CASE 28 Coronary Perforation Caused by a Guidewire

Case presentation

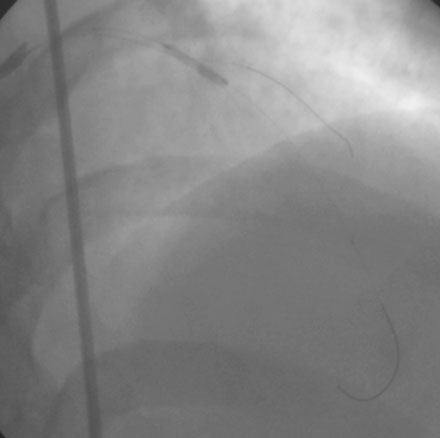

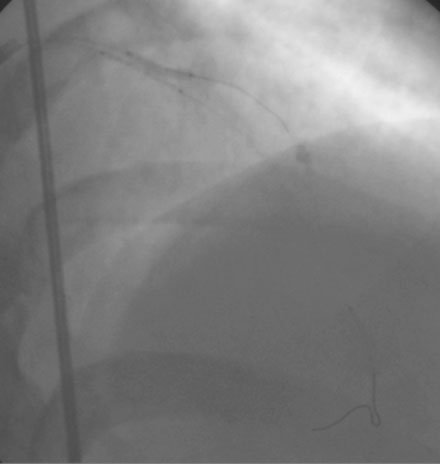

A 43-year-old man with multiple risk factors for coronary artery disease, including severe dyslipidemia, family history of premature coronary disease, and ongoing tobacco abuse, was referred for cardiac catheterization after presenting with a prolonged episode of rest ischemic chest pain and an elevated troponin I (1.3 ng/mL). Coronary angiography demonstrated three-vessel coronary disease consisting of complex and severe narrowing of the proximal to midsegment of the left anterior descending artery involving a diagonal branch (Figure 28-1 and Video 28-1), severe obstructive disease of the first obtuse marginal artery, total occlusion of the second obtuse marginal and distal left circumflex, and moderate obstructive disease of the posterior descending branch of the right coronary artery, with preserved left ventricular function. After a lengthy discussion regarding therapeutic options, the patient chose to undergo percutaneous revascularization of the lesions in the left anterior descending artery and first obtuse marginal artery.

