CHAPTER 26

Radial Neuropathy

Definition

The radial nerve originates from the C5 to T1 roots. These nerve fibers travel along the upper, middle, and lower trunks. They continue as the posterior cord and terminate as the radial nerve.

The radial nerve is prone to entrapment in the axilla (crutch palsy), the upper arm (spiral groove), the forearm (posterior interosseous nerve), and the wrist (cheiralgia paresthetica). Radial neuropathies can result from direct nerve trauma, compressive neuropathies, neuritis, or complex humerus fractures [1].

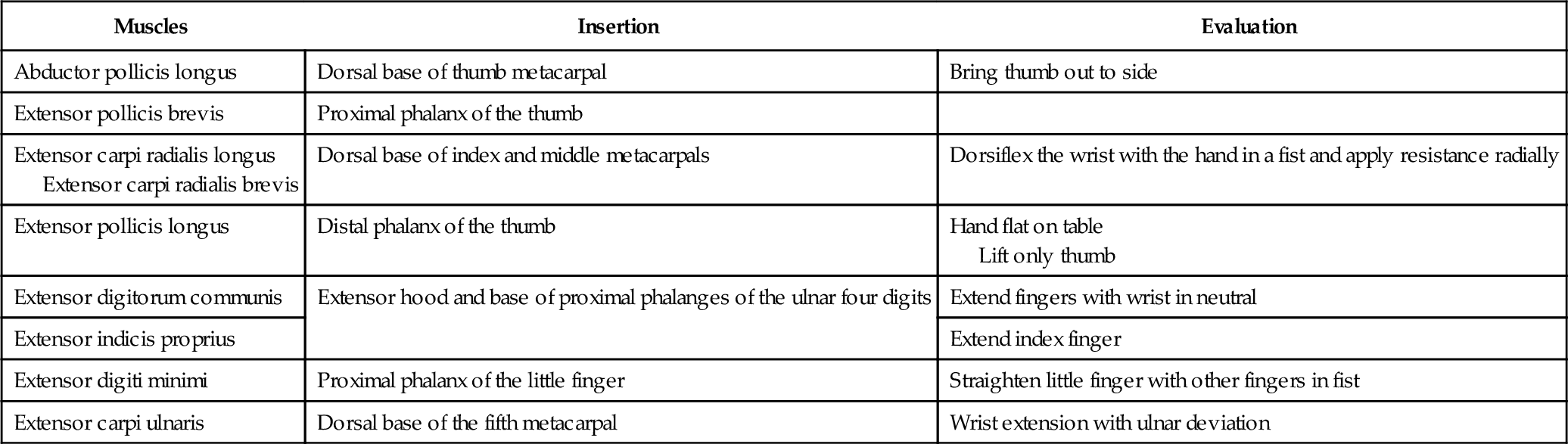

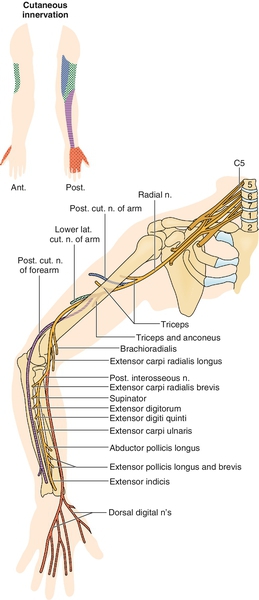

In the proximal arm, the radial nerve gives off three sensory branches (posterior cutaneous nerve of the arm, lower lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm, and posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm). The radial nerve supplies a motor branch to the triceps and anconeus before wrapping around the humerus in the spiral groove, a common site of radial nerve injury. The nerve then supplies motor branches to the brachioradialis, the long head of the extensor carpi radialis, and the supinator. Just distal to the lateral epicondyle, the radial nerve divides into the posterior interosseous nerve (a motor nerve) and the superficial sensory nerve (a sensory nerve). The posterior interosseous nerve supplies the supinator muscle and then travels under the arcade of Frohse (another potential site of compression) before coursing distally to supply the extensor digitorum communis, extensor digiti minimi, extensor carpi ulnaris, abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, and extensor indicis proprius. The superficial sensory nerve supplies sensations to the dorsum of the hand, excluding the fifth and ulnar half of the fourth digit, which is supplied by the ulnar nerve (Fig. 26.1). Radial neuropathy is relatively uncommon compared with other compressive neuropathies of the upper limb. A study in 2000 showed that the annual age-standardized rates per 100,000 of new presentations in primary care were 2.97 in men and 1.42 in women for radial neuropathy, 87.8 in men and 192.8 in women for carpal tunnel syndrome, and 25.2 in men and 18.9 in women for ulnar neuropathy [2].

