CHAPTER 25

Olecranon Bursitis

Definition

Olecranon bursitis is a swelling of the subcutaneous, synovium-lined sac that overlies the olecranon process. The bursa functions to cushion the tip of the olecranon and to reduce friction between the olecranon and the overlying skin during elbow motion. Because of the paucity of soft tissue covering the elbow, the olecranon bursa is susceptible to injury.

The causes of olecranon bursitis can be classified as traumatic, inflammatory, septic, and idiopathic [1]. Traumatic bursitis may result from a single, direct blow to the elbow or from repetitive stress. Football players, particularly those who play on artificial turf, are at risk for development of acute bursitis. More commonly, repeated minor trauma from direct pressure on the elbow or elbow motion is responsible for the problem. Trauma is thought to stimulate increased vascularity, resulting in bursal fluid production and fibrin coating of the bursal wall [2]. Persons engaged in certain occupations or certain activities are susceptible to olecranon bursitis, including auto mechanics, gardeners, plumbers, carpet layers, students, gymnasts, wrestlers, and dart throwers. Interestingly, approximately 7% of hemodialysis patients develop olecranon bursitis [3]. Repeated, prolonged positioning of the elbow and anticoagulation appear to be contributing factors.

Inflammatory causes include diseases that affect the bursa primarily, such as rheumatoid arthritis, gout, and chondrocalcinosis. Olecranon bursitis is commonly seen in rheumatoid patients, in whom the bursa may actually communicate with the affected elbow joint. Crystal-induced olecranon bursitis may be difficult to differentiate from septic bursitis.

Septic olecranon bursitis represents 20% of olecranon bursitis [4]. The source is most often transcutaneous, and about half have identifiable breaks in the skin. When culture samples are positive, the bursal fluid usually contains Staphylococcus aureus [5]. Sepsis is unusual. Both underlying bursal disease (gout, rheumatoid arthritis, chondrocalcinosis) and systemic conditions such as diabetes mellitus, uremia, alcoholism, injection drug use, and steroid therapy are considered predisposing factors. There appears to be a seasonal trend, with a peak of staphylococcal septic bursitis during the summer months [6].

In approximately 25% of cases, no identifiable cause of the olecranon bursitis is found. Presumably, repetitive, minor irritation is responsible for the bursal swelling.

Symptoms

Painless swelling is the chief complaint in noninflammatory, aseptic olecranon bursitis. When patients are symptomatic, they usually have discomfort when the elbow is flexed beyond 90 degrees and have trouble resting on the elbow. Moderate to severe pain is the predominant complaint of patients with septic or crystal-induced olecranon bursitis. These patients may also have fever, malaise, and limited elbow motion.

Physical Examination

The physical examination varies somewhat, depending on the underlying condition. With noninflammatory aseptic bursitis, a nontender fluctuant mass is present over the tip of the elbow (Fig. 25.1). Elbow motion is usually full and painless. With chronic bursitis, the fluctuance may be replaced with a thickened bursa (Fig. 25.2).

The distinction between crystal-induced and septic bursitis may be subtle. Both conditions may produce tender fluctuance, induration, swelling, warmth, and local erythema. Elbow flexion may be somewhat limited, although not as limited as with septic arthritis of the elbow joint. Fever and a break in the skin over the elbow are important clues to an underlying septic process (Fig. 25.3). Cellulitis extending distally along the forearm is also more likely to be due to an infection.

In inflammatory cases, pain inhibition may produce mild weakness of elbow flexion and extension. Sensation and distal pulses are unaffected. Examination findings of other joints should also be normal.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations depend on the underlying diagnosis. Traumatic olecranon bursitis usually causes minimal functional limitation. Patients may note some mild discomfort with direct pressure over the tip of the elbow (e.g., when sitting at a desk or resting the arm on the armrest of a chair or in the car). With crystal-induced and septic bursitis, pain is the predominant issue. Patients may have trouble sleeping and have difficulty with most activities of daily living that involve the affected extremity (e.g., dressing, grooming, cleaning, shopping, and carrying packages).

