Procedure 28 Pronator Teres Rerouting

Examination/Imaging

Clinical Examination

The pronation deformity can be classified into mild (forearm is in partially prone position with preserved active and/or passive motion), moderate (forearm is fully pronated with preserved active and/or passive motion), or severe (forearm is fully pronated with no active and/or passive motion—fixed pronation contracture). A mild deformity does not need surgery because the posture puts the hand in a functional position. No surgery is required for patients with moderate pronation deformity that can actively supinate the hand to neutral. If the patient can actively supinate the arm but cannot bring it to neutral, a release of the pronator quadratus (PQ) and a flexor-pronator slide can be considered. Pronator teres (PT) rerouting is useful in patients who have no active supination but full passive supination. Patients with a fixed pronation contracture may need release of the PQ, a flexor-pronator slide, release of the interosseous membrane, and occasionally a corrective osteotomy to place the forearm in neutral position.

The pronation deformity can be classified into mild (forearm is in partially prone position with preserved active and/or passive motion), moderate (forearm is fully pronated with preserved active and/or passive motion), or severe (forearm is fully pronated with no active and/or passive motion—fixed pronation contracture). A mild deformity does not need surgery because the posture puts the hand in a functional position. No surgery is required for patients with moderate pronation deformity that can actively supinate the hand to neutral. If the patient can actively supinate the arm but cannot bring it to neutral, a release of the pronator quadratus (PQ) and a flexor-pronator slide can be considered. Pronator teres (PT) rerouting is useful in patients who have no active supination but full passive supination. Patients with a fixed pronation contracture may need release of the PQ, a flexor-pronator slide, release of the interosseous membrane, and occasionally a corrective osteotomy to place the forearm in neutral position.

Before considering PT rerouting, one must ensure that the patient has the following:

Before considering PT rerouting, one must ensure that the patient has the following:

Surgical Anatomy

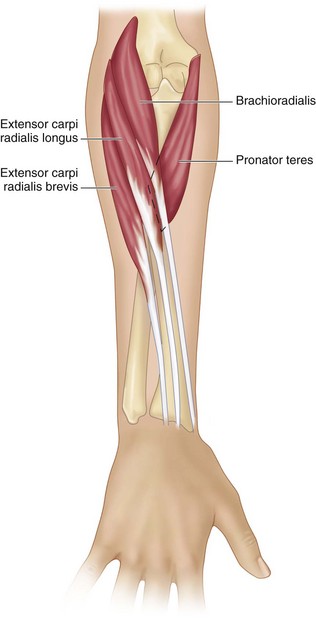

The PT originates at the medial epicondyle and inserts over the volar surface of the radius via a wide fascial attachment.

The PT originates at the medial epicondyle and inserts over the volar surface of the radius via a wide fascial attachment.

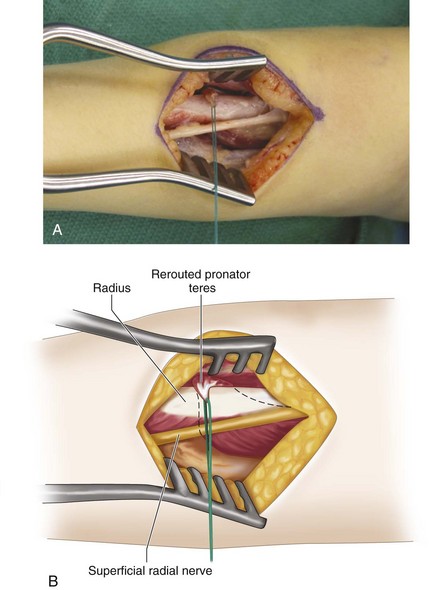

The insertion of the PT is found at the mid-forearm under the brachioradialis (Fig. 28-1).

The insertion of the PT is found at the mid-forearm under the brachioradialis (Fig. 28-1).

