Section 3 Management of diabetes

Type 1 diabetes – initiating therapy

Insulin regimens

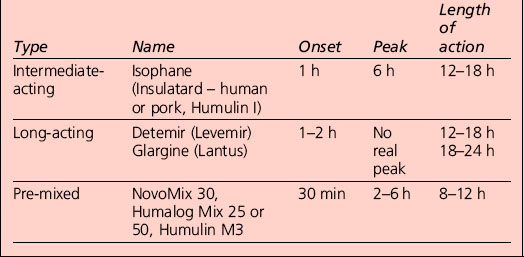

Appropriate combinations of the above insulins can be tailored to the individual; a certain element of this will be trial and error, but close liaison with the health-care provider usually results in the right regime for that person (Table 3.1). The pre-mixed insulins are a popular starting regimen, and the timing of onset, peak and duration of action will depend on the component parts.

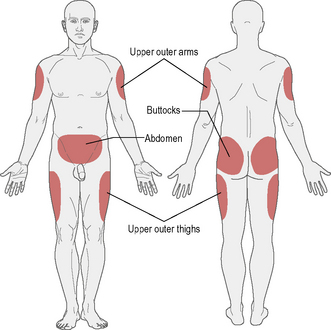

Insulin injection sites

The recommended sites for insulin injection are shown in Figure 3.1. Injection should be given into a pinched-up skin fold using thumb, index and middle finger, taking up the skin and leaving the muscle behind. This will avoid intramuscular injection. Too shallow an injection will be delivered intradermally, and can be painful.

• Insulin absorption is fastest in the abdomen and slowest in the arms and buttocks. Short-acting insulin is best given into the abdomen, and long-acting insulin into the thigh or arm; however, this can be varied according to the most practical site available.

• Most importantly, the injection sites should be ‘rotated’: if the abdomen is the site used most often then rotating around different points regularly is a good idea. This should avoid lipohypertrophy (an accumulation of fat under the skin), which occurs if the same injection site is used repeatedly. If this occurs, it can be unsightly and increases the variability of insulin absorption.

• If a person rotates from limb to limb, it is good idea to try to stick to a schedule whereby the same area is injected at the same time of day, for example morning injection in the abdomen, teatime injection in the leg.

• Insulin absorption may also be accelerated by exercising that part of the body (e.g. injecting legs and then jogging/running).

Different insulin delivery systems

Needle and syringe

This is the traditional method of delivery. The following steps are recommended:

1. Clean the rubber stopper of the bottle with alcohol. If intermediate-acting or long-acting insulin is being used (cloudy insulins), mix by rolling or rotating the bottle.

2. Open the syringe to the number of units that is needed so that there is air to this point in the syringe.

3. Turn the insulin bottle upside down and inject the stopper with the needle.

4. Push the air inside and withdraw the insulin dose required.

5. Give the syringe a few taps with your finger to get the bubbles to the top, and push the bubbles back into the bottle.

6. Pinch up the area of skin to be injected.

7. Insert the needle at a right angle to the skin and push it in; then push down the plunger to administer the insulin.

Jet injection device

• Allergy. Local allergic reactions are uncommon with modern insulin preparations; reactions to diluent or preservatives are sometimes thought to be of relevance; a change of brand may help, but many cases resolve spontaneously. Transient tender nodules developing at the injection site are suggestive; generalized allergic reactions are exceedingly uncommon. Testing kits are available from insulin manufacturers. Major insulin resistance due to high titres of anti-insulin antibodies that cause antigen–antibody complexes is very uncommon; corticosteroids may be useful.

• Lipohypertrophy. Localized areas of lipohypertrophy, although comfortable to inject into, are thought to cause erratic absorption of insulin from the site. The hypertrophy is attributed to the trophic effects of insulin on fat metabolism. Avoidance of the area may lead to regression; liposuction has been used.

• Lipoatrophy. This has become rare since the introduction of highly purified, and more recently human sequence, insulins. It may be improved by the injection of highly purified soluble insulin around the edge of the lesion.

Altering insulin doses

• Alter one insulin dose at a time.