Diagnostic Studies

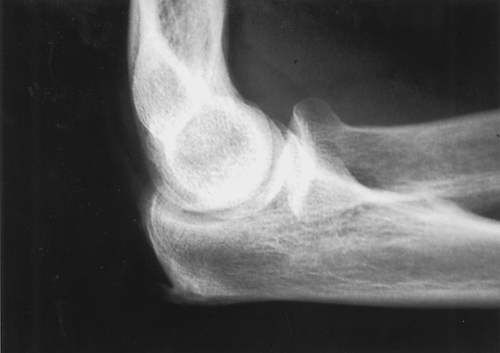

The diagnosis of aseptic, noninflammatory olecranon bursitis is usually straightforward, based on a characteristic appearance on physical examination. In this setting, additional studies are not usually necessary. However, plain radiographs may demonstrate an olecranon spur in about one third of cases (Fig. 25.4). Because this is an extra-articular process, a joint effusion is not present.

If crystal-induced or septic bursitis is suspected, aspiration of the bursal fluid is usually indicated. The fluid should be sent for cell count, Gram stain and culture, and crystal analysis. Acute, traumatic bursal fluid typically has a serosanguineous appearance, containing fewer than 1000 white blood cells per high-power field, with a predominance of monocytes. Infected bursal fluid usually contains an increased white blood cell count, with a high percentage of polymorphonuclear cells. The Gram stain is positive in only 50% of septic cases. Even in the setting of infection, the fluid should be examined under a polarizing microscope because simultaneous infectious and crystal-induced arthritis can occur [7].

A complete blood cell count and determination of serum uric acid level may provide supportive information in confusing cases, although a normal serum white blood cell count does not preclude septic bursitis.

Magnetic resonance imaging may be of some value to distinguish septic from nonseptic olecranon bursitis, although there is considerable overlap of findings [8]. Absence of bursal and soft tissue enhancement is consistent with nonseptic olecranon bursitis. Olecranon marrow edema is suggestive but not diagnostic of septic olecranon bursitis. The use of magnetic resonance imaging may also help clarify the diagnosis of unusual masses around the elbow.

Treatment

Initial

Treatment of traumatic olecranon bursitis begins with prevention of further injury to the involved elbow. An elastic elbow pad provides compression and protects the bursa. The patient should be counseled in ways of protecting the elbow at work and during recreation. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are usually prescribed. Traumatic, noninflammatory bursitis usually resolves with this treatment [9]. On occasion, when the bursa is very large, aspiration of the bloody fluid will be a first-line treatment. This is followed by application of a compressive wrap and splint for several days.

In suspected cases of septic olecranon bursitis, it is important to palpate for fluctuance. If a fluid collection is appreciated, the bursa should be aspirated (see the section on procedures). When cellulitis over the tip of the elbow is present without an obvious collection, empirical treatment with antibiotic therapy to cover penicillin-resistant S. aureus, the most common offender, is recommended. (Less common organisms include group A streptococcus and Staphylococcus epidermidis.) The decision whether to use oral or intravenous antibiotics depends on the appearance of the elbow, the signs of systemic illness, and the general health of the patient. The elbow should be splinted in a semiflexed position (approximately 60 degrees) without pressure on the olecranon. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be prescribed unless they are contraindicated for empirical treatment of gout and pseudogout. When final culture results return, the antibiotic therapy is adjusted appropriately. Outpatient cases are observed closely, with any changes in the size of the bursa and the quality of the overlying skin noted; oral antibiotic therapy should continue for at least 10 days.

Patients with extensive infection or underlying bursal disease, systemic disease, or immunosuppression and outpatients refractory to oral treatment should be treated with an intravenous cephalosporin. In one study, the average duration of intravenous therapy was 4.4 days if symptoms had been present for less than 1 week and 9.2 days if symptoms had been present for longer than 1 week [10]. The conversion to oral antibiotics should occur only after consistent improvement is seen in the appearance of the patient and the elbow. Serial aspirations may also constitute part of the therapy; alternatively, some clinicians use a suction irrigation system placed into the bursa. Surgical consultation is recommended if the bursitis has failed to improve within several days of appropriate management.

