CHAPTER 28

de Quervain Tenosynovitis

Definition

Tenosynovitis is inflammation of a tendon and its enveloping synovial sheath [7]. de Quervain tenosynovitis is classically defined as a stenosing tenosynovitis of the synovial sheath of tendons of the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis muscles in the first compartment of the wrist due to repetitive use [2]. Fritz de Quervain first described this condition in 1895 [3]. Histologic studies have found that this disorder is characterized by degeneration and thickening of the tendon sheath and that it is not an active inflammatory condition [8].

In fact, de Quervain described thickening of the tendon sheath compartment at the distal radial end of the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor longus [3]. Extensor triggering, which is manifested by locking in extension, is rare but has also been reported in de Quervain tenosynovitis with a prevalence of 1.3% [1].

Overexertion related to household chores and recreational activities including piano playing, sewing, knitting, typing, bowling, golfing, and fly-fishing have been reported to cause de Quervain tenosynovitis. Workers involved with fast repetitive manipulations such as pinching, grasping, pulling, and pushing are also at risk [6]. Excessive use of the text messaging feature on a cellular phone has now also been linked to this painful condition [9].

For a majority of cases, the onset of de Quervain tenosynovitis is gradual and not associated with a history of acute trauma, although several authors have noted a traumatic etiology, such as falling on the tip of the thumb [6].

de Quervain tenosynovitis primarily affects women (gender ratio approximately 10:1) between the ages of 35 and 55 years. There is no predilection for right versus left side, and no racial differences have been observed [6].

Symptoms

Patients may complain of pain in the lateral wrist during grasp and thumb extension [3]. They may also describe pain with palpation over the lateral wrist [10]. Symptoms are often gradual in onset and persistent for several weeks or months, and there is often a history of chronic overuse of the wrist and the hand [11]. Pain is the most prominent symptom quality, but some patients report stiffness as well. Pain is often described as severe and may be sufficiently intense to render the hand useless [6]. Paresthesia in the distribution of the anterior terminal branch superficial radial nerve is uncommon [6].

Physical Examination

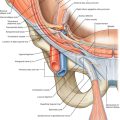

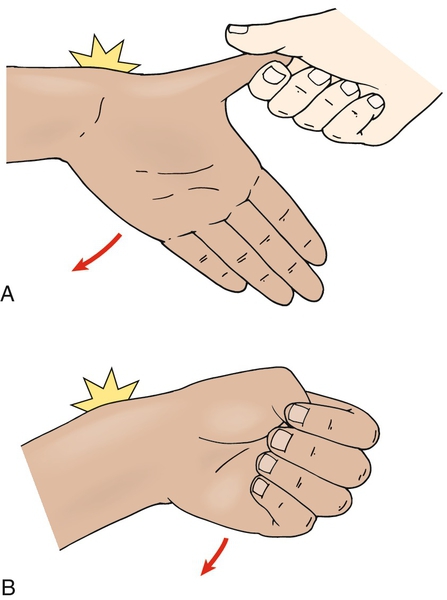

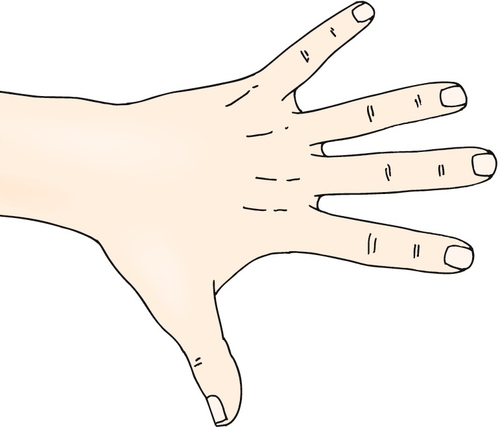

On examination, the findings of local tenderness and moderate swelling around the radial styloid are likely to be present [11]. A positive Finkelstein test result can confirm the diagnosis [12]. The Finkelstein test is performed by grasping the patient’s thumb and quickly abducting the hand in ulnar deviation [4] (Fig. 28.1). Reproduction of pain is a positive test result. A similar test, described by Eichhoff in 1927, provides ulnar deviation while the patient is flexing the thumb and curling fingers around it. Pain should disappear the moment the thumb is again extended, even if the ulnar abduction is maintained [3]. The Eichhoff test is sometimes erroneously called the Finkelstein test. The Brunelli test maintains the wrist in radial deviation while forcibly abducting the thumb [3] (Fig. 28.2). Pain over the radial styloid from these provocative stretch maneuvers differentiates de Quervain tenosynovitis from arthritis of the first metacarpal joint [10]. Strength and sensation are expected to be normal in patients with de Quervain tenosynovitis. However, strength, particularly grip and pinch strength, may be decreased from pain or disuse secondary to pain [13]. A comprehensive examination of the neck and entire upper extremity should be performed before the wrist examination to rule out radiating pain from a more proximal problem, such as a herniated cervical disc [10]. Assessment of the first carpometacarpal joint, including range of motion, palpation for tenderness and crepitus, and radiographic investigation, should also be performed because injury to this joint can give a false-positive Finkelstein test result [14].

Functional Limitations

Functional impairment is believed to be caused by impaired gliding of the abductor pollicis longus or extensor pollicis brevis tendon through a narrowed fibro-osseous canal [6]. Functional impairment of the thumb is a result of mechanical impingement or pain. Activities of daily living, such as dressing, can be impaired. Fastening of buttons often causes significant pain. In addition, household chores can be limited secondary to pain. Limits in recreational activities, such as bowling, fly-fishing, sewing, and knitting, are also seen in de Quervain tenosynovitis. Workers with jobs requiring repetitive motions, such as pushing or pulling in a factory setting, are at risk for development of the condition. Thus pain from the condition can have a significant economic inpact [6].

