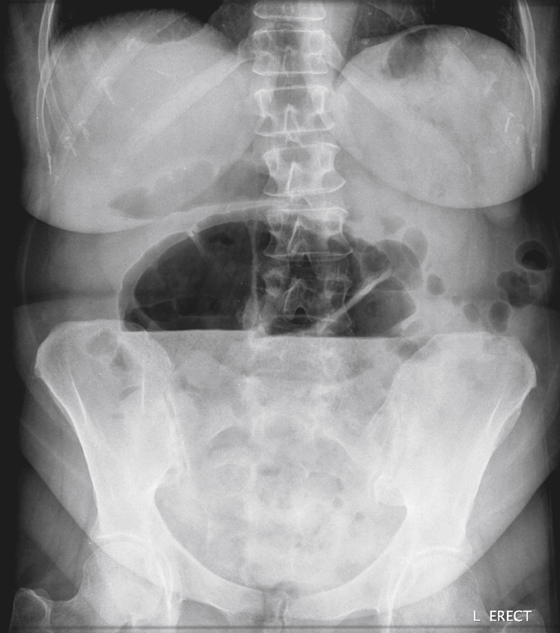

History: A 68-year-old woman presents with sudden onset of severe colicky abdominal pain and vomiting.

1. Which choice is the most likely diagnosis for this patient?

D. Colonic ileus (Ogilvie’s syndrome)

2. Which of the following regarding cecal volvulus is true?

A. There is a mobile cecum due to a mobilization of the bowel at previous surgery.

B. The cecum is a rare site of volvulus, accounting for 5% of colonic volvulus cases.

3. CT is a problem-solving tool suitable to aid in the diagnosis of cecal volvulus. Which of these choices is a sign of a cecal volvulus?

C. “Swirl” sign at the root of the mesentery

D. Displacement of the cecum adjacent to the liver

4. Which of the following regarding treatment of cecal volvulus is true?

A. Colonoscopic reduction has the same long-term results as for sigmoid volvulus.

B. Surgical reduction is a very risky option and is a management choice of last resort.

C. The surgical treatment of choice is cecal resection with loop ileostomy.

D. CT influences treatment by detecting complications of volvulus.

ANSWERS

CASE 3

Cecal Bascule

1. B

2. C

3. B

4. D

References

Bobroff LM, Messinger NH, Subbarao K, et al: The cecal bascule. Am J Roentgenol. 1972;115:249–252.

Cross-Reference

Gastrointestinal Imaging: THE REQUISITES, 3rd ed, p 310.

Comment

A volvulus is the twisting or torsion of a segment of bowel. The degree of severity and possibility of complications depend on the tightness of the twist and lack of spontaneous untwisting of the bowel. The number of volvuli that occur and spontaneously resolve is probably much higher than most radiologists appreciate.

The most common volvulus occurs in the sigmoid colon (50%-75% of cases). The cecum is the next most common site, seen in 20% to 40% of cases. Much less common are volvuli of the transverse colon and, rarely, the splenic flexure.

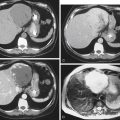

There are two types of cecal volvulus: the common torsion type and the much less common cecal bascule (about 10% of all cecal volvuli are bascules, as shown in this case). The more common cecal volvulus twists around its lumen axis. The torsion acts as an obstruction of the ascending colon. If the ileocecal valve is competent (allows only unidirectional flow) the luminal axis of the air-distended cecum is directed across the abdomen toward the spleen. Obviously, at a certain point, a greatly dilated thin-walled cecum will burst, resulting in perforation, spillage of colon contents, and peritonitis. If the ileocecal valve is not competent, the findings can be less clear.

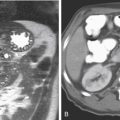

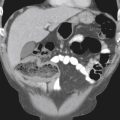

In the case of a bascule, the cecum does not twist about its luminal axis but instead flips up and over an adhesion across the ascending colon, and the dilated cecum is seen clearly as a right-sided or midline subhepatic air-filled structure (see figures). The cause of the adhesion or band over which the cecum flips is unknown. It may be congenital.