are no longer lower than the OECD average, and are increasing (AIHW 2006; The OECD Health Project 2004).

Relative to the United States (US), the United Kingdom (UK), Canada and New Zealand (NZ) (countries most commonly used by Australian analysts for comparison) Australia has the best overall health outcomes, and exceeds the US and ranks reasonably closely with the others on equity. Australia’s health system is less costly than that of the US, but is substantially more expensive than those of the UK and NZ. For Australians covered by health insurance, access to doctors and emergency departments is better than in the other countries, except NZ, and access to elective surgery is better than in the other countries, except the US.

Some of these results reflect, in part, the balance struck in the Australian system between choice and equity, with incentives to supplement access via Medicare with private health insurance cover. The US does not have universal coverage but relies heavily on private insurance arrangements, while the UK, NZ and Canada do not have incentives for supplementary private insurance.

Australia’s most serious health policy problem is Indigenous health. Indigenous people’s life expectancy is around 17 years less than for other Australians, a larger gap than that between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in the US, Canada and NZ (ABS and AIHW 2005, AIHW 2006).

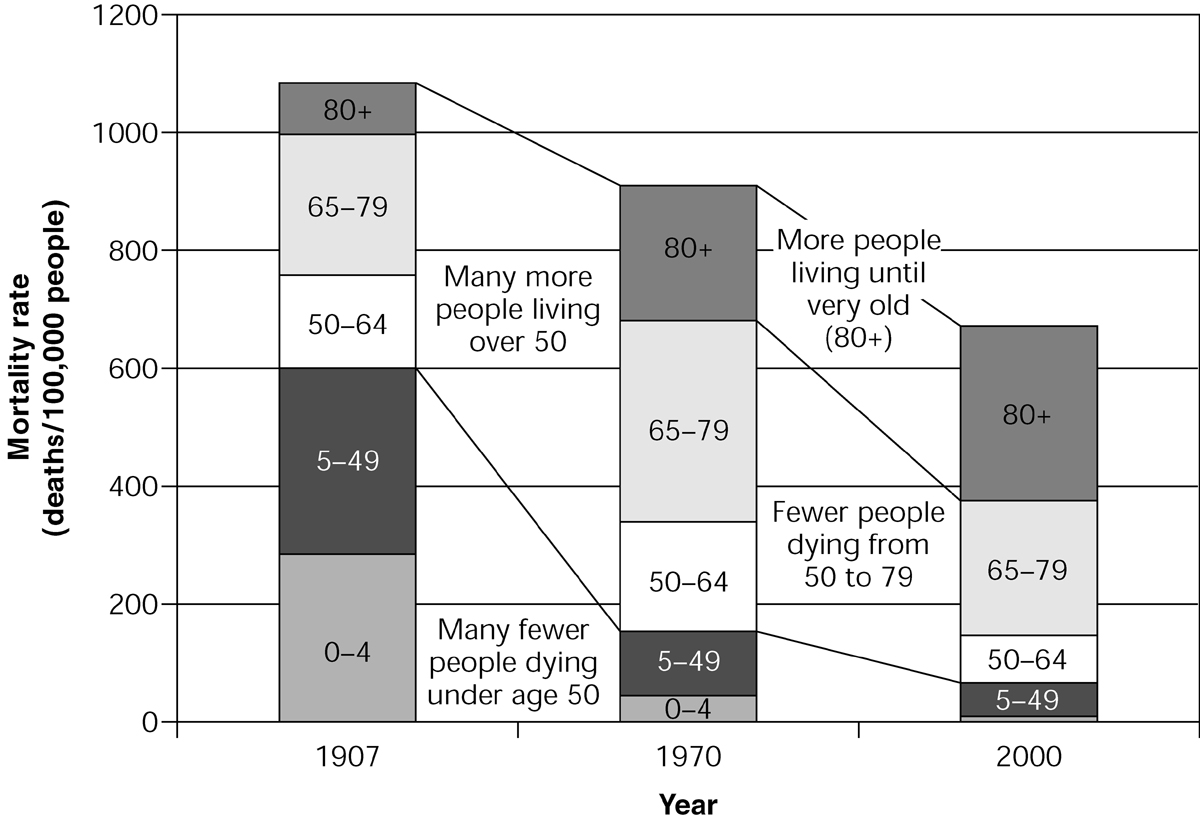

Second to Indigenous health, the biggest challenge for Australian policy makers is to address the consequences of major successes: that Australians are living a lot longer today, and are not dying as rapidly as they used to after being diagnosed with, for example, heart disease or cancer. Figure 3.1 illustrates historical changes in Australian mortality rates.

Figure 3.1 Changes in Australian mortality rates 1907–2000 Source: AIHW 2005

The increase in life expectancy in Australia from 1907 to 1970 reflected successes in reducing child mortality and mortality overall, so that many more people reached the age of 50, but the increase in life expectancy since 1970 has been dominated by gains in ensuring that those who reach age 50 live a lot longer on average after that point. Life expectancy is still increasing at around 3 or 4 months every year. One of the consequences of this is the increased number of frail aged people. There are also many more people who have survived the onset of heart disease or cancer or other diseases, but require some ongoing care regime to ensure they can live with reasonable independence and quality of life.

The AIHW has estimated that about 80% of the burden of disease in Australia is now related to chronic disease (AIHW 1999, 2004a). A central question now is how well the Australian health system performs in managing chronic disease and the needs of the increasing numbers of the very frail aged.

