Procedure 29 Release of a Spastic Elbow Flexion Contracture

![]() See Video 22: Biceps and Brachialis Lengthening

See Video 22: Biceps and Brachialis Lengthening

Examination/Imaging

Clinical Examination

The three major causes of an elbow flexion contracture resulting from spasticity are cerebral palsy, stroke, and traumatic brain injury. There are some differences in the approach to treatment among these three causes.

The three major causes of an elbow flexion contracture resulting from spasticity are cerebral palsy, stroke, and traumatic brain injury. There are some differences in the approach to treatment among these three causes.

Extent of release: The spastic muscles that contribute to an elbow flexion contracture are the biceps brachii, the brachialis, and the brachioradialis. Depending on the degree of contracture and amount of volitional control, they can be either lengthened or divided sequentially. The lacertus fibrosis is always divided, and an anterior capsulectomy of elbow joint or a Z-lengthening of the antecubital skin may be rarely required.

Extent of release: The spastic muscles that contribute to an elbow flexion contracture are the biceps brachii, the brachialis, and the brachioradialis. Depending on the degree of contracture and amount of volitional control, they can be either lengthened or divided sequentially. The lacertus fibrosis is always divided, and an anterior capsulectomy of elbow joint or a Z-lengthening of the antecubital skin may be rarely required.

Imaging

X-ray of the elbow joint: Radiography can help differentiate muscle contracture from joint contracture. It is especially useful in traumatic brain injury, in which heterotopic ossification around the elbow is common and can be associated with compression of the ulnar nerve.

X-ray of the elbow joint: Radiography can help differentiate muscle contracture from joint contracture. It is especially useful in traumatic brain injury, in which heterotopic ossification around the elbow is common and can be associated with compression of the ulnar nerve.

Nerve block: A local anesthetic nerve block can be used to differentiate between muscle spasticity and muscle contracture.

Nerve block: A local anesthetic nerve block can be used to differentiate between muscle spasticity and muscle contracture.

Dynamic electromyography: This helps in identifying spastic and flaccid muscles and can help with the surgical decision-making process. It can show the muscles under volitional control and determine phasic activity.

Dynamic electromyography: This helps in identifying spastic and flaccid muscles and can help with the surgical decision-making process. It can show the muscles under volitional control and determine phasic activity.

Surgical Anatomy

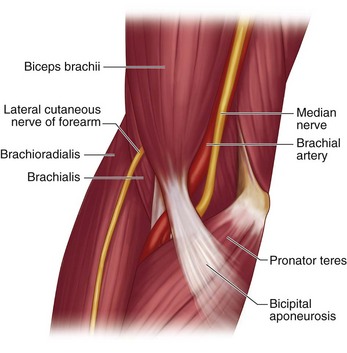

The cubital fossa, bounded medially by the pronator teres and laterally by the brachioradialis, contains the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm, the tendon of the biceps brachii, the brachial artery, and median nerve. The brachial artery and median nerve are located medial to the biceps brachii, and the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm is lateral to the biceps brachii. The lacertus fibrosus, also known as the bicipital aponeurosis, continues distally as deep fascia of the forearm (Fig. 29-1).

The cubital fossa, bounded medially by the pronator teres and laterally by the brachioradialis, contains the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm, the tendon of the biceps brachii, the brachial artery, and median nerve. The brachial artery and median nerve are located medial to the biceps brachii, and the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm is lateral to the biceps brachii. The lacertus fibrosus, also known as the bicipital aponeurosis, continues distally as deep fascia of the forearm (Fig. 29-1).

Positioning

Exposures

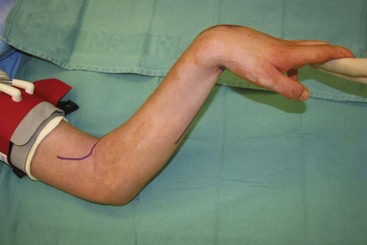

A 15-cm long “lazy S”–shaped incision is made over the antecubital fossa. The incision begins on the lateral aspect of the arm over the origin of the brachioradialis muscle and gently curves over the antecubital crease distally toward the anteromedial aspect of the forearm (see Fig. 29-2).

A 15-cm long “lazy S”–shaped incision is made over the antecubital fossa. The incision begins on the lateral aspect of the arm over the origin of the brachioradialis muscle and gently curves over the antecubital crease distally toward the anteromedial aspect of the forearm (see Fig. 29-2).

