Legal Aspects Affecting the Administration of Medications

Objectives

1. List the names of major federal laws about drugs and drug use.

3. Describe the differences between authority, responsibility, and accountability.

4. List rules of states and agencies that affect how nurses give drugs.

5. Explain how the nurse is responsible for controlled substances.

6. List what information is included in a medication order or prescription.

7. Define and give examples of the four different types of medication orders.

Key Terms

controlled substances (kŏn-TRŌLD SŬB-stăn-sĕz, p. 17)

delegation (dĕl-ĕ-GĀ-shŭn, p. 21)

engineering controls (ĕn-jĭn-ĒR-ĭng, p. 29)

legal responsibility (LĒ-gŭl, p. 21)

nurse practice act (p. 21)

over-the-counter (OTC) medications (mĕd-ĭ-KĀ-shŭnz, p. 17)

physical dependence (FĬZ-ĭ-kăl, p. 18)

prescription, or legend, drugs (prĭ-SKRĬP-shŭn, p. 17)

problem-oriented medical record (POMR) (p. 23)

professional responsibility (p. 21)

psychologic dependence (sĭ-kō-LŎJ-ĭk, p. 18)

scheduled drugs (SKĔD-jūld, p. 17)

Pharmacology and Regulations

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Edmunds/LPN/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Edmunds/LPN/

Nurses who give medications have three levels of rules they must follow:

Federal Laws

Laws passed by Congress try to make medications as safe as possible for patients to take and to make sure that the drug does what it claims to do (effectiveness). Congress created the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to monitor or watch the testing, approval, and marketing of new drugs. These regulations are very strict and so U.S. drugs are some of the most pure and protected drugs in the world. Many laws have been passed to control drugs that might easily be abused and are dangerous. Table 3-1 lists some of the major federal drug laws that have been passed.

Table 3-1

Summary of Major Federal Drug Legislation

| TITLE OF LEGISLATION | YEAR | DESCRIPTION OF LEGISLATION |

| Harrison Narcotic Act | 1914 | Limited the indiscriminate use of addictive drugs. Regulated the importation, manufacture, sale, and use of opium, cocaine, and their compounds and derivatives. Amended many times and finally repealed and replaced by the Controlled Substances Act in 1970. |

| Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act | 1938 | Authorized the Food and Drug Administration of the Department of Health and Human Services to determine the safety of drugs before marketing, to determine labeling specifications, and to ensure that advertising claims are met. |

| Durham-Humphrey Amendment | 1951 | Restricts the number of prescriptions that can be refilled. |

| Kefauver-Harris Amendments | 1962 | Provides greater control and surveillance of clinical testing and distribution of investigational drugs. A product must be proven to be both safe and effective before it may be released for sale. |

| Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act (Controlled Substances Act) | 1970 | Composite law that repealed almost 50 other laws. Designed to improve the administration and regulation of manufacturing, distributing, and dispensing of controlled drugs. The Drug Enforcement Administration was created to enforce the Controlled Substances Act, gather intelligence, train investigators, and conduct research on potentially dangerous drugs and drug abuse. |

| Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act | 2001 | Requires hospitals to have programs to prevent needlestick injuries, document them when they occur, and purchase safe equipment regardless of cost. |

Federal laws created three drug categories in the United States:

2. Prescription, or legend, drugs such as antibiotics and oral contraceptives

3. Over-the-counter (OTC) medications, which patients may buy without a prescription

Controlled Substances

Most regulations are written for controlled substances, because they are often abused both by patients and people using them illegally. After the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 classed these medications into five “schedules,” they became known as scheduled drugs. The degree of control, the record keeping required, the order forms, and other regulations are different for each of these five classes. Table 3-2 describes the five drug schedules, with examples of medications in each category. Sometimes the drugs are moved from one class to another if it becomes clear they are being abused.

Table 3-2

| SCHEDULE | POTENTIAL FOR ABUSE | COMMENTS AND EXAMPLES |

| I | High | No currently accepted medical use in the United States. Lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision. |

| Examples: hashish, heroin, lysergic acid diethylamide, marijuana, peyote, 2,5-demethoxy-4-methamphetamine. | ||

| II | High | Abuse potential that may lead to severe psychologic or physical dependence. |

| Examples: amphetamines, meperidine, methadone, methaqualone, morphine, pentobarbital, oxycodone (Percocet), secobarbital. | ||

| III | High, but less than I or II | Abuse potential that may lead to moderate or low physical dependence or high psychologic dependence. |

| Examples: glutethimide, aspirin with codeine (Empirin with codeine), aspirin with butalbital and caffeine (Fiorinal), methyprylon, paregoric, acetaminophen with codeine (Tylenol with codeine). | ||

| IV | Low compared with III | Abuse potential that may lead to limited physical or psychologic dependence. |

| Examples: lorazepam (Ativan), diazepam (Valium). | ||

| V | Low compared with IV | Abuse potential that may lead to limited physical or psychologic dependence. |

| Examples: diphenoxylate with atropine sulfate (Lomotil), guaifenesin with codeine sulfate antitussives. |

Federal and state laws make it a crime for anyone to have controlled substances without a prescription. Each state has a practice act that lists which health care providers may dispense or write prescriptions for controlled substances. Pharmacists usually dispense the medications; physicians, dentists, osteopaths, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and sometimes nurse midwives may write prescriptions. Licensed practical nurses (LPNs) or licensed vocational nurses (LVNs) may give controlled substances to a patient only under the direction of a health care provider who is licensed to administer or prescribe these drugs. Mediation aides or technicians are also used by some hospitals to administer drugs. Student nurses work under the delegated authority of the registered nurse (RN). The RN is responsible for any errors that might be made by these individuals.