There is evidence that improvements could be made (AIHW 2004a, 2004b). There is a high rate of potentially avoidable hospitalisations for chronic conditions. The care of the frail elderly who need some hospital care could be better managed; too many of them go to hospital too often and there are too many elderly people in hospitals awaiting residential aged care. Step-down and rehabilitative care has been substantially cut in the past decade or so. Despite incentives for general practitioners to coordinate care plans for the chronically ill, the take-up of the incentive has until recently been weak, and there is patchy support for those patients needing allied healthcare and advice. The increasing incidence of obesity and diabetes, in particular, suggest we are investing too little in preventive health strategies.

A more integrated approach to healthcare is needed. Australia is not performing as well as it should on care for the chronically ill and is ranked at the bottom of the five nations surveyed by the Commonwealth Fund (2005). The structure of the Australian health system is almost certainly contributing to this poor performance. The structure involves a series of distinct programs related to particular providers and products: the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) reimbursing patients for visits to doctors; the Australian Health Care Agreements, under which states fund public hospital care for public patients; the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) subsidising prescription medicines; the Residential Aged Care program subsidises care in nursing homes and hostels; and the Health and Community Care (HACC) program (and the Australian government’s aged care packages) subsidising community care services for people living at home. There are also the federal government’s incentives, including the private health insurance rebate, for private health insurance for hospital and related specialist medical care services. The problems associated with this program structure are exacerbated by the different sources of funding, adding to incentives to sharpen the boundaries.

Apart from obstructing the patient orientation essential for appropriate care, in particular of the frail aged and those with chronic illnesses, the structure constrains the overall efficiency of the system, and contributes to its rising costs. Australia has an international reputation for expertise in applying cost-effectiveness requirements for listing and pricing pharmaceuticals; this has been expanded to medical services. There have also been successes in using casemix-based purchasing to drive efficiencies in the hospital sector, though there has been some reluctance to extend the use of casemix and other sophisticated purchasing techniques and competition. Australia’s complex funding arrangements for public and private hospital care also produces an uneven playing field and inappropriate incentives for hospitals and private insurers.

