CHAPTER 30

Extensor Tendon Injuries

Definition

Extensor tendon injuries occur to the extensor mechanism of the digits. They include the finger and the thumb extensors and abductors. These injuries are more common than flexor tendon injuries because of their superficial position and relative lack of soft tissue between them and the underlying bone. As a result, the extensor tendons are prone to laceration, abrasion, crushing, burns, and bite wounds [1]. Demographic data defining age, gender, and occupation for the development of extensor tendon injury are not well documented. However, in our clinical experience, extensor tendon injuries commonly occur from lacerations, fist to mouth injuries, and rheumatologic conditions.

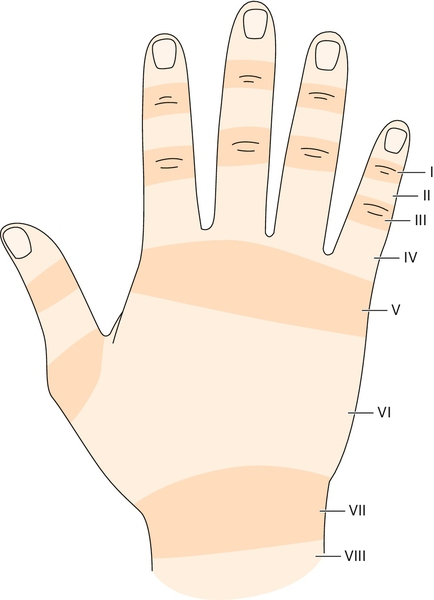

Extensor tendon injuries result in the inability to extend the finger because of transection of the tendon itself, extensor lag, joint stiffness, and poor pain control [2,3]. There are eight zones to the extensor mechanism where injury can result in differing pathomechanics [4] (Fig. 30.1).

Symptoms

Patients typically lose the ability to fully extend the involved finger (Fig. 30.2). This lack of motion may be confined to a single joint or the entire digit. Pain in surrounding regions often accompanies the loss of motion because of abnormal tissue stresses. Diminished sensation may be present if there is concomitant injury to the digital nerves.

Physical Examination

Physical examination begins with observation of the resting hand position. If the extensor tendon is completely disrupted, the unsupported finger will assume a flexed posture. Range of motion, both active and passive, is evaluated for each finger joint. Grip strength is commonly measured by use of a hand-held dynamometer. Individual finger extension strength can be recorded by manual muscle testing or finger dynamometry. Sensation should be checked because of the proximity of the extensor mechanism to the digital nerves. The radial and ulnar sides of the digit should be checked to assess light touch, pinprick, and two-point discrimination.

Functional Limitations

The positioning of the hand in preparation for grip or pinch is occasionally more important and limiting than the inability to grasp. Functional limitations therefore are manifested as the inability to produce finger extension in preparation for grip or pinch. As a result, writing and manipulation of small objects can be problematic. Patients may also have difficulty reaching into confined areas, such as pockets, because of a flexed digit with the limited ability to extend.

Diagnostic Studies

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the involved hand and fingers are obtained when there is a possibility of bone or soft tissue injury, such as fracture of a metacarpal from a bite wound, foreign body retention from glass or metal, or air in the soft tissues or joint space secondary to penetration of a foreign object. Ultrasonography is an inexpensive alternative to magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of foreign bodies and identification of traumatic lesions of tendons. However, ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging are generally not necessary but can be used to confirm clinical suspicion of chronic and partial extensor tendon injuries.

Treatment

Initial

The treatment protocols for extensor tendon injuries vary by zone, mechanism, and time elapsed since the injury. If the disruption of the extensor mechanism is due to a laceration, crush injury, burn, or bite, surgical referral is warranted. In open injuries, if repair is not immediate, appropriate antibiotics should be initiated, the injured tendon should be promptly irrigated, and primary coverage by skin suturing should be performed to protect the tendon and to decrease the potential for infection. The surgeon who will be performing the definitive repair should be contacted before this, however [5]. Conservative splinting can be attempted for closed zone I and zone II extensor tendon injuries.