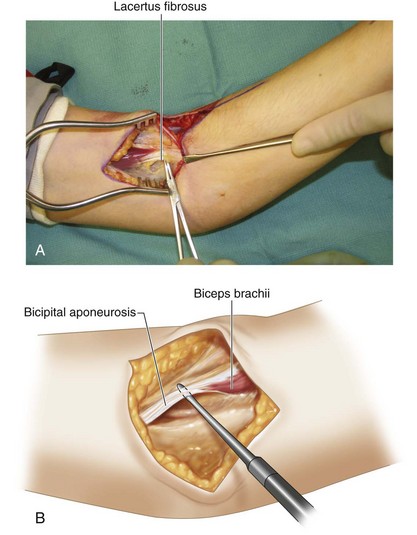

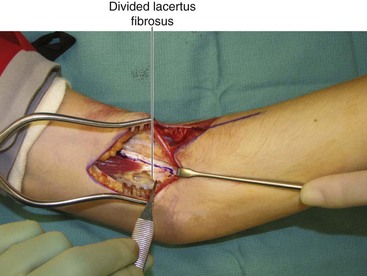

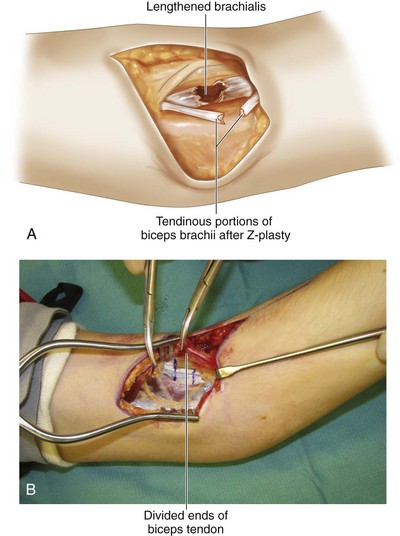

The subcutaneous dissection is continued from medial to lateral, to expose the cubital fossa. The lacertus fibrosus and the biceps brachii tendon are identified (Fig. 29-3A and B). The median nerve and brachial artery are identified medial to the biceps tendon, and the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve is identified lateral to the biceps tendon emerging from the interval between the biceps and brachialis.

The subcutaneous dissection is continued from medial to lateral, to expose the cubital fossa. The lacertus fibrosus and the biceps brachii tendon are identified (Fig. 29-3A and B). The median nerve and brachial artery are identified medial to the biceps tendon, and the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve is identified lateral to the biceps tendon emerging from the interval between the biceps and brachialis.

Procedure

Step 1

Step 2

The contracted biceps brachii is exposed and dissected distal to its insertion. The decision regarding the degree of biceps lengthening should be made at this time. A fractional lengthening is performed for mild contractures, and a Z-lengthening is performed for more severe contractures.

The contracted biceps brachii is exposed and dissected distal to its insertion. The decision regarding the degree of biceps lengthening should be made at this time. A fractional lengthening is performed for mild contractures, and a Z-lengthening is performed for more severe contractures.

A fractional lengthening is performed by making two transverse and slightly oblique cuts, 1 to 2 cm apart, halfway through the tendinous portion of the musculotendinous junction, with care taken to leave the muscle fibers intact. One cut is made on the lateral side of the tendon, and the other cut is made on the medial side. Passive extension of the elbow allows separation of these tenotomy sites, keeping the muscle in continuity.

A fractional lengthening is performed by making two transverse and slightly oblique cuts, 1 to 2 cm apart, halfway through the tendinous portion of the musculotendinous junction, with care taken to leave the muscle fibers intact. One cut is made on the lateral side of the tendon, and the other cut is made on the medial side. Passive extension of the elbow allows separation of these tenotomy sites, keeping the muscle in continuity.

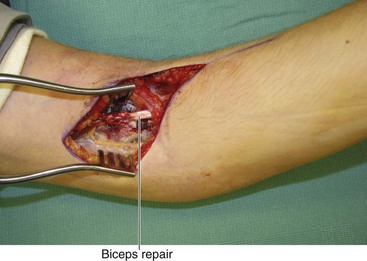

A Z-lengthening (step-cut) is performed over as much length of the tendon as possible because this gives more tendon substance to do a strong repair (see Fig. 29-4).

A Z-lengthening (step-cut) is performed over as much length of the tendon as possible because this gives more tendon substance to do a strong repair (see Fig. 29-4).