Perhaps the most significant contributor to inefficiency is not the lack of technical efficiency within particular program areas, but allocative inefficiency where the balance of funding across programs (including public health in particular) is not giving best value, and the inability to shift resources between programs at local or regional levels. Allocative efficiency has attracted considerable attention overseas since a study comparing the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) and Kaiser Permanente’s system in California (Feachem et al. 2002). The study suggested the NHS might perform better if it allocated more of its resources to primary care and information technology. However, it is likely that the problem in Australia is greater than in the UK, because of a stronger demarcation of programs, particularly through having different funders with incentives for cost shifting and blame-shifting, and the UK’s greater experience with integrated purchasing mechanisms such as general practitioner (GP) fundholding and primary care trusts.

Cost shifting and blame-shifting also have direct costs. Claims of substantial bureaucratic costs involved in overlapping activities between the Commonwealth and the states and territories (Dwyer 2004) are greatly exaggerated: the whole Commonwealth health department’s operating costs in 2005–06 amounted to only $569 million. But a great deal of political and bureaucratic attention is given to this game-playing instead of seeking to improve the effectiveness of health services.

In summary, the key structural problems in Australia’s health system are:

- the lack of patient-oriented care that crosses service boundaries easily with funds following patients, particularly those with chronic diseases, the frail aged and Indigenous people

- allocative inefficiency, with the allocation between different types of care, and between care and prevention, not always achieving the best health outcomes possible, and with obstacles to shifting resources for individuals or communities to allow different mixes reflecting different needs.

These structural problems have been reinforced by poor use of information technology, which could support continuity of care, better identification of people at risk, greater safety and more patient control. They have also been exacerbated by the poor use of purchasing and competition, with a reluctance to use sophisticated approaches to ensure best access to effective services at reasonable cost, and an ‘uneven playing field’ in the area where competition is most encouraged.

REFORMING THE SYSTEM

There have been many sensible, incremental reforms over the past 15 years to address structural problems in the Australian health system.

Perhaps most importantly, there has been a gradual strengthening of primary care, which is central to a more integrated approach. This has come through establishing GP divisions and the progressive extension and complementing of MBS items to incorporate funding for practice support, incentives for preventive health, such as immunisation and cancer screening, and care coordination and planning. Most recently, funding has been allocated through general practice of ancillary health services for particular groups of patients, such as the mentally ill. GP funding is now essentially through blended payments, including both fee-for-service and funding for the patient population.

Increased incentives have been offered to practice in rural areas, where healthcare services are less plentiful. Some flexible funding has been provided for community health services, either directly by the Commonwealth to GPs and GP divisions, or in cooperation with states and territories; for example, for multi-purpose health service centres.

Additional funding has also been provided to Indigenous communities for primary healthcare, recognising their lack of direct access to MBS and PBS. The coordinated care trials in particular achieved substantial improvements in services to participating communities, and easier access to PBS funds for remote communities has also contributed to improvements in healthcare access (Department of Health and Ageing 2001, 2006a).

Increased emphasis on community aged care services and more flexibility in aged care funding through ‘ageing in place’ has also improved the responsiveness of the system to older patient needs and preferences (Department of Health and Ageing 2004).

Steps have also been taken to improve and link information support (see also Ch 11). Legislative prohibition of linking the MBS and PBS has been removed; pharmacists have (with government support) developed better patient records that support both safer use of medicines and cost reduction for both patients and government; GPs are also increasingly using electronic patient record systems after a low take-up of government support for some years; and hospital discharge information is more frequently passed on to GPs, even if rarely done electronically. The Health Connect initiative, aimed to establish the standards necessary to allow easier transfer of patient data and to establish a national system of electronic health records, is slowly making progress.

There have also been improvements in cost controls using forms of purchaser–provider arrangements. Some states have developed sophisticated approaches to hospital financing using casemix, following federal government investment in the model. The Australian government has entered into increasingly robust agreements with the medical profession on pathology and radiology funding, even experimenting with a competitive approach to the funding of MRI services in country areas. The Australian government’s use of cost effectiveness in listing and pricing PBS items has also incorporated more sophisticated approaches in complex cases, such as the use of price-volume agreements to share risks. And cost effectiveness is slowly being extended to the MBS.