• Alter the appropriate insulin based on knowledge of the pharmacokinetics of the insulin preparations being used. For example, on twice-daily mixtures of short- and medium-acting insulin:

• A relatively small change (2–4 units) is generally safe; larger changes may be indicated in some instances, but care should be taken to avoid inducing hypoglycaemia. Such small alterations are not always appropriate; the magnitude of the increase or decrease should reflect the overall insulin dose. For example, for a patient stabilized on a daily dose of 40 units, a change of 4 units is 10% of the total; for a patient on 100 units, a proportionately similar change would be 10 units. Moreover, when insulin has just been initiated, tiny daily increases in dose may be too cautious. However, experience is required in judging whether larger increases are indicated.

• If recurrent hypoglycaemia occurs at the higher dose, the patient should drop back to the previous dose.

• Remember that increasing the dose of a pre-mixed insulin preparation will increase both the short- and the longer-acting components.

• Be prepared for discrepancies between theory based on insulin pharmacokinetics and the realities of clinical practice.

Unwanted effects of insulin therapy

Severe insulin resistance

The definition is arbitrary. When daily insulin doses (in excess of 200 units) were needed to control glycaemia, it was considered to reflect severe insulin resistance; this is now largely of historical interest. The concept of insulin resistance is discussed in Section 1.

• Severe insulin resistance syndromes. Specific causes of severe insulin resistance, congenital or acquired, are very rare.

• Brittle diabetes. Whether this entity exists is regarded as contentious by some. Apparently high insulin requirements with swings in control are a feature of some patients with idiopathic brittle diabetes.

• Hormonal stress response to intercurrent illness. Transient insulin resistance may arise in the course of intercurrent illnesses (e.g. sepsis); temporary increases in insulin doses, sometimes necessitating a change to intravenous or multiple subcutaneous doses of short-acting insulin, are required. Insulin may be required during the course of such an illness in patients previously well maintained on oral antidiabetic agents; this will usually be undertaken in the hospital setting. With resolution of the acute episode, reintroduction of oral therapy may be possible.

• Anti-insulin antibodies. The role of acquired anti-insulin antibodies, once thought to be an important mechanism of insulin resistance, has faded with modern, less antigenic, insulin preparations.

• Obesity. Clinical insulin resistance is confined largely to patients with type 2 diabetes whose obesity and associated insulin resistance limits attainment of glycaemic targets despite large doses of insulin. However, type 1 patients can become obese and develop insulin resistance – possible ‘double diabetes’.

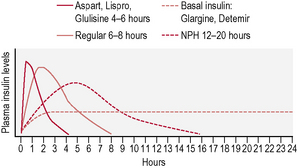

Insulin regimens

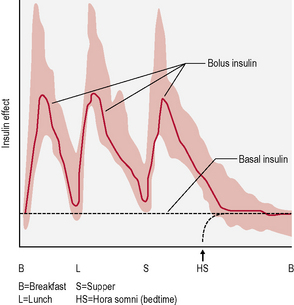

This is the schedule of insulin that a person will decide upon with their health-care professional, and is based on the type of diabetes, physical needs and lifestyle (in particular eating patterns and activity). The variables include type of insulin, timing and dose (Fig. 3.2). There are many regimens, but the most common examples are:

• Insulin added to oral medication. This combination is worthwhile in those with type 2 diabetes where the fasting blood glucose begins to rise despite maximum oral medication. It most often means a dose of long-acting insulin at bedtime.

• Twice-daily insulin. This is either two doses of an intermediate-acting insulin or two doses of a mixed insulin to give more control over postprandial increases in blood glucose (Fig. 3.3). The latter is often used in type 1 diabetes when the individual wants to avoid taking insulin at work/school at lunchtime.

• Basal-bolus insulin. This is essentially intensive insulin therapy and is discussed below (Fig. 3.4).

Adverse effects of insulin therapy

• Hypoglycaemia. This is the most common disadvantage of insulin therapy and occurs when the amount of insulin taken is too much for the amount of food ingested, exercise undertaken or starting level of blood sugar. It may also occur as a consequence of excess alcohol intake (see Section 4).

• Weight gain. When insulin is started, a person will begin to retain fat; this is normal to some extent. People will find they are unable to eat as much as they did previously without putting on weight and therefore they should beware of overeating. Also, eating snacks to avoid hypoglycaemia should be limited as much as possible. It is usually better to reduce the insulin dose rather than eating to justify it.

• Insulin allergy. This is now extremely rare due to the use of human insulin.

Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion therapy

Some important points to know about pumps

• They do not measure blood sugar and so the pump still needs to be directed by blood sugar measurements with a meter and dose adjustments.

• There are two basic rates of delivery: the basal rate, which is a slow, continuous trickle when a person is not eating, and the bolus rate, which is a much higher flow rate delivered when a meal is about to be eaten.

• Much guidance is required, especially at the start, from the diabetes specialist nurse and/or doctor, in addition to a dietitian.

• National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend that pumps be considered in those where other insulin regimes have ‘failed’ – where it is not possible to reduce HbA1c to less than 7.5% without causing ‘disabling hypoglycaemia’. Pumps should also be considered only for patients who are committed to gaining the considerable expertise and competence that the effective use of a pump requires.

Disadvantages of pumps

• Skin infections can occur as the infusion set is left in situ for a few days.

• Ketoacidosis can occur rapidly if the pump disconnects, as short-acting insulin is the only form given.

• Blood glucose must be measured frequently to adjust the pump for best control.

• They are expensive (more than £2500, with annual costs of about £1200).

• Limited availability of pumps supplied from the National Health Service.

Type 2 diabetes – initiating therapy

Oral hypoglycaemic agents

Classification

Oral antidiabetic drugs may usefully be classified by their actions as being either:

This distinction, which reflects differences in chemistry and hence mode of action, is clinically relevant. Drugs in the latter category do not usually cause hypoglycaemia when used as monotherapy. It should be noted that other drugs, not used primarily as antidiabetic agents, may also lower plasma glucose concentrations (Table 3.2). The latter agents may potentiate the glucose-lowering effects of other drugs.

Table 3.2 Hypoglycaemic and antihyperglycaemic drugs used to treat type 2 diabetes

| Hypoglycaemic drugs | Antihyperglycaemic drugs |

|---|---|

| Sulphonylureas | Biguanides |

| Repaglinide | α-Glucosidase inhibitors |

| Thiazolidinediones | |

| GLP-1 analogues/DPP-4 inhibitors |

GLP, glucagon-like peptide; DPP, dipeptidyl peptidase.

Use of insulin in type 2 diabetes

The waning of response to oral agents reflects the gradual attrition of endogenous insulin secretion that characterizes type 2 diabetes. Dietary compliance is also likely to be important in some cases. Non-obese patients masquerading as type 2 patients may have sufficient β-cell reserve at diagnosis to have a satisfactory response to oral agents. A proportion of these middle-aged to elderly patients have autoimmune markers associated with type 1 diabetes. These patients represent a subgroup called latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA; see p. 59).

Contraindications to oral antidiabetic agents

There are a number of acute or temporary clinical situations where oral antidiabetic agents are contraindicated in patients with type 2 diabetes; insulin therapy should be instituted in these circumstances (Table 3.3). After resolution or recovery, a satisfactory therapeutic response may be attained following the reintroduction of oral agents.

| Clinical indication | Rationale for insulin therapy |

|---|---|

| Major acute intercurrent illness (e.g. septicaemia, MI) | Deterioration in metabolic control with sulphonylureas and risk of lactic acidosis with biguanides |

| Pregnancy | Inadequate metabolic control with oral antidiabetic agents; safety concerns about medication other than metformin and glibenclamide |

| Surgery | Risk of perioperative hypoglycaemia (especially with long-acting sulphonylureas); risk of lactic acidosis with biguanides |

| Acute major metabolic decompensation (DKA or HONK/HHS) | Absolute or marked relative insulin deficiency in concert with insulin resistance mandates insulin therapy |

DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; HONK, hyperosmolar non-ketotic coma; HHS, hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state; MI, myocardial infarction.

Biguanides

Mode of action

Effects on fatty acid metabolism may also contribute to the improvement in glycaemia through decreased activity of the glucose–fatty acid (Randle) cycle in muscle and liver; these substrates compete for uptake and oxidation (see Section 1, p. 45). Through increasing insulin sensitivity, metformin has effects on some of the components of the metabolic syndrome. In addition, the beneficial effects of metformin therapy in overweight patients previously demonstrated are not explained solely by improvement in glycaemia. In particular, metformin appears to have a cardioprotective role in overweight type 2 patients.

Adverse effects

Metformin is a safe and well tolerated drug.