Nurses may not have controlled substances in their possession unless one of the following conditions is met:

• The nurse is giving them to the patient for whom they are ordered.

• The nurse is the person in charge of the supply of medications of a ward or department.

• The nurse is the patient for whom a physician has prescribed the medication.

LPNs/LVNs work in some of the most sophisticated areas of medicine with high technology as well as some of the least sophisticated areas where they may be the health care worker with the most training and relatively no technology available. They must be prepared to practice within this large range of settings. Each state and health care agency has rules that cover the ordering, receiving, storing, and record keeping of controlled substances. Narcotics are a scheduled drug and they must all be counted every shift. Records must be kept for every dose administered. Agency policy will decide which nurses will be held responsible for handing over the control of these medications from one shift to the next and for how medications will be counted and checked. All controlled substances ordered for a patient but not used during their hospital stay go back to the pharmacy when the patient is discharged.

Nurses may not borrow medicine ordered for one patient to use for another patient or for themselves. In a time when drug abuse is so common, the nurse who has responsibility for the controlled substances must remain alert. Abuse is not limited to patients. Some health care professionals may not be able to resist such a large supply of medication and will seek to hide their theft of a patient’s medication. Things that should arouse suspicion might include a pattern in which medication is frequently “dropped” or “spilled” or records that show a patient got large or frequent doses of medications on certain shifts but the patient reports no pain relief. In these cases, perhaps the patients are not really getting their medication.

The rules that govern controlled substances are very clear and very strict. Breaking the rules is very serious. If it is found that the nurse has violated the Controlled Substance laws, the nurse may be punished by a fine, a prison sentence, or both. Nurses with proven drug abuse problems will lose their license to practice and may have a hard time getting it back. Nurses who do not report their suspicion that other nurses may be breaking the rules risk their own jobs. In most states, the state nursing association has a program to help nurses who have drug abuse or other problems that affect their ability to carry out their nursing duties.

Prescription, or Legend, Drugs

The FDA has decided that many drugs are dangerous and their use must be carefully controlled. Access to these drugs is provided by a few health care professionals (physicians, dentists, and nurse practitioners). This control is through a written prescription or order that must be written before the drug may be given. Prescription drugs make up most of the medications the nurse gives to patients in a hospital. Prescription drugs are carefully tested before they are put on the market. The drugs have been shown to be safe and effective. However, even though much may be known about a particular medication, each patient is different and may have a somewhat different reaction to the drug. Pediatric patients, older adult patients, and critically ill patients may be weak and more likely to have problems taking a drug. The nurse must be alert and watch for signs that the drug is working the way it should, as well as for adverse reactions that may develop. Because the patient often gets several drugs at the same time, the interaction among the drugs may make it hard to tell how each drug affects the patient. Although a lot of research about drugs has been done, many drugs are not FDA approved as safe and effective for children or pregnant women. Geriatric patients are at high risk for problems with prescriptions drugs, because they may not take the drug properly because of poor eyesight, memory, or coordination; they may take many drugs that interact with each other; or they may have chronic diseases that interfere with how the drug works.

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Acts of 1989, 1990, and 1991 placed further controls on drugs for Medicare or older patients. More and more, insurance or government groups who pay for drugs limit the types and numbers of drugs that may be ordered to those on a preferred drug list. The preferred drug list may require the use of cheaper generic drugs to control costs because new or brand-name drugs usually cost more.

Over-the-Counter Medications

The FDA has also found that many drugs are quite safe and do not need a prescription. These drugs may easily be purchased at a drugstore or pharmacy. These drugs often come in a low dosage, and they have low risk for abuse. Warning labels and special information supplied with these drugs make them safe for the average buyer. They are used to treat many common human illnesses: colds, allergies, headaches, burns, constipation, upset stomach, and so on. These drugs are often the first thing patients try before they go to the doctor. Although OTC medications are widely available, they are not without risk. Like all drugs, some may produce adverse effects in some patients. They may also have “hidden” chemicals such as caffeine or stimulants that may produce problems if taken with other drugs. Confusion by parents over the correct dosage of common cold preparations led to many accidental overdoses in children, so these drugs have been removed from the market. Other cold products that contain dextromethorphan and might be abused are now stored behind the pharmacy counter. Talking to patients about the use of OTC medications is very important for patients who are already taking many prescription drugs. New federal laws for labeling of these products will make more information available about the drug and make it easier for the patient to understand.

OTC drugs are also given in the hospital for minor problems patients may have. Although these medications do not require a prescription for purchase, a physician’s order is required before they may be given in the hospital. In fact, without an order, hospitalized patients cannot take even their own OTC medicines brought along to the hospital. This policy is necessary for safety reasons. If patients could take their own medicines in addition to those medicines given by hospital staff, it could result in an overdose of medicine.