With the exception of the Veterans’ Affairs portfolio, where the Australian government, as the single funder, has facilitated a substantial review of the balance of care services for veterans, mechanisms to encourage better allocational efficiency have not so far been particularly successful. The 1998 Australian Health Care Agreements (AHCA) included a provision to ‘measure and share’ options for shifting resources between the federal government and a state or territory where it was evident there would be efficiency and effectiveness gains. After 5 years, progress was made in only one state on one initiative: the provision of drugs on discharge from hospitals. There is little evidence of much progress since, despite regular statements of cooperation.

In other areas, the continued division of financial responsibilities encouraged action that was neither in the interests of patients nor in the interests of overall efficiency. The number of rehabilitation beds in state and territory hospitals declined, notwithstanding the ageing population and a substantial increase in admissions by older people. Australian hospitals also continue to exhibit a different approach to emergency departments than do their overseas counterparts, with few having an area offering appointments for people with less urgent medical needs. Instead, such patients are triaged along with urgent cases, and may end up waiting hours for attention.

The division of responsibilities also continues to encourage politically inspired initiatives that duplicate and complicate service provision. The HACC program, jointly funded by the Australian and state or territory governments, has proven to be difficult to reform into a standardised package of services based on assessed need, and in recent years the Australian government has introduced and extended its own program of aged care packages.

Nonetheless, there have been good incremental reforms, and more are still emerging. The 2006 initiatives for mental healthcare added further to the role and capacity of primary care services, responding to the yawning gap in mental health services that developed after the well-intentioned deinstitutionalisation policies of the 1980s (Department of Health and Ageing 2006b). Changes to the regulation of private health insurance should also improve competition between funds, and encourage them to consider out-of-hospital care where that would be more efficient and effective (Abbott & Minchin 2006).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR POLICY DEVELOPMENT

Given the effort required and risks involved in systemic reform, it is understandable that most attention continues to be placed on incremental reform options.

There is a risk, however, that incremental reform without a clear sense of direction will be mere ‘ad hocery’. To avoid this risk, incremental measures need to meet some broad tests:

- coherence with a national policy framework that incorporates principles of universal access to quality services, a patient-oriented approach that facilitates continuity of care, efficient service delivery with a considerable degree of patient choice and provider competition, and a focus on safety, effectiveness and cost effectiveness

- progress towards, or at least not moving further away from, integrated service provision

- contribution to making systemic reform (sometime in the future) easier, not harder.

- progress towards, or at least not moving further away from, integrated service provision

In addition, initiatives need always to deliver tangible improvements in services to patients or tangible gains in efficiency and cost effectiveness (and preferably both), in order to attract the support of the key stakeholders in the system: patients and professional service providers. Incremental measures that would clearly meet the tests identified above are set out in Box 3.1.

BOX 3.1 INCREMENTAL MEASURES TO REFORM THE HEALTH SYSTEM

- Renegotiating the Australian Health Care Agreements (AHCA) to promote more forcefully the agenda of cooperation at the program boundaries where reallocation of resources would improve care effectiveness and efficiency (e.g. rehabilitative care, discharge services, outpatient services and emergency departments), and to require all states and territories to apply casemix processes to funding hospitals.

- Restructuring responsibilities for out-of-hospital aged care services, so that the national government would have full and direct financial responsibility, the states and territories having full and direct responsibility for people under 65 with disabilities; the Australian government would then have the opportunity to pursue the reform agendas it has been foreshadowing for some years in the areas of community services based on assessments and high-care residential services allowing more choice.

- Commencing to build a regional infrastructure based on state- and territory-defined regions, starting with information through regional health reports prepared independently by the AIHW on the health of the relevant population, the utilisation of health services, and the total government spending on the regional population; this to be complemented by relating current state, territory and federal government regional planning arrangements (e.g. for hospitals and aged care services, and by GP divisions) to each other, drawing upon shared information, including the AIHW reports.