Symptoms

Symptoms of radial neuropathy depend on the site of nerve entrapment [3] (Table 26.1). In the axilla, the entire radial nerve can be affected. This may be seen in crutch palsy if the patient is improperly using crutches in the axilla, causing compression. With this type of injury, the median, axillary, or suprascapular nerves may also be affected. All radially innervated muscles (including the triceps) as well as sensation in the posterior arm, forearm, and dorsum of the hand may be affected.

The radial nerve is especially prone to injury in the spiral groove (also known as Saturday night palsy or honeymooner’s palsy). Symptoms include weakness of all radially innervated muscles except the triceps and sensory changes in the posterior arm and hand. In the forearm, the radial nerve is susceptible to injury as it passes through the supinator muscle and the arcade of Frohse. Because the superficial radial sensory nerve branches before this area of impingement, sensation will be spared. The patient will complain of weakness in the wrist and finger extensors. On occasion, the superficial radial sensory nerve is entrapped at the wrist, usually as a result of lacerations at the wrist or a wristwatch that is too tight. In this situation, the symptoms will be sensory, involving the dorsum of the hand.

Physical Examination

The findings on physical examination depend on where the injury is along the anatomic course of the nerve. A Tinel sign may be present at the site of compression. Injury in the axilla will lead to weakness in elbow extension, wrist extension, and finger extension. The entire sensory distribution of the radial nerve will be affected. If the injury is in the spiral groove, the examination findings will be the same, except that triceps function will be spared. Radial neuropathy in the forearm will usually result in sparing of sensory functions. If the nerve is entrapped in the supinator muscle, supinator strength should be normal. This is because the branch to innervate the supinator muscle is given off proximal to the muscle. The patient will have radial deviation with wrist extension and weakness of finger extensors. Injury to the superficial radial sensory nerve will result in paresthesias or dysesthesias over the radial sensory distribution in the hand.

Functional Limitations

The prognosis for patients with acute compressive radial neuropathies is good [4]. Functional limitation depends on the extent of the injury and the level of the lesion. In high radial nerve palsy, wrist and finger extension are impaired. However, the inability to stabilize the wrist in extension leads to the main functional limitation. The loss of the power of the wrist and finger extensors destroys the essential reciprocal tenodesis action vital to the normal grasp and release pattern of the hand and results in ineffective finger flexion function. Activities such as gripping or holding objects will therefore be impaired. The sensory loss associated with radial nerve palsy is of lesser functional consequence compared with that of median or ulnar nerve lesions. Sensory loss is limited to the dorsoradial aspect of the hand, and this leaves the more functionally important palmar surface intact. Pain from posterior interosseous nerve entrapment can be disabling enough to limit the function of the involved extremity.

Diagnostic Studies

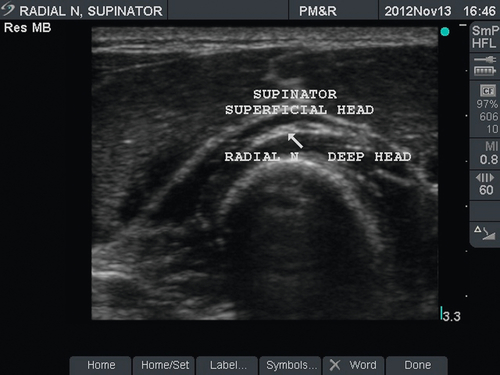

Electrodiagnostic testing (electromyography and nerve conduction studies) is the most useful test to assess for radial neuropathies. This test can be used to diagnose, to localize, to prognosticate, and to rule out other nerve injuries. The test is usually performed 3 weeks after the onset of clinical findings [5]. At this time, muscle denervation potentials will be observed if axonal injury is present. Radiography and magnetic resonance imaging can be used to rule out a mass (ganglion or tumor) [6] or fracture [7,8] as the reason for the radial neuropathy. Studies have used ultrasound (Fig. 26.2) to investigate the appearance of the radial nerve in the lateral aspect of the distal upper arm [9–11].