Step 3

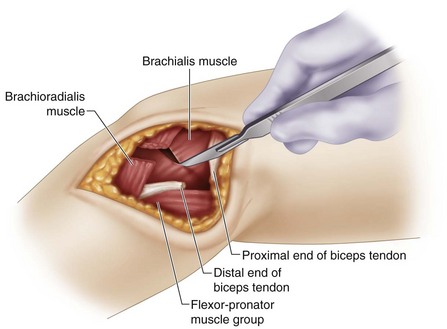

The release of the biceps brings the brachialis into view. Depending on the degree of contracture and the volitional control of the patient, a partial or complete release of the brachialis can be done.

The release of the biceps brings the brachialis into view. Depending on the degree of contracture and the volitional control of the patient, a partial or complete release of the brachialis can be done.

A partial release can be done using one or two incisions (Fig. 29-5A). A double incision gives more release. A transverse incision is made over the aponeurotic portion on the anterior aspect of the muscle, leaving the muscle intact. If two incisions are used, they are spaced about 1 to 2 cm apart (Fig. 29-5B).

A partial release can be done using one or two incisions (Fig. 29-5A). A double incision gives more release. A transverse incision is made over the aponeurotic portion on the anterior aspect of the muscle, leaving the muscle intact. If two incisions are used, they are spaced about 1 to 2 cm apart (Fig. 29-5B).

In patients who have severe contractures without volitional control, the brachialis can be completely transected using electrocautery.

In patients who have severe contractures without volitional control, the brachialis can be completely transected using electrocautery.

Step 4

At this point, assessment of the brachioradialis is done. A partial or complete release of the brachioradialis can be performed, depending on the degree of spasticity and the volitional control of the patient. Dissection is carried out between the brachialis and the brachioradialis.

At this point, assessment of the brachioradialis is done. A partial or complete release of the brachioradialis can be performed, depending on the degree of spasticity and the volitional control of the patient. Dissection is carried out between the brachialis and the brachioradialis.

Step 4 Pearls

If the brachioradialis has volitional control and the elbow contracture is not very severe, a partial release can be done through a separate 3-cm longitudinal incision made on the dorsoradial aspect of the mid-forearm. The tendinous portion of the brachioradialis is on its deeper surface; the muscle needs to be reflected to visualize this portion. A transverse incision is used to divide only the tendon, keeping the muscle in continuity.

Postoperative Care and Expected Outcomes

A long-arm plaster of Paris splint that keeps the elbow at 30 degrees of flexion is applied.

A long-arm plaster of Paris splint that keeps the elbow at 30 degrees of flexion is applied.

Ten days after surgery, the wound is inspected, and sutures are removed. If a Z-lengthening of the biceps was done, the elbow is splinted for an additional 4 weeks in 30 degrees of flexion. Active and passive range of motion is initiated thereafter. Night splints are used for an additional 3 weeks to protect the biceps tendon repair. If only a fractional lengthening of the biceps was done and there was no repair of the biceps tendon, the patient can be started on mobilization immediately.

Ten days after surgery, the wound is inspected, and sutures are removed. If a Z-lengthening of the biceps was done, the elbow is splinted for an additional 4 weeks in 30 degrees of flexion. Active and passive range of motion is initiated thereafter. Night splints are used for an additional 3 weeks to protect the biceps tendon repair. If only a fractional lengthening of the biceps was done and there was no repair of the biceps tendon, the patient can be started on mobilization immediately.

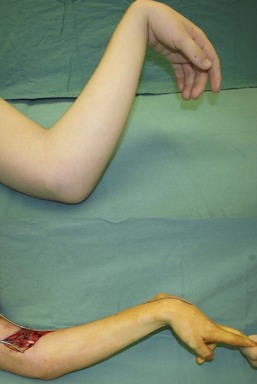

Patients who undergo fractional lengthening of the biceps can expect a 10- to 30-degree improvement in the flexion contracture without appreciable loss of flexion power. Patients who undergo Z-lengthening can expect up to a 45- to 60-degree improvement in flexion contracture, but they do lose elbow flexion power. It is important to avoid full extension of the elbow in patients with volitional control because difficulty with elbow flexion after a full release may become a greater problem for the patient (Fig. 29-9).

Patients who undergo fractional lengthening of the biceps can expect a 10- to 30-degree improvement in the flexion contracture without appreciable loss of flexion power. Patients who undergo Z-lengthening can expect up to a 45- to 60-degree improvement in flexion contracture, but they do lose elbow flexion power. It is important to avoid full extension of the elbow in patients with volitional control because difficulty with elbow flexion after a full release may become a greater problem for the patient (Fig. 29-9).