- Establishing a new Australian government primary care funding program available to regions with low levels of government health expenditure, for highly flexible use to strengthen access to primary care services. This might include new incentives to attract GPs, and funding nurse practitioners and allied health professionals. The funds could be made available through GP divisions or other regional arrangements determined by the Australian government.

- A long-term program to expand funding for Indigenous communities on a broadly similar basis: increasing primary care funding to the average level across Australia, adjusted for the higher costs of care delivery in remote and regional areas.

- Restructuring responsibilities for out-of-hospital aged care services, so that the national government would have full and direct financial responsibility, the states and territories having full and direct responsibility for people under 65 with disabilities; the Australian government would then have the opportunity to pursue the reform agendas it has been foreshadowing for some years in the areas of community services based on assessments and high-care residential services allowing more choice.

Such measures would start to build a clearer framework for managing and delivering health services. While there would be some financial costs involved, the funding would be well targeted, and a start would be made to strengthen purchaser–provider arrangements and to develop a regional funding system, opening up options for future cost controls that promote allocational efficiency rather than inefficiency in resource allocation.

The creation of a single funder or a single purchaser drawing from pooled funds would address the fundamental problems of fragmented services not focused on patients, and of allocational inefficiency. The four main options for such a system include:

d. the Scotton model, or ‘managed competition’ model, with total government funding to be channelled through private health insurance funds by way of ‘vouchers’ equal to each individual’s risk-related premium which the individual may pass to the fund of their choice, the fund then having full responsibility as funder and/or purchaser of all their health and aged care services (Scotton 2002).

The first option has the advantage in the Australian context of building on the trend over the last 50 years of increasing federal government involvement in funding and purchasing health and aged care services: the Australian government is now responsible for over two-thirds of government funding. It is certainly feasible, if state officials with the expertise in purchasing hospital services transferred to the Australian government. But it would require a lot of effort to establish new administrative systems, and the GST agreement with the states would need to be renegotiated.

The second option could follow the Canadian model, with national principles being set by the Australian government under a revenue sharing agreement, and states having purchasing responsibility through their regional networks. It would, however, involve reversing our history, returning to the states the more than two-thirds of the public spending on health now funded by the Australian government, and a delicate negotiation of the national government’s remaining policy responsibilities and the states’ authority, for example, to vary MBS, PBS and private health insurance funding arrangements and to manage regulatory arrangements.

The third option appears on first examination to be less radical than these two. But it would involve continuing financial negotiations and continuing political and bureaucratic exchanges because of shared accountabilities. Such processes might be no less difficult than the negotiations under either of the first two options, and there would always be the risk of a return to blame-shifting whenever agreement could not be reached. Political paralysis would be a real possibility, and/or an excessive reliance on officials to settle debates about resource allocation within and between regions.

The final option, managed competition, has the theoretical elegance of both a single purchaser arranging integrated services in a universal system, and greater choice and competition. The jury is out, however, as to whether the model is feasible and whether competing funds would deliver more efficiency gains than is possible from just competing providers. The international evidence suggests little if any additional gains (see, for example, Musgrove 1996). Most importantly, as Scotton himself has made clear, this option would only be feasible if first the Australian government became the single government funder of the system.

In Australian realpolitik, the only feasible options for systemic change appear to be options (a) and (c): either the Australian government taking over full financial responsibility, or some cooperative pooling arrangement. In the longer term, the latter option could prove too cumbersome to manage, and might also leave unresolved the complex problems surrounding private health insurance (see further below).