In recent years, many people have become interested in herbal products. Research shows that most people will try an herbal product at some time in their lives. Health food stores, grocery stores, and pharmacies all carry some of these products. Some people take these herbal products instead of their prescription drugs, and some use them along with their prescription drugs. Although research may someday find that these products are safe and effective, at present these herbal products are not regulated, standardized, or tested for safety and effectiveness. Because the federal government considers herbal products to be nutritional supplements rather than drugs, there are no regulations to control how they are made. There is no way to know if one leaf that is ground up and made into a pill will work the same as another leaf that is ground up. Also, the nurse cannot easily tell how much of the herbal product is in each pill, or even if each pill in a bottle contains the same amount of the product. Because research on these products is only beginning, little is known about side effects, and it is hard to tell if some of them actually have the intended effect. Finally, adverse effects may occur when a patient takes herbal products and prescription drugs at the same time.

Because of the high cost of drugs in the United States, some patients try to buy drugs from other countries where they both cost less and are easier to buy—usually in Mexico or Canada. Although low-cost drugs can be good for patients, in some cases there is a risk the drugs may not be pure, may not be the drugs patients believe they are buying, or may even be dangerous. Drugs that originate in China or India often look like real drugs but may be fake. It is hard to know if the drugs sold in other countries or over the Internet are real. At this time, buying drugs in other countries and bringing them into the United States is not legal. The FDA is opposed to patients being able to get drugs that cannot be proven to meet high U.S. standards.

Because U.S. drug companies often sell their drugs to other countries at a cheaper rate than in the United States, there is growing interest by many groups in buying some of these drugs, particularly from Canada. Many nurses and patients in Canada or along the U.S.-Canadian border must deal with Canadian drug regulations and classifications that are different from those in the United States; some specific information is provided in the next section.

Canadian Drug Legislation

The Canadian Health Protection Branch of the Department of National Health and Welfare is like our FDA of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This branch is responsible for the administration and enforcement of federal legislation such as the Food and Drugs Act, the Proprietary or Patent Medicine Act, and the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. These acts, together with provincial acts and regulations that cover the sale of poisons and drugs and those that cover the health care professions, are designed to protect the Canadian consumer from health hazards; misleading ads about drugs, cosmetics, and devices; and impure food and drugs. The Canadian Food and Drugs Act divides drugs into various categories. Regulations covering the various categories or schedules of drugs differ from those in the United States. There are three major classes of drugs under the Food and Drugs Act: nonprescription drugs, prescription drugs, and restricted drugs.

The laws within the Canadian Food and Drugs Act allow the government to withdraw from the market drugs found to be toxic. New drugs put on the market must be shown in human clinical studies to be effective and safe to the satisfaction of the manufacturer and the government.*

The Proprietary or Patent Medicine Act provides for a class of products that may be sold to the general public by anyone. The drug formula is not found in the official drug manuals or printed on the label. The formulas for all such proprietary (trade secret) nonpharmacologic drugs must be registered and have a license under the Proprietary or Patent Medicine Act. The nurse needs to be aware of this act in the case of possible drug interactions.

The Canadian Controlled Drugs and Substances Act covers the possession, sale, manufacture, production, and distribution of narcotics in Canada. Only authorized persons may have narcotics in their possession. All persons authorized to be in possession of a narcotic must keep a record of the names and quantities of all narcotics dispensed, and they must ensure the safekeeping of all narcotics. The law covering this act is enforced by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Nurses are in violation of this act if they are guilty of illegal possession of narcotics.

OTC drugs are regulated in Canada by the Canadian Food and Drugs Act. These drugs can be purchased without a prescription, but there are rules about the package, label, and dispensing of the drug. The nurse needs to be aware of the risks these medications have and watch for possible adverse effects and interactions with other drugs. OTC drugs available in Canada differ from those available in the United States.

State Law and Health Care Agency Policies

Although many regulations about giving medications come from federal laws, the details about who may give medications are set by each state. This authority is spelled out for nurses in the nurse practice act of each state, which describes who can be called a nurse and what they can and cannot do. These rules vary from state to state and have changed over the years to reflect the increased responsibility many nurses have for giving medications. The authority to administer medications is clearly specified for LPNs/LVNs, RNs, and nurse practitioners in the state nurse practice act. Giving medicines is a task reserved for those nurses who are named by law to administer medications and who can document their educational preparation to do so. These nurses must also show they are willing to accept professional responsibility for administering drugs correctly, ethically, and to the best of their ability. This means they also accept legal responsibility for good judgment and their actions while doing these professional tasks.

Differences in practice from state to state make it essential that each nurse learn what is legal with regard to medications and make sure they and others follow all the rules. Because people in our society tend to move from state to state, nurses must know exactly what is in the nurse practice act of the state where they are now working. Using computers for ordering drugs, record keeping, and even advising patients (telemedicine) makes it possible for doctors and nurses in one state to be involved in health care for patients in different states. Today, nurses frequently move between jobs, and some states recognize the nursing license of another state through an agreement called the Nurse Licensure Compact. There is a growing list of states that participate in the Compact (available at www.ncsbn.org). Because of the differences among states in what is allowed, a national nursing license may one day be granted.