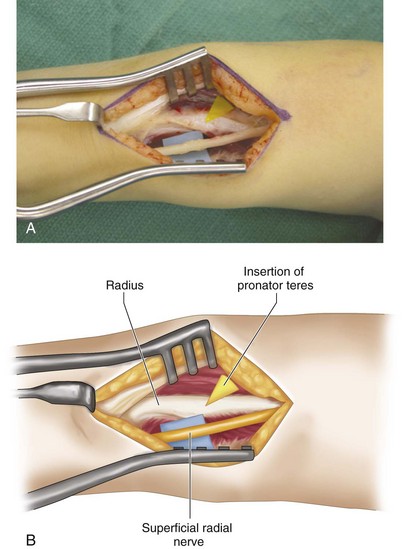

The superficial radial nerve, which is under the brachioradialis, should be isolated and protected.

The superficial radial nerve, which is under the brachioradialis, should be isolated and protected.

Exposures

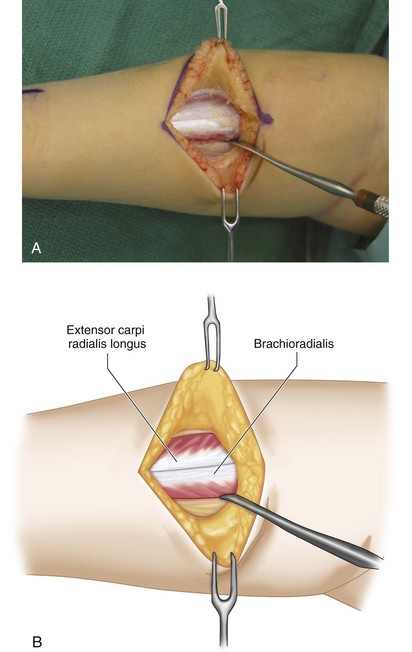

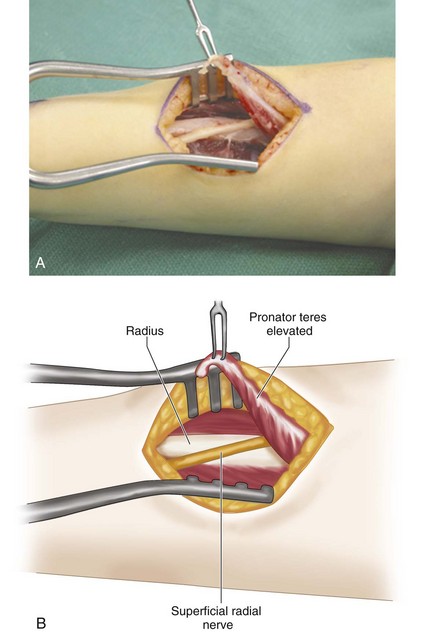

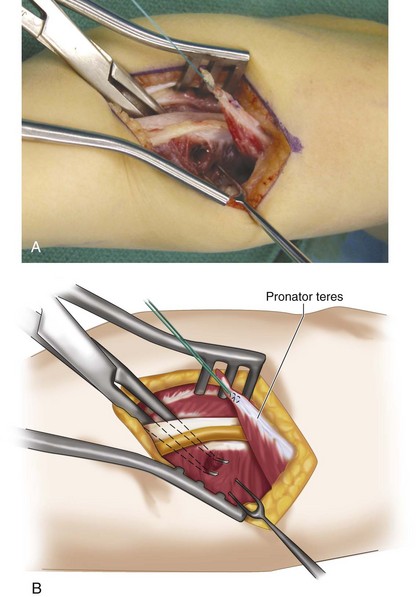

A 6-cm longitudinal incision is made over the volar radial aspect of the mid-forearm (Fig. 28-2). This incision is centered over the palpable musculotendinous junction of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) and extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL). The forearm fascia is divided, and the tendons of the ECRB and ECRL are identified (Fig. 28-3A and B). The brachioradialis is identified radial to the ECRL, and it is retracted ulnarly along with the ECRL. The superficial branch of the radial nerve should be identified under the brachioradialis and protected. This will bring into view the insertion of the PT (Fig. 28-4A and B).

A 6-cm longitudinal incision is made over the volar radial aspect of the mid-forearm (Fig. 28-2). This incision is centered over the palpable musculotendinous junction of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) and extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL). The forearm fascia is divided, and the tendons of the ECRB and ECRL are identified (Fig. 28-3A and B). The brachioradialis is identified radial to the ECRL, and it is retracted ulnarly along with the ECRL. The superficial branch of the radial nerve should be identified under the brachioradialis and protected. This will bring into view the insertion of the PT (Fig. 28-4A and B).