Rehabilitation

Conservative treatment and splinting have been recommended for zone I and zone II injuries. Conservative treatment of injuries involving zones III through VIII has limited success in restoring normal range of motion and function. Acute injuries in these zones usually require surgical repair, and chronic injuries often require surgical review.

Zone I (Mallet Deformity)

Disruption of continuity of the extensor tendon over the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint produces the characteristic flexion deformity of the DIP joint [6]. Injury in this region is the result of a traumatic event, such as sudden forced hyperflexion of an extended DIP joint with tendinous disruption or avulsion fracture at the site of insertion. The digits most commonly involved are the long, ring, and small fingers of the dominant hand [7]. When it is left untreated for a prolonged time, hyperextension of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint (swan-neck deformity) may develop because of proximal retraction of the central band [6].

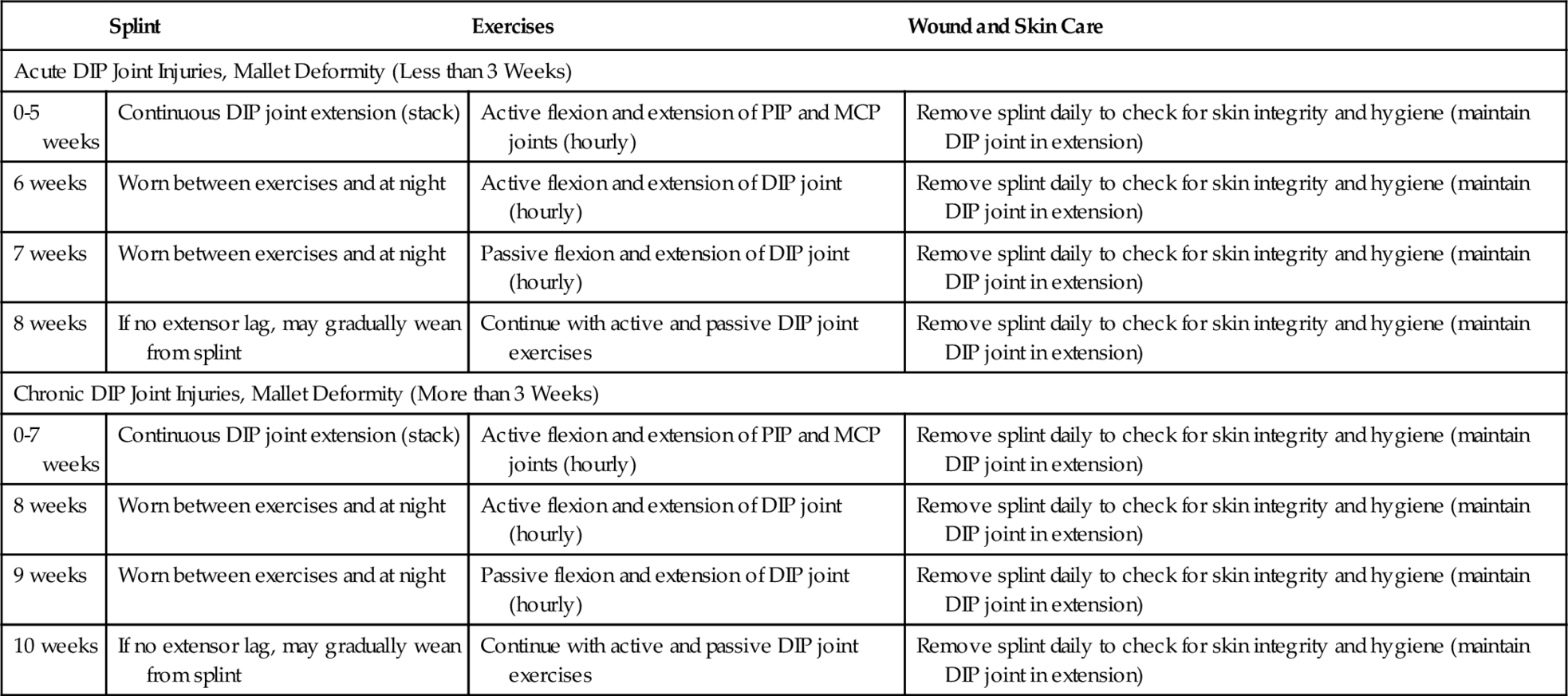