State rules about nursing practice often list the basic or minimum standards of practice. Therefore, agency or institutional policies and guidelines may be more specific or restrictive than state nurse practice acts. Agency employers should provide:

1. Written policy statements regarding:

• educational preparation of nurses administering medications

• agency or institutional policies nurses must follow

2. Orientation to particular policies, procedures, and record-keeping rules

When the nurse accepts a job, it implies he or she is willing to obey the policies or procedures of that institution. Sometimes the nurse must meet very formal rules in order to give medications. It may be an agency’s policy to require employment for a certain period, completion of special orientation and training sessions, and passing a probation period before permission is given to administer medications. Even when the nurse may have the legal authority to give medications, they can do so only when the nurse has a valid medication order signed by an authorized prescriber.

All nurses have legal responsibility for what they do. As stated before, what they are and are not permitted to do is listed in the nurse practice act of the state. Some RNs with advanced training like nurse practitioners have expanded their clinical practice to include tasks that only doctors did in the past, and LPNs/LVNs in some settings perform tasks that were once done only by RNs. These trends are likely to continue because of efforts to cut overall health care costs. The changes in who does what are legally linked to the term delegation.

Delegation is when the responsibility for doing a task is passed from one person to another, but the accountability for what happens, or the outcome, remains with the original person. The person who delegates a task to someone else must have the authority to do so, and the person to whom it is delegated must also have the authority to perform that task. RNs now often delegate many of their tasks, including giving medications, to an LPN/LVN. For example, if the LPN/LVN has the educational preparation, clinical experience, and agency authority to give medications, then the RN may delegate this task to her or him. The RN still retains accountability for making sure that the LPN/LVN is able to perform the task correctly, whereas the LPN/LVN is responsible for what she or he does. In some settings, an LPN/LVN may direct the work of other LPNs/LVNs or unlicensed personnel such as nurse’s aides. The LPN/LVN in this situation remains accountable and responsible for assigning tasks to the nurse’s aide or other LPN/LVN, and the aide or other LPN/LVN is responsible for the care that is actually delivered. This principle is also true for the student nurse. The student in an RN or LPN/LVN program is held to the same standard of practice as the graduate. The student works under delegated responsibility from the RN, but the RN maintains accountability.

Although there are many formal regulations for giving medications, there are also some requirements of medication administration that are less formal and rely on the judgment and knowledge of the nurse. The agency expects the nurse to carry out the steps of the nursing process and, in fact, holds the nurse responsible for good assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation of the patient when medication is given. The nurse will be held responsible for failure to perform any of these steps well.

The nursing process is a helpful system to be used when giving medications. There is a professional and an implied legal requirement that nurses use this process. The nurse must understand information about the patient: symptoms, diagnosis, and why the medication is to be given. The nurse also learns other information about the patient’s past medical history, allergies, risk factors, and reaction to medications or any information that contraindicates (forbids) giving the drug. Nurses learn about the medication itself: the dosage, the route of administration, the expected response, and adverse reactions. Knowledge about other medications is also mandatory, because nurses must watch for possible drug interactions. The nurses understands and follows the medication procedure: how, when, and where the medication is to be given and equipment or special techniques needed. The nurse also acts to monitor the patient’s response after the medication is given, record the information about the drug that was given, and report promptly to the RN or physician any unexpected results. Finally, the nurse uses every chance they have to teach the patient and the family the information they need to know for continued and safe administration of this medication.

Patient Charts

The patient’s chart, whether it is paper or electronic, is a legal record. It is the major source of information about the patient and the care received while in the hospital. It provides a central place where members of the health care team record information about the patient and all treatment. The physician or other health care provider describes the patient’s condition on admission, determines the diagnosis, and provides orders to identify or resolve the patient’s problems. The nurse records the assessment of the patient’s condition, the implementation of basic nursing procedures, the patient’s response, and the progress in completing the diagnostic and therapeutic plans. While the patient might request a copy of the chart, the chart belongs to the hospital. It is not the property of the patient, the nurse, or the physician. It is the legal record of the patient’s stay in the hospital. It is kept after the patient has been discharged, and it is often used for billing, insurance, and auditing activities; in medical or nursing research; and to provide information if the patient should be admitted again. In cases of court action or lawsuits, the chart may be used by lawyers as evidence. It is especially important that nurses write meaningful and accurate information in a complete and readable manner. Using electronic medical records and data entry systems helps nurses do this.

Health care is delivered in many different places in this country and around the world. Some agencies and countries have few resources, and care is very limited. Others have the latest computers and treatment systems. Throughout the nurses career, they will probably work in places with different resources. For example, a nurse may work in an agency that has the latest computerized medication system installed in each patient’s room or in a nursing home that has no medication recording system. If the nurse has the chance to practice in another country, they might find that although the tasks nurses perform for patients are often the same, there may be different ways of carrying out nursing activities. Nurses learn the basics about nursing activities related to giving medications, and then adjust that knowledge to the setting in which they practice. Some of the basics include the following:

• The nurse must record the drug administration information. Every agency has its own order sheets and recording forms for the patient’s chart. Agency policy will tell you what information is to be placed in each section. Although there are a variety of forms, certain things are traditionally part of every chart. These parts are listed in Box 3-1. There is growing use of computers and electronic record keeping. Many hospitals take computers to the bedside, scan all medication barcodes as they are given to the patient, and the information is recorded electronically in the patient’s record. These systems help prevent errors.

