CASE 29 Acute Vessel Closure During Coronary Intervention

Cardiac catheterization

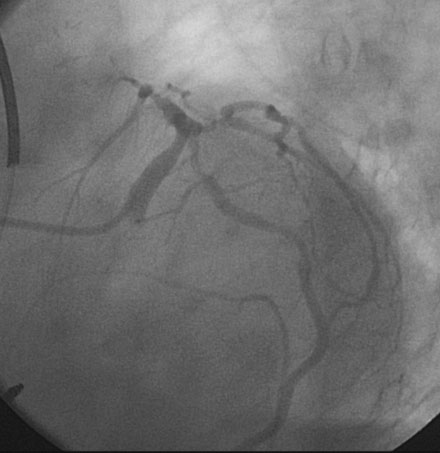

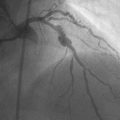

Representative angiograms of her left coronary artery are shown in Figures 29-1, 29-2 and Videos 29-1, 29-2. A complex lesion was present in the proximal portion of the ramus intermedius at a bifurcation. The proximal to midsegment of the circumflex was also severely diseased. Importantly, this artery branched from the left main with marked angulation, clearly seen in the left anterior oblique view with caudal angulation (see Figure 29-1).

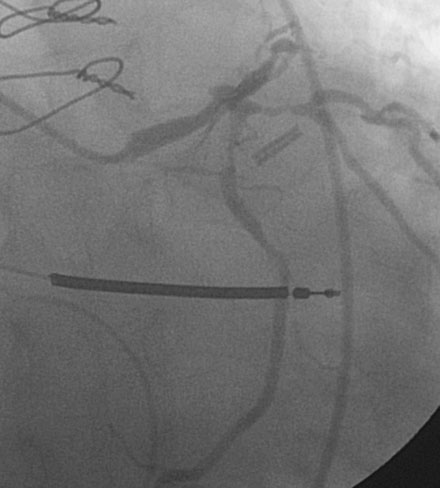

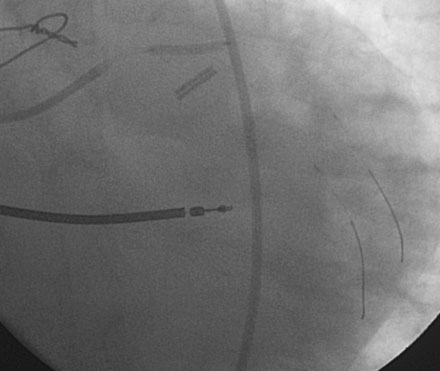

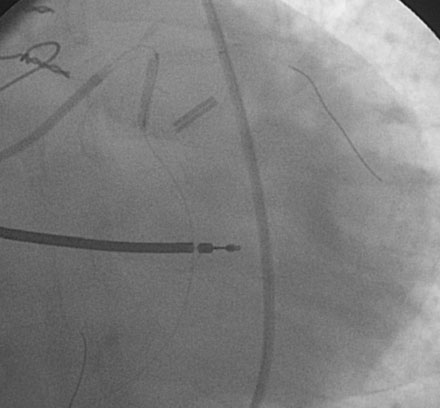

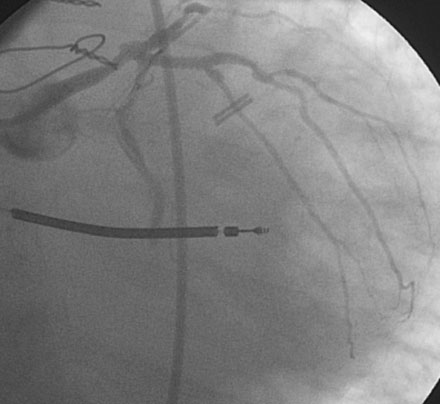

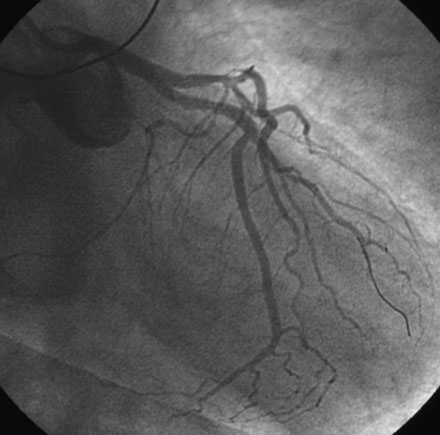

Procedural anticoagulation was accomplished with an intravenous heparin bolus to achieve an activated clotting time greater than 300 seconds and a supportive guide catheter was chosen (6 French JCL 4.5). The operator began with the ramus intermedius (Figure 29-3). This lesion was successfully treated with balloon angioplasty (2.5 mm diameter by 15 mm long compliant balloon) followed by placement of an everolimus-eluting stent (2.75 mm diameter by 18 mm long) (Figure 29-4 and Video 29-3).