Lactate metabolism

Metformin therapy does not lead to an increase in lactic acid levels and there is no evidence that it increases the risk of developing lactic acidosis (see p. 161). However, metformin should be avoided in clinical conditions in which lactate production is increased (e.g. cardiopulmonary disease) or hepatic clearance impaired (e.g. alcohol abuse).

Nateglinide

Pharmacokinetics

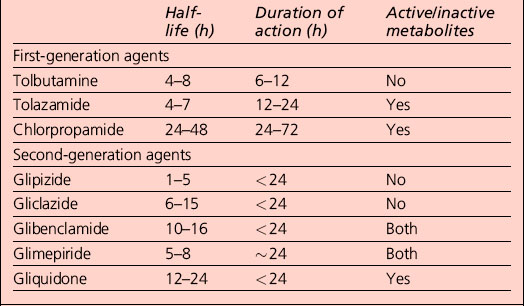

Repaglinide is rapidly absorbed, has a short plasma half-life (less than 60 min), is hepatically metabolized and is excreted principally (90%) in the bile. It is designed for use only when a meal is consumed; if a meal is skipped, no drug is taken. The tablet should ideally be taken 30 min before the meal. This mealtime dosing allows for more flexibility than is possible with once- or twice-daily sulphonylureas, which have much longer duration of action (Table 3.4). Thus, repaglinide can be viewed as a prandial glucose regulator.

Thiazolidinediones

Mode of action

The thiazolidinediones lower glucose by two main mechanisms:

Incretins

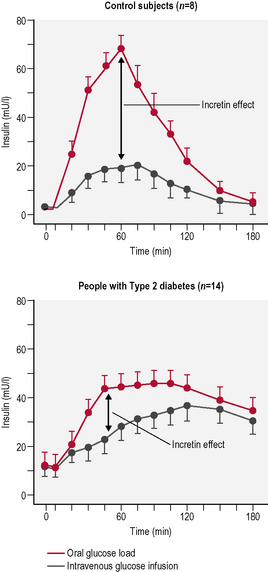

It has been known for many years that glucose administered orally gives rise to much higher insulin levels than glucose given intravenously despite similar or even higher plasma glucose levels. This increase is due to the release of intestinal humoral substances. Incretins are a group of gastrointestinal hormones that cause this increase in the amount of insulin released from the β-cells of the islets of Langerhans. This increase occurs before blood glucose levels are increased. These intestinal humoral substances also slow the rate of absorption of nutrients into the bloodstream by reducing gastric emptying, and in many patients directly reduce food intake by central effects on satiety. They also inhibit glucagon release from the α-cells of the islets of Langerhans. The two main candidate molecules that fulfil criteria for the incretin effect are glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP). Both GLP-1 and GIP are inactivated rapidly by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP)-4. Type 2 patients have a blunted incretin response, and infusion studies have shown that GIP is ineffective in type 2 diabetes (Fig. 3.5).

Glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists

Glycaemic control

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (gliptins)

Glycaemic monitoring

Blood glucose monitoring

Practical limitations to self-testing include:

• inadequate manual dexterity (e.g. deforming rheumatoid arthritis or advanced neuropathy; post-stroke)

When to test?

In addition, a test at 0200–0300 hours, although inconvenient, may be important for patients in whom nocturnal hypoglycaemia (which may be asymptomatic) is suspected. Tests before and after exercise can be used to guide reductions in insulin dose or need for additional carbohydrate (see p. 74).

Self-monitoring in people with type 2 diabetes

• those at increased risk of hypoglycaemia

• those experiencing acute illness

• those undergoing significant changes in pharmacotherapy of fasting, for example during Ramadan

• those with unstable or poor glycaemic control (HbA1c > 8.0% (64 mmol/mol))

Principles of education in diabetes

Education in adults with diabetes

• have a person-centred, structured curriculum that is theory-driven and evidence-based, resource-effective, has supporting materials, and is written down

• be delivered by trained educators who have an understanding of education theory appropriate to the age and needs of the programme learners, and are trained and competent in the delivery of the principles and content of the programme they are offering, including the use of different teaching media

• provide the necessary resources to support the educators, and that the educators are properly trained and given time to develop and maintain their skills

• have specific aims and learning objectives and should support development of self-management attitudes, beliefs, knowledge and skills for the learner, their family and carers