Treatment

Initial

Radial neuropathies from compression can be managed conservatively in nearly all cases. Elimination of offending factors, such as improper use of crutches, and avoidance of provocative activities are the first steps in the treatment of radial neuropathy. Medications, including tricyclic agents, anticonvulsants, antiarrhythmics, topical solutions, clonidine, and opioids, can be considered for pain management. Nonpharmaceutical treatments, including transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and acupuncture, may be considered as adjuvants to medication [12].

Rehabilitation

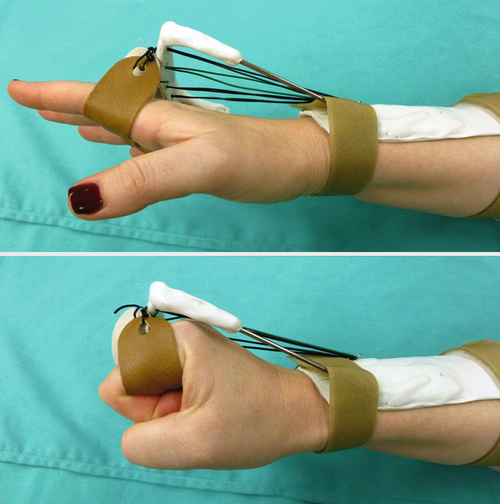

The main goal of rehabilitation is prevention of joint contractures, shortening of the flexor tendons, and overstretching of the extensors while waiting for nerve recovery. This can be achieved by exercises to maintain range of motion, passive stretching, and proper splinting. Functional splinting can make relatively normal use of the hand possible. Dynamic splints use elastic to passively extend the finger at the metacarpophalangeal joints with the wrist immobilized in slight dorsiflexion. This provides stability to the wrist joint, passive extension of the digits by the elastic band, and active flexion of the fingers. A splint designed at the Hand Rehabilitation Center in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, uses a static nylon cord rather than a dynamic rubber band to suspend the proximal phalanges (Fig. 26.3). The design simulates the tenodesis action of the normal grasp and release pattern of the hand.

Postsurgical release of compression should be immediately followed by exercises to increase or to maintain range of motion and a nerve gliding program to prevent adhesions. Overly aggressive strengthening should be avoided during reinnervation. In tendon transfers, preoperative strengthening of the muscle to be transferred and postoperative muscle reeducation are vital to the success of the procedure.

Procedures

Local anesthetic blocks or injections of hydrocortisone can be used [16] but are rarely necessary and have shown only temporary symptomatic relief. Lateral epicondylitis may mimic posterior interosseous nerve entrapment at the elbow. When lateral epicondylitis does not respond to conservative treatment, including injections of the lateral epicondyle, a diagnostic and therapeutic radial nerve injection at the elbow may be indicated [17].

Surgery

Surgical decompression may be required for patients who do not respond to conservative treatment or patients with severe nerve injury. Radial tunnel release has been advocated for compression neuropathies of the posterior interosseous nerve, but the results have been questionable [18]. Surgical intervention for anastomosis may be indicated in cases of complete radial injury (neurotmesis). Tendon transfers may be considered in these instances if the surgery is not performed or is not successful [19,20]. Care must be exercised to avoid the radial sensory branch during operations involving the wrist [16]. Surgery has been noted to be less successful if there are coexisting additional nerve compressions or lateral epicondylitis or if the patient is receiving workers’ compensation [21].

Potential Disease Complications

Patients with incomplete recovery may suffer significant functional loss in the upper extremity. Like any patient with nerve injury, they are at risk for development of complex regional pain syndrome (reflex sympathetic dystrophy) [22]. Contractures and chronic pain may develop as well.

Potential Treatment Complications

There are inherent risks with any surgery, including failure to correct the problem, infection, additional deformity, and death. Any injection or surgery involving the wrist should avoid the superficial radial sensory nerve as this could cause additional paresthesias or dysesthesias.