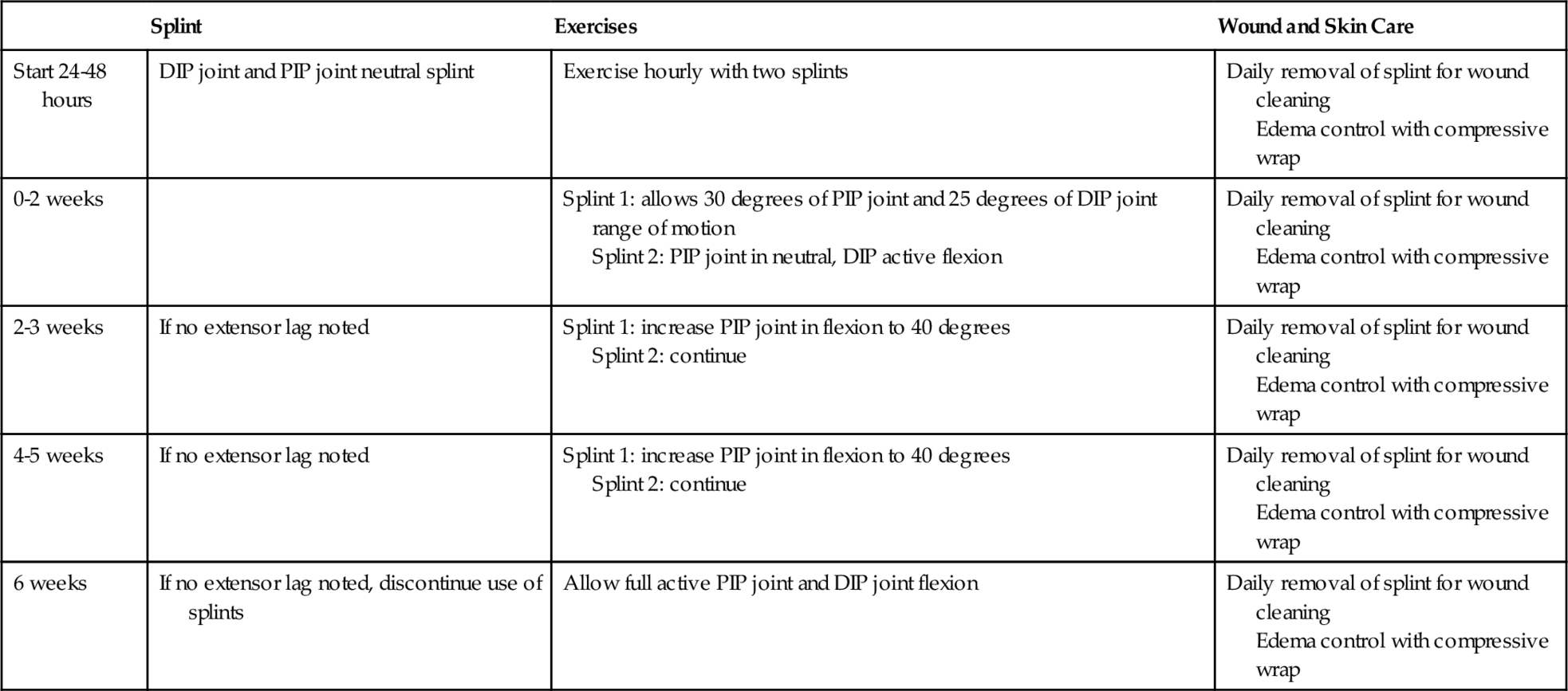

In a closed injury, the most common method of treatment is 6 weeks of continuous immobilization of the DIP joint in full extension or slight hyperextension (0 to 15 degrees) [8–12]. The DIP joint should not be immobilized in excessive hyperextension because of compromise of the vascular supply to the dorsal skin [7]. Stack splints are commonly used to achieve extension at the DIP joint. The splint should be worn continuously, except during hygiene. When the splint is removed, the DIP joint should be maintained in extension. If no extensor lag is identified after 7 weeks, range of motion exercises consisting of 10 repetitions hourly of passive, pain-free motion of the DIP joint can be initiated. The splint should be worn during exercise and at night. Splinting may be discontinued and exercises progressed to active extension after 8 weeks. In chronic mallet deformities, in which no treatment is initiated for 3 weeks after injury, splinting is recommended for 8 weeks before beginning of range of motion exercises (Table 30.1) [9,11,12].