Kardex

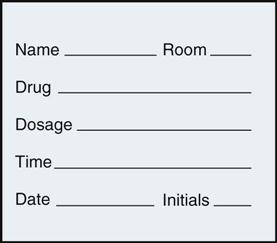

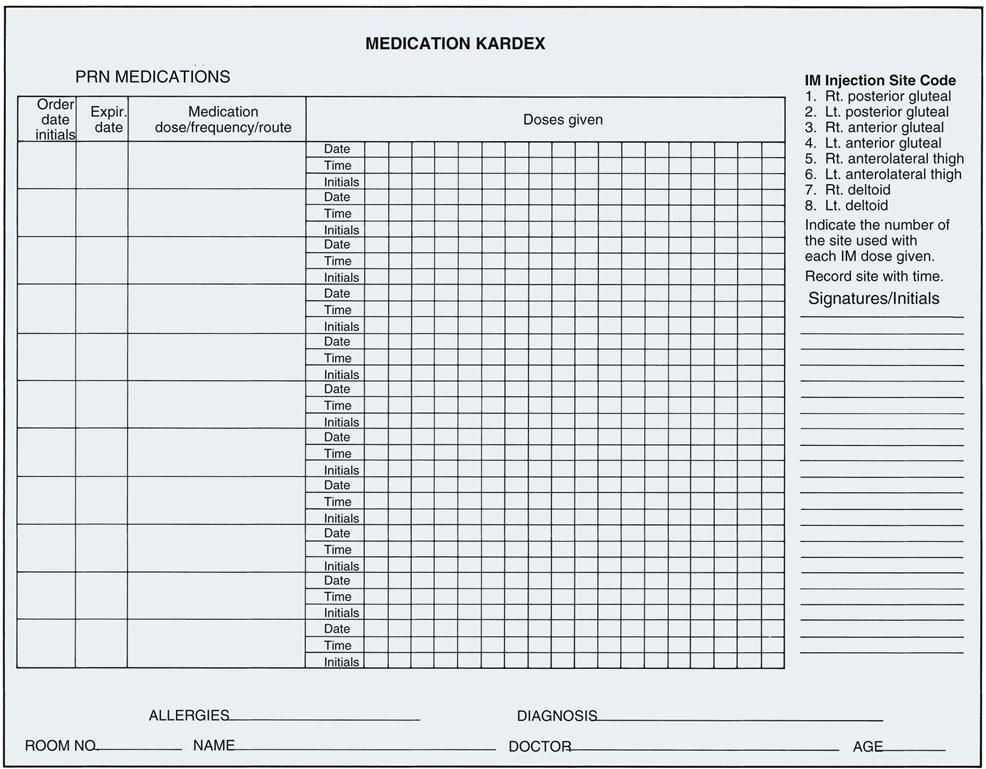

The Kardex is a flip-file card system used for many years that has important information from the patient summary form and the physician’s orders. It is regularly updated and changed to reflect current orders. This format keeps important information about the patient easily available for all team members. In the past, all tests, medications, and treatment orders were listed here, along with the nursing care plan. Some agencies still require use of a medication card for each drug to be given to the patient (Figure 3-1). More commonly, when a unit-dose system is used, individual medication cards are not needed, because all medications are listed in the Kardex or medication profile sheet (Figure 3-2). Some computerized dispensing systems create their own separate patient medication forms as drugs are dispensed. The Kardex card is thrown away when the patient is discharged. It is not a legal document and serves no further purpose. Some settings may not use this Kardex system but will use an electronic order entry system and charting system. This prevents illegible prescriber handwriting. Many systems are designed to indicate if the dose ordered is out of the acceptable range, would interact with another ordered medicine, or other dosing errors. LPNs/LVNs may find that they often work in health care settings that continue to use the older, low-cost information systems, so they need to be comfortable in either setting.

Drug Distribution Systems

Each agency has its own way of ordering and administering medications. There are four commonly used systems to distribute medications to the nurse:

These four systems are described in Box 3-2.

Both the unit-dose system and the computerized or automated dispensing systems currently in use in the U.S. may link a barcode on the medication to a barcode on the patient to help reduce medication errors. Scanning the barcode helps get the right drug to the right patient.

Narcotics Control Systems

Both federal and state laws, as well as agency policies, are very clear about how controlled substances are handled in the hospital. These procedures are nearly identical from hospital to hospital. The primary goal of all regulations and policies is to verify and account for all controlled substances. When controlled substances, particularly narcotics, are ordered from the pharmacy, they come in single-dose unit or prefilled syringes and are attached to a special inventory sheet. The nurse receiving the order from the pharmacy must inspect the medication and return to the pharmacy a signed record stating that all the medication ordered was received and that it was in acceptable condition. As each medication is used, it must be accounted for on the inventory sheet by the nurse giving the medication.