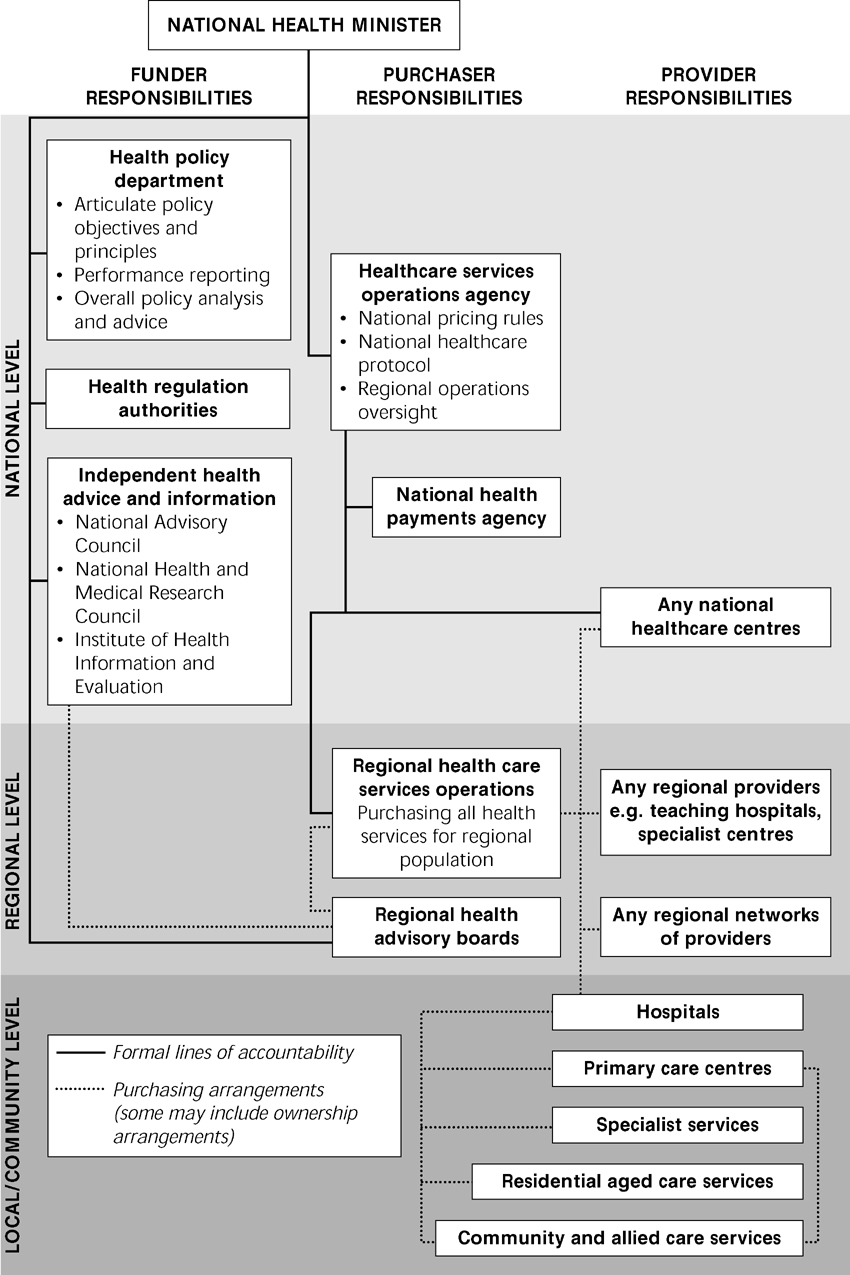

Figure 3.2 illustrates how option (a) might operate, with the national government as funder and purchaser, and with the capacity for local and regional flexibility.

Figure 3.2 Possible operational arrangements under Commonwealth single-funder model (option a)

There is considerable room for debate about the details of how this option might be managed, particularly around governance arrangements that provide for responsiveness to local and regional communities.