Zone II

Injuries in zone II are often due to a laceration or crush injury. Treatment involves routine wound care and splinting for 7 to 10 days, followed by active motion if less than 50% of the tendon width is cut. If more than 50% of the tendon is cut, it should be repaired primarily, followed by 6 weeks of splinting [6].

Zone III (Boutonnière Deformity)

Zone III injuries usually result from direct forceful flexion of an extended PIP joint, laceration, or bite. If the lateral bands slip volarly, a boutonnière deformity results. The boutonnière deformity develops gradually and usually appears 10 to 14 days after the initial injury. Diagnosis is best made after splinting of the finger straight for a few days and reexamination of the finger after swelling subsides. Absent or weak active extension of the PIP joint is a positive, confirmatory finding [6].

Closed injuries are initially treated with 4 to 6 weeks of splinting of the PIP joint in extension with the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and wrist joints left free. The splint is reapplied for recurrence of deformity [6]. Displaced closed avulsion fractures at the base of the middle phalanx, axial and lateral instability of the PIP joint with loss of joint motion, and failed nonoperative treatment are indications for surgical intervention [6]. In addition, acute open injuries require primary surgical repair.

Postoperative rehabilitation has changed in recent years with the implementation of early protected motion [8–10,13]. Postoperatively, the finger is immobilized in a PIP joint gutter splint. This splint is removed hourly to perform guarded active motion exercises, which may consist of using two exercise braces that provide optimal gliding of the extensor mechanism (Table 30.2).

Zone IV

Injuries in zone IV usually spare the lateral bands. However, there is often considerable adhesion with resultant loss of motion that develops because of the intricate relationship of the tendon and bone in this area. Rehabilitation and splinting techniques are similar to those in zone III (see Table 30.2).

Zone V

Zone V is located over the MCP joints. This is the most common area of extensor tendon injuries resulting from bites, lacerations, or joint dislocation [1]. The injury more often occurs with the joint in flexion, so the tendon injury will actually be proximal to the dermal injury [6]. Acute open injuries are surgically repaired after thorough irrigation if they are not the result of a human bite or fist to mouth injury.