The use of narcotics is carefully monitored on the hospital unit. Medication is stored in a special locked cabinet. The key to this cabinet is carried by the head nurse or by a medication nurse. This individual has the legal responsibility for the use and recording of all the narcotics during that shift, whether or not they personally give the medications to the patients. There are automated medication dispensing systems. They include narcotics plus also stock medicines that nurses withdraw by password or fingerprint instead of a key system.

When controlled substances are ordered for a patient, the nurse responsible for giving the medication first checks the order and verifies the dosage and the last time the medication was given before obtaining the key to the cabinet. The nurse must sign out all medications administered during the shift. The inventory report form is completed before the drug is removed from the cabinet. This report may be written or a patient barcode inserted and should state the patient’s name, date, drug, dosage, and the signature of the nurse giving the medication. The medication given should be noted in the patient’s chart, and there should also be a follow-up note about the patient’s response to the medication. If a dose is ordered that is smaller than that provided (so that some medication must be discarded), or if the medication is accidentally dropped, contaminated, spilled, or otherwise made unusable and unreturnable, two nurses must sign the inventory report and describe the situation. Institutional policy may require additional actions.

At the end of each shift, the responsibility for all narcotic controlled substances and the key to the controlled substances cabinet is transferred to another nurse from the new shift. The contents of the locked cabinet are counted together by one nurse from each shift. The numbers of each ampule, tablet, and prefilled syringe in the cabinet must match the numbers listed on the inventory report form. Sealed packages are kept sealed. Opened packages of medications must each be inspected and counted. Prefilled syringes must be examined to make sure they all have the same color, the same fluid levels, and the same amounts of air within them. Both nurses must sign the inventory report, officially stating that the records and inventory are accurate at that time.

Occasionally, the inventory and the written report do not agree. Any errors in the number of remaining doses and the number listed in the inventory report must be explained. All nurses having access to the key must be asked about medication they have given. Steps must be retraced to see if someone forgot to record any medication. Patient charts might also be checked to see if medication was given that was not signed for on the inventory report. If errors in the report cannot be found, both the pharmacy and the nursing service office must be notified. If the error is large, the hospital administrator and security police are usually contacted.

You can see that the nurse with the key has a lot of responsibility in watching over the controlled drugs on the nursing unit. This nurse is usually a very mature person, often the head nurse or a nurse who has been with the hospital for some time and has proven he or she can be trusted. It is the duty of this nurse to give the key only to other nurses authorized to administer controlled substances. Keys are never given to physicians or any other health care worker. (Sometimes a physician will want to give the medication, but the nurse should get the medication and sign the inventory report.) The nurse in charge of narcotic controlled substances should be able to monitor all activity with the controlled drugs on a daily basis so that if a pattern develops, changes are easily seen. On a hospital unit that has many patients coming from surgery, use of narcotics for these patients will be high soon after surgery but should taper off within 2 to 3 days. If a patient continues to need large or frequent doses or needs narcotics for longer than other patients with the same condition, the nurse in charge of these drugs should be suspicious. Any activity that causes concern relating to controlled substances should be noted by the head nurse.

The Drug Order

Both state law and agency policy require that all medications given in hospitals must be ordered by licensed health care providers acting within their areas of professional training. This generally restricts prescriptive authority (the authority to write an order or prescription for medication) to physicians, dentists, and, in some states, nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, nurse anesthetists, and physician assistants who work for the hospital or clinic. Prescriptions for a hospitalized patient are written on the order form in the patient’s chart or recorded in the electronic record, which may be seen by the pharmacy. Sometimes the order can be faxed, sent electronically, or is on a tear-off sheet sent directly to the pharmacy to get the medication. Other times the order must be transcribed, or rewritten, by the nurse or unit secretary onto a special pharmacy order form.

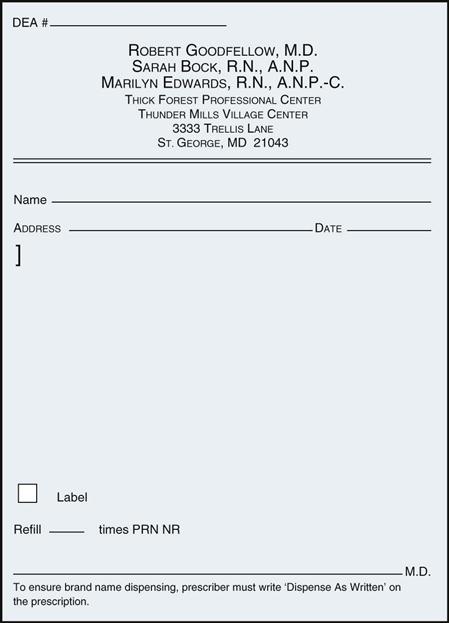

Prescriptions for patients leaving the hospital are written on regular prescription pads and taken to a pharmacy or drugstore to get the medication (Figure 3-3). Clinics or offices may work with pharmacies that will fill prescriptions for their patients. Every time a patient has a prescription filled, they should receive information about the product and how they should take it.