Procedure

Step 2

Step 3

Step 6

Step 7

The PT is now attached to the radius. The attachment of the PT to the bone can be achieved in several ways. A Mitek Mini bone anchor can be inserted over the dorsal radius to provide attachment of the sutures.

The PT is now attached to the radius. The attachment of the PT to the bone can be achieved in several ways. A Mitek Mini bone anchor can be inserted over the dorsal radius to provide attachment of the sutures.

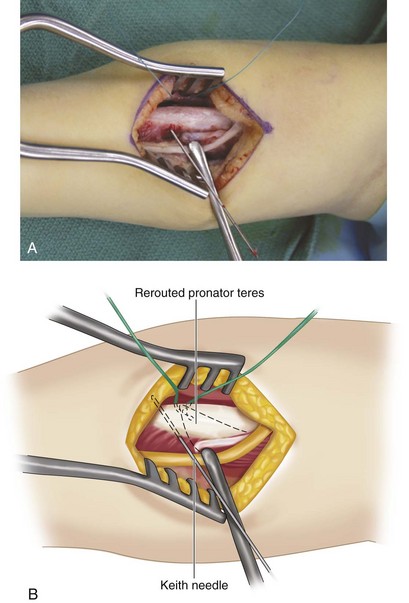

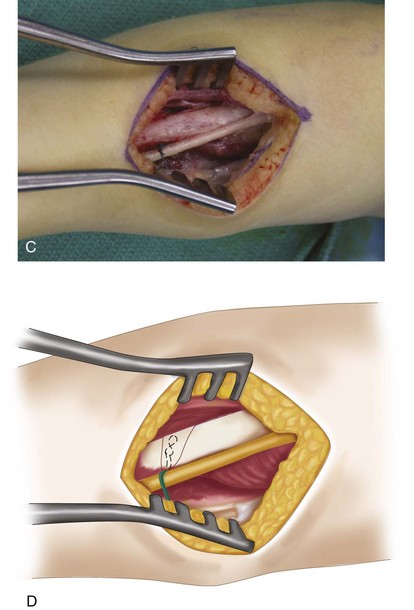

Our preference is to use a Keith needle to drill two holes through the radius, and then to pass the sutures through the radius and tie them over the opposite cortex. This form of attachment is quite strong (Fig. 28-8A to D).

Our preference is to use a Keith needle to drill two holes through the radius, and then to pass the sutures through the radius and tie them over the opposite cortex. This form of attachment is quite strong (Fig. 28-8A to D).

Postoperative Care and Expected Outcomes

The forearm is splinted in the fully supinated position above the elbow for the next 6 weeks to allow reattachment of the fascia and tendon to the radius (Fig. 28-9). After 6 weeks of splinting, the patient is allowed unrestricted motion. Therapy typically is not necessary because the patient should automatically be able to learn how to use the tendon transfer for supination. Another advantage of the rerouting procedure is to take tension off the PT (a weak elbow flexor) to enable the patient to extend the elbow.

The forearm is splinted in the fully supinated position above the elbow for the next 6 weeks to allow reattachment of the fascia and tendon to the radius (Fig. 28-9). After 6 weeks of splinting, the patient is allowed unrestricted motion. Therapy typically is not necessary because the patient should automatically be able to learn how to use the tendon transfer for supination. Another advantage of the rerouting procedure is to take tension off the PT (a weak elbow flexor) to enable the patient to extend the elbow.

The patient can expect an improvement in active supination ranging from 45 to 90 degrees. However, there will be some loss of pronation. The results are less satisfactory in patients who do not have active pronation before the procedure.

The patient can expect an improvement in active supination ranging from 45 to 90 degrees. However, there will be some loss of pronation. The results are less satisfactory in patients who do not have active pronation before the procedure.

Gschwind C, Tonkin M. Surgery for cerebral palsy. Part 1: classification and operative procedures for pronation deformity. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1992;17:391-395.

Sakellarides HT, Mital MA, Lenzi WD. Treatment of pronation contractures of the forearm in cerebral palsy by changing the insertion of the pronator radii teres. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1981;63:645-652.

Strecker WB, Emanuel JP, Daily L, Manske PR. Comparison of pronator tenotomy and pronator re-routing in children with spastic cerebral palsy. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1988;13:540-543.