• be reliable, valid, relevant and comprehensive

• be flexible enough to suit the needs of the individual, for example including the assessment of individual learning needs, and to cope with diversity, for example meeting the cultural, linguistic, cognitive and literacy needs in the locality

• offer group education as the preferred option, but with an alternative of equal standard for a person unable or unwilling to participate in group education

• be familiar to all members of the diabetes health-care team and integrated with the rest of the care pathway, and that people with diabetes and their carers have the opportunity to contribute to the design and provision of local programmes

• be quality-assured and reviewed by trained, competent, independent assessors who assess it against key criteria to ensure sustained consistency

• control of vascular risk factors, including blood glucose, blood lipids and blood pressure

• management of diabetes-associated complications, if and when they develop

Organization of diabetes care

Diabetes centres

• diagnosis and assessment of new patients

• long-term follow-up (usually for selected groups where adequate arrangements exist for the provision or sharing of follow-up with primary care teams; see below)

• continuing education of patients and staff

• education for other groups (e.g. community-based nurses)

• screening for chronic complications (see Section 5)

• provision of specialist medical care for special groups (e.g. pre-pregnancy and during pregnancy, young patients)

• assessment and treatment of erectile dysfunction (see p. 188)

Staff

Staffing of the diabetes centre will typically include:

• consultant diabetologist – specialist training in diabetes; team leader

• specialist diabetes nurse – most health districts in the UK have at least one, and often more. Responsibilities include education and provision of day-to-day practical direction and support for patients, both in hospital and in the community, organization of staff training, development and implementation of local policies, commissioning of new equipment, introduction and evaluation of new treatments and technologies, research and audit. The diabetes specialist nurse should be well versed in counselling and education skills. Nurses may elect to concentrate on special groups such as children.

In addition, the services of other specialists will also be required as necessary:

Inpatient care

Diabetic patients account for a disproportionate amount of hospital inpatient activity. Hospital admission is now rarely required for initiation of insulin therapy, but is necessary for the management of acute metabolic emergencies (see Section 4). Hospitalization is also frequently required for the management of serious acute microvascular and macrovascular complications, notably foot ulceration (see p. 188). Other common conditions such as unstable coronary heart disease and cardiac failure usually necessitate emergency or elective admission.

Surgery is required more often by diabetic patients (see above); close liaison between the surgical and diabetes services is obviously desirable. Written protocols for the management of diabetes during surgery or MI (see p. 207), DKA (see p. 148) or labour (see p. 250) should be agreed upon, implemented, audited and refined. This should be a continual process aiming not just to maintain but also to raise standards of care.

• pre-assessment planning for elective admissions is undertaken and implemented

• every person with diabetes has an assessment and care plan for their hospital stay that is regularly updated as appropriate

• coordination and administration of medications and food in a timely manner

• access to food and snacks appropriate for maintaining good diabetes management

• protocols are in place for the timely prevention and management of hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia, including self-management of these complications where appropriate

• people are supported to optimize blood glucose control during their hospital stay

• information about the inpatient stay is provided to people with diabetes

• people with diabetes have access to the specialist diabetes team and education

• effective multidisciplinary communication between staff

• a discharge and follow-up plan is developed for each individual.

Supported self-management of diabetes

People with diabetes wishing to self-manage:

• should be supported to do so where appropriate

• should have access to their self-monitoring equipment

• should have access to education, including information about how to access a structured education programme.

In order to support the delivery of the above, there needs to be:

• the implementation of diabetes training for all medical and nursing staff to ensure health-care professionals are equipped with the necessary competencies

• the development and implementation of protocols and/or systems to cover: communication, ongoing referral, surgery, prevention, and the timely and effective management of acute complications

• the implementation of audit and the commissioning of models of care shown to be effective.

Diabetes inpatient specialist nurse (disn)

• act as a resource for expert advice and training for nursing staff, medical staff and other health-care professionals

• provide a highly specialized diabetes management and education service to patients referred within secondary care

• lead and contribute to strategic issues relating to diabetes care

• carry out audit and research work in connection with all aspects of diabetes care and participate in quality assurance programmes

• communicate with all areas, both professional and voluntary

• work as part of the diabetes team to provide a multidisciplinary service input with extended knowledge and skills in diabetes management.

Diabetes in primary care

• miniclinics – performed in general practice but based on hospital clinics

• integrated care systems – wherein patient management is shared between the primary and secondary sectors to a greater or lesser degree.