Whether the prescription is for hospitalized or nonhospitalized patients, the order contains the same information: the patient’s full name, date, name of drug, route of administration, dose, frequency, duration, and signature of prescriber. Additional details about how to give the drug may also be written: “Take with meals,” “Avoid milk products with this drug,” “Do not refill,” “Please label.” Pharmacies require the patient’s age and address on the prescription. This information may help the pharmacist ensure the right drug dosage for the patient (e.g., a child or older adult) or verify the patient’s identity.

In emergencies, or when the physician is not in the hospital, the physician might give the nurse either a verbal order or an order over the telephone. All agencies have policies about these types of orders. The hospital decides who may take these orders—usually the RN. The nurse taking the order is responsible for writing the order on the order form in the chart, including both the name of the nurse and the name of the doctor. Many institutions also require that a note be written to indicate that the order was read back to the physician for validation. The physician must then cosign this order, usually within 24 hours, for the order to be valid.

Medication orders may be classified into one of four types of orders:

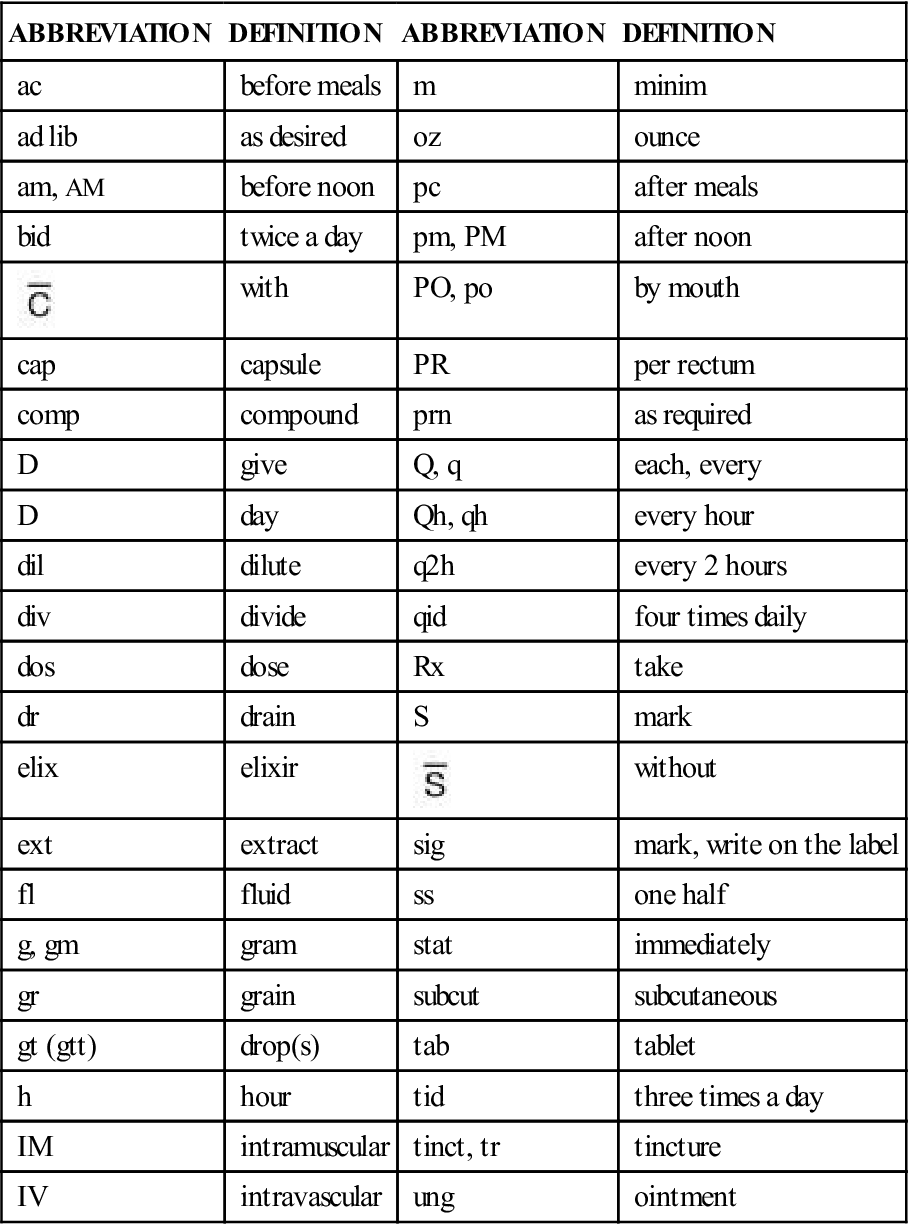

The agency’s policy clearly defines each of these types of orders and how they are carried out. Some agencies have also created a “now” order classification. A now order is different than a stat order in that the nurse has 1.5 hours to give the medication, unlike the stat order that must be given within minutes. The general definition of each type of order and examples of each are presented in Table 3-3. Table 3-4 lists common abbreviations used in pharmacology, which the nurse must memorize.