Cardiac catheterization

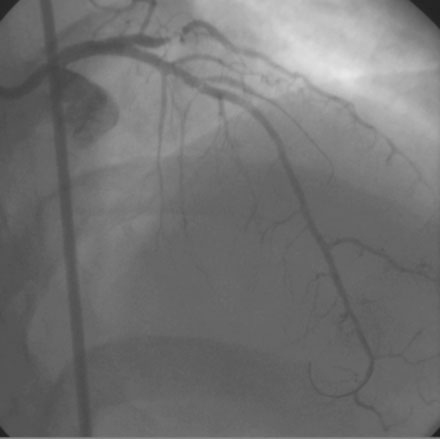

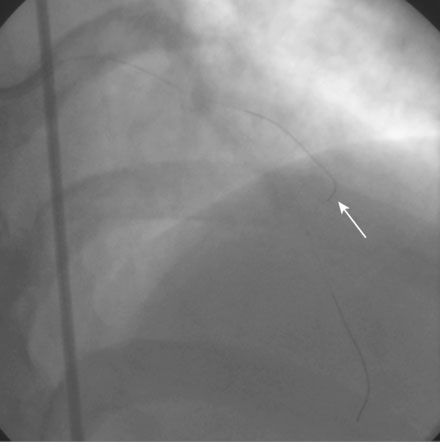

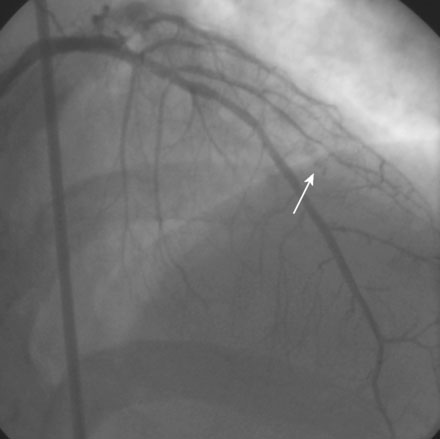

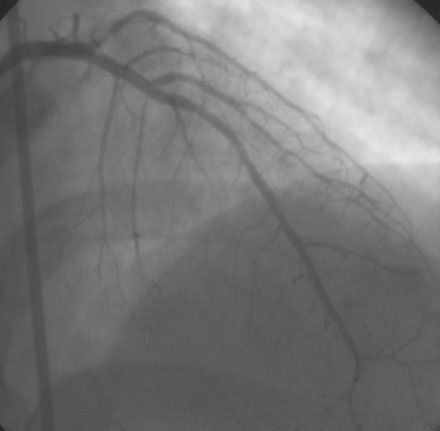

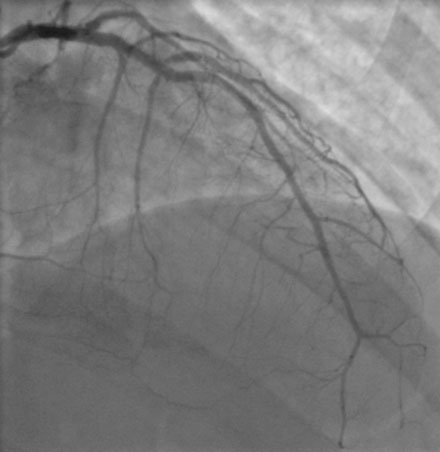

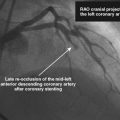

In an effort to avoid closure of the diagonal side branch, the operator chose a “crush stent” technique to treat the left anterior descending artery and diagonal branch. Using an 8 French, left Judkins 4.0 guide catheter and procedural anticoagulation consisting of unfractionated heparin (5300 units) and eptifibatide (two boluses of 15.8 mg followed by an infusion of 2 mcg/kg/min), the operator positioned a floppy-tipped 0.014 inch guidewire into both the left anterior descending artery and diagonal branch and predilated the stenosis in the left anterior descending artery with a 2.5 mm diameter by 15 mm long compliant balloon, resulting in further compromise of the lumen of the diagonal artery (Figures 28-2, 28-3 and Video 28-2). Balloon dilation of the diagonal was performed, and during the catheter manipulations, the operator noted that the tip of the diagonal wire appeared to have migrated either into a small branch or outside of the lumen of the diagonal artery (Figure 28-4). The wire was repositioned and angiography demonstrated contrast staining emanating from the diagonal branch consistent with a wire perforation (Figure 28-5 and Video 28-3). The patient remained asymptomatic and hemodynamically stable with no evidence of tamponade. The operator continued the eptifibatide infusion after repeat angiography 5 minutes later showed persistent contrast staining but no evidence of active bleeding from the site. The “crush stent” procedure was performed with a 3.0 mm diameter by 18 mm long sirolimus-eluting stent placed in the left anterior descending artery and a 2.25 mm diameter by 12 mm long bare-metal stent placed in the diagonal branch (Figure 28-6). The final angiographic appearance was excellent with no evidence of additional contrast extravasation from the wire perforation site (Figure 28-7 and Video 28-4). The obtuse marginal lesion was then treated with another drug-eluting stent without complication.

Postprocedural course

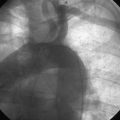

His postprocedural course was uncomplicated. After overnight observation, he was discharged on metoprolol, atorvastatin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. He remained free of angina 1 year later. Interestingly, he developed recurrent angina nearly 3 years later and was found to have progressive disease in the right coronary artery; however, the stents placed in the left anterior descending and diagonal arteries remained widely patent (Figure 28-8).

Discussion

Perforation of the coronary artery is a potentially deadly complication of coronary intervention.1 The clinical consequences range from a benign angiographic finding to dramatic cardiovascular collapse from tamponade caused by frank bleeding into the pericardial space from a large tear in the artery. The perforation shown in the case presented here was caused by the 0.014 inch guidewire and is an example of the benign side of the spectrum of coronary perforation.

In the event of free contrast extravasation and tamponade, management of a guidewire perforation is similar to that caused by other mechanisms. Depending on the patient’s clinical status, management may include pericardiocentesis, cessation and reversal of procedural anticoagulants, and immediate balloon inflation in the vessel proximal to the perforation site. Prolonged balloon inflation (10 to 20 minutes) may be required to staunch bleeding while efforts are taken to correct the procedural coagulopathy. The PTFE-covered stents do not have a role since the site of perforation is distal and not amenable to this strategy.2,3 Rarely, surgery is necessary for guidewire perforations; this is more likely in the presence of a chronic occlusion with perforation from unsuccessful attempts at crossing the occlusion with a guidewire. In this situation, there may be back-bleeding from collaterals or the operator may find it difficult or impossible to inflate a balloon proximal to the perforation without distal wire access.

1 Fasseas P., Orford J.L., Panetta C.J., et al. Incidence, correlates, management and clinical outcome of coronary perforation: Analysis of 16,298 procedures. Am Heart J. 2004;147:140-145.

2 Briguori C., Nishida T., Anzuini A., DiMario C., Grube E., Colombo A. Emergency polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent implantation to treat coronary ruptures. Circulation. 2000;102:3028-3031.

3 Lansky A.J., Yank Y., Khan Y., Costa R.A., Pietras C., Tsuchiya Y., Cristea E., Collins M., Mehran R., Dangas G.D., Moses J.W., Leon M.B., Stone G.W. Treatment of coronary artery perforations complicating percutaneous coronary intervention with a polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent graft. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:370-374.