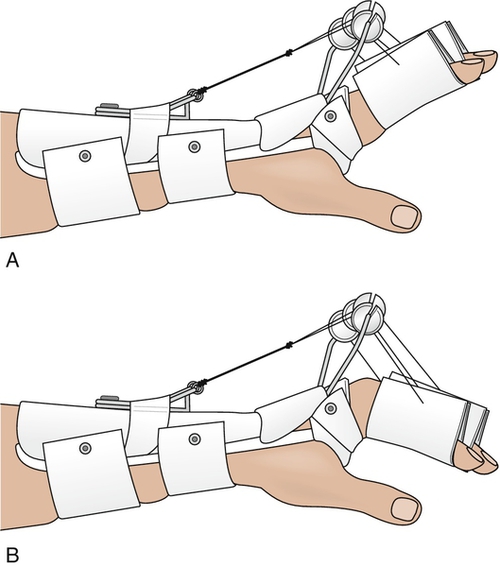

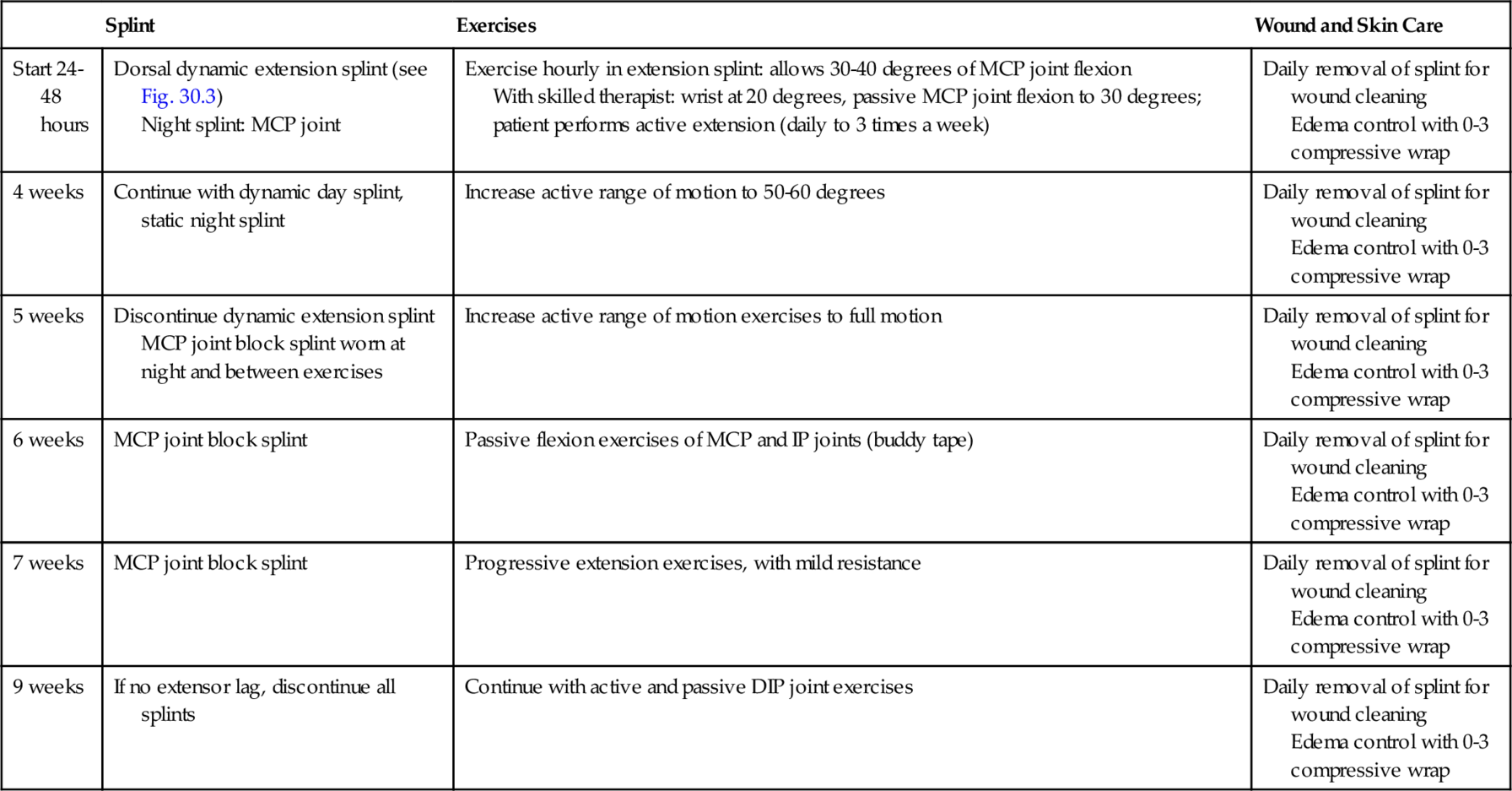

Many authors have recently recommended that dynamic splinting be initiated in the first week [8,9,11,12,14,15]. This is accomplished with a dorsal dynamic extension splint that has stop beads on the suspension line, which limits flexion (Fig. 30.3A). Patients are instructed to perform active flexion of the fingers hourly (Fig. 30.3B). The rubber band suspension provides passive extension. Therapy is initiated early by a skilled therapist by positioning the wrist in 20 degrees of flexion and passively flexing the MCP joint to 30 degrees. This provides for safe protected gliding of the extensor mechanism. At postoperative week 7, progressive strengthening exercises can be initiated. At week 9, all bracing may be discontinued if no extensor lag is present (Table 30.3).