![]() Table 3-3

Table 3-3

| DESCRIPTION | EXAMPLE |

| Standing Order | |

| Indicates that the drug is to be administered until discontinued or for a certain number of doses; hospital policy dictates that most standing orders expire after a certain number of days. A renewal order must be written by the physician before the drug may be continued. | “Amoxicillin 500 mg PO TID 10 days.” “Ibuprofen 600 mg PO q6h.” |

| Stat Order | |

| One-time order to be given immediately. | “Lidocaine 50 mg IV push stat.” |

| Single Order | |

| One-time order to be given at specified time. | “Meperidine 100 mg IM 8 am preoperatively.” |

| PRN Order | |

| Given as needed based on nurse’s judgment of safety and patient need. | “Docusate 100 mg PO at bedtime prn constipation.” |

| NOW Order | |

| To be given within an hour and a half. | “Lomotil II NOW for diarrhea.” |

Table 3-4

Common Abbreviations Used in Pharmacology

| ABBREVIATION | DEFINITION | ABBREVIATION | DEFINITION |

| ac | before meals | m | minim |

| ad lib | as desired | oz | ounce |

| am, AM | before noon | pc | after meals |

| bid | twice a day | pm, PM | after noon |

|

with | PO, po | by mouth |

| cap | capsule | PR | per rectum |

| comp | compound | prn | as required |

| D | give | Q, q | each, every |

| D | day | Qh, qh | every hour |

| dil | dilute | q2h | every 2 hours |

| div | divide | qid | four times daily |

| dos | dose | Rx | take |

| dr | drain | S | mark |

| elix | elixir |  |

without |

| ext | extract | sig | mark, write on the label |

| fl | fluid | ss | one half |

| g, gm | gram | stat | immediately |

| gr | grain | subcut | subcutaneous |

| gt (gtt) | drop(s) | tab | tablet |

| h | hour | tid | three times a day |

| IM | intramuscular | tinct, tr | tincture |

| IV | intravascular | ung | ointment |

In an effort to cut down on medication errors, The Joint Commission (TJC), the agency that accredits or approves hospitals, has discouraged health care workers from using any abbreviations that might lead to confusion. That means that abbreviations that were used in the past (such as “hs” for nighttime, “cc” for cubic centimeter, and “QD” and “QOD” for daily and every other day) are no longer used in hospitals that wish to maintain their accreditation. Please go to the back of the text for abbreviations that must be included on each accredited organization’s “Do Not Use” list.

Medication Errors

Despite the best rules and procedures, medication errors occur in busy hospitals. Policies and procedures differ about what to do when a medication error is made. However, there are some guidelines that everyone accepts. When it is discovered that an error has been made, the nurse should immediately check the patient. Does the error pose a risk to the patient’s condition (for example, giving too large a dose of insulin)? If so, the physician should be notified promptly, and any orders the physician gives must be followed. Every effort should be made to watch the patient’s condition through measuring vital signs, drawing blood for tests, or any other method ordered by the physician. The nurse should also notify her nursing supervisor, record in the patient’s chart exactly what happened, and fill out any other agency required reports. Whether the error is a problem for the nurse is often related to what happens to the patient. How and why the error was made and how it might be avoided in the future will be determined. If the nurse was careless or negligent, she may be held legally liable for any adverse consequences to the patient. Although almost every nurse has made one medication error, repeated errors will not be ignored. Research must be done in institutions to determine whether the mistakes made in that institution are most commonly due to a “system error,” a unique mistake, a failure to follow the “six-rights” in giving a drug, or a deliberate wrong-doing.

In a very important Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report (“To Err is Human,” IOM, 2000) about the number of errors made in medical care, estimates suggest that adverse events, which include medical errors, occur in 3% to 4% of patients. The IOM report and other studies estimate that the costs of medical errors in the United States, including lost income, disability, and need for additional health care, may be between $17 billion and $136.8 billion or more annually. These costs come from a variety of drug-related problems, including patient compliance issues and medical or medication errors. Unfortunately, estimates suggest that more than half of the adverse medical events each year are because of medical errors that could be prevented.

Because of this report, most agencies have tightened up ways to report and follow up on medication errors and some improvement has been confirmed in the most recent studies. Nurses should make every effort to know and follow the most recent agency policies to prevent errors.

Legislation To Protect Health Care Workers

Because patients have infections that may place nurses at risk, care must be taken to protect nurses and other health care workers. One of the most dangerous things nurses do is to recap the needle of a syringe that has been used in the injection of a sick patient. Recapping needles frequently leads to nurses accidentally sticking themselves. In 2001, the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act became federal law. The object of the law is to prevent exposure in hospitals to bloodborne pathogens such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus. The law requires hospitals to follow the guidelines in the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. As part of this standard, health care institutions must have a written plan spelling out their efforts to cut the risk of needlestick injuries. In addition, employers are required to provide the safest equipment available, regardless of cost. Such equipment includes needleless products or those with engineering controls, which are built-in safety features to reduce risk. If a needlestick injury does occur, it is to be carefully recorded in a needlestick injury log. The exposure control plan, selection of safety products, and needlestick injury log must be reviewed at least every year. Many states have chosen to pass “tougher” laws, but at a minimum, every state law must meet the OSHA standard.