While the simplest version of the option, with clearest accountability, is for the Australian government to be both funder and purchaser, a possible variation is for the states and territories to have a role not only in providing services such as public hospital care, but also in purchasing arrangements. Under such a variation, the states and territories could play a major role in regional planning and purchasing subject to detailed policy guidance by the federal government. Regional purchasing would, in any case, be constrained by detailed national arrangements for the MBS and the PBS, and by national policy in other areas such as casemix prices and aged care subsidies. Indeed, regional budgets could not be subject to firm caps, nor to firm guarantees: cost control would be improved by regional arrangements, but could not over-ride national policies such as the demand-driven nature of the MBS, the PBS and safety net arrangements. Arguably, with this level of policy detail being set from the top, it would be possible to allow involvement of states and territories and other players in the detailed planning and purchasing arrangements at regional and local levels.

So, for example, some aspects of the pooling option (option (c), could for some time be applied to option (a), at least while the Australian government’s new regional administrative arrangements were being put into place. It might also be possible to pursue option (a) selectively for a period with those states and territories most willing to pursue systemic reform.

How option (a) might be implemented is set out in Box 3.2.

BOX 3.2 A SEQUENCE FOR THE NATIONAL GOVERNMENT ASSUMING FULL FUNDING AND PURCHASING RESPONSIBILITIES FOR ALL PUBLICLY FUNDED HEALTH AND AGED CARE SERVICES

- The national government to offer an in principle agreement with (some or all) of the states and territories based on a sufficiently detailed proposition about the financial transfers involved.

- A dedicated project team under the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) with associated bilateral task forces, to track all government expenditure to each region, commence joint planning for the initial handover and commence ‘due diligence’ work.

- The initial handover might focus first on the national government sharing management of state primary care services (assisted by the availability of additional Australian government funds), and also taking over direct responsibility for all non-acute aged care services; and in establishing a skeleton regional structure.

- Subsequently, the full transfer stage would involve both the transfer of funds and the transfer of state and territory employees involved in state, territory and regional purchasing functions (and other state and territory employees if the hospitals and other providers themselves are transferred across).

- Following transfer, the full responsibilities of the regional purchasing organisations would need to be more carefully designed and progressively introduced, national requirements for casemix purchasing and funding for training and research clarified, and national, state, territory and regional administrative structures further rationalised.

- A dedicated project team under the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) with associated bilateral task forces, to track all government expenditure to each region, commence joint planning for the initial handover and commence ‘due diligence’ work.

There is clearly room to modify these details of the transition, just as there is to modify the details of the model. The idea of a joint health commission to help with the transition has some merit, so long as it has a clear charter from federal, state and territory ministers and a firm time limit so that it is not given ongoing responsibilities which should be passed back to officials in ministerial departments.

Private health insurance

Having a single government funder and/or single government purchaser would make further reform of private health insurance arrangements easier. Current arrangements are extraordinarily complex, in no small part because of the impact of multiple government funders. These contribute to distortions in hospital markets, with privately insured patients often not being told of the consequences of being admitted as a public or private patient, and with the competition amongst hospitals for public and private patients being far from even-handed.

But before addressing this issue, there is a fundamental philosophical question that should be firmly settled by explicit government (and opposition) policy. The debate surrounding this question reflects sharp differences on the philosophical question of the appropriate role of private health insurance in a universal healthcare system. The question relates to the concept of equity and choice and the balance between these two objectives.

At one end of the spectrum is the Canadian approach to equity which rules out private funding, either through insurance or directly, for services covered by the universal system. There is no right to jump the queue even if users pay to do so themselves, nor to seek choice beyond that allowed for in the universal system. This has been one of the ‘principles’ of the Canadian Medicare system though it has recently been subject to legal challenge.

The approach in the UK is a little more flexible, allowing people to obtain health services outside the NHS, but at full cost to those electing to do so, with no allowance for the cost the NHS might otherwise have faced.

The traditional Australian approach predates the current private health insurance rebate by many decades. It effectively allows some of the costs otherwise met by the universal system to be available to those who choose private health insurance. Mostly, and on average, this support is below that otherwise available, and those with private health insurance do draw considerably on their own money for premiums and out-of-pocket expenses (Podger 2006a).

