of the skin in the swollen area with nonsoap or mild soap or cleansers, drying the area thoroughly, and applying oil-based pH-neutral creams or lotions to maintain hydration. Unscented products are recommended (Mortimer & Badger, 2004). Patients and caregivers should be taught signs or symptoms of infection and to examine the patient for such signs or symptoms during each cleaning and instructed to contact the clinician immediately if any are noted. Prescribed garments or bandages should be applied and patients and caregivers warned to never use nonprescribed alternatives such as Ace bandages. Patients and caregivers need to be encouraged to tell the clinician when the burdens of lymphedema or its treatment become overwhelming.

CONCLUSION

Lymphedema is a distressing problem for the palliative care patient and his or her family. Timely assessment for the presence and/or worsening of lymphedema and quick intervention are necessary to provide patient comfort. Management of any developing infection in the swollen area is imperative. If treatment becomes too burdensome for the patient, the clinician should reevaluate and modify treatment goals accordingly.

H., age 79, is a widowed, intermediate-level nursing care facility resident. She is alert and articulate and has a keen interest in the bustling activity around her. She is a 26-year breast cancer survivor who underwent a radical mastectomy. Three months ago, H. was told the pain in her back and ribs was due to metastasis of her breast cancer. Although the prognosis is uncertain, palliative care is planned. H. has had grade II lymphedema of the left arm for 10 years. The arm is approximately one-and-a-half times larger than the other arm; by circumferential assessment, limb volume is 1000 ml greater on the affected side. The arm is brawny, nonpitting, and firm to palpation. When she is in a wheelchair, she wears a hemiplegic-style sling due to heaviness of the limb and her inability to bear the weight of the limb without assistance. She cannot manage her four-legged walker because of weakness and heaviness of the limb. She has weeping (lymphorrhea) and occasional “shooting” pains in the arm and has had six episodes of cellulitis over the past 18 months, with each episode treated with oral antibiotics. H. takes oral medication for hypertension and diabetes, has stress incontinence due to a “fallen” uterus (treated palliatively with a pessary, which is managed with nursing assistance), and takes an antiinflammatory medication as needed for arthritis pain. She limits her fluids through the day and especially at bedtime due to worry about “accidents” from stress incontinence.

H. says she has a “fat arm” that she knows “no one wants to look at.” She has not been fitted for a compression sleeve for many years and does not regularly wear a sleeve in the daytime or a bandage at night. She has never had CDT, as her doctor once told her there was no effective treatment to “cure” the lymphedema. Over the years, her only treatment has been the occasional wearing of a heavy flesh-colored sleeve that was “too hot” in warm weather, “bothersome” in doing her gardening and housework, and “not very pretty” to wear in public.

The clinician is asked to see H. today because a 4-day wound has failed to heal after her forearm on the affected side was injured during a wheelchair transfer. The wound has a border of a 0.5-cm ring of erythema and produces a colorless exudate. The surrounding area is warm to the touch and the forearm is tender. No elevation of temperature is noted.

Plan of care to manage the wound on the affected arm and the lymphedema:

Discuss goals in managing her lymphedema. Incorporate her goals and priorities for herself and her health in the plan of care in view of the recent evidence of breast cancer progression.

Clean and dress wound with petroleum jelly impregnated gauze over antibiotic cream (e.g., Bactroban) twice daily.

Administer oral antibiotics (erythromycin because of a history of penicillin allergy) for 14 days.

Monitor hydration and nutrition, including adequate dietary protein. Explain to H. that adequate fluid intake is necessary for healing and maintaining health and comfort, and that concentrated urine is associated with more frequent urination and increased risk of a urinary tract infection.

Refer to a therapist(s) with special training in lymphedema management to assess eligibility and readiness for a course of intensive CDT therapy. Assess H.’s openness to CDT for comfort, as well as for reduction of limb volume.

Determine alternative strategies for reducing limb volume and weeping to promote comfort and healing and to reduce risk of future infection. Explore use of a washable, custom-fit, foam-filled compression garment (e.g., Legacy, Tribute) to facilitate healing, reduce limb volume, and improve comfort.

Evaluate need for pain medication. Encourage elevation of the affected arm on a soft pillow to reduce fluid accumulation as a result of being in a dependent position.

Educate patient, family, and staff on how to care for limb: keep area clean, elevate swollen arm, observe for redness, heat, or foul odor.

With the complexities and stressors of advanced disease, the posttreatment consequence of lymphedema, and other comorbidities, H.’s case is challenging—and not so unusual in the world of chronic illness and palliative care. As in this case study, individualized, holistic, and multidisciplinary patient care partnered with ongoing education of patients and staff are key ingredients in treatment plans that can improve quality of life.

REFERENCES

Armer, J.M., The problem of post-breast cancer lymphedema: Impact and measurement issues, Cancer Investigation 1 (2005) 71–77.

Armer, J.; Porock, D., Self-reported fatigue in women with lymphedema, LymphLink 13 (3) ( 2001) 1–4.

Armer, J.M.; Radina, M.E.; Porock, D.; et al., Predicting breast cancer-related lymphedema using self-reported symptoms, Nurs Res 52 (2003) 370–379.

Badger, C.; Preston, N.; Seers, K.; et al., Physical therapies for reducing and controlling lymphedema of the limbs. Cochrane Breast Cancer Group, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4 (2004)CD003141..