Rehabilitation

Because the process is extra-articular, permanent elbow stiffness is not usually a problem. Physical or occupational therapy for gentle range of motion may be indicated once the olecranon wound has clearly healed. Extreme flexion should be avoided early on because this position puts tension on the already compromised skin. If prolonged immobilization is necessary to permit the soft tissues to heal, therapy may include range of motion and strengthening of the arm and forearm.

Patients who have traumatic or recurrent olecranon bursitis should be counseled in ways to modify their home and work activities to eliminate irritation to the bursa. This might include the use of ergonomic equipment, such as forearm rests (also called data arms) that do not contact the elbow. In some instances, vocational retraining may be indicated.

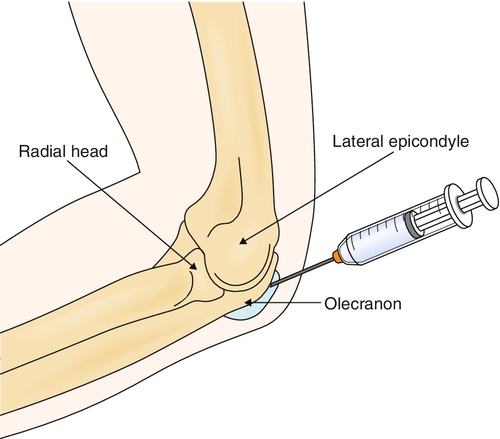

Procedures

Needle aspiration is therapeutic as well as diagnostic and usually reduces symptoms (Fig. 25.5). It can be performed for patients with traumatic bursitis if they have symptoms compromising their regular activities and should be done (as previously described) for patients in whom inflammatory or septic causes are suspected.

The elbow is prepared in a sterile fashion. The skin is infiltrated locally with 1% lidocaine (Xylocaine). To minimize the risk of persistent drainage after aspiration, it is recommended to insert a long 18-gauge needle at a point well proximal to the tip of the elbow. The bursa should be drained as completely as possible. The fluid should be sent for Gram stain, culture and sensitivity, cell count, and crystal analysis.

Postinjection care includes local icing for 10 to 20 minutes. A sterile compressive dressing is then applied, followed by an anterior plaster splint that maintains the elbow in 60 degrees of flexion.

Corticosteroid injections into the bursa have been shown to hasten the resolution of traumatic and crystal-induced olecranon bursitis [11]. However, the risk of complications is high, including infection, skin atrophy, and chronic local pain. Consequently, the routine use of steroid injections for olecranon bursitis is not recommended.

Surgery

Surgery is rarely indicated for traumatic olecranon bursitis. Chronic drainage of bursal fluid is the most common indication for surgery [1]. Bursectomy is conventionally done through an open technique, although a recently developed arthroscopic method has shown some promise. Surgery is usually curative for both traumatic and septic bursitis. However, the success rates are very different for patients with rheumatoid arthritis; surgery provides successful relief for 5 years in only 40% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis versus 94% of nonrheumatoid patients [12].

After surgery, suction drains are often placed for several days. Splinting of the elbow at 60 degrees of flexion or greater for 2 weeks is thought to help prevent recurrence.

Potential Disease Complications

Septic bursitis poses the greatest threat with regard to disease complications. If it is neglected, the infection may thin the overlying skin and eventually erode through it (Fig. 25.6). This complication is difficult to manage, often requiring extensive débridement and flap coverage. Persistent infection can also result in osteomyelitis of the olecranon process. Immunocompromised patients are at risk for sepsis from olecranon bursitis. Necrotizing fasciitis originating from a septic olecranon bursitis, although rare, may prove to be fatal.

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects on the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Persistent drainage from a synovial fistula is an uncommon complication of aspiration of the olecranon bursa; however, this problem is serious enough to discourage the routine aspiration of olecranon bursal fluid in noninflammatory conditions. Complications of steroid injection, as described earlier, can be serious. In addition, wound problems are the major complication associated with surgical treatment of olecranon bursitis. Because of the superficial location of the olecranon and the tenuous blood supply of the overlying skin, wound healing can be difficult. Malnourished and chronically ill patients are especially at risk for surgical complications.