Diagnostic Studies

Tenosynovitis of the wrist is a clinical diagnosis, but some authors recommend obtaining a wrist radiograph to rule out other potential causes of wrist pain [6]. Some clinicians report that relief of symptoms after injection of a local anesthetic into the first dorsal compartment is often helpful as a diagnostic tool [6]. When clinical findings are nondiagnostic, a bone scan can help confirm the diagnosis [2]. On ultrasound examination, tenosynovitis is characterized by hypoechoic fluid distending the tendon sheath with inflammatory changes within the tendon [15]. Newer studies use ultrasound to evaluate for subcompartmentalization within the first extensor compartment, which may complicate treatment.

Treatment

Initial

Initial treatment of de Quervain tenosynovitis is injections. There is no evidence that conservative treatment is effective in reducing symptoms of de Quervain tenosynovitis. Some literature has evaluated effectiveness of ice, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), heat, orthoses, strapping, rest, and massage. Available research does not show these techniques to be effective in the treatment of de Quervain tenosynovitis [6]; however, no randomized controlled study has been performed. One study compared splinting with rest and NSAID therapy. Only 14% of patients who were splinted were cured versus 0% with rest and NSAIDs [16].

Rehabilitation

The goals of therapy are to reduce pain and to improve function of the affected hand. Classically, therapy includes physical modalities such as ice, heat, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, ultrasound, and iontophoresis [8]. In addition, friction massage and active exercises have been employed [8]. A thumb spica splint has been used for immobilization as well [17]. A thumb spica splint is thought to be an effective way to manage symptoms because it inhibits gliding of the tendon through the abnormal fibro-osseous canal [6]. One small, randomized study demonstrated that patients with mild symptoms are more likely to improve with therapy and NSAIDs alone, with the majority of patients with moderate to severe symptoms not responding to therapy [17]. Although steroid injection is the treatment of choice for de Quervain tenosynovitis, because of the benign profile of physical therapy, it is reasonable to consider these less invasive approaches (such as ice, thumb spica splinting, and NSAIDs) as adjuvants when this disorder is mild and first treated [18].

Procedure

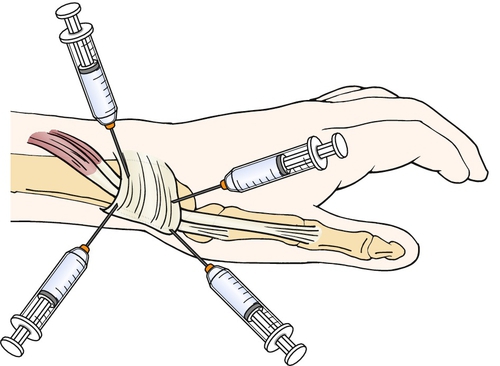

Injection of local anesthetics and corticosteroids, with or without immobilization, became popular in the 1950s [6]. It is currently the most frequent treatment modality for patients with de Quervain tenosynovitis. Injection into the first extensor compartment can relieve symptoms (Fig. 28.3). One study described an 83% cure rate with injection [16]. In recent years, multiple types of injection techniques have been compared. One study comparing a one-point injection (directed into the first compartment) versus a two-point injection technique (injection corresponding with the paths of both the extensor pollicis brevis and the abductor pollicis longus) showed the latter to be more beneficial [19]. A study evaluating treatment with a four-point injection technique (injecting both the proximal and distal locations for both extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus) showed some benefit over the two-point procedure [14]. It is essential that corticosteroid enter the compartment of both the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus for the injection to be effective. Many patients have anatomic variations with a septum creating two subcompartments. Incidence of septation of the first compartment reportedly varies in cadaveric studies from 24% to 76% [20,21]. Ultrasound-guided injections have reportedly increased improvement after injection to 97% [20]. Given the success of injections over therapy, injections remain the first-line treatment of the condition [18].

Surgery

Before 1950, surgery was considered the treatment of choice for de Quervain tenosynovitis. Now, with the success of injections, it is reserved for those whose injection therapy fails [22]. Surgery involves release of the extensor retinaculum, and both open and endoscopic techniques can be used. Partial resection of the retinaculum can be used as well [23]. The patient returns to normal activities after 2 to 3 weeks. On average, surgical success rates range from 83% to 92% [6].

Potential Disease Complications

Because of friction, the tendon sheath becomes edematous, which can further increase friction. This can eventually lead to fibrosis of the tendon [6]. The condition is characterized not by inflammation [6] but by thickening of the tendon sheath and most notably by the accumulation of mucopolysaccharide, an indicator of myxoid degeneration. These changes are pathognomonic of the condition and are not seen in control tendon sheaths. The term stenosing tenovaginitis is a misnomer; de Quervain disease is the result of intrinsic, degenerative mechanisms rather than of extrinsic, inflammatory ones [24].

Potential Treatment Complications

NSAIDs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. The most common immediate adverse reaction reported with injection was pain at the injection site (35%), followed by immediate inflammatory flare reaction (10%), temporary radial nerve paresthesia (4%), and vasovagal reaction (4%); 31% had late adverse reactions ranging from minimal skin color lightening to subcutaneous fat atrophy [6]. In this study, no postinjection infection, bleeding, or tendon rupture was seen, although this could be possible with any injection. With any type of steroid injection, there is a risk of bleeding. Repeated steroid injections have the potential to weaken the tendon and may cause a tendon rupture. Surgical treatment complications include radial nerve injury, incomplete retinacular release, and tendon subluxation [22].