The US approach is at the other extreme, with no universal system and with considerable variation in the services available and the levels of out-of-pocket expenses according to the details of the chosen insurance policy.

Most Australians would quickly reject the US approach as not meeting the basic equity objective of national health systems, but the debate between the other approaches is not so much a matter of analysis but of personal views on the precise balance between equity and choice. The traditional Australian approach is to be preferred, with two critical conditions:

Broadly speaking, the Australian system meets the first condition, but there are serious questions about the second. The average hospital subsidy for insured people is around 72% of that for uninsured, but there are wide variations, and this figure does not take into account tax arrangements. Increasingly, the latter are acting as a means test on the public system.

With large numbers of privately insured patients, some of whom are only insured because the tax system forces them to be so, there is a lot of room for game-playing by the members, their funds, the hospitals and the doctors. Members may choose low-cost premiums with high front-end deductibles and then always present as a public patient. Insurers may be very happy for members to present as public patients. Public hospitals may prefer patients to go private in order to gain additional revenue (and, where casemix is not used rigorously, not to lose any public funds despite losing a public patient); private hospitals may overstate their capability to care for emergency and complex cases to attract patients. Doctors may encourage patients to go private to obtain higher fees from funds and co-payments from patients.

A better model, only possible with a single government funder, is to require the private funds to meet the hospital costs of their members whether they present as public or private patients, and for the government to provide transparent subsidies to the funds that reflect this arrangement. Then there would be an even playing field for hospital care for both public and private patients, and the distinction between the nature of care, the timing and any co-payments for different private health insurance product lines, would be fully apparent to members and potential members.

This would still leave the problem of doctors resisting firm agreements with funds on billing practices, but would at last remove most of the confusing choices offered to patients on admission to hospital.

Short of such a systemic change, insistence on casemix funding of public patients would at least remove one distortion in the system, taking away most of the incentive for public hospitals to pressure patients to go private (as they would lose the government funding for the public patient when gaining the private funding for the private patient).

The changes suggested here are fully consistent with the changes required under the Scotton model of managed competition, but fall far short of that radical proposal. Scotton’s model would provide privately insured people the full government subsidy available via Medicare, and would extend private insurance arrangements to the full range of health and related services. But this is a distant prospect at this stage, although there is room for considerable reform of private health insurance, allowing more competition into the health system, if first there is a move to a single government funder.

CONCLUSION

Despite the generally good performance of the Australian health system, it is facing new problems that are exposing more clearly its underlying weaknesses: its program boundaries exacerbated by multiple funders that get in the way of patient-oriented care and allocational efficiency.

While recent and prospective incremental reforms may paper over some of the worst cracks, and genuinely improve services for many people, the fundamental problem of multiple funders will continue to give rise to inappropriate care and poor use of resources.

There is much common ground amongst reform advocates: the need for a single government funder and/or purchaser, the use of regional planning frameworks, greater emphasis on primary care and prevention, better use of information, and more sophisticated use of purchasing. While differences remain over the precise details of reform options, this degree of common ground suggests systemic reform is achievable.

Note: Some of the material in this chapter is drawn from:

- Podger A 2006a Directions for Health Reform in Australia. In: Productivity Commission, Productive Federalism: Proceedings of a Roundtable, Canberra

- Podger A 2006b A Model Health System for Australia, Inaugural Menzies Lecture, Menzies Centre for Public Health Policy, Canberra. Sections of this material were also published as three articles in the Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management – 2006 A Model Health System for Australia Part 1: Directions for reform of the Australian health system 1(1):10–16; 2006 Part 2: What should a (single) Commonwealth funded public health system look like? 1(2):8–14; 2007 Part 3: How could this system change be introduced and what is the role of private health insurance? 2(1)8–16.