Bland, K.L.; Perczyk, R.; Du, W.; et al., Can a practicing surgeon detect early lymphedema?Am J Surg 186 (2003) 509–513.

Boris, M.; Weindorf, S.; Lasinski, B., The risk of genital edema after external pump compression for lower limb lymphedema, Lymphology 31 (1998) 15–20.

British Lymphology Society, Chronic oedema population and need, Retrieved March 22, 2006, from www.lymphoedema.org/bls/membership/definitions.htm ( 2006).

Browse, N.; Burnand, K.G.; Mortimer, P.S., Diseases of the lymphatics. ( 2003)Arnold, London, England.

Cheville, A.J., Lymphedema and palliative care. National Lymphedema Network, LymphLink 14 (2002) 1–4; (reprint).Retrieved from www.lymphnet.org/newsletter/newsletter.htm.

Cornish, B.H.; Chapman, M.; Thomas, B.J.; et al., Early diagnosis of lymphedema in post-surgery breast cancer patients, Ann N Y Acad Sci 904 (2000) 571–575.

Eliska, O.; Eliskova, M., Are peripheral lymphatics damaged by high pressure manual massage?Lymphology 28 (1995) 21–30.

Feldman, J.L., The challenge of infection in lymphedema. National Lymphedema Network, LymphLink ( 2005); October.

In: (Editors: Foldi, M.; Foldi, E.; Kubik, S.) Textbook of lymphology for physicians and lymphedema therapists ( 2003)Urban & Fischer, Munchen, Germany.

Geller, B.M.; Vacek, P.M.; O’Brien, P.; et al., Factors associated with arm swelling after breast cancer surgery, J Women Health 12 (2003) 921–930.

Guyton, A.C.; Hall, J.E., Textbook of medical physiology. 10th ed. ( 2000)Saunders, Philadelphia.

Harris, S.R.; Hugi, M.R.; Olivotto, I.A.; et al., Clinical practice guidelines for the care and treatment of breast cancer lymphedema, Can Med Assoc J 164 (2001) 191–199.

Juzo Compression Therapy Garments, Perometer Plus: A complete compression garment measurement system. ( 2002)Author, Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio..

Logan, V.B., Incidence and prevalence of lymphedema: a literature review, J Clin Nurs 4 (1995) 213–219.

Megens, A.M.; Harris, S.R.; Kim-Sing, C.; et al., Measurement of upper extremity volume in women after axillary dissection for breast cancer, Arch Phys Med Rehabil 82 (2001) 1639–1644.

Mortimer, P.S.; Badger, C., Lymphoedema, In: (Editors: Doyle, D.; Hanks, G.; Cherney, N.I.; Calmans, K.) Oxford textbook of palliative medicine3rd ed. ( 2004)Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Muscari, E., Lymphedema: Responding to our patients’ needs, Oncol Nurs Forum 31 (2004) 905–912.

Olszewski, W.L., Inflammatory changes of skin in lymphedema of extremities and efficacy of benzathine penicillin administration. National Lymphedema Network, LymphLink 8 (1996) 1–2.

Olszewski, W.L., An alternative viewpoint from across the world on the management of infections in LE. National Lymphedema Network LymphLink, Retrieved from www.lymphnet.org/newsletter/newsletter.htm ( 2005); October.

Pain, S.J.; Purushotham, A.D., Lymphedema following surgery for breast cancer, Br J Surg 87 (2000) 1128–1141.

Petlund, C.F., Volumetry of limbs, In: (Editor: Olszewski, W.L.) Lymph stasis: Pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment ( 1991)CRC Press, Boston, pp. 444–451.

Petrek, J.A.; Pressman, P.I.; Smith, R.A., Lymphedema: Current issues in research and management, CA Cancer J Clin 50 (2000) 292–307.

Ridner, S.H., Breast cancer lymphedema: Pathophysiology and risk reduction guidelines, Oncol Nurs Forum 29 (2002) 1285–1293.

Ridner, S.H., Quality of life and a symptom cluster associated with breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema, Support Care Cancer 13 (2005) 904–911.

Rockson, S.G., Lymphedema, Am J Med 110 (2001) 288–295.

Szuba, A.; Strauss, W.; Sirsikar, S.P.; et al., Quantitative radionuclide lymphoscintigraphy predicts outcome of manual lymphatic therapy in breast cancer-related lymphedema of the upper extremity, Nucl Med Commun 23 (2002) 1171–1175.

Townsend Jr., C.M.; Beauchamp, R.D.; Evers, B.M.; et al., Sabiston textbook of surgery: The biological basis of modern surgical practice. 16th ed. ( 2001)Saunders, Philadelphia.

In: (Editors: Weissleder, H.; Schuchhardt, C.) Lymphedema diagnosis and therapy ( 2001)Germany: Viavital Verlag GmbH, Köln [Cologne].

Williams, A., An overview of non-cancer related chronic oedema—A UK perspective, Retrieved December 12, 2004, from www.worldwidewounds.com/2003/april/Williams/Chronic-Oedema.html ( 2004).

Williams, W.H.; Witte, C.L.; Witte, M.H.; et al., Radionuclide lymphangioscintigraphy in the evaluation of peripheral lymphedema, Clin Nucl Med 25 (2000) 451–464.

Winn, P.A.; Dentino, A.N., Quality palliative care in long-term care settings, J Am Med Dir Assoc 5 (2004) 197–206.