CASE 30 Intracranial Hemorrhage After Coronary Intervention

Catheterization

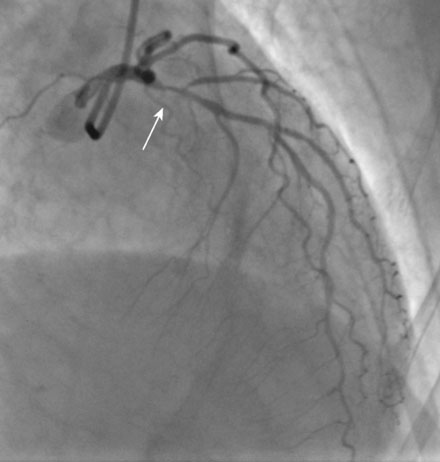

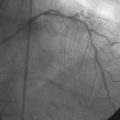

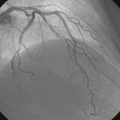

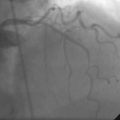

Left venticulography revealed mild anterior hypokinesis with preserved ejection fraction. Coronary angiography found no evidence of obstructive disease in the right or left circumflex coronary arteries. Severe atherosclerotic narrowing of the proximal segment of the left anterior descending artery was likely the explanation for her acute coronary syndrome (Figures 30-1, 30-2 and Videos 30-1, 30-2). Atherosclerosis also involved the first diagonal branch and the midsegment of the left anterior descending artery, but these lesions were felt to be nonobstructive. The lesion in the proximal segment of the left anterior descending artery was treated with balloon angioplasty followed by placement of a everolimus-eluting stent (2.5 mm diameter by 15 mm long) with an excellent angiographic result (Figure 30-3 and Video 30-3), and intravascular ultrasound confirmed stent apposition. The dose of enoxaparin planned for the morning of the procedure was held (last dose greater than 12 hours from catheterization) and procedural anticoagulation consisted of bivalirudin (33 mg intravenous bolus followed by an intravenous infusion of 1.7 mg/kg/hr) and 600 mg of clopidogrel administered orally at the time of the intervention. Hemostasis was achieved with a femoral artery closure device and she returned to a telemetry unit feeling well with no complaints.

Discussion

Cerebrovascular accidents are a rare but dreaded complication of percutaneous cardiovascular procedures, occurring in 0.2% to 0.4% of procedures and associated with a high mortality.1,2 Most of these events are caused by atheroembolism or clot. Despite the liberal use of procedural anticoagulation, intracranial hemorrhage is, fortunately, very rare. In large series of patients treated with bivalirudin, the risk of intracranial hemorrhage was exceedingly low (one event out of 2993 patients or 0.03%)3; the rate of intracranial hemorrhage when the more powerful glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are used is similarly very small at only 0.07%.3 Following intervention, anticoagulation is maintained using dual antiplatelet therapy with the risk of hemorrhagic stroke from the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel of only 0.1% with no difference from aspirin alone.4

1 Hamon M., Baron J.C., Viader F., Hamon M. Periprocedural stroke and cardiac catheterization. Circulation. 2008;118:678-683.

2 Aggarwal A., Dai D., Rumsfeld J.S., Klein L.W., Roe M.T., American College of Cardiology National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Incidence and predictors of stroke associated with percutaneous coronary intervention. On behalf of the Am J Cardiol 2009;104:349-353

3 Lincoff A.M., Bittl J.A., Harrington R.A., REPLACE-2 Investigators. Bivalirudin and provisional glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade compared with heparin and planned glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade during percutaneous coronary intervention REPLACE-2 randomized trial. For the JAMA 2003;289:853-863

4 CURE Study Investigators. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:494-502.