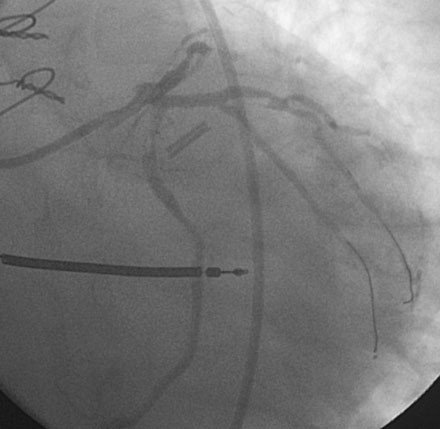

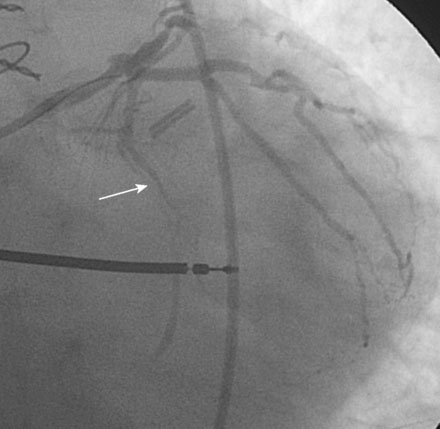

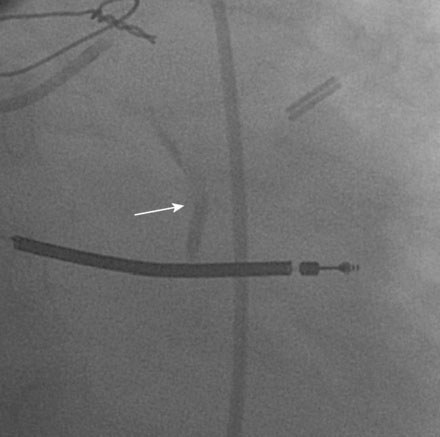

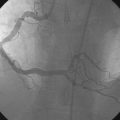

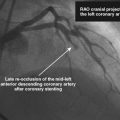

Following the successful procedure on the ramus intermedius, the operator turned attention to the circumflex. Due to excessive angulation, the operator was unable to pass a 0.014 inch floppy-tipped conventional guidewire; a hydrophilic guidewire ultimately proved successful. The operator used a compliant balloon (2.5 mm diameter by 15 mm long) to predilate the lesion (Figures 29-5, 29-6 and Video 29-4) then removed the balloon catheter and attempted to pass an everolimus-eluting stent (3.0 mm diameter by 15 mm long). This was not successful because the stent would not advance around the acute angle. The guidewire was replaced with a stiffer shaft wire (Boston Scientific Mailman) and a shorter bare-metal stent was also attempted (3.0 mm diameter by 9 mm long) but failed to advance as well. During attempts to advance the stent, the guide catheter disengaged and distal wire access was lost. The guide was reengaged. Again, the operator had great difficulty advancing a 0.014 inch polymer-tipped guidewire and created a dissection resulting in vessel closure (Figures 29-7, 29-9 and Videos 29-5, 29-6). Attempts to regain the distal lumen using a variety of other guidewires failed. The patient reported chest pain but remained hemodynamically stable without arrhythmia. At this point, the procedure was stopped and the patient admitted to the coronary care unit.

Discussion

Abrupt vessel closure after angioplasty is a serious complication associated with death, myocardial infarction, or need for emergency bypass surgery.1 Most cases of abrupt vessel closure are due to extensive dissection of the artery with vessel occlusion caused by intimal flaps, intramural hematoma, or thrombus. During the balloon era, abrupt vessel closure complicated 2% to 8% of

coronary interventions and the only definitive therapy consisted of emergency bypass surgery. Coronary stents offered the first effective percutaneous solution and dramatically reduced the need for emergency surgery.

Despite the advances in technology, abrupt closure remains an important risk in the current era. As demonstrated by this case, the inability to deliver a stent to a complex lesion or an extensively dissected segment leaves the operator few options in the event of vessel closure. Proximal vessel tortuosity, extreme angulation, heavy coronary calcification, and noncompliant vessels are all scenarios where a stent might not be deliverable. At this juncture, the operator is faced with the decision of emergency bypass surgery versus conservative medical management of the closed vessel and associated myocardial infarction. Emergency bypass surgery, still necessary in about 0.4% of percutaneous coronary interventions, is a fairly morbid event, associated with an in-hospital mortality of 8%, and is more likely to be justified when the occluded vessel supplies a large amount of myocardium.2 In the case presented here, the benefit of revascularizing a small vascular territory was greatly outweighed by the risk of emergent surgery in a patient with significant comorbid conditions.

1. Klein L.W. Coronary complications of percutaneous coronary intervention: A practical approach to the management of abrupt closure. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;64:395-401.

2. Roy P., de labriolle A., Hanna N., Bonello L., Okabe T., Slottow T.L.P., Steinberg D.H., Torguson R., Kaneshige K., Xue Z., Satler L.F., Kent K.M., Suddath W.O., Pichard A.D., Lindsay J., Waksman R. Requirement for emergent coronary artery bypass surgery following percutaneous coronary intervention in the stent era. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:950-953.