Table 30.3

Zone V, Zone VI, and Zone VII Injuries

| Splint | Exercises | Wound and Skin Care | |

| Start 24-48 hours | Dorsal dynamic extension splint (see Fig. 30.3) Night splint: MCP joint |

Exercise hourly in extension splint: allows 30-40 degrees of MCP joint flexion With skilled therapist: wrist at 20 degrees, passive MCP joint flexion to 30 degrees; patient performs active extension (daily to 3 times a week) |

Daily removal of splint for wound cleaning Edema control with 0-3 compressive wrap |

| 4 weeks | Continue with dynamic day splint, static night splint | Increase active range of motion to 50-60 degrees | Daily removal of splint for wound cleaning Edema control with 0-3 compressive wrap |

| 5 weeks | Discontinue dynamic extension splint MCP joint block splint worn at night and between exercises |

Increase active range of motion exercises to full motion | Daily removal of splint for wound cleaning Edema control with 0-3 compressive wrap |

| 6 weeks | MCP joint block splint | Passive flexion exercises of MCP and IP joints (buddy tape) | Daily removal of splint for wound cleaning Edema control with 0-3 compressive wrap |

| 7 weeks | MCP joint block splint | Progressive extension exercises, with mild resistance | Daily removal of splint for wound cleaning Edema control with 0-3 compressive wrap |

| 9 weeks | If no extensor lag, discontinue all splints | Continue with active and passive DIP joint exercises | Daily removal of splint for wound cleaning Edema control with 0-3 compressive wrap |

From Brault J. Rehabilitation of extensor tendon injuries. Oper Tech Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;7:25-30.

When the wound is associated with a human bite, it is extensively inspected and débrided; culture specimens are obtained, and the wound is irrigated and left open. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are initiated. The hand is splinted with the wrist in approximately 45 degrees of extension and the MCP joint in 15 to 20 degrees of flexion. The wound typically heals within 5 to 10 days, and secondary repair is rarely needed [6].

Zone VI

Zone VI is located over the metacarpals. Injuries to this area have a clinical picture similar to that of zone V injuries and are treated as such (see Table 30.3) [9,11,12,14,15].

Zone VII

Zone VII lies at the level of the wrist. Tendons in this region course through a fibro-osseous tunnel and are covered by the extensor retinaculum. Complete laceration of the tendons in this region is rare. Tendon retraction can be a significant problem in this region, and primary repair is warranted, with preservation of a portion of the retinaculum to prevent extensor bowstringing [6]. Rehabilitation is similar to that in zone V (see Table 30.3).

Zone VIII

Zone VIII lies at the level of the distal forearm. Multiple tendons may be injured in this area, making it difficult to identify individual tendons. Restoration of independent wrist and thumb extension should be given priority [6]. Injuries in this location often require tendon retrieval for complete lacerations, and surgical intervention is warranted.

Postoperative rehabilitation consists of static immobilization of the wrist in 45 degrees of extension with the MCP joints in 15 to 20 degrees of flexion. Splinting is generally maintained for 4 to 5 weeks. However, early controlled motion with a dynamic extensor splint may help decrease adhesions and subsequent contractures. Dynamic motion of the MCP joints may be started at 2 weeks.

Procedures

Surgical repair is the mainstay for treatment of most extensor tendon injuries. Injections are typically not appropriate for the management of these conditions.

Surgery

Zone I and zone II injuries are typically treated nonoperatively, unless there is laceration of the terminal extensor slip (zone II injury), which may then require surgical repair. Surgical correction of zone I and zone II injuries usually results from failed conservative bracing, usually in a younger patient. In addition, patients may elect to have the terminal extensor tendon repaired or the DIP joint fused for cosmetic reasons. In older individuals with fixed deformities and painful arthritic conditions that limit function, joint arthrodesis is a reasonable approach.

Surgical intervention in zones III through VIII is usually primary repair of the injured extensor tendon mechanism. If primary repair is not possible, tendon grafting has been described [4,16].

Potential Disease Complications

Extensor tendon injury can result in permanent loss of finger extension, primarily due to adhesion formation or joint contracture. Painful degeneration of the affected joints can occur if normal motion is not restored.

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, renal, and cardiovascular systems. Acute tendon ruptures as a result of aggressive therapy necessitate reoperation, which may include tendon grafting. Therapy programs that are not aggressive enough often result in reduced range of motion and strength. Surgical complications include infection, adhesion formation, and advanced joint degeneration.